| Revision as of 00:29, 8 April 2019 editHopsonRoad (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users31,038 edits →Relationship between true and magnetic direction: Remove heading. Resize image. Give legend in caption.← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:41, 8 April 2019 edit undoHopsonRoad (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users31,038 edits Remove unsourced, redundant material. Move, resize images.Next edit → | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| == Course, track, route and heading == | == Course, track, route and heading == | ||

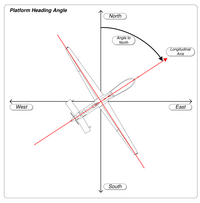

| ⚫ | {{multiple image | ||

| ⚫ | The path that a vessel follows over the ground is called a ], ''course made good'' or ''course over the ground''.<ref name="Bartlett" /> For an aircraft it is simply its ''track''.<ref name=":0" /> The intended track is a ''route''. For ships and aircraft, routes are typically ] segments between ]. A navigator determines the ''bearing'' (the compass direction from the craft's current position) of the next waypoint. Because water currents or wind can cause a craft to drift off course, a navigator sets a ''course to steer'' that compensates for drift. The helmsman or pilot points the craft on a ''heading'' that corresponds to the course to steer. If the predicted drift is correct, then the craft's track will correspond to the planned course to the next waypoint.<ref name="Bartlett" /><ref name=":0" /> Course directions are specified in degrees from north, either true or magnetic. In ], north is usually expressed as 360°.<ref name="Nolan2010">{{cite book|author=Michael Nolan|title=Fundamentals of Air Traffic Control|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6yhTiGC3ulcC&pg=PA201|date=28 January 2010|publisher=Cengage Learning|isbn=1-4354-8272-7|page=201|quote=For example, a runway heading north would have a magnetic heading of 360°.}}</ref> Navigators used ] instead of compass degrees, e.g. "northeast" instead of 45° until the 20th century. | ||

| ⚫ | | width1 = 200 | ||

| ⚫ | | footer = True heading (left) and magnetic heading (right) | ||

| ⚫ | | image1 = MISB ST 0601.8 - Platform Heading Angle.png | ||

| ⚫ | | alt1 = | ||

| ⚫ | | width2 = 200 | ||

| ⚫ | | image2 = MISB ST 0601.8 - Platform Magnetic Heading.png | ||

| ⚫ | | alt2 = | ||

| ⚫ | | caption2 = | ||

| ⚫ | }} | ||

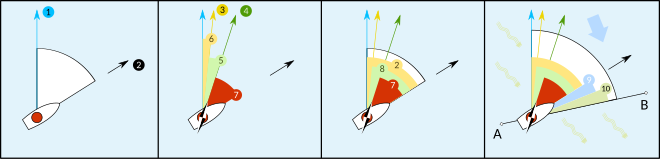

| [[Image:Course (navigation).svg|thumb|upright=3|Heading and track (A to B)<br> | [[Image:Course (navigation).svg|thumb|upright=3|Heading and track (A to B)<br> | ||

| 1 - True North | 1 - True North | ||

| Line 31: | Line 39: | ||

| 9, 10 - Effects of crosswind and tidal current, causing the vessel's track to differ from its heading. | 9, 10 - Effects of crosswind and tidal current, causing the vessel's track to differ from its heading. | ||

| A, B - Vessel's track.]] | A, B - Vessel's track.]] | ||

| ⚫ | The path that a vessel follows over the ground is called a ], ''course made good'' or ''course over the ground''.<ref name="Bartlett" /> For an aircraft it is simply its ''track''.<ref name=":0" /> The intended track is a ''route''. For ships and aircraft, routes are typically ] segments between ]. A navigator determines the ''bearing'' (the compass direction from the craft's current position) of the next waypoint. Because water currents or wind can cause a craft to drift off course, a navigator sets a ''course to steer'' that compensates for drift. The helmsman or pilot points the craft on a ''heading'' that corresponds to the course to steer. If the predicted drift is correct, then the craft's track will correspond to the planned course to the next waypoint.<ref name="Bartlett" /><ref name=":0" /> Course directions are specified in degrees from north, either true or magnetic. In ], north is usually expressed as 360°.<ref name="Nolan2010">{{cite book|author=Michael Nolan|title=Fundamentals of Air Traffic Control|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6yhTiGC3ulcC&pg=PA201|date=28 January 2010|publisher=Cengage Learning|isbn=1-4354-8272-7|page=201|quote=For example, a runway heading north would have a magnetic heading of 360°.}}</ref> Navigators used ] instead of compass degrees, e.g. "northeast" instead of 45° until the 20th century. | ||

| ==Aircraft heading== | |||

| ⚫ | {{multiple image | ||

| ⚫ | | width1 = |

||

| ⚫ | | footer = True heading (left) and magnetic heading (right) | ||

| ⚫ | | image1 = MISB ST 0601.8 - Platform Heading Angle.png | ||

| ⚫ | | alt1 = | ||

| ⚫ | | width2 = |

||

| ⚫ | | image2 = MISB ST 0601.8 - Platform Magnetic Heading.png | ||

| ⚫ | | alt2 = | ||

| ⚫ | | caption2 = | ||

| ⚫ | }} | ||

| An '''aircraft's heading''' is the direction that the aircraft's nose is pointing. | |||

| It is referenced by using either the ] or ], two instruments that most aircraft have as standard. Using standard instrumentation, it is in reference to the local magnetic north direction. True heading is in relation to the lines of meridian (north–south lines). The units are degrees from north in a clockwise direction. North is 0°, east is 90°, south is 180°, and west is 270°. | |||

| Note that, due to wind forces, the direction of movement of the aircraft, or track, is not the same as the heading. The nose of the aircraft may be pointing due west, for example, but a strong northerly wind will change its track south of west. The angle between heading and track is known as the drift angle. Crab angle is the amount of correction an aircraft must be turned into the wind in order to maintain the desired course. It is opposite in direction to the drift angle and approximately equal in magnitude for small angles. | |||

| An aircraft can have instruments on board that show to the pilot the aircraft heading. The ] can be programmed to maintain either the aircraft heading or its course (when set in a proper mode and with correct navigational data inputs). | |||

| == Relationship between course and heading == | |||

| The difference between the course and heading, known as the ''drift'', is due to the motion of the conveying medium, water for a vessel or air for an aircraft, plus other effects like skidding or slipping. The drift can be determined by the adding the vectors of velocity for the vessel or aircraft and the velocity over the ground of the medium in which it is traveling (water or air). For a vessel, one uses published or observed figures for ocean or river currents. For an aircraft, this is determined by the ]. | |||

| The ''heading'' will differ from the ''course'' depending on (1) the forward speed (speed parallel to the ''heading'') of the vehicle in its medium (air for an aircraft, water for a vessel), (2) drift speed (speed ] to the ''heading'') in its medium (only for vessels, especially for ]s at close ]), and (3) wind speed and wind direction (only for aircraft) or current speed and current direction (only for vessels). In the event of a ] or ], ''heading'' and course in an aircraft are the same. For a ship at sea, if a current is running parallel to the ''heading'', then the ''course'' is the same as the ''heading''. | |||

| In an aircraft, to correct for the difference between ''heading'' and ''course'', a navigator uses the ]. In the early days of navigation, wind speed was estimated by the drift observed and the plane was steered to correct for the wind influence. Contemporary navigational aids have simplified the problem of determining course to steer. | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

Revision as of 00:41, 8 April 2019

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Course" navigation – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In navigation, the course of a vessel or aircraft is the cardinal direction in which the craft is to be steered. The course is to be distinguished from the heading, which is the compass direction in which the craft's bow or nose is pointed.

Course, track, route and heading

True heading (left) and magnetic heading (right)

True heading (left) and magnetic heading (right)

1 - True North 2 - Heading, the direction the vessel is "pointing towards" 3 - Magnetic north, which differs from true north by the magnetic variation. 4 - Compass north, including a two-part error; the magnetic varation (6) and the ship's own magnetic field (5) 5 - Magnetic deviation, caused by vessel's magnetic field. 6 - Magnetic variation, caused by variations in earth's magnetic field. 7 - Compass heading or compass course, before correction for magnetic deviation or magnetic variation. 8 - Magnetic heading, the compass heading corrected for magnetic deviation but not magnetic variation; thus, the heading reliative to magnetic north. 9, 10 - Effects of crosswind and tidal current, causing the vessel's track to differ from its heading. A, B - Vessel's track.

The path that a vessel follows over the ground is called a ground track, course made good or course over the ground. For an aircraft it is simply its track. The intended track is a route. For ships and aircraft, routes are typically straight-line segments between waypoints. A navigator determines the bearing (the compass direction from the craft's current position) of the next waypoint. Because water currents or wind can cause a craft to drift off course, a navigator sets a course to steer that compensates for drift. The helmsman or pilot points the craft on a heading that corresponds to the course to steer. If the predicted drift is correct, then the craft's track will correspond to the planned course to the next waypoint. Course directions are specified in degrees from north, either true or magnetic. In aviation, north is usually expressed as 360°. Navigators used ordinal directions, instead of compass degrees, e.g. "northeast" instead of 45° until the 20th century.

See also

- Acronyms and abbreviations in avionics

- Bearing (navigation)

- Breton plotter

- E6B

- Ground track

- Navigation

- Navigation room

- Rhumb line

Notes

- ^ Bartlett, Tim (February 25, 2008), Adlard Coles Book of Navigations, Adlard Coles, p. 176, ISBN 978-0713689396

- Husick, Charles B. (2009). Chapman Piloting, Seamanship and Small Boat Handling. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 927. ISBN 9781588167446.

- ^ Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) (2016-09-25). Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge: FAA-H-8083-25B. Ravenio Books.

- Michael Nolan (28 January 2010). Fundamentals of Air Traffic Control. Cengage Learning. p. 201. ISBN 1-4354-8272-7.

For example, a runway heading north would have a magnetic heading of 360°.