| Revision as of 20:27, 18 June 2019 view sourceEdJohnston (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Administrators71,206 edits →Background: Nobleman -> nobleman, since it's not a title. Perhaps the second use of 'Norman' could be omitted since it's obvious?← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:36, 18 June 2019 view source Lord0fHats (talk | contribs)26 edits Just going to do them all at once instead of edit by edit. Trying to comply with a FA reviewers request and as such have introduced named figures so that they can be more readily identified by people unfamiliar with the subject of the Crusades. This includes things like identifying Augustine as a theologian, Basil II as an emperor, etc etc. I also edited tone of voice here and there to shift wording to a more encyclopedia tone. Please revert any mistakes.Next edit → | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

| The Western chronicles present the First Crusade as a surprising and unexpected event, but historical analysis has demonstrated it was foretold by a number of earlier developments in the 11th century. The city of Jerusalem had become more recognised by both laity and clerics as symbolic of penitential devotion. There is evidence that segments of the western noble class were willing to accept a doctrine of papal governance in military matters. The ] hold on the holy city was weak and the Byzantines were open to the opportunity presented by western military aid for specific campaigns against the Seljuqs. This presented the papacy with a chance to reinforce the principle of papal sovereignty with a display of military power such as that proposed by ] in 1074 but not followed through.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=46}}</ref> Warfare was endemic in Western Europe in this period with violence often a part of political discourse. Contemporaries recognised the moral danger which the papacy attempted to deal with by permitting or even encouraging certain types of warfare. However, the Christian population had a desire for a more effective church which evidenced itself in rioting in Italy and a greater general level of piety. This prompted investment and growth in monasteries across England, France and Germany. Pilgrimage to the Holy Land began in the fourth century but expanded after safer routes through Hungary developed from 1000. It was an increasingly articulate piety within the knighthood and the normative devotional and penitential practises of the aristocracy that created a fertile ground for crusading appeals.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=35–38}}</ref> | The Western chronicles present the First Crusade as a surprising and unexpected event, but historical analysis has demonstrated it was foretold by a number of earlier developments in the 11th century. The city of Jerusalem had become more recognised by both laity and clerics as symbolic of penitential devotion. There is evidence that segments of the western noble class were willing to accept a doctrine of papal governance in military matters. The ] hold on the holy city was weak and the Byzantines were open to the opportunity presented by western military aid for specific campaigns against the Seljuqs. This presented the papacy with a chance to reinforce the principle of papal sovereignty with a display of military power such as that proposed by ] in 1074 but not followed through.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=46}}</ref> Warfare was endemic in Western Europe in this period with violence often a part of political discourse. Contemporaries recognised the moral danger which the papacy attempted to deal with by permitting or even encouraging certain types of warfare. However, the Christian population had a desire for a more effective church which evidenced itself in rioting in Italy and a greater general level of piety. This prompted investment and growth in monasteries across England, France and Germany. Pilgrimage to the Holy Land began in the fourth century but expanded after safer routes through Hungary developed from 1000. It was an increasingly articulate piety within the knighthood and the normative devotional and penitential practises of the aristocracy that created a fertile ground for crusading appeals.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=35–38}}</ref> | ||

| Prior to the mid 11th century ] rival Roman noble families and the Holy Roman Emperor competed to control a Papacy that amounted to little more than a localised bishopric. The Roman families appointed relatives and protégés as popes, <ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=24}}</ref> while ] invaded Rome and replaced two rival candidates with his own nominee. The reforming movement coalesced around ], intent on the abolition of ] and ] along with the implementation of a ] responsible for the election of future popes.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=25}}</ref> This movement established an assertive, reformist papacy eager to increase its power and influence over secular Europe. A power struggle between ] began around 1075 and continued through the period of the First Crusade over whether the Catholic Church or the ] held the right to appoint church officials and other clerics that is now known as the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Rubenstein|2011|p=18}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Cantor|1958|pp=8–9}}</ref> In order to gather military resources for his conflict with the Emperor, ] developed a system of recruitment via oaths that ] extended into a network across Europe. This also supported the development of a doctrine of holy war developed from the thinking of ] on the treatment of heresy. Death in a just war became to be seen as martyrdom and warfare itself as a penitential activity.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=26–27}}</ref> Gregory’s doctrine of papal primacy led to conflict with eastern Christians where the traditional view was that the Pope was only one, amongst the five, patriarchs of the church alongside the ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=27–30}}</ref> Ultimately this led to ], the name now given to the split in the Christian church between the Latin West and the Orthodox East in 1054.<ref>{{Harvnb|Mayer |1988|pp=2–3}}</ref> | Prior to the mid 11th century ] rival Roman noble families and the Holy Roman Emperor competed to control a Papacy that amounted to little more than a localised bishopric. The Roman families appointed relatives and protégés as popes, <ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=24}}</ref> while ] invaded Rome and replaced two rival candidates with his own nominee. The reforming movement coalesced around ], intent on the abolition of ] and ] along with the implementation of a ] responsible for the election of future popes.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=25}}</ref> This movement established an assertive, reformist papacy eager to increase its power and influence over secular Europe. A power struggle between ] began around 1075 and continued through the period of the First Crusade over whether the Catholic Church or the ] held the right to appoint church officials and other clerics that is now known as the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Rubenstein|2011|p=18}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Cantor|1958|pp=8–9}}</ref> In order to gather military resources for his conflict with the Emperor, ] developed a system of recruitment via oaths that ] extended into a network across Europe. This also supported the development of a doctrine of holy war developed from the thinking of 3rd and 4th Century Theologian ] on the treatment of heresy. Death in a just war became to be seen as martyrdom and warfare itself as a penitential activity.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=26–27}}</ref> Gregory’s doctrine of papal primacy led to conflict with eastern Christians where the traditional view was that the Pope was only one, amongst the five, patriarchs of the church alongside the ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=27–30}}</ref> Ultimately this led to ], the name now given to the split in the Christian church between the Latin West and the Orthodox East in 1054.<ref>{{Harvnb|Mayer |1988|pp=2–3}}</ref> | ||

| In the Eastern Mediterranean the arrival of the Seljuqs disrupted the status quo between the 1040s and 1060s. They were a Turkish tribe recently converted to Islam. The Seljuqs followed the Sunni tradition which quickly brought them into conflict with the ] ] who had ruled Egypt since 969, independent from the ] ] rulers in Baghdad and with a rival Shi'ite caliph{{snd}}considered the successor to the Muslim prophet Mohammad. However, the conquered indigenous Arabs lived under the Seljuqs in relative peace and prosperity. In 1092 the relative stability began to disintegrate following the death of the vizier, ], who had been the effective ruler closely followed by the death of the Sultan. One result of this confrontation within Islam was that the Islamic world disregarded the world beyond and this made the Muslim vulnerable to the surprise present by the First Crusade. <ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=39–41}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=41}}</ref> | In the Eastern Mediterranean the arrival of the Seljuqs disrupted the status quo between the 1040s and 1060s. They were a Turkish tribe recently converted to Islam. The Seljuqs followed the Sunni tradition which quickly brought them into conflict with the ] ] who had ruled Egypt since 969, independent from the ] ] rulers in Baghdad and with a rival Shi'ite caliph{{snd}}considered the successor to the Muslim prophet Mohammad. However, the conquered indigenous Arabs lived under the Seljuqs in relative peace and prosperity. In 1092 the relative stability began to disintegrate following the death of the vizier, ], who had been the effective ruler closely followed by the death of the Sultan. One result of this confrontation within Islam was that the Islamic world disregarded the world beyond and this made the Muslim vulnerable to the surprise present by the First Crusade. <ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=39–41}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=41}}</ref> | ||

| Through military successes under ] the Byzantine Empire had reached a zenith in 1025. Its frontiers stretched as far East as Iran, it controlled Bulgaria as well as much of southern Italy and piracy had been suppressed in the Mediterranean Sea. However from this point the arrival of new enemies on all frontiers placed intolerable strains on the resources of the state. In Italy they were confronted by the ], to the north the ], ], the ] as well as the Seljuqs. ] attempted to confront the Seljuqs to suppress sporadic raiding leading to the 1071 defeat of the Byzantine army at the ]. This was once considered a pivotal event by historians but is now regarded as only one further step in the expansion of the ] into ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=27}}</ref> This situation was probably the cause of instability in the Byzantine hierarchy rather than the result. In order to maintain order the Emperors were forced to recruit mercenary armies, sometimes from the very forces that provided the threat. Despite all this recent scholarship has identified encouraging positive signs in the health of the Empire.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=42–46}}</ref> | Through military successes under Emperor ] the Byzantine Empire had reached a zenith in 1025. Its frontiers stretched as far East as Iran, it controlled Bulgaria as well as much of southern Italy and piracy had been suppressed in the Mediterranean Sea. However from this point the arrival of new enemies on all frontiers placed intolerable strains on the resources of the state. In Italy they were confronted by the ], to the north the ], ], the ] as well as the Seljuqs. ] attempted to confront the Seljuqs to suppress sporadic raiding leading to the 1071 defeat of the Byzantine army at the ]. This was once considered a pivotal event by historians but is now regarded as only one further step in the expansion of the ] into ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=27}}</ref> This situation was probably the cause of instability in the Byzantine hierarchy rather than the result. In order to maintain order the Emperors were forced to recruit mercenary armies, sometimes from the very forces that provided the threat. Despite all this recent scholarship has identified encouraging positive signs in the health of the Empire.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=42–46}}</ref> | ||

| ==In the Eastern Mediterranean== | ==In the Eastern Mediterranean== | ||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

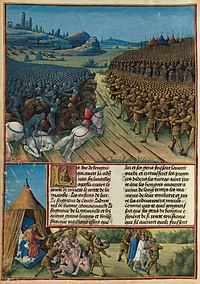

| ] leading the People's Crusade (] 1500, Avignon, 14th century)|alt=14th century miniature of Peter the Hermit leading the People's Crusade]] | ] leading the People's Crusade (] 1500, Avignon, 14th century)|alt=14th century miniature of Peter the Hermit leading the People's Crusade]] | ||

| Almost immediately ] led thousands of mostly poor Christians out of Europe in what became known as the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=20–21}}</ref> He claimed he had a letter from heaven instructing Christians to prepare for the imminent ] by seizing Jerusalem.<ref>{{Harvnb|Slack|2013|pp=228–30}}</ref> The motivations of this Crusade included a "] of the poor" inspired by an expected mass ascension into heaven at Jerusalem.<ref name="Cohn 1970 61, 64">{{Harvnb|Cohn|1970|pp=61, 64}}</ref> Germany witnessed the first incidents of major violent European ] when these Crusaders massacred Jewish communities in what became known as the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Slack|2013|pp=108–09}}</ref> In Speyer, Worms, Mainz, and Cologne the range of anti-Jewish activity was broad, extending from limited, spontaneous violence to full-scale military attacks.<ref>{{Harvnb|Chazan|1996|p=60}}</ref> In parts of ] and Germany, Jews were perceived as just as much an enemy as Muslims: they were held responsible for the ], and they were more immediately visible than the distant Muslims. Many people wondered why they should travel thousands of miles to fight non-believers when there were already non-believers closer to home.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tyerman|2007|pp=99-100}}</ref> The Crusaders journeyed, despite advice from Alexios' to wait for the nobles, to ]. Only 3000 survived an ambush by the Turks at the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|p=23}}</ref> | Almost immediately, the French priest ] led thousands of mostly poor Christians out of Europe in what became known as the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=20–21}}</ref> He claimed he had a letter from heaven instructing Christians to prepare for the imminent ] by seizing Jerusalem.<ref>{{Harvnb|Slack|2013|pp=228–30}}</ref> The motivations of this Crusade included a "] of the poor" inspired by an expected mass ascension into heaven at Jerusalem.<ref name="Cohn 1970 61, 64">{{Harvnb|Cohn|1970|pp=61, 64}}</ref> Germany witnessed the first incidents of major violent European ] when these Crusaders massacred Jewish communities in what became known as the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Slack|2013|pp=108–09}}</ref> In Speyer, Worms, Mainz, and Cologne the range of anti-Jewish activity was broad, extending from limited, spontaneous violence to full-scale military attacks.<ref>{{Harvnb|Chazan|1996|p=60}}</ref> In parts of ] and Germany, Jews were perceived as just as much an enemy as Muslims: they were held responsible for the ], and they were more immediately visible than the distant Muslims. Many people wondered why they should travel thousands of miles to fight non-believers when there were already non-believers closer to home.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tyerman|2007|pp=99-100}}</ref> The Crusaders journeyed, despite advice from Alexios' to wait for the nobles, to ]. Only 3000 survived an ambush by the Turks at the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|p=23}}</ref> | ||

| Both ] and ] were in conflict with Urban and declined to participate in the official crusade. However, members of the high aristocracy from France, western Germany, the Low countries, and Italy were drawn to the venture, commanding their own military contingents in loose, fluid arrangements based on bonds of lordship, family, ethnicity, and language. Foremost amongst these was the elder statesman, ]. He was rivalled by the relatively poor but martial ] and his nephew ] from the Norman community of southern Italy. They were joined by ] and his brother ] in leading a loose conglomerate from ], ], and ]. These five princes were pivotal to the campaign that was also joined by a Northern French army led by ], ], and ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=43–47}}</ref> The armies, which may have contained as many as 100,000 people, including non-combatants, travelled eastward by land to Byzantium where they were cautiously welcomed by the Emperor.<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=30–31}}</ref> Alexios persuaded many of the princes to pledge allegiance to him and that their first objective should be Nicaea, |

Both King ] and ] were in conflict with Urban and declined to participate in the official crusade. However, members of the high aristocracy from France, western Germany, the Low countries, and Italy were drawn to the venture, commanding their own military contingents in loose, fluid arrangements based on bonds of lordship, family, ethnicity, and language. Foremost amongst these was the elder statesman, ]. He was rivalled by the relatively poor but martial ] and his nephew ] from the Norman community of southern Italy. They were joined by ] and his brother ] in leading a loose conglomerate from ], ], and ]. These five princes were pivotal to the campaign that was also joined by a Northern French army led by ], ], and ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=43–47}}</ref> The armies, which may have contained as many as 100,000 people, including non-combatants, travelled eastward by land to Byzantium where they were cautiously welcomed by the Emperor.<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=30–31}}</ref> Alexios persuaded many of the princes to pledge allegiance to him and that their first objective should be Nicaea, where Sultan ] established the capital of the ]. Having already destroyed the earlier People's Crusade, the over-confident Sultan left the city to resolve a territorial dispute, enabling its ] in 1097 after a Crusader siege and a Byzantine naval assault. This marked a high point in Latin and Greek co-operation and also the start of Crusader attempts to take advantage of political and religious disunity in the Muslim world: Crusader envoys were sent to Egypt seeking an alliance.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=52–56}}</ref> | ||

| The Crusades' first experience with the Turkish tactic of lightly armoured mounted archers occurred when an advanced party led by Bohemond and Duke Robert was ambushed at ]. The Normans resisted for hours before the arrival of the main army caused a Turkish withdrawal. After this, the nomadic Seljuks avoided the Crusade.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=57–59}}</ref> The factionalism amongst the Turks that followed the death of ] meant they did not present a united opposition. Instead, ] and ] had competing rulers.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=21–22}}</ref> The three-month march to ] was arduous, with numbers reduced by starvation, thirst, and disease, combined with the decision of Baldwin to leave with 100 knights in order to carve out his own territory in Edessa.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=59–61}}</ref> The Crusaders embarked on an eight-month ] but lacked the resources to fully invest the city; similarly, the residents lacked the resources to repel the invaders. Eventually, Bohemond persuaded a tower guard in the city to open a gate and the Crusaders entered, massacring the Muslim and many Christian Greeks, Syrian and Armenian inhabitants.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=72–73}}</ref> | The Crusades' first experience with the Turkish tactic of lightly armoured mounted archers occurred when an advanced party led by Bohemond and Duke Robert was ambushed at ]. The Normans resisted for hours before the arrival of the main army caused a Turkish withdrawal. After this, the nomadic Seljuks avoided the Crusade.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=57–59}}</ref> The factionalism amongst the Turks that followed the death of ], the Sultan of the Seljuq Empire, meant they did not present a united opposition. Instead, ] and ] had competing rulers.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=21–22}}</ref> The three-month march to ] was arduous, with numbers reduced by starvation, thirst, and disease, combined with the decision of Baldwin to leave with 100 knights in order to carve out his own territory in Edessa.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=59–61}}</ref> The Crusaders embarked on an eight-month ] but lacked the resources to fully invest the city; similarly, the residents lacked the resources to repel the invaders. Eventually, Bohemond persuaded a tower guard in the city to open a gate and the Crusaders entered, massacring the Muslim and many Christian Greeks, Syrian and Armenian inhabitants.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=72–73}}</ref> | ||

| Sunni Islam |

The Sunni Islam world recognized the threat posed by the crusades following Antioch's fall. The sultan of Baghdad raised a force to recapture the city led by the Iraqi general ]. The Byzantines provided no assistance to the Crusaders' defence of the city because the deserting Stephen of Blois told them the cause was lost. Losing numbers through desertion and starvation in the besieged city, the Crusaders attempted to negotiate surrender, but were rejected by Kerbogha, who wanted to destroy them permanently. Morale within the city rose when ] claimed to have discovered the ]. Bohemond recognised that the only option now was for open combat, and he launched a counterattack against the besiegers. Despite superior numbers, Kerbogha's army, which was divided into factions and surprised by the commitment and dedication of the Franks, retreated and abandoned the siege.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge |2012|pp=72–82}}</ref> The Crusaders then delayed for months while they argued over who would have the captured territory. Debate ended only when news arrived that the Fatimid Egyptians had taken Jerusalem from the Turks, and it became imperative to attack before the Egyptians could consolidate their position. Bohemond remained in Antioch, retaining the city despite his pledge that to return it to Byzantine control, while Raymond led the remaining Crusader army ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=146–53}}</ref> | ||

| An initial attack on the city failed and, due to the Crusaders' lack of resources, the ] became a stalemate. However, the arrival of craftsman and supplies transported by the Genoese to ] tilted the balance in their favour. Crusaders constructed two large siege engines; the one commanded by Godfrey breached the walls on 15{{nbsp}}July 1099. For two days the Crusaders massacred the inhabitants and pillaged the city. Historians now believe the accounts of the numbers killed have been exaggerated, but this narrative of massacre did much to cement the Crusaders' reputation for barbarism.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=96–103}}</ref> Godfrey further secured the Frankish position by surprising the Egyptian relief force commanded by the vizier of the Fatimid Caliph, ], at ]. This relief force retreated to Egypt, with the vizier fleeing by ship.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=104–06}}</ref> At this point most of the Crusaders considered their pilgrimage complete and returned to Europe, leaving behind Godfrey with a mere 300 knights and 2,000 infantry to defend Palestine. Of the other princes, only Tancred remained with the ambition to gain his own princedom.<ref name="Asbridge 2012 106">{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=106}}</ref> | An initial attack on the city failed and, due to the Crusaders' lack of resources, the ] became a stalemate. However, the arrival of craftsman and supplies transported by the Genoese to ] tilted the balance in their favour. Crusaders constructed two large siege engines; the one commanded by Godfrey breached the walls on 15{{nbsp}}July 1099. For two days the Crusaders massacred the inhabitants and pillaged the city. Historians now believe the accounts of the numbers killed have been exaggerated, but this narrative of massacre did much to cement the Crusaders' reputation for barbarism.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=96–103}}</ref> Godfrey further secured the Frankish position by surprising the Egyptian relief force commanded by the vizier of the Fatimid Caliph, ], at ]. This relief force retreated to Egypt, with the vizier fleeing by ship.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=104–06}}</ref> At this point most of the Crusaders considered their pilgrimage complete and returned to Europe, leaving behind Godfrey with a mere 300 knights and 2,000 infantry to defend Palestine. Of the other princes, only Tancred remained with the ambition to gain his own princedom.<ref name="Asbridge 2012 106">{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=106}}</ref> | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

| {{Main|Second Crusade| Third Crusade | German Crusade}} | {{Main|Second Crusade| Third Crusade | German Crusade}} | ||

| ] (illustration of ]'s ''Histoire d'Outremer'', 1337) |alt= Medieval illustration of a battle during the Second Crusade]] | ] (illustration of ]'s ''Histoire d'Outremer'', 1337) |alt= Medieval illustration of a battle during the Second Crusade]] | ||

| Under the papacies of successive Popes smaller groups of Crusaders continued to travel to the Eastern Mediterranean to fight the Muslims and aid the Crusader States in the early 12th{{nbsp}}century. The third decade saw campaigns by ], the ], and ] and the foundation of the ]{{mdash}}a foundation of warrior monks which became international, widely influential and provided the Crusader States with a standing army that is estimated to have formed half of the states military forces.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=144–45}}</ref> The period also saw the innovation of granting ]s to those who opposed papal enemies, and this marked the beginning of politically motivated Crusades.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=146–47}}</ref> The loss of Aleppo in 1128 and ] (]) in 1144 to ], governor of ], led to preaching for what subsequently became known as the Second Crusade.<ref>{{Harvnb|Riley-Smith|2005|pp=104–05}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=144}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=71–74}}</ref> ] and Conrad{{nbsp}}III led armies from France and Germany to Jerusalem and Damascus without winning any major victories.<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=77–85}}</ref> As in the First Crusade, the preaching led to attacks on ] including massacres in the ], ], ], ] and ] amid claims that the Jews were not contributing financially to the rescue of the Holy Land. ], who had encouraged the Second Crusade in his preaching, was so perturbed by the violence that he journeyed from Flanders to Germany to deal with the problem.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tyerman|2006|pp=281–88}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|p=77}}</ref> | Under the papacies of successive Popes, smaller groups of Crusaders continued to travel to the Eastern Mediterranean to fight the Muslims and aid the Crusader States in the early 12th{{nbsp}}century. The third decade saw campaigns by French noblemen ], the ], and King ] and the foundation of the ]{{mdash}}a foundation of warrior monks which became international, widely influential and provided the Crusader States with a standing army that is estimated to have formed half of the states military forces.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=144–45}}</ref> The period also saw the innovation of granting ]s to those who opposed papal enemies, and this marked the beginning of politically motivated Crusades.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=146–47}}</ref> The loss of Aleppo in 1128 and ] (]) in 1144 to ], governor of ], led to preaching for what subsequently became known as the Second Crusade.<ref>{{Harvnb|Riley-Smith|2005|pp=104–05}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=144}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=71–74}}</ref> ] and Conrad{{nbsp}}III led armies from France and Germany to Jerusalem and Damascus without winning any major victories.<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=77–85}}</ref> As in the First Crusade, the preaching led to attacks on ] including massacres in the ], ], ], ] and ] amid claims that the Jews were not contributing financially to the rescue of the Holy Land. French abbot ], who had encouraged the Second Crusade in his preaching, was so perturbed by the violence that he journeyed from Flanders to Germany to deal with the problem.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tyerman|2006|pp=281–88}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|p=77}}</ref> | ||

| The rise of systemic and murderous political intrigue in Egypt led to the deposition of the vizier, ], and encouraged ] to plan an invasion. The invasion was only halted |

The rise of systemic and murderous political intrigue in Egypt led to the deposition of the vizier, ], and encouraged King ] to plan an invasion. The invasion was only halted by Egypt's tribute of 160,000 gold ]s. In 1163 Shawar visited ], Zengi's son and successor, in Damascus seeking political and military support. Some historians have considered Nur ad-Din's support as a visionary attempt to surround the Crusaders, but in practice he prevaricated before responding only when it became clear that the Crusaders might gain an unassailable foothold on the Nile. Nur ad-Din sent his Kurdish general, ], who stormed Egypt and restored Shawar. However, Shawar asserted his independence and allied with Baldwin's brother and successor King ]. When Amalric broke the alliance in a ferocious attack, Shawar again requested military support from Syria, and Shirkuh was sent by Nur ad-Din for a second time. Amalric retreated, but the victorious Shirkuh had Shawar executed and was appointed vizier. Barely two months later he died, to be succeeded by his nephew, Yusuf ibn Ayyub, who has become known by his honorific 'Salah al-Din', 'the goodness of faith', which in turn has become westernised as ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=272–75}}</ref> Nur ad-Din died in 1174. He was the first Muslim to unite Aleppo and Damascus in the Crusade era. Some Islamic contemporaries promoted the idea that there was a natural Islamic resurgence under Zengi, through Nur al-Din to Saladin although this was not as straightforward and simple as it appears. Saladin imprisoned all the caliph's heirs, preventing them from having children, as opposed to having them all killed, which would have been normal practice, to extinguish the bloodline. Assuming control after the death of his overlord, Nur al-Din, Saladin had the strategic choice of establishing Egypt as an autonomous power or attempting to become the pre-eminent Muslim in the Eastern Mediterranean{{snd}}he chose the latter.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=282–86}}</ref> | ||

| ] arriving in the Eastern Mediterranean (] 16 G VI, mid-14th{{nbsp}}century) |alt=Miniature of Phillip of France arriving in the Eastern Mediterranean]] | ] arriving in the Eastern Mediterranean (] 16 G VI, mid-14th{{nbsp}}century) |alt=Miniature of Phillip of France arriving in the Eastern Mediterranean]] | ||

| As Nur al-Din's territories became fragmented after his death, ] legitimised his ascent by positioning himself as a defender of Sunni Islam subservient to both the Caliph of Baghdad and Nur al-Din's son and successor, ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=287–88}}</ref> In the early years of his ascendency, he seized Damascus and much of Syria, but not Aleppo.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=292}}</ref> After building a defensive force to resist a planned attack by the Kingdom of Jerusalem that never materialised, his first contest with the Latin Christians was not a success. His overconfidence and tactical errors led to defeat at the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=307–08}}</ref> Despite this setback, Saladin established a domain stretching from the Nile to the Euphrates through a decade of politics, coercion, and low-level military action.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=322}}</ref> After a life-threatening illness early in 1186, he determined to make good on his propaganda as the champion of Islam, embarking on heightened campaigning against the Latin Christians.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=333–36}}</ref> ] responded by raising the largest army that Jerusalem had ever put in the field. However, Saladin lured the force into inhospitable terrain without water supplies, surrounded the Latins with a superior force, and routed them at the ]. Saladin offered the Christians the option of remaining in peace under Islamic rule or taking advantage of 40 days' grace to leave. As a result, much of Palestine quickly fell to Saladin including, after a short five-day ], Jerusalem.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=343–57}}</ref> According to ], ] died of deep sadness on 19{{nbsp}}October 1187 on hearing of the defeat.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=367}}</ref> His successor as Pope, ] issued a ] titled '']'' that proposed a further Crusade later named the ] to recapture Jerusalem. On 28{{nbsp}}August 1189 ] ] the strategic city of Acre, only to be in turn besieged by Saladin.<ref name="Asbridge 2012 686">{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=686}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=398–405}}</ref> Both armies could be supplied by sea so a long stalemate commenced. |

As Nur al-Din's territories became fragmented after his death, ] legitimised his ascent by positioning himself as a defender of Sunni Islam subservient to both the Caliph of Baghdad and Nur al-Din's son and successor, ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=287–88}}</ref> In the early years of his ascendency, he seized Damascus and much of Syria, but not Aleppo.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=292}}</ref> After building a defensive force to resist a planned attack by the Kingdom of Jerusalem that never materialised, his first contest with the Latin Christians was not a success. His overconfidence and tactical errors led to defeat at the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=307–08}}</ref> Despite this setback, Saladin established a domain stretching from the Nile to the Euphrates through a decade of politics, coercion, and low-level military action.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=322}}</ref> After a life-threatening illness early in 1186, he determined to make good on his propaganda as the champion of Islam, embarking on heightened campaigning against the Latin Christians.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=333–36}}</ref> ] responded by raising the largest army that Jerusalem had ever put in the field. However, Saladin lured the force into inhospitable terrain without water supplies, surrounded the Latins with a superior force, and routed them at the ]. Saladin offered the Christians the option of remaining in peace under Islamic rule or taking advantage of 40 days' grace to leave. As a result, much of Palestine quickly fell to Saladin including, after a short five-day ], Jerusalem.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=343–57}}</ref> According to ], ] died of deep sadness on 19{{nbsp}}October 1187 on hearing of the defeat.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=367}}</ref> His successor as Pope, ] issued a ] titled '']'' that proposed a further Crusade later named the ] to recapture Jerusalem. On 28{{nbsp}}August 1189 ] ] the strategic city of Acre, only to be in turn besieged by Saladin.<ref name="Asbridge 2012 686">{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=686}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=398–405}}</ref> Both armies could be supplied by sea so a long stalemate commenced. However, the Crusaders became so deprived at times they are thought to have resorted to cannibalism.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=424}}</ref> | ||

| The journey to the Eastern Mediterranean was inevitably long and eventful. Travelling overland, ], drowned in the ], and few of his men reached the Eastern Mediterranean.<ref>{{harvnb|Tyerman|2007|pp=35–36}}</ref> Travelling by sea, ] conquered Cyprus in 1191 in response to his sister and fiancée, who were travelling separately, being taken captive by the island's ruler, ].<ref>{{harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=429–30}}</ref> ] was the first king to arrive at the siege of Acre; Richard arrived on 8{{nbsp}}June 1191.<ref name="Asbridge 2012 686"/> The arrival of the French and Angevin forces turned the tide in the conflict, and the Muslim garrison of Acre finally surrendered on 12{{nbsp}}July. Philip considered his vow fulfilled and returned to France to deal with domestic matters, leaving most of his forces behind. But Richard travelled south along the Mediterranean coast, defeated the Muslims near ], and recaptured the port city of ]. He twice advanced to within a day's march of Jerusalem before judging that he lacked the resources to successfully capture the city, or defend it in the unlikely event of a successful assault, while Saladin had a mustered army. This marked the end of Richard's crusading career and was a calamitous blow to Frankish morale.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=509}}</ref> A three-year truce was negotiated that allowed Catholics unfettered access to Jerusalem.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=512–13}}</ref> Politics in England and illness forced Richard's departure, never to return, and Saladin died in March 1193.<ref name="Asbridge 2012 686"/> ] initiated the ] to fulfil the promises made by his father, Frederick, to undertake a Crusade to the Holy Land. Led by ], ], the army captured the cities of ] and ]. However, in 1197 Henry died and most of the Crusaders returned to Germany to protect their holdings and take part in the election of his successor as Emperor.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=155}}</ref> | The journey to the Eastern Mediterranean was inevitably long and eventful. Travelling overland, ], drowned in the ], and few of his men reached the Eastern Mediterranean.<ref>{{harvnb|Tyerman|2007|pp=35–36}}</ref> Travelling by sea, ] conquered Cyprus in 1191 in response to his sister and fiancée, who were travelling separately, being taken captive by the island's ruler, ].<ref>{{harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=429–30}}</ref> ] was the first king to arrive at the siege of Acre; Richard arrived on 8{{nbsp}}June 1191.<ref name="Asbridge 2012 686"/> The arrival of the French and Angevin forces turned the tide in the conflict, and the Muslim garrison of Acre finally surrendered on 12{{nbsp}}July. Philip considered his vow fulfilled and returned to France to deal with domestic matters, leaving most of his forces behind. But Richard travelled south along the Mediterranean coast, defeated the Muslims near ], and recaptured the port city of ]. He twice advanced to within a day's march of Jerusalem before judging that he lacked the resources to successfully capture the city, or defend it in the unlikely event of a successful assault, while Saladin had a mustered army. This marked the end of Richard's crusading career and was a calamitous blow to Frankish morale.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=509}}</ref> A three-year truce was negotiated that allowed Catholics unfettered access to Jerusalem.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=512–13}}</ref> Politics in England and illness forced Richard's departure, never to return, and Saladin died in March 1193.<ref name="Asbridge 2012 686"/> ] initiated the ] to fulfil the promises made by his father, Frederick, to undertake a Crusade to the Holy Land. Led by ], ], the army captured the cities of ] and ]. However, in 1197 Henry died and most of the Crusaders returned to Germany to protect their holdings and take part in the election of his successor as Emperor.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=155}}</ref> | ||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

| {{Main|Fourth Crusade| Latin Empire|Frankokratia|Siege of Constantinople (1203)|Sack of Constantinople (1204)| Battle of Adrianople (1205)|Siege of Zara|Fifth Crusade| Sixth Crusade| Barons' Crusade|Siege of Jerusalem (1244)| Seventh Crusade|War of Saint Sabas| Eighth Crusade|Ninth Crusade| Sicilian Vespers|Fall of Tripoli (1289)|Siege of Acre (1291)}} | {{Main|Fourth Crusade| Latin Empire|Frankokratia|Siege of Constantinople (1203)|Sack of Constantinople (1204)| Battle of Adrianople (1205)|Siege of Zara|Fifth Crusade| Sixth Crusade| Barons' Crusade|Siege of Jerusalem (1244)| Seventh Crusade|War of Saint Sabas| Eighth Crusade|Ninth Crusade| Sicilian Vespers|Fall of Tripoli (1289)|Siege of Acre (1291)}} | ||

| ] of the ] city of ] by the Crusaders in 1204 (BNF ] 5090, 15th century)|alt=Image of siege of Constantinople]] | ] of the ] city of ] by the Crusaders in 1204 (BNF ] 5090, 15th century)|alt=Image of siege of Constantinople]] | ||

| ] |

] began preaching what became the Fourth Crusade in 1200, primarily in France but also in England and Germany.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tyerman |2006|pp=502–08}}</ref> This Crusade was diverted by the ], the ruler of Venice elected by members of the ], ] and King ] to further their aggressive territorial objectives. Dandolo aimed to expand Venice's power in the Eastern Mediterranean, and Philip intended to restore his exiled nephew, ], along with Angelos's father, ], to the throne of Byzantium. This would require overthrowing the present ruler, ], the uncle of Alexios IV.<ref name="Davies 1997 359–360">{{Harvnb|Davies|1997|pp=359–60}}</ref> The Crusaders were unable to pay the Venetians for a fleet due to insufficiency of numbers, so they agreed to divert the Crusade to attack Constantinople and share what could be looted as payment. The Crusaders seized the Christian city of ] as collateral; Innocent was appalled, and promptly excommunicated them.<ref name="Lock 2006 158–159">{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=158–59}}</ref> After the Crusades took Constantinople for a first time, the original purpose of the campaign was defeated by the assassination of Alexios{{nbsp}}IV Angelos. As a result, the Crusaders attacked the city for a second time and this time ] it which involved the pillaging of churches and the killing many of the citizens. The result was that the Fourth Crusade never came within 1,000 miles of its objective of Jerusalem.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge |2012|p=530}}</ref> | ||

| The 13th century a new military threat to the civilised world as the ] swept East from ] through southern Russia, Poland and Hungary while also defeating the Seljuks and threatening the Crusader states.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=237-38}}</ref> Separately, Europe saw popular outbursts of ecstatic piety in support of the Crusades such as that resulting in the ] in 1212. Large groups of young adults and children spontaneously gathered, believing their innocence would enable success where their elders had failed. Few, if any at all, journeyed to the Eastern Mediterranean. Although little reliable evidence survives for these events, they provide an indication of how hearts and minds could be engaged for the cause.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=533–35}}</ref> | The 13th century saw a new military threat to the civilised world as the ] swept East from ] through southern Russia, Poland and Hungary while also defeating the Seljuks and threatening the Crusader states.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=237-38}}</ref> Separately, Europe saw popular outbursts of ecstatic piety in support of the Crusades, such as that resulting in the ] in 1212. Large groups of young adults and children spontaneously gathered, believing their innocence would enable success where their elders had failed. Few, if any at all, journeyed to the Eastern Mediterranean. Although little reliable evidence survives for these events, they provide an indication of how hearts and minds could be engaged for the cause.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=533–35}}</ref> | ||

| ]'s '']''(] ms. Chigiano L VIII 296, 14th century).]] | ]'s '']''(] ms. Chigiano L VIII 296, 14th century).]] | ||

| Following Innocent III's ], crusading resumed in 1217 against Saladin's ] successors in Egypt and Syria for what is classified as the ]. Led by ] and ], forces drawn mainly from Hungary, Germany, Flanders, and ] achieved little. Leopold and ] besieged and captured ] but an army advancing into Egypt was compelled to surrender.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=168–69}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Riley-Smith|2005|pp=179–80}}</ref> Damietta was returned and an eight-year truce agreed.<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=561–62}}</ref> ], was excommunicated for breaking a treaty obligation with the Pope that required him to lead a crusade. However, since his marriage |

Following Innocent III's ], crusading resumed in 1217 against Saladin's ] successors in Egypt and Syria for what is classified as the ]. Led by King ] and ], forces drawn mainly from Hungary, Germany, Flanders, and ] achieved little. Leopold and ], the King of Jerusalem and later Latin Emperor of Constantinople, besieged and captured ] but an army advancing into Egypt was compelled to surrender.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=168–69}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Riley-Smith|2005|pp=179–80}}</ref> Damietta was returned and an eight-year truce agreed.<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=561–62}}</ref> ], was excommunicated for breaking a treaty obligation with the Pope that required him to lead a crusade. However, since his marriage ], John of Brienne's daughter and heir, gave him a claim to the kingdom of Jerusalem, he finally arrived at Acre in 1228. Frederick was culturally the Christian monarch most empathetic to the Muslim world, having grown up in Sicily, with a Muslim bodyguard and even a harem. His great diplomatic skills meant that the ] was largely negotiation supported by force.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=566–71}}</ref> A peace treaty was agreed upon, giving Latin Christians most of Jerusalem and a strip of territory that linked the city to Acre, while the Muslims controlled their sacred areas. In return, an alliance was made with ], ], against all of his enemies of whatever religion. The treaty and suspicions about Frederick's ambitions in the region made him unpopular, and he was forced to return to his domains when they were attacked by ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=569}}</ref> While the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy were in conflict, it often fell to secular leaders to campaign. What is sometimes known as the ] was led by Count ] and Earl ]; it combined forceful diplomacy and the playing of rival Ayyubid factions off against each other.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=573}}</ref> This brief renaissance for Frankish Jerusalem was illusory, being dependent on Ayyubid weakness and division following the death of Al-Kamil.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=574}}</ref> | ||

| In 1244 a band of ] mercenaries travelling to Egypt to serve ], seemingly of their own volition, ] en route and defeated a combined Christian and Syrian army at the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=574–76}}</ref> In response, Louis{{nbsp}}IX, king of France, organised a Crusade, called the ], to attack Egypt, arriving in 1249.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tyerman |2006|pp=770–75}}</ref> It was not a success. Louis was defeated at ] and captured as he retreated to Damietta.<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=194–95}}</ref> Another truce was agreed upon for a ten-year period, and Louis was ransomed. Louis remained in Syria until 1254 to consolidate the Crusader states.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=178}}</ref> From 1265 to 1271, the Mamluk sultan ] drove the Franks to a few small coastal outposts.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tyerman|2006|pp=816–17}}</ref> | In 1244 a band of ] mercenaries travelling to Egypt to serve ], seemingly of their own volition, ] en route and defeated a combined Christian and Syrian army at the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=574–76}}</ref> In response, Louis{{nbsp}}IX, king of France, organised a Crusade, called the ], to attack Egypt, arriving in 1249.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tyerman |2006|pp=770–75}}</ref> It was not a success. Louis was defeated at ] and captured as he retreated to Damietta.<ref>{{Harvnb|Hindley|2004|pp=194–95}}</ref> Another truce was agreed upon for a ten-year period, and Louis was ransomed. Louis remained in Syria until 1254 to consolidate the Crusader states.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=178}}</ref> From 1265 to 1271, the Mamluk sultan ] drove the Franks to a few small coastal outposts.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tyerman|2006|pp=816–17}}</ref> | ||

| Late 13th-century politics in the Eastern Mediterranean were complex, with a number of powerful interested parties. Baibars had three key objectives: to prevent an alliance between the Latins and the Mongols, to cause dissension between the Mongols particularly between the ] and the Persian ], and to maintain access to a supply of slave recruits from the Russian steppes. In this he developed diplomatic ties with ], supporting him against the Papacy and Louis{{nbsp}}IX's brother ]. The Crusader states were fragmented, and various powers were competing for influence. In the ], Venice drove the Genoese from Acre to Tyre where they continued to trade happily with Baibars' Egypt. Indeed, Baibars negotiated free passage for the Genoese with ], ], the newly restored ruler of Constantinople.<ref>{{harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=628–30}}</ref> | Late 13th-century politics in the Eastern Mediterranean were complex, with a number of powerful interested parties. Baibars had three key objectives: to prevent an alliance between the Latins and the Mongols, to cause dissension between the Mongols (particularly between the ] and the Persian ]), and to maintain access to a supply of slave recruits from the Russian steppes. In this, he developed diplomatic ties with ], supporting him against the Papacy and Louis{{nbsp}}IX's brother ]. The Crusader states were fragmented, and various powers were competing for influence. In the ], Venice drove the Genoese from Acre to Tyre where they continued to trade happily with Baibars' Egypt. Indeed, Baibars negotiated free passage for the Genoese with ], ], the newly restored ruler of Constantinople.<ref>{{harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=628–30}}</ref> | ||

| ] (''Estoire d'Oultre-Mer'', BNF fr. 2825, fol 361v, ca. 1300)]] | ] (''Estoire d'Oultre-Mer'', BNF fr. 2825, fol 361v, ca. 1300)]] | ||

| The French, led by Charles, similarly sought to expand their influence; Charles seized Sicily and Byzantine territory while marrying his daughters to the Latin claimants to Byzantium. To create his own claim to the throne of Jerusalem, Charles executed one rival and purchased the rights to the city from another. In 1270 Charles turned his brother King Louis{{nbsp}}IX's last Crusade, known as the ], to his own advantage by persuading Louis to attack his rebel Arab vassals in ]. Louis' army was devastated by disease, and Louis himself died at Tunis on 25{{nbsp}}August. Louis' fleet returned to France, leaving only ], the future king of England, and a small retinue to continue what is known as the ]. Edward survived an assassination attempt organised by Baibars, negotiated a ten-year truce, and then returned to manage his affairs in England. This ended the last significant crusading effort in the Eastern Mediterranean.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=643–44}}</ref> The ] of a French pope, ], brought the full power of the papacy into line behind Charles. He prepared to launch a crusade against Constantinople but, in what became known as the ], an uprising fomented by Michael{{nbsp}}VIII Palaiologos deprived him of the resources of Sicily, and ] was proclaimed ]. In response, Martin excommunicated Peter and called for an ], which was unsuccessful. In 1285 Charles died, having spent his life trying to amass a Mediterranean empire; he and Louis had viewed themselves as God's instruments to uphold the papacy.<ref>{{Harvnb|Runciman|1958|p=88}}</ref> | The French, led by Charles, similarly sought to expand their influence; Charles seized Sicily and Byzantine territory while marrying his daughters to the Latin claimants to Byzantium. To create his own claim to the throne of Jerusalem, Charles executed one rival and purchased the rights to the city from another. In 1270 Charles turned his brother King Louis{{nbsp}}IX's last Crusade, known as the ], to his own advantage by persuading Louis to attack his rebel Arab vassals in ]. Louis' army was devastated by disease, and Louis himself died at Tunis on 25{{nbsp}}August. Louis' fleet returned to France, leaving only ], the future king of England, and a small retinue to continue what is known as the ]. Edward survived an assassination attempt organised by Baibars, negotiated a ten-year truce, and then returned to manage his affairs in England. This ended the last significant crusading effort in the Eastern Mediterranean.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=643–44}}</ref> The ] of a French pope, ], brought the full power of the papacy into line behind Charles. He prepared to launch a crusade against Constantinople but, in what became known as the ], an uprising fomented by Michael{{nbsp}}VIII Palaiologos deprived him of the resources of Sicily, and ] was proclaimed ]. In response, Martin excommunicated Peter and called for an ], which was unsuccessful. In 1285 Charles died, having spent his life trying to amass a Mediterranean empire; he and Louis had viewed themselves as God's instruments to uphold the papacy.<ref>{{Harvnb|Runciman|1958|p=88}}</ref> | ||

| The causes of the decline in Crusading and the failure of the Crusader States is multi-faceted. Historians have attempted to explain this in terms of Muslim reunification and ] enthusiasm but ], amongst others, considers this too simplistic. Muslim unity was sporadic and the desire for ] ephemeral. The nature of Crusades was unsuited to the conquest and defence of the Holy Land. Crusaders were on a personal pilgrimage and usually returned when it was completed. Although the philosophy of Crusading changed over time, the Crusades continued to provide short-lived armies without centralised leadership led by independently minded potentates. What the Crusader states needed were large standing armies. Religious fervour enabled amazing feats of military endeavour but proved difficult to direct and control. Succession disputes and dynastic rivalries in Europe, failed harvests and heretical outbreaks, all contributed to reducing Latin Europe's concerns for Jerusalem. Ultimately, even though the fighting was also at the edge of the Islamic world, the huge distances made the mounting of Crusades and the maintenance of communications insurmountably difficult. It enabled |

The causes of the decline in Crusading and the failure of the Crusader States is multi-faceted. Historians have attempted to explain this in terms of Muslim reunification and ] enthusiasm but ], amongst others, considers this too simplistic. Muslim unity was sporadic and the desire for ] ephemeral. The nature of Crusades was unsuited to the conquest and defence of the Holy Land. Crusaders were on a personal pilgrimage and usually returned when it was completed. Although the philosophy of Crusading changed over time, the Crusades continued to provide short-lived armies without centralised leadership led by independently minded potentates. What the Crusader states needed were large standing armies. Religious fervour enabled amazing feats of military endeavour but proved difficult to direct and control. Succession disputes and dynastic rivalries in Europe, failed harvests and heretical outbreaks, all contributed to reducing Latin Europe's concerns for Jerusalem. Ultimately, even though the fighting was also at the edge of the Islamic world, the huge distances made the mounting of Crusades and the maintenance of communications insurmountably difficult. It enabled the Islamic world, under the charismatic leadership of Nur al-Din and Saladin, as well as the ruthless Baibars, to use the logistical advantages from proximity to victorious effect.<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge |2012|pp=660–64}}</ref> The mainland ] of the '' ] '' were finally extinguished with the fall of ] in 1289 and ] in 1291.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=122}}</ref> Many Latin Christians were evacuated to Cyprus by boat, were killed or enslaved,<ref>{{Harvnb|Asbridge |2012|p=656}}</ref> however 16th-century Ottoman census records of Byzantine churches show that most parishes remained Christian throughout the Middle Ages.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=131}}</ref> | ||

| ==In Europe== | ==In Europe== | ||

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

| ] in 1491 by ]|alt=Nineteenth century painting of the surrender of Granada]] | ] in 1491 by ]|alt=Nineteenth century painting of the surrender of Granada]] | ||

| The success of the First Crusade led to further and multifaceted crusading in the Middle Ages. The Western Europeans developed a different, overtly spiritual, perception of the reconquest of the ]. Other conflicts began to be seen as Crusades |

The success of the First Crusade led to further and multifaceted crusading in the Middle Ages. The Western Europeans developed a different, overtly spiritual, perception of the reconquest of the ]. Other conflicts began to be seen as Crusades with Crusading privileges and legal frameworks applied. These conflicts, outside the Holy Land, included the territorial wars in the Baltic, the Popes' wars against their political enemies in Italy and, after the Fourth Crusade, the defence of the Latin Empire of Constantinople.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=182}}</ref> | ||

| At the time of the First Crusade, Spain was the only example of Latin Christians subjugated by the Islamic World. The period of conquest was over by c. 900 and in 1031 the collapse of the ] created the political conditions that would make the Reconquista possible. The Christian powers—], ], ] and ]—were essentially geo-political constructs with no history based on tribe or ethnicity. Although small, all had developed a military aristocracy and technique.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=183–84}}</ref> By the time of the Second Crusade three kingdoms had developed enough to represent Christian expansion{{mdash}}], Aragon and ]. A consensus has emerged among modern historians against the view of a generation of Spanish scholars who believed it was Spanish religious and national destiny to defeat Islam.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=188}}</ref> In 1123 ] issued a Bull creating an equivalence between the Reconquista and Crusading in the East against Muslims. However, it was the Second Crusade that placed it within the context of Crusading. ] followed naming Iberia as a target, the Genoese provided logistic support, a mixed band of Crusaders captured ] and Bernard of Clairveaux preached for the campaign in the same terms as he did against the Wends of Denmark.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=190}}</ref> The ] was won in 1212 with the support of 70,000 non-Spanish combatants responding to a crusade preached by ]. However, many of these deserted because of the toleration the Spanish demonstrated to the defeated Muslims. For the Spanish, The Reconquista was a war of domination rather than extinction.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=191}}</ref> This contrasted with the treatment of the native Christians, the ]. The ] was relentlessly imposed and the native Christians were absorbed into mainstream the Roman church by the ], ] clerical appointments and the Military Orders.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=131}}</ref> The Reconquista was not immediately completed and continued to attract crusaders and crusader privileges until ] was suppressed in the Fourteenth century.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=192}}</ref> The ] held out until 1492, at which point the Muslims and Jews were finally expelled from the peninsula.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=211}}</ref> | At the time of the First Crusade, Spain was the only example of Latin Christians subjugated by the Islamic World. The period of conquest was over by c. 900 and in 1031 the collapse of the ] created the political conditions that would make the Reconquista possible. The Christian powers—], ], ] and ]—were essentially geo-political constructs with no history based on tribe or ethnicity. Although small, all had developed a military aristocracy and technique.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|pp=183–84}}</ref> By the time of the Second Crusade three kingdoms had developed enough to represent Christian expansion{{mdash}}], Aragon and ]. A consensus has emerged among modern historians against the view of a generation of Spanish scholars who believed it was Spanish religious and national destiny to defeat Islam.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=188}}</ref> In 1123 ] issued a Bull creating an equivalence between the Reconquista and Crusading in the East against Muslims. However, it was the Second Crusade that placed it within the context of Crusading. ] followed naming Iberia as a target, the Genoese provided logistic support, a mixed band of Crusaders captured ] and Bernard of Clairveaux preached for the campaign in the same terms as he did against the Wends of Denmark.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=190}}</ref> The ] was won in 1212 with the support of 70,000 non-Spanish combatants responding to a crusade preached by ]. However, many of these deserted because of the toleration the Spanish demonstrated to the defeated Muslims. For the Spanish, The Reconquista was a war of domination rather than extinction.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=191}}</ref> This contrasted with the treatment of the native Christians, the ]. The ] was relentlessly imposed and the native Christians were absorbed into mainstream the Roman church by the ], ] clerical appointments and the Military Orders.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=131}}</ref> The Reconquista was not immediately completed and continued to attract crusaders and crusader privileges until ] was suppressed in the Fourteenth century.<ref>{{Harvnb|Jotischky|2004|p=192}}</ref> The ] held out until 1492, at which point the Muslims and Jews were finally expelled from the peninsula.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=211}}</ref> | ||

| ===Northern European Crusades=== | ===Northern European Crusades=== | ||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

| {{Main|Northern Crusades|Wendish Crusade|Livonian Crusade|Prussian Crusade|Swedish Crusades (disambiguation)}} | {{Main|Northern Crusades|Wendish Crusade|Livonian Crusade|Prussian Crusade|Swedish Crusades (disambiguation)}} | ||

| ] in Europe around 1300 from the 2008 exhibition at the ], Switzerland ("The Crusades – A Search for Clues: The Orders of Chivalry in Switzerland". Shaded area is sovereign territory, Grand Master HQ in Venice is highlighted)|alt=Map of the branches of the Teutonic Order in Europe around 1300 showing sovereign territory in the Baltic and the Grand Master's HQ in Venice]] | ] in Europe around 1300 from the 2008 exhibition at the ], Switzerland ("The Crusades – A Search for Clues: The Orders of Chivalry in Switzerland". Shaded area is sovereign territory, Grand Master HQ in Venice is highlighted)|alt=Map of the branches of the Teutonic Order in Europe around 1300 showing sovereign territory in the Baltic and the Grand Master's HQ in Venice]] | ||

| The success of the First Crusade inspired 12th-century popes such as ], ], ], and ] to call for military campaigns with the aim of ] the more remote regions of northern and north-eastern Europe. These campaigns are known as the ].<ref name="Davies 1997 362">{{Harvnb|Davies|1997|p=362}}</ref> The Wendish Crusade of 1147 saw ], ], and ] attempt to forcibly convert the tribes of ] and ], who were ] or "Wends". Celestine{{nbsp}}III called for a Crusade in 1193, but when Bishop ] responded in 1198, he led a large army into defeat and to his death. In response, Innocent{{nbsp}}III issued a ] declaring a Crusade, and ], Bishop of ], along with the ] brought all of the north-east ] under Catholic control.<ref name="Davies 1997 362"/> ] gave ] to the Teutonic Knights in 1226 as a base for a Crusade against the local Polish princes.<ref name="Davies 1997 362"/><ref name="Lock 2006 96">{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=96}}</ref> The Livonian Brothers of the Sword were defeated by the Lithuanians, so in 1237 Gregory{{nbsp}}IX merged the remainder of the order into the Teutonic Order as the ].<ref name="Lock 2006 103">{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=103}}</ref> By the middle of the century, the Teutonic Knights completed their conquest of the Prussians before conquering and converting the Lithuanians in the subsequent decades.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=221–22}}</ref> The order also came into conflict with the Eastern Orthodox Church of the ] and ]s. In 1240 the Orthodox Novgorod army defeated the Catholic Swedes in the ], and, two years later, they defeated the Livonian Order in the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=104, 221}}</ref> | The success of the First Crusade inspired 12th-century popes such as ], ], ], and ] to call for military campaigns with the aim of ] the more remote regions of northern and north-eastern Europe. These campaigns are known as the ].<ref name="Davies 1997 362">{{Harvnb|Davies|1997|p=362}}</ref> The Wendish Crusade of 1147 saw ], ], and ] attempt to forcibly convert the tribes of ] and ], who were ] or "Wends". Celestine{{nbsp}}III called for a Crusade in 1193, but when Bishop ] responded in 1198, he led a large army into defeat and to his death. In response, Innocent{{nbsp}}III issued a ] declaring a Crusade, and ], Bishop of ], along with the ] brought all of the north-east ] under Catholic control.<ref name="Davies 1997 362"/> Polish Duke ] gave ] to the Teutonic Knights in 1226 as a base for a Crusade against the local Polish princes.<ref name="Davies 1997 362"/><ref name="Lock 2006 96">{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=96}}</ref> The Livonian Brothers of the Sword were defeated by the Lithuanians, so in 1237 Gregory{{nbsp}}IX merged the remainder of the order into the Teutonic Order as the ].<ref name="Lock 2006 103">{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=103}}</ref> By the middle of the century, the Teutonic Knights completed their conquest of the Prussians before conquering and converting the Lithuanians in the subsequent decades.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=221–22}}</ref> The order also came into conflict with the Eastern Orthodox Church of the ] and ]s. In 1240 the Orthodox Novgorod army defeated the Catholic Swedes in the ], and, two years later, they defeated the Livonian Order in the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=104, 221}}</ref> | ||

| ===Crusade against heresy=== | ===Crusade against heresy=== | ||

| Line 128: | Line 128: | ||

| ] in a miniature by ] titled ''Les Passages d'Outremer'', ] Fr 5594, c.{{nbsp}}1475 |alt=Image of Battle of Nicopolis]] | ] in a miniature by ] titled ''Les Passages d'Outremer'', ] Fr 5594, c.{{nbsp}}1475 |alt=Image of Battle of Nicopolis]] | ||

| Minor Crusading efforts lingered into the 14th{{nbsp}}century, and several Crusades were launched during the 14th and 15th centuries to counter the expansion of the ]. In 1309 as many as 30,000 peasants gathered from England, north-eastern France, and Germany proceeded as far as ] but disbanded there.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=187–88}}</ref> ] captured and sacked ] in 1365 in what became known as the ]; his motivation was as much commercial as religious.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=195–96}}</ref> ] led the 1390 ] against Muslim ]s in North Africa; after a ten-week siege, the Crusaders signed a ten-year truce.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=199}}</ref> | Minor Crusading efforts lingered into the 14th{{nbsp}}century, and several Crusades were launched during the 14th and 15th centuries to counter the expansion of the ]. In 1309 as many as 30,000 peasants gathered from England, north-eastern France, and Germany proceeded as far as ] but disbanded there.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=187–88}}</ref> King ] captured and sacked ] in 1365 in what became known as the ]; his motivation was as much commercial as religious.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=195–96}}</ref> ] led the 1390 ] against Muslim ]s in North Africa; after a ten-week siege, the Crusaders signed a ten-year truce.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=199}}</ref> | ||

| The Ottomans had conquered most of the ] and reduced Byzantine influence to the area immediately surrounding ] after victory at the ] in 1389. Nicopolis was seized from the ]n Tsar ] in 1393 and a year later ] proclaimed a new Crusade against the Turks, although the ] had split the papacy.<ref name="Davies 1997 448">{{Harvnb|Davies|1997|p=448}}</ref> This Crusade was led by ], King of Hungary; many French nobles joined Sigismund's forces, including the Crusade's military leader, ] (son of the Duke of Burgundy). Sigismund advised the Crusaders to adopt a cautious, more defensive strategy, when they reached the Danube, instead they besieged the city of ]. The Ottomans defeated them in the ] on 25{{nbsp}}September, capturing 3,000 prisoners.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=200}}</ref> | The Ottomans had conquered most of the ] and reduced Byzantine influence to the area immediately surrounding ] after victory at the ] in 1389. Nicopolis was seized from the ]n Tsar ] in 1393 and a year later ] proclaimed a new Crusade against the Turks, although the ] had split the papacy.<ref name="Davies 1997 448">{{Harvnb|Davies|1997|p=448}}</ref> This Crusade was led by ], King of Hungary; many French nobles joined Sigismund's forces, including the Crusade's military leader, ] (son of the Duke of Burgundy). Sigismund advised the Crusaders to adopt a cautious, more defensive strategy, when they reached the Danube, instead they besieged the city of ]. The Ottomans defeated them in the ] on 25{{nbsp}}September, capturing 3,000 prisoners.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=200}}</ref> | ||

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

| The ], also known as the Hussite Crusade, involved military action against the ] in the ] and the followers of early Czech ] ], who was ] in 1415. Crusades were declared five times during that period: in 1420, 1421, 1422, 1427, and 1431. These expeditions forced the Hussite forces, who disagreed on many doctrinal points, to unite to drive out the invaders. The wars ended in 1436 with the ratification of the compromise ] by the Church and the Hussites.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=201–02}}</ref> | The ], also known as the Hussite Crusade, involved military action against the ] in the ] and the followers of early Czech ] ], who was ] in 1415. Crusades were declared five times during that period: in 1420, 1421, 1422, 1427, and 1431. These expeditions forced the Hussite forces, who disagreed on many doctrinal points, to unite to drive out the invaders. The wars ended in 1436 with the ratification of the compromise ] by the Church and the Hussites.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=201–02}}</ref> | ||

| As the Ottomans pressed westward, Sultan ] destroyed the last ] at ] on the ] in 1444 and four years later crushed the last Hungarian expedition.<ref name="Davies 1997 448"/> In 1453 they extinguished most of the remains of the Byzantine Empire with the ]. ] and ] organised a 1456 Crusade to oppose the Ottoman Empire and lift |

As the Ottomans pressed westward, Sultan ] destroyed the last ] at ] on the ] in 1444 and four years later crushed the last Hungarian expedition.<ref name="Davies 1997 448"/> In 1453 they extinguished most of the remains of the Byzantine Empire with the ]. ], a Hungarian general, and the Franciscan friar] organised a 1456 Crusade to oppose the Ottoman Empire and lift the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|pp=202–03}}</ref> ], the future Pope Pius II, and ], the future Saint John of Capistrano, preached the Crusade. The princes of the Holy Roman Empire in the Diets of Ratisbon and Frankfurt promised assistance, and a league was formed between Venice, Florence, and Milan, but eventually nothing came of it. In April 1487 ] called for a Crusade against the ] of ], the ], and the ] in southern France and northern Italy because they were unorthodox and heretical. The only efforts undertaken were in the Dauphiné, resulting in little change.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lock|2006|p=204}}</ref> Venice was the only polity to continue to pose a significant threat to the Ottomans in the Mediterranean, but it pursued the "Crusade" mostly for its commercial interests, leading to the protracted ], which continued, with interruptions, until 1718. The end of the Crusading in terms of at least nominal efforts by Catholic Europe against Muslim incursion, came in the 16th{{nbsp}}century, when the Franco-Imperial wars assumed continental proportions. King ] sought allies from all quarters, including from German Protestant princes and Muslims. Amongst these, he entered into one of the ] with Ottoman Sultan ] while making common cause with ], an Ottoman admiral, and a number of the Sultan's North African vassals.<ref>{{Harvnb|Davies|1997|pp=544–45}}</ref> | ||

| ==Crusader states== | ==Crusader states== | ||

| Line 161: | Line 161: | ||

| The Crusaders' mentality to imitate the customs from their Western European homelands meant that there were very few innovations developed from the culture of the crusader states. Three notable exceptions to this rule are the military orders, warfare and fortifications.<ref>{{harvnb| Prawer|2001| p=252}}</ref> The Hospitallers (Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem) were founded in Jerusalem before the First Crusade but added a martial element to its ongoing medical functions to become a much larger military order.<ref>{{harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=169}}</ref> In this way the knighthood entered the previously monastic and ecclesiastical sphere.<ref>{{harvnb| Prawer|2001| p=253}}</ref> | The Crusaders' mentality to imitate the customs from their Western European homelands meant that there were very few innovations developed from the culture of the crusader states. Three notable exceptions to this rule are the military orders, warfare and fortifications.<ref>{{harvnb| Prawer|2001| p=252}}</ref> The Hospitallers (Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem) were founded in Jerusalem before the First Crusade but added a martial element to its ongoing medical functions to become a much larger military order.<ref>{{harvnb|Asbridge|2012|p=169}}</ref> In this way the knighthood entered the previously monastic and ecclesiastical sphere.<ref>{{harvnb| Prawer|2001| p=253}}</ref> | ||

| The military orders such as the ] and the ] provided Latin Christendom's first professional armies in support of the ] and the other Crusader states. The Poor Knights of Christ (Templars) and their ] were founded around 1119 by a small band of knights who dedicated themselves to protecting pilgrims en{{nbsp}}route to Jerusalem.<ref>{{harvnb| Asbridge|2012| p= 168}}</ref> The Hospitallers and the Templars became supranational organisations as Papal support led to rich donations of land and revenue across Europe. This in turn led to a steady flow of new recruits and the wealth to maintain multiple fortifications across the Outremer. In time, this developed into autonomous power in the region.<ref>{{harvnb| Asbridge|2012|pp=169–70}}</ref> After the fall of Acre the Hospitallers first relocated to Cyprus, then conquered and ruled Rhodes (1309–1522) and Malta (1530–1798), and continue in existence to the present day. ] probably had financial and political reasons to oppose the Knights Templar, which led to him exerting pressure on ]. The Pope responded in 1312, with a series of papal bulls including '']'' and '']'' that dissolved the order on the alleged and probably false grounds of sodomy, magic, and heresy.<ref name="Davies 1997 359">{{Harvnb|Davies|1997|p=359}}</ref> | The military orders such as the ] and the ] provided Latin Christendom's first professional armies in support of the ] and the other Crusader states. The Poor Knights of Christ (Templars) and their ] were founded around 1119 by a small band of knights who dedicated themselves to protecting pilgrims en{{nbsp}}route to Jerusalem.<ref>{{harvnb| Asbridge|2012| p= 168}}</ref> The Hospitallers and the Templars became supranational organisations as Papal support led to rich donations of land and revenue across Europe. This in turn led to a steady flow of new recruits and the wealth to maintain multiple fortifications across the Outremer. In time, this developed into autonomous power in the region.<ref>{{harvnb| Asbridge|2012|pp=169–70}}</ref> After the fall of Acre the Hospitallers first relocated to Cyprus, then conquered and ruled Rhodes (1309–1522) and Malta (1530–1798), and continue in existence to the present day. King ] probably had financial and political reasons to oppose the Knights Templar, which led to him exerting pressure on ]. The Pope responded in 1312, with a series of papal bulls including '']'' and '']'' that dissolved the order on the alleged and probably false grounds of sodomy, magic, and heresy.<ref name="Davies 1997 359">{{Harvnb|Davies|1997|p=359}}</ref> | ||

| ==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

Revision as of 20:36, 18 June 2019

For other uses, see Crusade (disambiguation) and Crusader (disambiguation).

| Crusades | |

|---|---|

| Ideology and institutions

In the Holy Land (1095–1291)

Later Crusades (1291–1717)

Northern (1147–1410) Against Christians (1204–1588) Popular (1096–1320) Reconquista (722–1492) |

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Christianity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

||||

| Theology | ||||

|

||||

| Related topics | ||||

The Crusades were a series of religious wars sanctioned by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The most commonly known Crusades are the campaigns in the Eastern Mediterranean aimed at recovering the Holy Land from Muslim rule, but the term "Crusades" is also applied to other church-sanctioned campaigns. These were fought for a variety of reasons including the suppression of paganism and heresy, the resolution of conflict among rival Roman Catholic groups, or for political and territorial advantage. At the time of the early Crusades the word did not exist, only becoming the leading descriptive term around 1760.

In 1095, Pope Urban II called for the First Crusade in a sermon at the Council of Clermont. He encouraged military support for the Byzantine Empire and its Emperor, Alexios I, who needed reinforcements for his conflict with westward migrating Turks colonizing Anatolia. One of Urban's aims was to guarantee pilgrims access to the Eastern Mediterranean holy sites that were under Muslim control but scholars disagree as to whether this was the primary motive for Urban or those who heeded his call. Urban's strategy may have been to unite the Eastern and Western branches of Christendom, which had been divided since the East–West Schism of 1054 and to establish himself as head of the unified Church. The initial success of the Crusade established the first four Crusader states in the Eastern Mediterranean: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the County of Tripoli. The enthusiastic response to Urban's preaching from all classes in Western Europe established a precedent for other Crusades. Volunteers became Crusaders by taking a public vow and receiving plenary indulgences from the Church. Some were hoping for a mass ascension into heaven at Jerusalem or God's forgiveness for all their sins. Others participated to satisfy feudal obligations, obtain glory and honour or to seek economic and political gain.