| Revision as of 18:17, 24 November 2006 view sourceEvice (talk | contribs)8,558 editsm →Onomatopoeic names← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:36, 26 November 2006 view source Nasz (talk | contribs)2,026 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| * In ], ''doki doki'' is used to indicate the (speeding up of the) beating of a heart (and thus excitement). | * In ], ''doki doki'' is used to indicate the (speeding up of the) beating of a heart (and thus excitement). | ||

| * Whereas in ], ''dhadak'' (''pronounced'' {{IPA|/ˈd̪əɖək/}}) is the word for a person's heartbeat, indicative of the sound of one single beat. | * Whereas in ], ''dhadak'' (''pronounced'' {{IPA|/ˈd̪əɖək/}}) is the word for a person's heartbeat, indicative of the sound of one single beat. | ||

| * in Polish ''ono ma to poeia'' mean ''it has this sound''. (ono = it, ma = has, to = this, poeia(pē'ə)~pieją, in old polish = sound. ] is abundant in onomatopoeias. Some polish onomatopoeias are hard to pronounce by not native speakers e.g. '']''. Some ] are spoken as sane phrases - ''pódźże rżnąć'' , ''kania dżży deszczu'' or full sentences - ''czjka gdzie masz jajka w perzu na talerzu'' | |||

| Sometimes onomatopoeic words can seem to have a tenuous relationship with the object they describe. Native speakers of a given language might never question the relationship; however, because words for the same basic sound can differ considerably between languages, non-native speakers might be confused by the idiomatic words of another language. For example, the sound a dog makes is ''bow-wow'' (or ''woof-woof'') in ], ''wau-wau'' in ], ''ouah-ouah'' in ], ''gaf-gaf'' in ], ''hav-hav'' in ], ''wan-wan'' in ] and ''hau-hau'' in ]. | Sometimes onomatopoeic words can seem to have a tenuous relationship with the object they describe. Native speakers of a given language might never question the relationship; however, because words for the same basic sound can differ considerably between languages, non-native speakers might be confused by the idiomatic words of another language. For example, the sound a dog makes is ''bow-wow'' (or ''woof-woof'') in ], ''wau-wau'' in ], ''ouah-ouah'' in ], ''gaf-gaf'' in ], ''hav-hav'' in ], ''wan-wan'' in ] and ''hau-hau'' in ]. | ||

Revision as of 00:36, 26 November 2006

For the supervillain, see Onomatopoeia (comics).In rhetoric, linguistics and poetry, onomatopoeia (also spelled onomatopia) is a figure of speech that employs a word, or occasionally, a grouping of words, that imitates the sound it is describing, and thus suggests its source object, such as “bang” or “click”, or animal such as “moo”, “oink”, “quack”, or “meow”.

Onomatopoeic words exist in every language, although they are different in each. For example:

- In Latin, tuxtax was the equivalent of “bam” or “whack” and was meant to imitate the sound of blows landing.

- In Ancient Greek, koax was used as the sound of a frog croaking.

- In Korean, meong meong is onomatopoeia for the sound of a dog barking.

- In Japanese, doki doki is used to indicate the (speeding up of the) beating of a heart (and thus excitement).

- Whereas in Hindi, dhadak (pronounced /ˈd̪əɖək/) is the word for a person's heartbeat, indicative of the sound of one single beat.

- in Polish ono ma to poeia mean it has this sound. (ono = it, ma = has, to = this, poeia(pē'ə)~pieją, in old polish = sound. Polish language is abundant in onomatopoeias. Some polish onomatopoeias are hard to pronounce by not native speakers e.g. chrząszcz brzmi w trzcinie. Some birds onomatopoeias are spoken as sane phrases - pódźże rżnąć , kania dżży deszczu or full sentences - czjka gdzie masz jajka w perzu na talerzu

Sometimes onomatopoeic words can seem to have a tenuous relationship with the object they describe. Native speakers of a given language might never question the relationship; however, because words for the same basic sound can differ considerably between languages, non-native speakers might be confused by the idiomatic words of another language. For example, the sound a dog makes is bow-wow (or woof-woof) in English, wau-wau in German, ouah-ouah in French, gaf-gaf in Russian, hav-hav in Hebrew, wan-wan in Japanese and hau-hau in Finnish.

Some animals are named after the sounds they make, especially birds such as the cuckoo and chickadee. In Tamil, the word for crow is Kaakaa. This practice is especially common in certain languages such as Māori and therefore in names for birds borrowed from these languages.

Uses of onomatopoeia

Some other very common English-language examples include bang, beep, splash, and ping pong. Machines and their sounds are also often usually described with onomatopoeia, as in honk or beep-beep for the horn of an automobile and vroom for the engine. For animal sounds, words like quack (duck), roar (lion), and meow (cat), are typically used in English. Some of these words are used both as nouns and as verbs.

Manner imitation

Main article: IdeophoneIn some languages, onomatopoeia-like words are used to describe phenomena apart from the purely auditive. Japanese often utilizes such words to describe feelings or figurative expressions about objects or concepts. For instance, Japanese barabara and shiiin are onomatopoeic forms reflecting a scattered state and silence, respectively. It is used in English as well with terms like "bling", which describes the shine on things like chrome, or precious stones and metals.

Onomatopoeia in advertising

Advertising uses onomatopoeia as a mnemonic so consumers will remember their products, as in Rice Krispies (US and UK) and Rice Bubbles (AU) which make a “snap, crackle, pop” when one pours on milk; or in road safety advertisements: “clunk click, every trip” (click the seatbelt on after clunking the car door closed; UK campaign) or "click, clack, front and back" (click, clack of connecting the seatbelts; AU campaign).

Onomatopoeic names

Occasionally, words for things are created from representations of the sounds these objects make. In English, for example, there is the universal fastener which is named for the onomatopoeic of the sound it makes: the zip (in the UK); less onomatopoeically zipper in the U.S.

Many birds are named from the onomatopoeic link with the calls they make, such as the Bobwhite Quail, Chickadee, the Cuckoo, the Whooping Crane, and the Whip-poor-will.

Some names for human cultures are derived from the sound of their apparently incomprehensible languages. For example, the tatars of Asia, and barbarians in Europe, named respectively by the Chinese and the Greeks.

Onomatopoeia in pop culture

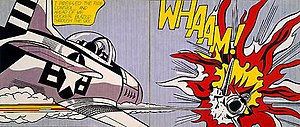

- Whaam! (1963) by Roy Lichtenstein is an early example of pop art, featuring empty fighter aircraft being struck by rockets with dazzling red and yellow explosions.

- “BAMF!”, the resulting sound Nightcrawler makes when transports himself.

- In the 1960s TV series “Batman”, comic book style onomatopoeias such as “WHAM!”, “POW!” and “CRUNCH” appear onscreen during fight scenes.

- The DC Comics superhero Green Arrow has battled a villain named Onomatopoeia.

- In the video game Final Fantasy VII, the chocobo makes the noise “Kue” (クエ) in the original Japanese versions (this has been transliterated as “Kweh” or “Wark” in the English translations).

- In an episode of Family Guy, Mike Tyson is in a spelling bee, and is given the word “onomatopoeia”. He doesn't know how to spell it, so he guesses “c”.

- In an episode of Family Guy, The Cleveland-Loretta Quagmire, Peter explains to Cleveland how Loretta was cheating on him by using "bam bam bam!" as an onomatopoeia for sexual intercourse. After Peter explains it, he tells Bamm-Bamm from The Flintstones to take it after him, going "bam bam bam!", after him, Bamm-Bamm tells cooker Emeril Lagasse to take it after him, where he finished it off by says "bam!".

See also

- Ideophone

- Japanese sound symbolism (giseigo/giongo and gitaigo)

- List of English words for sounds

- Sound symbolism

- Primal sounds

External links

- Onomatopoeia around the world

- Derek Abbott's Animal Nois

- Tutorial on Drawing Onomatopoeia (Sound Effects) in Cartoons

Notes

- Crystal pg. 176

References

Crystal, David (1997) The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language, Second Edition ISBN 0-521-55967-7

Categories: