| Revision as of 05:17, 24 December 2018 editCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,406,217 editsm Add: pmc, pages, issue, volume. Removed parameters. Formatted dashes. You can use this bot yourself. Report bugs here. | User-activated.← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:56, 7 February 2019 edit undoKryptokromulous (talk | contribs)35 edits The strong statement that there was no support for the efficacy and safety of psychobiotics in humans was plainly false and it was corrected using an additional source as reference.Tag: Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{medref|date=December 2018}} | {{medref|date=December 2018}} | ||

| '''Psychobiotics''' is a term used in preliminary research to refer to ] that, when ingested in appropriate amounts, might confer a ] benefit by affecting ] of the host organism.<ref name=":0" /> Under research is whether bacteria might play a role in the ]. |

'''Psychobiotics''' is a term used in preliminary research to refer to ] that, when ingested in appropriate amounts, might confer a ] benefit by affecting ] of the host organism.<ref name=":0" /> Under research is whether bacteria might play a role in the ]. However, as of 2018, there is a paucity of ] testing the effects of live, ingested bacterial strains on clear mental health outcomes, and those that have been done provide inconclusive results when viewed in aggregate.<ref name="romijn">{{cite journal | vauthors = Romijn AR, Rucklidge JJ | title = Systematic review of evidence to support the theory of psychobiotics | journal = Nutrition Reviews | volume = 73 | issue = 10 | pages = 675–93 | date = October 2015 | pmid = 26370263 | doi = 10.1093/nutrit/nuv025 | url = https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article/73/10/675/1848054 }}</ref><ref name="lin">{{cite journal | vauthors = Liu B, He Y, Wang M, Liu J, Ju Y, Zhang Y, Liu T, Li L, Li Q | title = Efficacy of probiotics on anxiety-A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials | journal = Depression and Anxiety | volume = 35 | issue = 10 | pages = 935–945 | date = July 2018 | pmid = 29995348 | doi = 10.1002/da.22811}}</ref> | ||

| == Types == | == Types == | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| == Research == | == Research == | ||

| The field of psychobiotics in humans is nascent, though there have been many studies in rodents demonstrating increased cognitive functioning, decreased anxiety, and decreases in stress related pathology.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Burnet|first=Philip W. J.|last2=Cryan|first2=John F.|last3=Dinan|first3=Timothy G.|last4=Harty|first4=Siobhán|last5=Lehto|first5=Soili M.|last6=Sarkar|first6=Amar|date=2016-11-01|title=Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria–Gut–Brain Signals|url=https://www.cell.com/trends/neurosciences/abstract/S0166-2236(16)30113-8|journal=Trends in Neurosciences|language=English|volume=39|issue=11|pages=763–781|doi=10.1016/j.tins.2016.09.002|issn=0166-2236|pmc=PMC5102282|pmid=27793434}}</ref> However, the human literature has yet to catch up with most rodent experiments, and has so far failed to produce a high number of well designed, randomized trials. Several recent reviews have highlighted the fact that there is a need for more diverse human studies, particularly because those that exist are often hard to compare and have contradictory outcomes.<ref name=romijn/><ref name=lin/> | |||

| As of 2018, there had been several clinical trials of psychobiotics; reviews of these trials concluded that there is no good evidence that psychobiotics are safe and effective in humans.<ref name=romijn/><ref name=lin/> | |||

| ===Species=== | ===Species=== | ||

Revision as of 06:56, 7 February 2019

| This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. Please review the contents of the article and add the appropriate references if you can. Unsourced or poorly sourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Psychobiotic" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2018) |  |

Psychobiotics is a term used in preliminary research to refer to live bacteria that, when ingested in appropriate amounts, might confer a mental health benefit by affecting microbiota of the host organism. Under research is whether bacteria might play a role in the gut-brain axis. However, as of 2018, there is a paucity of randomized controlled trials testing the effects of live, ingested bacterial strains on clear mental health outcomes, and those that have been done provide inconclusive results when viewed in aggregate.

Types

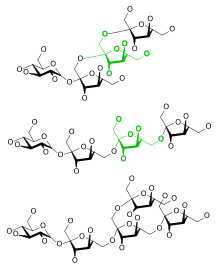

In experimental probiotic psychobiotics, the bacteria most commonly used are gram-positive bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus families, as these do not contain lipopolysaccharide chains, reducing the likelihood of an immunological response. Prebiotics are substances, such as fructans and oligosaccharides, that induce the growth or activity of beneficial microorganisms, such as bacteria on being fermented in the gut. Multiple bacterial species contained in a single probiotic broth is known as a polybiotic.

Research

The field of psychobiotics in humans is nascent, though there have been many studies in rodents demonstrating increased cognitive functioning, decreased anxiety, and decreases in stress related pathology. However, the human literature has yet to catch up with most rodent experiments, and has so far failed to produce a high number of well designed, randomized trials. Several recent reviews have highlighted the fact that there is a need for more diverse human studies, particularly because those that exist are often hard to compare and have contradictory outcomes.

Species

Several species of bacteria have been used in probiotic psychobiotic research:

- Lactobacillus helveticus

- Bifidobacterium longum

- Lactobacillus casei

- Lactobacillus plantarum

- Lactobacillus acidophilus

- Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus

- Bifidobacterium breve

- Bifidobacterium infantis

- Streptococcus salivarius

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus

- Lactobacillus gasseri

References

- ^ Sarkar A, Lehto SM, Harty S, Dinan TG, Cryan JF, Burnet PW (November 2016). "Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria-Gut-Brain Signals". Trends in Neurosciences. 39 (11): 763–781. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.09.002. PMC 5102282. PMID 27793434.

- ^ Romijn AR, Rucklidge JJ (October 2015). "Systematic review of evidence to support the theory of psychobiotics". Nutrition Reviews. 73 (10): 675–93. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv025. PMID 26370263.

- ^ Liu B, He Y, Wang M, Liu J, Ju Y, Zhang Y, Liu T, Li L, Li Q (July 2018). "Efficacy of probiotics on anxiety-A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Depression and Anxiety. 35 (10): 935–945. doi:10.1002/da.22811. PMID 29995348.

- Hutkins RW; Krumbeck JA; Bindels LB; Cani PD; Fahey G Jr.; Goh YJ; Hamaker B; Martens EC; Mills DA; Rastal RA; Vaughan E; Sanders ME (2016). "Prebiotics: why definitions matter". Curr Opin Biotechnol. 37: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2015.09.001. PMC 4744122. PMID 26431716.

- ^ Bambury A, Sandhu K, Cryan JF, Dinan TG (December 2017). "Finding the needle in the haystack: systematic identification of psychobiotics". British Journal of Pharmacology. 175 (24): 4430–4438. doi:10.1111/bph.14127. PMC 6255950. PMID 29243233.

- Burnet, Philip W. J.; Cryan, John F.; Dinan, Timothy G.; Harty, Siobhán; Lehto, Soili M.; Sarkar, Amar (2016-11-01). "Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria–Gut–Brain Signals". Trends in Neurosciences. 39 (11): 763–781. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.09.002. ISSN 0166-2236. PMC 5102282. PMID 27793434.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - Dinan, Timothy; Stanton, Catherine; Cryan, John (November 2013). "Psychobiotics: A Novel Class of Psychotropic". Biological Psychiatry. 74: 720–726.