| Revision as of 21:51, 4 December 2006 edit162.126.215.129 (talk) ←Blanked the page← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:52, 4 December 2006 edit undoSkyBoxx (talk | contribs)187 edits rv vandalismNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{redirect|The Colossus of Rhodes|the film by Sergio Leone|Il Colosso di Rodi}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The '''Colossus of Rhodes''' was a giant ] of the ] ] ], erected on the ] ] of ] by ], a pupil of ], between ] and ]. It was roughly the same size as the ] in ], although it stood on a lower ]. It is one of the ]. | |||

| ==The decision to erect the statue== | |||

| {{Main|Siege of Rhodes}} | |||

| ] died at an early age in ] without having had time to put into place any plans for his succession. Fighting broke out among his generals, the '']'', with three of them eventually dividing up much of his empire in the Mediterranean area. During the fighting Rhodes had sided with ], and when Ptolemy eventually took control of ], Rhodes and Ptolemaic Egypt formed an alliance which controlled much of the trade in the eastern Mediterranean. | |||

| Another of Alexander's generals, ], was upset by this turn of events. In 305 BC he had his son ] (now a famous general in his own right) invade Rhodes with an army of 40,000. However, the city was well defended, and Demetrius—whose name "Poliorcetes" signifies the "besieger of cities"—had to start construction of a number of massive ] in order to gain access to the walls. The first was mounted on six ships, but these were capsized in a storm before they could be used. He tried again with an even larger land-based tower named '']'', but the Rhodian defenders stopped this by flooding the land in front of the walls so that the rolling tower could not move. In 304 BC a relief force of ships sent by Ptolemy arrived, and Demetrius's army left in a hurry, leaving most of their siege equipment. Despite his failure at Rhodes, Demetrius earned the nickname ''Poliorcetes'' by his successes elsewhere. | |||

| To celebrate their victory, the Rhodians decided to build a giant statue of their patron god, ]. Construction was left to the direction of Chares, a native of Rhodes, who had been involved with large-scale statues before. His teacher, the famed sculptor Lysippus, had constructed a 18 ] high statue of ]. In order to pay for the construction of the Colossus, the Rhodians sold all of the siege equipment that Demetrius left behind in front of their city. | |||

| ], part of his series of the Seven Wonders of the World]] | |||

| ==Construction== | |||

| Ancient accounts (which differ to some degree) describe the structure as being built around several stone columns (or towers of blocks) forming the interior of the structure, which stood on a fifteen-meter-high (fifty-foot) white marble pedestal near the Mandraki harbour entrance. Other sources place the Colossus on a breakwater in the harbour. Iron beams were embedded in the stone towers, and bronze plates attached to the bars formed the visible skin of the sculpture. Much of the iron and bronze was reforged from the various weapons Demetrius's army left behind, and the abandoned second siege tower was used for scaffolding around the lower levels during construction. Upper portions were built with the use of a large earthen ramp. The statue itself was over 34 metres (110 feet) tall. | |||

| After twelve years, in 280 BC, the great statue was completed. | |||

| ==Destruction== | |||

| The statue stood for only fifty-six years until Rhodes was hit by an ] in 224 BC. The statue snapped at the knees and fell over onto the land. ] offered to pay for the reconstruction of the statue, but an ] made the Rhodians afraid that they had offended Helios, and they declined to rebuild it. The remains lay on the ground for over 800 years, and even broken, they were so impressive that many travelled to see them. ] remarked that few people could wrap their arms around the fallen thumb and that each of its fingers was larger than most statues. | |||

| In AD 654 an Arab force under ] captured Rhodes, and according to the chronicler ], the remains were sold to a travelling salesman from ]. The buyer had the statue broken down, and transported the bronze scrap on the backs of 900 camels to his home. Pieces continued to turn up for sale for years, after being found along the caravan route. | |||

| ==The myth== | |||

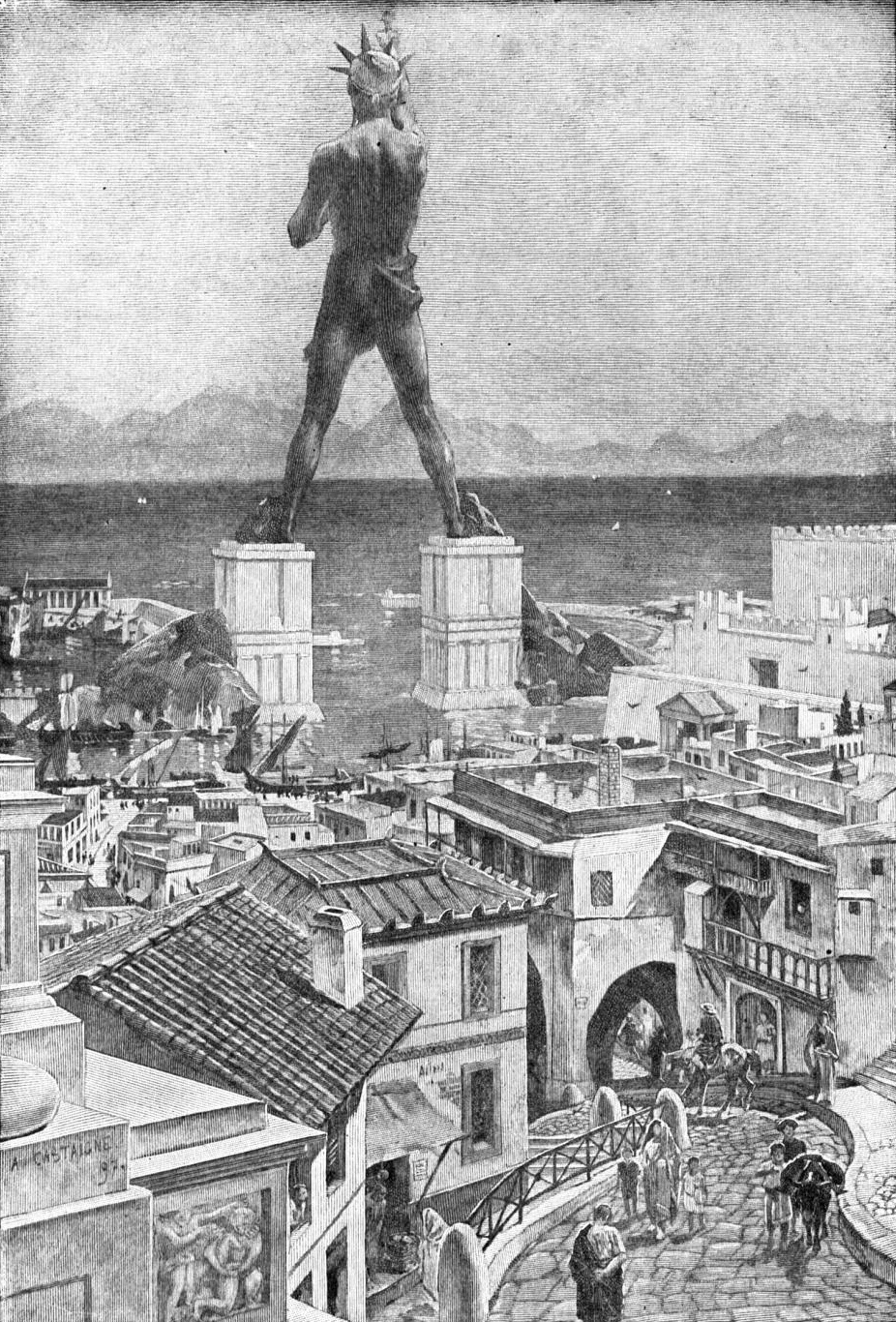

| The harbour-straddling Colossus was a figment of later imaginations. Many older illustrations (above) show the statue with one foot on either side of the harbour mouth with ships passing under it: "… the brazen giant of Greek fame, with conquering limbs astride from land to land …" ("]", the poem inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty). | |||

| Shakespeare's Cassius in '']'' (I,ii,136–38) says of Caesar: | |||

| :Why man, he doth bestride the narrow world | |||

| :Like a Colossus, and we petty men | |||

| :Walk under his huge legs and peep about | |||

| :To find ourselves dishonourable graves | |||

| ==The Colossus in modern times== | |||

| ] | |||

| *Media reports in 1989 initially suggested that large stones found on the seabed off the coast of Rhodes might have been the remains of the Colossus; however this theory was later shown to be without foundation. | |||

| *There has been much debate as to whether to rebuild the Colossus. Those in favour say it would boost tourism in Rhodes greatly, but those against construction say it would cost too large an amount (over 100 million ]). This idea has been revived many times since it was first proposed in 1970 but, due to lack of funding, work has not yet started. The plans for the Colossus have been in the works since 1998 by the Greek-Cypriot artist ]. | |||

| *In ]'s ] film ''Il Colosso di Rodi'' (1961) the Colossus stands spread-legged over the only entrance to Rhodes' harbor. In this instance the statue is hollow (like the ]) and is armed with defensive weaponry. | |||

| *]'s poem "The Colossus", refers to the Colossus of Rhodes. Perhaps the most famous reference to the Colossus, however, is in the immortal poem, "The New Colossus," by ], written in 1883 and inscribed on a plaque at the Statue of Liberty in New York City's harbor. | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| :Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,<br> | |||

| :With conquering limbs astride from land to land;<br> | |||

| :Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand<br> | |||

| :A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame<br> | |||

| :Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name<br> | |||

| :Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand<br> | |||

| :Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command<br> | |||

| :The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.<br> | |||

| :"Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she<br> | |||

| :With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,<br> | |||

| :Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,<br> | |||

| :The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.<br> | |||

| :Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,<br> | |||

| :I lift my lamp beside the golden door!" | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| ==References== | |||

| *{{cite book | author=James R. Ashley | title=Macedonian Empire | publisher=McFarland & Company | year=2004 | id=ISBN 0-7864-1918-0}} | |||

| == External links == | |||

| * | |||

| {{Seven wonders}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 21:52, 4 December 2006

"The Colossus of Rhodes" redirects here. For the film by Sergio Leone, see Il Colosso di Rodi.

The Colossus of Rhodes was a giant statue of the Greek god Helios, erected on the Greek island of Rhodes by Chares of Lindos, a pupil of Lysippos, between 292 and 280 BC. It was roughly the same size as the Statue of Liberty in New York, although it stood on a lower platform. It is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The decision to erect the statue

Main article: Siege of RhodesAlexander the Great died at an early age in 323 BC without having had time to put into place any plans for his succession. Fighting broke out among his generals, the Diadochi, with three of them eventually dividing up much of his empire in the Mediterranean area. During the fighting Rhodes had sided with Ptolemy, and when Ptolemy eventually took control of Egypt, Rhodes and Ptolemaic Egypt formed an alliance which controlled much of the trade in the eastern Mediterranean.

Another of Alexander's generals, Antigonus I Monophthalmus, was upset by this turn of events. In 305 BC he had his son Demetrius Poliorcetes (now a famous general in his own right) invade Rhodes with an army of 40,000. However, the city was well defended, and Demetrius—whose name "Poliorcetes" signifies the "besieger of cities"—had to start construction of a number of massive siege towers in order to gain access to the walls. The first was mounted on six ships, but these were capsized in a storm before they could be used. He tried again with an even larger land-based tower named Helepolis, but the Rhodian defenders stopped this by flooding the land in front of the walls so that the rolling tower could not move. In 304 BC a relief force of ships sent by Ptolemy arrived, and Demetrius's army left in a hurry, leaving most of their siege equipment. Despite his failure at Rhodes, Demetrius earned the nickname Poliorcetes by his successes elsewhere. To celebrate their victory, the Rhodians decided to build a giant statue of their patron god, Helios. Construction was left to the direction of Chares, a native of Rhodes, who had been involved with large-scale statues before. His teacher, the famed sculptor Lysippus, had constructed a 18 metre high statue of Zeus. In order to pay for the construction of the Colossus, the Rhodians sold all of the siege equipment that Demetrius left behind in front of their city.

Construction

Ancient accounts (which differ to some degree) describe the structure as being built around several stone columns (or towers of blocks) forming the interior of the structure, which stood on a fifteen-meter-high (fifty-foot) white marble pedestal near the Mandraki harbour entrance. Other sources place the Colossus on a breakwater in the harbour. Iron beams were embedded in the stone towers, and bronze plates attached to the bars formed the visible skin of the sculpture. Much of the iron and bronze was reforged from the various weapons Demetrius's army left behind, and the abandoned second siege tower was used for scaffolding around the lower levels during construction. Upper portions were built with the use of a large earthen ramp. The statue itself was over 34 metres (110 feet) tall.

After twelve years, in 280 BC, the great statue was completed.

Destruction

The statue stood for only fifty-six years until Rhodes was hit by an earthquake in 224 BC. The statue snapped at the knees and fell over onto the land. Ptolemy III offered to pay for the reconstruction of the statue, but an oracle made the Rhodians afraid that they had offended Helios, and they declined to rebuild it. The remains lay on the ground for over 800 years, and even broken, they were so impressive that many travelled to see them. Pliny the Elder remarked that few people could wrap their arms around the fallen thumb and that each of its fingers was larger than most statues. In AD 654 an Arab force under Muawiyah I captured Rhodes, and according to the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor, the remains were sold to a travelling salesman from Edessa. The buyer had the statue broken down, and transported the bronze scrap on the backs of 900 camels to his home. Pieces continued to turn up for sale for years, after being found along the caravan route.

The myth

The harbour-straddling Colossus was a figment of later imaginations. Many older illustrations (above) show the statue with one foot on either side of the harbour mouth with ships passing under it: "… the brazen giant of Greek fame, with conquering limbs astride from land to land …" ("The New Colossus", the poem inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty). Shakespeare's Cassius in Julius Caesar (I,ii,136–38) says of Caesar:

- Why man, he doth bestride the narrow world

- Like a Colossus, and we petty men

- Walk under his huge legs and peep about

- To find ourselves dishonourable graves

The Colossus in modern times

- Media reports in 1989 initially suggested that large stones found on the seabed off the coast of Rhodes might have been the remains of the Colossus; however this theory was later shown to be without foundation.

- There has been much debate as to whether to rebuild the Colossus. Those in favour say it would boost tourism in Rhodes greatly, but those against construction say it would cost too large an amount (over 100 million euro). This idea has been revived many times since it was first proposed in 1970 but, due to lack of funding, work has not yet started. The plans for the Colossus have been in the works since 1998 by the Greek-Cypriot artist Nikolaos Kotziamanis.

- In Sergio Leone's sword and sandal film Il Colosso di Rodi (1961) the Colossus stands spread-legged over the only entrance to Rhodes' harbor. In this instance the statue is hollow (like the Statue of Liberty) and is armed with defensive weaponry.

- Sylvia Plath's poem "The Colossus", refers to the Colossus of Rhodes. Perhaps the most famous reference to the Colossus, however, is in the immortal poem, "The New Colossus," by Emma Lazarus, written in 1883 and inscribed on a plaque at the Statue of Liberty in New York City's harbor.

- Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

- With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

- Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

- A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

- Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

- Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

- Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

- The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

- "Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she

- With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

- Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

- The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

- Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

- I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

References

- James R. Ashley (2004). Macedonian Empire. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1918-0. page 75