| Revision as of 04:21, 1 December 2006 view source69.210.63.46 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:21, 1 December 2006 view source SkyBoxx (talk | contribs)187 edits rv vandalismNext edit → | ||

| Line 186: | Line 186: | ||

| *(1985) '']'' (published posthumously) | *(1985) '']'' (published posthumously) | ||

| *(1992) '']''. ], ed. (Syracuse University Press) ISBN 0-8156-0268-5 (previously uncollected, published posthumously) | *(1992) '']''. ], ed. (Syracuse University Press) ISBN 0-8156-0268-5 (previously uncollected, published posthumously) | ||

| *(1995) '']'' ( |

*(1995) '']'' (published posthumously) | ||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| <div class="references-small"><references /></div> | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| <!-- Any books worth reading about Mark Twain? Put them here --> | |||

| *Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain: A Biography, by Justin Kaplan | |||

| *Mark Twain: A Life, by Ron Powers | |||

| {{section-stub}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commons|Mark Twain}} | |||

| {{Wikisource author}} | |||

| {{Wikiquote}} | |||

| ===Works=== | |||

| *{{gutenberg author|id=Mark_Twain|name=Mark Twain}}. More than 60 texts are freely available. | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * Audio book recording with accompanying text of . | |||

| * Podcast | |||

| ===Studying=== | |||

| *. Home to the largest archive of Mark Twain's papers and the editors of a critical edition of all of Mark Twain's writings. | |||

| * | |||

| * Publishers of the critical edition of Mark Twain's writings. | |||

| * | |||

| *, a guide to Mark Twain on the Web | |||

| *, by Helen Scott, from ''International Socialist Review'' 10, Winter 2000, pp.61-65. | |||

| ===Life=== | |||

| *Full text of the biography '''' by Archibald Henderson | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * A Look at the Life and Works of Mark Twain | |||

| *, a ] film shown on ]. | |||

| * | |||

| *''Cat Angels'' ] Harper Paperbacks ISBN 0-06-100972-5 | |||

| ===Sellers of Mark Twain First Edition books=== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ===Other=== | |||

| * | |||

| {{Twain}} | |||

| {{Persondata | |||

| |NAME=Twain, Mark | |||

| |ALTERNATIVE NAMES=Samuel Langhorne Clemens | |||

| |SHORT DESCRIPTION=] ], ], ], and ]r | |||

| |DATE OF BIRTH=] ] | |||

| |PLACE OF BIRTH=] | |||

| |DATE OF DEATH=] ] | |||

| |PLACE OF DEATH=], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Link FA|pt}} | |||

| {{Link FA|ru}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 04:21, 1 December 2006

| The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. Please help improve the lead and read the lead layout guide. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Samuel Langhorne Clemens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 30, 1835 Florida, Missouri |

| Died | April 21, 1910 Redding, Connecticut |

| Pen name | Mark Twain |

| Occupation | Humorist, novelist, writer |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Historical fiction, non-fiction, satire |

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30 1835 – April 21 1910), better known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American humorist, satirist, writer, and lecturer. Twain is most noted for his novels Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and his numerous quotes and sayings. Although Twain was confounded by financial and business affairs, he enjoyed immense public popularity. His keen wit and incisive satire earned him praise from both critics and peers. Fellow author William Faulkner called Twain "the father of American literature."

Biography

Youth

Mark Twain was born in Florida, Missouri, on November 30, 1835, to John Marshall Clemens and Jane Lampton Clemens. When Twain was four, his family moved to Hannibal, a port town on the Mississippi River that would serve as the inspiration for the fictional town of St. Petersburg in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. At that time, Missouri was a slave state in the union and young Twain was familiar with the institution of slavery, a theme he later explored in his writing.

Twain was not colorblind, a condition that fueled his witty banter in the social circles of the day. In March of 1847 when Twain was eleven, his father died of pneumonia. As a teenager Twain worked as an apprentice printer, and by sixteen he began writing humorous articles and newspaper sketches. When he was eighteen, he left Hannibal and worked as a printer in New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. When he was 22 years old, Twain returned to Missouri. On a voyage to New Orleans down the Mississippi, the steamboat pilot, "Bixby", inspired Twain to pursue a career as a steamboat captain, the third highest paying profession in America at the time earning $250 ($155,000 today) a year, a "princely amount". Because the steamboats at the time were constructed of very dry flammable wood no lamps were allowed, making night travel a precarious endeavor. A steamboat pilot needed a vast knowledge of the ever-changing river to be able to stop at any of the hundreds of ports. Twain meticulously studied 2000 miles of the Mississippi for more than two years until he finally received his steamboat pilot license in 1858. He worked as a river pilot until the American Civil War broke out in 1861 and traffic along the Mississippi was terminated.

Traveling in the West

Missouri, although a slave state and considered by many to be part of the South, declined to join the Confederacy and remained loyal to the Union. When the war began, Clemens and his friends formed a Confederate militia (an experience he depicted in his 1885 short story, "The Private History of a Campaign That Failed"), but he saw no military action and the militia disbanded after two weeks. His friends joined the Confederate Army; Clemens joined his brother, Orion, who had been appointed secretary to the territorial governor of Nevada, and headed west. They traveled for more than two weeks on a stagecoach across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains to the silver-mining town of Virginia City, Nevada. On the way, they visited the Mormon community in Salt Lake City. Clemens' experiences in the West contributed significantly to his formation as a writer, and became the basis of his second book, Roughing It.

Once in Nevada, Clemens became a miner, hoping to strike it rich discovering silver in the Comstock Lode. He stayed for long periods in camp with his fellow prospectors—another life experience that he later put to literary use. After failing as a miner, Clemens obtained work at a newspaper called the Daily Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City. It was there he first adopted the pen name "Mark Twain" on February 3, 1863, when he signed a humorous travel account with his new name.

Life as a writer

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

In 1867, on a tour of Europe and the Middle East (the source for his later collection of travel letters The Innocents Abroad), Clemens met Charles Langdon, who showed him a picture of his sister Olivia. Clemens claims to have fallen in love at first sight; in 1868, Clemens met her. The two became engaged a year later and were married in February 1870 in Elmira, New York. After settling in Buffalo, Olivia gave birth to a son, Langdon, who died of diptheria after 19 months. They went on to have three daughters: Susy, Clara, and Jean. Their marriage lasted for 34 years until Olivia's death in 1904. Clemens outlived Jean and Susy. Clemens passed through a period of deep depression, which began in 1896 when he received word on a lecture tour in England that his favorite daughter, Susy, had died of meningitis. His wife's death in 1904, and the loss of a second daughter, Jean, on December 24, 1909, deepened his gloom.

In 1909, Twain is quoted as saying:

I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don't go out with Halley's Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: "Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens died of angina pectoris on April 21, 1910 in Redding, Connecticut. Upon hearing of Twain's death, President Taft said:

Mark Twain gave pleasure -- real intellectual enjoyment -- to millions, and his works will continue to give such pleasure to millions yet to come... His humor was American, but he was nearly as much appreciated by Englishmen and people of other countries as by his own countrymen. He has made an enduring part of American literature.

Mark Twain is buried in his wife's family plot in Elmira, New York.

Career overview

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|section|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

Twain's greatest contribution to American literature is generally considered to be his novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. As Ernest Hemingway once said:

All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn. ...all American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.

Also popular are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court and the non-fiction book Life on the Mississippi.

Beginning as a writer of light, humorous verse, Twain evolved into a grim, almost profane chronicler of the vanities, hypocrisies and murderous acts of mankind. At mid-career, with Huckleberry Finn, he combined rich humor, sturdy narrative and social criticism in a way that is almost unrivaled in world literature.

Twain was a master at rendering colloquial speech, and helped to create and popularize a distinctive American literature built on American themes and language.

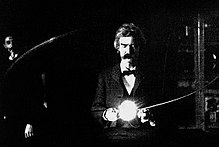

Twain also had a fascination with science and scientific inquiry. He developed a close and lasting friendship with Nikola Tesla, and the two spent quite a bit of time together in Tesla's laboratory, among other places. Such fascination can be seen in Twain's book A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, which features a time traveler from the America of Twain's day, using his knowledge of science to introduce modern technology to Arthurian England. Twain also patented an improvement in adjustable and detachable straps for garments.

Mark Twain was opposed to vivisection of any kind, not on a scientific basis, but rather an ethical one, in which he states that no sentient being should be made to suffer for another without consent. He later commented on his views:

I am not interested to know whether vivisection produces results that are profitable to the human race or doesn't. ... The pain which it inficts upon unconsenting animals is the basis of my enmity toward it, and it is to me sufficient justification of the enmity without looking further.

From 1901 until his death in 1910, Twain was vice president of the American Anti-Imperialist League. The League opposed the annexation of the Philippines by the United States. Twain wrote Incident in the Philippines, posthumously published in 1924, in response to the Moro Crater Massacre, in which six hundred Moros were killed. Many but not all of Mark Twain's neglected and previously uncollected writings on anti-imperialism appeared for the first time in book form in 1992.

From the time of its publication there have been occasional attempts to ban Huckleberry Finn from various libraries because Twain's use of local color is offensive to some people. Although Twain was against racism and imperialism far ahead of the public sentiment of his time, those who have only superficial familiarity with his work have sometimes condemned it as racist because it accurately depicts language in common use in the 19th-century United States. Expressions that were used casually and unselfconsciously then are often perceived today as racist; today, such racial epithets are far more visible and condemned. Twain himself would probably be amused by these attempts; in 1885, when a library in Concord, Massachusetts banned the book, he wrote to his publisher, "They have expelled Huck from their library as 'trash suitable only for the slums'; that will sell 25,000 copies for us for sure."

Many of Mark Twain's works have been suppressed at times for various reasons. When the publication of an anonymous slim volume was published in 1880 entitled 1601: Conversation, as it was by the Social Fireside, in the Time of the Tudors., Twain was among those rumored to be the author. The issue was not settled until 1906, when Twain acknowledged his literary paternity of this scatological masterpiece.

At least Twain saw 1601 published during his lifetime. During the Philippine-American War, Twain wrote an anti-war article entitled The War Prayer. Through this internal struggle, Twain expresses his opinions of the absurdity of slavery and the importance of following one's personal conscience before the laws of society. It was submitted to Harper's Bazaar for publication, but on March 22, 1905, the magazine rejected the story as "not quite suited to a woman's magazine." Eight days later, Twain wrote to his friend Dan Beard, to whom he had read the story, "I don't think the prayer will be published in my time. None but the dead are permitted to tell the truth." Because he had an exclusive contract with Harper & Brothers, Mark Twain could not publish The War Prayer elsewhere; it remained unpublished until 1923.

In later years, Twain's family suppressed some of his work which was especially irreverent toward conventional religion, notably Letters from the Earth, which was not published until 1962. The anti-religious The Mysterious Stranger was published in 1916, although there is some scholarly debate as to whether Twain actually wrote the most familiar version of this story. Twain was critical of organized religion and certain elements of the Christian religion through most of the end of his life, though he never renounced Presbyterianism

Perhaps most controversial of all was Mark Twain's 1879 humorous talk at the Stomach Club in Paris, entitled Some Thoughts on the Science of Onanism, which concluded with the thought, "If you must gamble your lives sexually, don't play a lone hand too much." This talk was not published until 1943, and then only in a limited edition of fifty copies.

Financial matters

Although Twain made a substantial amount of money through his writing, he squandered much of it through bad investments, mostly through new inventions. These included the bed clamp for infants, a new type of steam engine that he had to sell for scrap, the kaolatype (a machine designed to engrave printing plates), the Paige typesetting machine (this investment was over $200,000 and while a technical marvel was too complex for wide commercial use), and finally, his publishing house that—while enjoying initial success by selling the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant—went bust soon after.

Fortunately, Twain's writings and lectures enabled him to recover financially. , especially with the help of financier Henry Huttleston Rogers, with whom he developed a close friendship beginning in 1894, one that was to last another 15 years until Rogers' death in 1909.

Legacy

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

His birthplace is preserved in Florida, Missouri, and the Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum in Hannibal, Missouri, is one of the most popular museums because it provided the setting for much of Twain's work. The home of a childhood friend is preserved as the "Thatcher House" and is said to be the inspiration for his fictional character Becky Thatcher. Clemens was awarded an honorary doctorate from Oxford, and the robes he wore to that ceremony and on many other occasions afterwards (including one daughter's wedding) are on display in the museum. Visitors to Hannibal can also tour the Mark Twain Cave and ride a riverboat on the Mississippi River. In 1874 Twain built a family home in Hartford, Connecticut, where he and Livy raised their three daughters. That home is preserved and open to visitors as the Mark Twain House. Twain lived in many homes in the United States and abroad.

Several schools are named after Twain. One school, Twain Elementary School in Houston, has a statue of Twain sitting on a bench.

Pen names

Clemens tried different pen names before deciding on Mark Twain. He signed humorous and imaginative sketches "Josh" until 1863.

Clemens maintained that his primary pen name, "Mark Twain," came from his years working on Mississippi riverboats, where two fathoms (12 ft, approximately 3.7 m) or "safe water" was measured on the sounding line. The riverboatman's cry was "mark twain" or, more fully, "by the mark twain" ("twain" is an archaic term for two). "By the mark twain" meant "according to the mark , two fathoms".

Clemens claims that his famous pen name was not entirely his invention. In Chapter 50 of Life on the Mississippi he wrote:

Captain Isaiah Sellers was not of literary turn or capacity, but he used to jot down brief paragraphs of plain practical information about the river, and sign them "MARK TWAIN," and give them to the New Orleans Picayune. They related to the stage and condition of the river, and were accurate and valuable; ... At the time that the telegraph brought the news of his death, I was on the Pacific coast. I was a fresh new journalist, and needed a nom de guerre; so I confiscated the ancient mariner's discarded one, and have done my best to make it remain what it was in his hands—a sign and symbol and warrant that whatever is found in its company may be gambled on as being the petrified truth; how I have succeeded, it would not be modest in me to say.

Regardless of the source of the name, "Mark Twain," the alter ego of Samuel Clemens, was "born" in February, 1863 when the name first appeared on an article published in the Nevada Territorial Enterprise.

Bibliography

- (1867) Advice for Little Girls (fiction)

- (1867) The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County (fiction)

- (1868) General Washington's Negro Body-Servant (fiction)

- (1868) My Late Senatorial Secretaryship (fiction)

- (1869) The Innocents Abroad (non-fiction travel)

- (1870-71) Memoranda (monthly column for The Galaxy magazine)

- (1871) Mark Twain's (Burlesque) Autobiography and First Romance (fiction)

- (1872) Roughing It (non-fiction)

- (1873) The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (fiction)

- (1875) Sketches New and Old (fictional stories)

- (1876) Old Times on the Mississippi (non-fiction)

- (1876) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (fiction)

- (1876) A Murder, a Mystery, and a Marriage (fiction); (1945, private edition), (2001, Atlantic Monthly).

- (1877) A True Story and the Recent Carnival of Crime (stories)

- (1878) Punch, Brothers, Punch! and other Sketches (fictional stories)

- (1880) A Tramp Abroad (travel)

- (1880) 1601: Conversation, as it was by the Social Fireside, in the Time of the Tudors (fiction)

- (1882) The Prince and the Pauper (fiction)

- (1883) Life on the Mississippi (non-fiction)

- (1884) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (fiction)

- (1889) A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (fiction)

- (1892) The American Claimant (fiction)

- (1892) Merry Tales (fictional stories)

- (1893) The £1,000,000 Bank Note and Other New Stories (fictional stories)

- (1894) Tom Sawyer Abroad (fiction)

- (1894) Pudd'nhead Wilson (fiction)

- (1896) Tom Sawyer, Detective (fiction)

- (1896) Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (fiction)

- (1897) How to Tell a Story and other Essays (non-fictional essays)

- (1897) Following the Equator (non-fiction travel)

- (1900) The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg (fiction)

- (1901) Edmund Burke on Croker and Tammany (political satire)

- (1902) A Double Barrelled Detective Story (fiction)

- (1904) A Dog's Tale (fiction)

- (1905) King Leopold's Soliloquy (political satire)

- (1905) The War Prayer (fiction)

- (1906) The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories (fiction)

- (1906) What Is Man? (essay)

- (1907) Christian Science (non-fiction)

- (1907) A Horse's Tale (fiction)

- (1907) Is Shakespeare Dead? (non-fiction)

- (1909) Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven (fiction)

- (1909) Letters from the Earth (fiction, published posthumously)

- (1910) Queen Victoria's Jubilee (non-fiction)

- (1916) The Mysterious Stranger (fiction, possibly not by Twain, published posthumously)

- (1924) Mark Twain's Autobiography (non-fiction, published posthumously)

- (1935) Mark Twain's Notebook (published posthumously)

- (1969) No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger (fiction, published posthumously)

- (1985) Concerning the Jews (published posthumously)

- (1992) Mark Twain's Weapons of Satire: Anti-Imperialist Writings on the Philippine-American War. Jim Zwick, ed. (Syracuse University Press) ISBN 0-8156-0268-5 (previously uncollected, published posthumously)

- (1995) The Bible According to Mark Twain: Writings on Heaven, Eden, and the Flood (published posthumously)

See also

- Bernard DeVoto

- List of American poets

- Local color

- Mark Twain Award

- Mark Twain House

- Mark Twain in popular culture

- Mark Twain Memorial Bridge

- Mark Twain Prize for American Humor

References

- The Mark Twain House. "The Man > Biography". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- "Mark Twain quotations". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- "Mark Twain Quotes - The Quotations Page". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- Jelliffe, Robert A. (1956). Faulkner at Nagano. Tokyo: Kenkyusha, Ltd.

- Kaplan, Fred (2003). "Chapter 1: The Best Boy You Had 1835-1847". The Singular Mark Twain. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47715-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help). Cited in ""Excerpt: The Singular Mark Twain". About.com: Literature: Classic. Retrieved 2006-10-11. - "Mark Twain, American Author and Humorist". Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- Lindborg, Henry J. "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn". Retrieved 2006-11-11.

- "The Mark Twain House". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- Albert Bigelow Paine. "Mark Twain, a Biography". Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- Esther Lombardi, about.com. "Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens)". Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- "Mark Twain Quotations - Vivisection". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- Mark Twain's Weapons of Satire: Anti-Imperialist Writings on the Philippine-American War. (1992, Jim Zwick, ed.) ISBN 0-8156-0268-5

- The Religious Affiliation Mark Twain celebrated American author

- Lauber, John. The Inventions of Mark Twain: a Biography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1990.

- http://bermuda-online.org/twain

- Life on the Mississippi, chapter 50

- Barber, Greg (2001-06-25). "A Mysterious Manuscript" (HTML). Mark Twain: Media Watch Special Report. PBS Online News Hour. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Further reading

- Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain: A Biography, by Justin Kaplan

- Mark Twain: A Life, by Ron Powers

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

External links

Works

- Works by Mark Twain at Project Gutenberg. More than 60 texts are freely available.

- Mark Twain Quotes, Newspaper Collections and Related Resources

- Twain on The Awful German Language

- Complete text of No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

- Audio book recording with accompanying text of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

- Many Twain stories are read in Mister Ron's Basement (Number 431 -- Celebrated Jumping Frog, Numbers 195-199, Number 146 -- Million Pound Banknote, Nos. 67-71, and Number 6 -- The War Prayer) Podcast

Studying

- The Mark Twain Papers and Project of the Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley. Home to the largest archive of Mark Twain's papers and the editors of a critical edition of all of Mark Twain's writings.

- Mark Twain Room (Houses original manuscript of Huckleberry Finn)

- The University of California Press Publishers of the critical edition of Mark Twain's writings.

- Elmira College Center for Mark Twain Studies

- Ever the Twain Shall Meet, a guide to Mark Twain on the Web

- "The Mark Twain they didn’t teach us about in school", by Helen Scott, from International Socialist Review 10, Winter 2000, pp.61-65.

Life

- Full text of the biography Mark Twain by Archibald Henderson

- The Mark Twain House in Hartford, CT

- The Mark Twain Boyhood Home in Hannibal, MO

- The Hannibal Courier Post A Look at the Life and Works of Mark Twain

- Mark Twain: Known To Everyone—Liked By All, a Ken Burns film shown on PBS.

- Literary Pilgrimages—Mark Twain sites

- Cat Angels Jeff Rovin Harper Paperbacks ISBN 0-06-100972-5

Sellers of Mark Twain First Edition books

Other

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories:- Mark Twain

- American humorists

- American novelists

- American satirists

- American short story writers

- American travel writers

- Alternate history writers

- American memoirists

- Missouri writers

- Philippine-American War people

- People who declared bankruptcy

- American autodidacts

- American humanists

- American Presbyterians

- People from Missouri

- Scottish-Americans

- American vegetarians

- Quincy-Hannibal Area

- People from St. Louis

- People known by pseudonyms

- 1835 births

- 1910 deaths

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- Ailurophiles