| Revision as of 03:04, 26 September 2020 editEvolution and evolvability (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users24,410 edits →Biography: + Family from v:WikiJournal_of_Humanities/Abū_al-Faraj_ʿAlī_b._al-Ḥusayn_al-Iṣfahānī,_the_Author_of_the_Kitāb_al-Aghānī under CC BY license (doi:10.15347/wjh/2020.001)Tag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:05, 26 September 2020 edit undoEvolution and evolvability (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users24,410 edits + Education and Career from v:WikiJournal_of_Humanities/Abū_al-Faraj_ʿAlī_b._al-Ḥusayn_al-Iṣfahānī,_the_Author_of_the_Kitāb_al-Aghānī under CC BY license (doi:10.15347/wjh/2020.001)Tag: Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

| In short, al-Iṣfahānī came from a family well-entrenched in the networks of the ʿAbbāsid elite, which included the officials and the ]. Despite the epithet, al-Iṣfahānī, it does not seem that the Iṣfahānī family has much to do with the city, Isfahan. Rather, the family was mainly based in Sāmarrāʾ, from the generation of Aḥmad b. al-Ḥaytham, and then Baghdad.{{sfn|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|ref=al-Aghānī|loc=vol. 23, p. 21}} In the seats of the caliphate, a few members of this family worked as scribes, while maintaining friendship or alliance with other scribes, viziers, and notables.{{sfn|Su|2018a|p=421–432}} Like many of the court elite, al-Iṣfahānī’s family maintained an amicable relationship with the offspring of ʿAlī and allied with families, such as the Thawāba family,{{Efn|Besides the Āl Thawāba, one may count among the pro-ʿAlid or Shīʿī families the Banū Furāt and Banū Nawbakht.{{sfn|Su|2018a|p=429–430}}}} sharing their veneration of ʿAlī and ʿAlids. However, it is hard to pinpoint such a reverential attitude towards ʿAlids in terms of sectarian alignment, given the scanty information about al-Iṣfahānī’s family and the fluidity of sectarian identities at the time. | In short, al-Iṣfahānī came from a family well-entrenched in the networks of the ʿAbbāsid elite, which included the officials and the ]. Despite the epithet, al-Iṣfahānī, it does not seem that the Iṣfahānī family has much to do with the city, Isfahan. Rather, the family was mainly based in Sāmarrāʾ, from the generation of Aḥmad b. al-Ḥaytham, and then Baghdad.{{sfn|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|ref=al-Aghānī|loc=vol. 23, p. 21}} In the seats of the caliphate, a few members of this family worked as scribes, while maintaining friendship or alliance with other scribes, viziers, and notables.{{sfn|Su|2018a|p=421–432}} Like many of the court elite, al-Iṣfahānī’s family maintained an amicable relationship with the offspring of ʿAlī and allied with families, such as the Thawāba family,{{Efn|Besides the Āl Thawāba, one may count among the pro-ʿAlid or Shīʿī families the Banū Furāt and Banū Nawbakht.{{sfn|Su|2018a|p=429–430}}}} sharing their veneration of ʿAlī and ʿAlids. However, it is hard to pinpoint such a reverential attitude towards ʿAlids in terms of sectarian alignment, given the scanty information about al-Iṣfahānī’s family and the fluidity of sectarian identities at the time. | ||

| === Education and career === | |||

| The Iṣfahānī family’s extensive social outreach is reflected in al-Iṣfahānī’s sources. Among the direct informants whom al-Iṣfahānī cites in his works, one finds the members of his own family, who were further connected to other notable families, as mentioned above,{{sfn|Su|2018a|p=421–432}}{{sfn|Khalafallāh|1962|p=41–51}} the Āl Thawāba,{{Efn|Al-Iṣfahānī’s sources are al-ʿAbbās b. Aḥmad b. Thawāba and Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad b. Thawāba, al-Iṣfahānī’s grandfather from the maternal side, who is cited indirectly.{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=29, 133}}|name=fn19}} the ],{{Efn|Al-Iṣfahānī has three informants from the Banū Munajjim, whose members were associated with the ʿAbbāsid court as boon companions, scholars, or astrologists: Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā b. ʿAlī (262–327/876–940); ʿAlī b. Hārūn b. ʿAlī (277–352/890–963); and Yaḥyā b. ʿAlī b. Yaḥyā (241–300/855–912).{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=38, 40, 68–69}} About the Banū Munajjim; see:{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2012|p=}}|name=fn20}} the ],{{Efn|The Yazīdīs were famed for its members’ mastery of poetry, the Qurʾānic readings, the ], and philology. Muḥammad b. al-ʿAbbās al-Yazīdī (d. ''c''. 228–310/842–922) was the tutor of the children of the caliph, al-Muqtadir (r. 295–320/908–932), and transmitted Abū ʿUbayda’s ''Naqāʾiḍ'', Thaʿlab’s ''Majālis'', and the works of his family; many of his narrations are preserved in the ''Aghānī''.{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=54–56}}{{sfn|Sellheim|2012|p=}}|name=fn21}} the ],{{Efn|The association with the Ṣūlīs likely began in the generation of al-Iṣfahānī’s grandfather, Muḥammad b. Aḥmad, who was close to Ibrāhīm b. al-ʿAbbās al-Ṣūlī; see above, the ]. Al-Iṣfahānī’s direct sources from this family are the famous al-Ṣūlī, Muḥammad b. Yaḥyā (d. 335/946 or 336/947), who was the boon companion of a number of the caliphs and a phenomenal chess player; his son, Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad al-Ṣūlī; and al-ʿAbbās b. ʿAlī, known as Ibn Burd al-Khiyār. See:{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=32, 64–65}}{{sfn|ref=al-Aghānī|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|loc=vol. 9, p. 229}} See also:{{sfn|ref=al-Fihrist|Ibn al-Nadīm, ''al-Fihrist''|p=167}}{{sfn|Leder|2012|p=}}|name=fn22}} the Banū Ḥamdūn,{{Efn|The Banū Ḥamdūn were known for their boon companionship at the ʿAbbāsid court in the ninth century; al-Iṣfahānī’s informant is ʿAbdallāh b. Aḥmad b. Ḥamdūn;{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=30}} about the Banū Ḥamdūn; see:{{sfn|ref=al-Fihrist|Ibn al-Nadīm, ''al-Fihrist''|p=161}}{{sfn|Vadet|2012|p=}}|name=fn23}} the Ṭāhirids,{{Efn|Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad b. ʿAbdallāh b. Ṭāhir, identified by al-Iṣfahānī as the nephew of ʿUbaydallāh b. ʿAbdallāh b. Ṭāhir (d. 300/913), is the son of Muḥammad b. ʿAbdallāh b. Ṭāhir (d. 296/908–9), the governor of Khurāsān.{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=69}}{{sfn|ref=al-Aghānī|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|loc=vol. 21, p. 48}} See also:{{sfn|Zetterstéen|2012|p=}}{{sfn|Bosworth|Marín|Smith|2012|p=}}|name=fn24}} the Banū al-Marzubān,{{Efn|Al-Iṣfahānī mentions a conversation between his father and Muḥammad b. Khalaf b. al-Marzubānī and notes the long-term friendship and marital tie between the two families; see:{{sfn|ref=al-Aghānī|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|loc=vol. 24, p. 37}} I owe this reference to: {{sfn|Kilpatrick|2003|p=17}} Muḥammad b. Khalaf b. al-Marzubān is a ubiquitous informant in the ''Aghānī''; see:{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=58–59}}|name=fn25}} and the Ṭālibids.{{Efn|The Ṭālibid informants of al-Iṣfahānī comprise: ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAlī b. Ḥamza; ʿAlī b. Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad; ʿAlī b. Muḥammad b. Jaʿfar; Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad b. Jaʿfar; Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. Ḥamza; see: {{sfn|Günther|1991|p=140–141; 141–144; 150; 161–162; 190–191}}|name=fn26}} | |||

| Given that al-Iṣfahānī and his family very likely settled in Baghdad around the beginning of the tenth century,{{Efn|al-Iṣfahānī’s uncle, al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad, mentioned in the ''Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām'', either settled in Baghdad with him or at least active for some time there; see:{{sfn|ref=al-Aghānī|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|loc=vol. 23, p. 21}}{{sfn|ref=Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām|al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, ''Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām''|loc=vol. 8, p. 440}}}} it is no surprise that he transmitted from a considerable number of the inhabitants of or visitors to that city, such as, to name just a few: Jaḥẓa (d. 324/936),{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=34–35}} al-Khaffāf,{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=46–47}} ʿAlī b. Sulaymān al-Akhfash (d. 315/927 or 316/928),{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=41–42}} and Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/922).{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=58}} Like other scholars of his time, al-Iṣfahānī travelled in pursuit of knowledge. Although the details are not sufficient for us to establish the dates of his journeys, based on the chains of transmission (''asānīd'', sing. ''isnād'') al-Iṣfahānī cites consistently and meticulously in every report, it is certain that he transmitted from ʿAbd al-Malik b. Maslama and ʿĀṣim b. Muḥammad in Antakya;{{sfn|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|ref=al-Aghānī|loc=vol. 13, p. 25; vol. 14, p. 46–50}} ʿAbdallāh b. Muḥammad b. Isḥāq in ];{{sfn|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|ref=al-Aghānī|loc=vol. 17, p. 157}} and Yaḥyā b. Aḥmad b. al-Jawn in ].{{sfn|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|ref=al-Aghānī|loc=vol. 24, p. 67}} If we accept the ascription of the ''Kitāb Adab al-ghurabāʾ'' to al-Iṣfahānī, then he once visited ] besides other towns such as Ḥiṣn Mahdī, Mattūth, and Bājistrā.{{sfn|Azarnoosh|1992|p=721}}{{sfn|Kilpatrick|2003|p=18}} Yet, none of these cities seems to have left as tremendous an impact upon al-Iṣfahānī as ] and Baghdad did. While al-Iṣfahānī’s Baghdādī informants were wide-ranging in their expertise as well as sectarian and theological tendencies, his Kūfan sources, to a certain degree, can be characterised as either Shīʿī or keen on preserving and disseminating memory that favours ʿAlī and his family. For example, Ibn ʿUqda (d. 333/944), mentioned in both the ''Aghānī'' and the ''Maqātil,'' is invariably cited for the reports about the ] and their merits.{{sfn|Günther|1991|p=127–131}}{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=36–37}}{{sfn|Su|2016|p=204–209}}{{efn|About Ibn ʿUqd, see also:{{sfn|Brown|2008|p=55–58}}}} | |||

| The journey in search for knowledge taken by al-Iṣfahānī may not be particularly outstanding by the standard of his time,{{Efn|Compare, for instance, his teacher, al-Ṭabarī.{{sfn|Bosworth|2012|p=}}}} but the diversity of his sources’ occupations and fortes is beyond doubt impressive. His informants can be assigned into one or more of the following categories:{{Efn|It has to be kept in mind that the categorisation is based on the attributives given by al-Iṣfahānī. Just as al-Iṣfahānī was not a local Iṣfahānī, the subjects discussed here do not necessarily engage with the professions their ''nisbas'' indicate.}} philologists and grammarians;{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=41–42 (al-Akhfash); 60–61 (Ibn Durayd); 32 (Ibn Rustam); 30 (ʿAbd al-Malik al-Ḍarīr)}} singers and musicians;{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=42 (Dhukāʾ Wajh al-Ruzza); 34 (Jaḥẓa)}} booksellers and copyists (''ṣaḥḥāfūn'' or ''warrāqūn'', sing. ''ṣaḥḥāf'' or ]);{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=52–53 (ʿĪsā b. al-Ḥusayn al-Warrāq); 40 (ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn al-Warrāq); 37 (Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Ṣaḥḥāf); 31 (ʿAbd al-Wahhāb b. ʿUbayd al-Ṣaḥḥāf); 65 (Muḥammad b. Zakariyyā al-Ṣaḥḥāf)}} boon companions;{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=32 (Abū al-Qāsim al-Shīrbābakī)}}{{Efn|See also the footnotes above: {{Efn|name=fn20}}{{Efn|name=fn22}}{{Efn|name=fn23}}}} tutors (''muʾaddibūn'', sing. ''muʾaddib'');{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=32 (Aḥmad b. al-ʿAbbās al-Muʾaddib); 35 (Aḥmad b. ʿImrān al-Muʾaddib); 61–62 (Muḥammad b. al-Ḥusayn al-Muʾaddib); 62 (Muḥammad b. ʿImrān al-Muʾaddib)}} scribes (''kuttāb'', sing. ]);{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=43–44 (Jaʿfar b. Qudāma al-Kātib); 50–51 (al-Ḥusayn b. al-Qāsim al-Kawkabī al-Kātib); 53 (Isḥāq b. al-Ḍaḥḥāk al-Kātib); 41 (ʿAlī b. Ṣāliḥ al-Kātib); 39 (ʿAlī b. al-ʿAbbās al-Ṭalḥī al-Kātib); 39–40 (ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Kātib); 49 (al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad al-Kātib); 57 (Muḥammad b. Baḥr al-Iṣfahānī al-Kātib)}} imams or preachers (''khuṭabāʾ'', sing. ]); {{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=61 (Muḥammad b. Ḥusayn al-Kindī was al-Iṣfahānī’s tutor and the preacher at the congregational mosque in Qādisiyya); 40–41 (ʿAlī b. Muḥammad, an imam of a Kūfan mosque)}}{{sfn|al-Iṣfahānī, ''Kitāb al-Aghānī''|ref=al-Aghānī|loc=vol. 15, p. 255; vol. 19, p. 38; vol. 20, p. 163; vol. 21, p. 158}} religious scholars (of the ''ḥadīth'', the Qurʾānic recitations and exegeses, or jurisprudence) and judges;{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=30 (ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Dāwūd al-Sijistānī); 36–37 (Ibn ʿUqda); 58 (Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī); 59–60 (Muḥammad b. Khalaf Wakīʿ)}} poets;{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=42 (ʿĀṣim b. Muḥammad al-Shāʿir); 49 (al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad al-Shāʿir)}} and '']'' (transmitters of reports of all sorts, including genealogical, historical, and anecdotal reports).{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=37 (Aḥmad b. Sulaymān al-Ṭūsī); 37–38 (Ibn ʿAmmār); 42–43 (Abū Khalīfa al-Jumaḥī); 45–46 (al-Ḥaramī b. Abī al-ʿAlāʾ)}} The variety of the narrators and their narrations enriched al-Iṣfahānī’s literary output, which covers a wide range of topics from amusing tales to the accounts of the ʿAlids’ martyrdom.{{Efn|See ], below}} His erudition is best illustrated by Abū ʿAlī al-Muḥassin al-Tanūkhī’s (329–384/941–994) comment: | |||

| With his encyclopaedic knowledge of music, musicians, poetry, poets, genealogy, history, and other subjects, al-Iṣfahānī established himself as a learned scholar and teacher.{{sfn|al-Hamawī, ''Muʿjam al-udabāʾ''|ref=Muʿjam al-udabāʾ|loc=vol. 13, p. 129–130}}{{sfn|Khalafallāh|1962|p=168–169}}{{sfn|al-Aṣmaʿī|1951|p=73–85}}{{sfn|ʿĀṣī|1993|p=24–30}} | |||

| He was also a scribe and this is not surprising, given his families’ scribal connections, but the details of his ''kātib'' activities are rather opaque.{{Efn|For the few references by al-Iṣfahānī to his administrative tasks, see:{{sfn|Kilpatrick|2003|p=18}}}} Although both al-Tanūkhī and al-Baghdādī refer to al-Iṣfahānī with the attribute, ''kātib'', they mention nothing of where he worked or for whom.{{sfn|al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, ''Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām''|ref=Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām|loc=vol. 13, p. 337}}{{sfn|al-Tanūkhī, ''al-Faraj''|ref=al-Faraj|loc=vol. 2, p. 334}}{{sfn|al-Tanūkhī, ''Nishwār''|ref=Nishwār|loc=vol. 1, p. 18}} The details of his job as a scribe only come later, with Yāqūt, many of whose reports about al-Iṣfahānī prove problematic. For instance, a report from Yāqūt claims that al-Iṣfahānī was the scribe of Rukn al-Dawla (d. 366/976) and mentions his resentment at Abū al-Faḍl b. al-ʿAmīd (d. 360/970).{{sfn|al-Hamawī, ''Muʿjam al-udabāʾ''|ref=Muʿjam al-udabāʾ|loc=vol. 13, p. 110–111}} However, the very same report is mentioned by Abū Ḥayyān al-Tawḥīdī (active fourth/tenth century{{sfn|Stern|2012|p=}}) in his ''Akhlāq al-wazīrayn'', where the aforementioned scribe of Rukn al-Dawla is identified as Abū al-Faraj Ḥamd b. Muḥammad, not Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī.{{sfn|Azarnoosh|1992|p=726–727}}{{sfn|al-Tawḥīdī, ''Akhlāq al‑wazīrayn''|ref=Akhlāq al‑wazīrayn|p=421–422}}{{Quote|Amongst the Shīʿī narrators whom we have seen, none has memorised poems, melodies, reports, traditions (''al-āthār''), ''al-aḥādīth al-musnada'' (narrations with chains of transmission, including the Prophetic ''ḥadīth''), and genealogy by heart like Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī. Very proficient in these matters, he is also knowledgeable in the military campaigns and the biography of the Prophet (''al-maghāzī'' and ''al-sīra''), lexicography, grammar, legendary tales (''al-khurāfāt''), and the accomplishments required of courtiers (''ālat al-munādama''), like falconry (''al-jawāriḥ''), veterinary science (''al-bayṭara''), some notions of medicine (''nutafan min al-ṭibb''), astrology, drinks (''al-ashriba''), and other things.|author=Al-Khaṭīb{{sfn|ref=Wafayāt|Ibn Khallikān, ''Wafayāt''|loc=vol. 3, p. 307}}{{sfn|ref=Siyar|al-Dhahabī, ''Siyar''|p=2774}}{{sfn|ref=Inbāh|al-Qifṭī, ''Inbāh''|loc=vol. 2, p. 251}}{{efn|It is noteworthy that the first sentence of this quote is written differently from the works given here in al-Khaṭīb’s ''Tārīkh''.{{sfn|ref=Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām|al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, ''Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām''|loc=vol. 13, p. 339}}}}}}Thus, it is hard to know with certainty how and where al-Iṣfahānī was engaged in his capacity as a ''kātib''. Nevertheless, al-Iṣfahānī’s association with the vizier, ] (291–352/903–963), is well-documented. The friendship between the two began before al-Muhallabī’s vizierate in 339/950.{{sfn|al-Hamawī, ''Muʿjam al-udabāʾ''|ref=Muʿjam al-udabāʾ|loc=vol. 13, p. 105}}{{Efn|Among the frequently cited sources in the ''Aghānī'' is Ḥabīb b. Naṣr al-Muhallabī (d. 307/919), presumably from the Muhallabid family, but it is not clear how this informant relates to Abū Muḥammad al-Muhallabī; see:{{sfn|Fleischhammer|2004|p=44}}}} The firm relationship between them is supported by al-Iṣfahānī’s poetry collected by al-Thaʿālibī (350–429/961–1038): half of the fourteen poems are panegyrics dedicated to al-Muhallabī.{{sfn|al-Thaʿālibī, ''Yatīmat''|ref=Yatīmat|loc=vol. 3, p. 127–131}} In addition, al-Iṣfahānī’s own work, ''al-Imāʾ al-shawāʿir'' (“Enslaved Women Who Composed Poetry”), refers to the vizier — presumably, al-Muhallabī — as his dedicatee.{{sfn|al-Iṣfahānī, ''al-Imāʿ al-shawāʿir''|ref=al-shawāʿir|p=23}} His no longer surviving ''Manājīb al-khiṣyān'' (“The Noble Eunuchs”), which addresses two castrated male singers owned by al-Muhallabī, was composed for him.{{sfn|al-Hamawī, ''Muʿjam al-udabāʾ''|ref=Muʿjam al-udabāʾ|loc=vol. 13, p. 100}} His ''magnum opus'', the ''Aghānī'', was very likely intended for him, as well.{{Efn|See discussion below, the ]}} As a return for his literary efforts, according to al-Tanūkhī, al-Iṣfahānī frequently received rewards from the vizier.{{sfn|al-Tanūkhī, ''Nishwār''|ref=Nishwār|loc=vol. 1, p. 74}} Furthermore, for the sake of their long-term friendship and out of his respect for al-Iṣfahānī’s genius, al-Muhallabī exceptionally tolerated al-Iṣfahānī’s uncouth manners and poor personal hygiene.{{sfn|al-Hamawī, ''Muʿjam al-udabāʾ''|ref=Muʿjam al-udabāʾ|loc=vol. 13, p. 101–103}} The sources say nothing about al-Iṣfahānī’s fate, after al-Muhallabī’s death. In his last years, according to his student, Muḥammad b. Abī al-Fawāris, he suffered from senility (''khallaṭa'').{{sfn|al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, ''Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām''|ref=Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām|loc=vol. 13, p. 340}}{{efn|See also: {{sfn|Kilpatrick|2003|p=19}}}} | |||

| ==''Book of Songs'' & Other Works== | ==''Book of Songs'' & Other Works== | ||

Revision as of 03:05, 26 September 2020

Arab historian For other people named Al-Isfahani, see Al-Isfahani (disambiguation). For other people named Abu al-Faraj, see Abu al-Faraj (disambiguation).| Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani | |

|---|---|

| أبو الفرج الأصفهاني | |

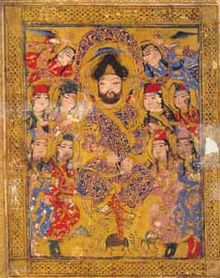

Illustration from Kitab al-aghani (Book of Songs), 1216-20, by Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, a collection of songs by famous musicians and Arab poets. Illustration from Kitab al-aghani (Book of Songs), 1216-20, by Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, a collection of songs by famous musicians and Arab poets. | |

| Born | 897 (897) Isfahan |

| Died | 967 (aged 69–70) Baghdad |

| Known for | Book of Songs |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | History |

| Patrons | Sayf ad-Dawlah |

Ali ibn al-Husayn al-Iṣfahānī (Template:Lang-ar), also known as Abul-Faraj, (full form: Abū al-Faraj ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn b. Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. al-Ḥaytham al-Umawī al-Iṣfahānī) (284/897–356AH/967CE) was a litterateur, genealogist, poet, musicologist, scribe, and boon companion in the tenth century. He was of Arab-Quraysh origin and mainly based in Baghdad. He is best known as the author of Kitāb al-Aghānī (“The Book of Songs”), which includes information about the earliest attested periods of Arabic music (from the seventh to the ninth centuries) and the lives of poets and musicians from the pre-Islamic period to al-Iṣfahānī’s time. Given his contribution to the documentation of the history of Arabic music, al-Iṣfahānī is characterised by Sawa as “a true prophet of modern ethnomusicology”.

Dates

The commonly accepted dates of al-Iṣfahānī’s birth and death are 284AH/897–8CE and 356/967. However, the credibility of these dates is to be treated with discretion. The dates are given by al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī (392–463/1002–1071), who bases his information on the testimony of al-Iṣfahānī’s student, Muḥammad b. Abī al-Fawāris (338–412/950–1022). The death date given by al-Khaṭīb is irreconcilable with a reference in the Kitāb Adab al-ghurabāʾ (“The Book of the Etiquettes of Strangers”), attributed to al-Iṣfahānī, to his being in the prime of youth (fī ayyām al-shabība wa-l-ṣibā) in 356/967. If we accept al-Iṣfahānī’s authorship of the Adab al-ghurabāʾ and the authenticity of all the accounts in it, none of the above dates makes sense. However, it is possible to calculate the approximate dates of his birth and death through the lifespans of his students and his direct informants. Muḥammad b. Abī al-Fawāris — the youngest to have transmitted from him — was born in 338/950. If we assume that Muḥammad started to attend al-Iṣfahānī’s lectures at the age of ten, then we may suggest that al-Iṣfahānī was still active in 348/960 onwards or a little later. Among his direct informants, the one who died earliest is Yaḥyā b. ʿAlī b. Yaḥyā al-Munajjim, who lived from 241/855 to 300/912. Again, if we postulate that al-Iṣfahānī transmitted from Yaḥyā when he was at least ten years old, we can infer that he was born before 290/902. Therefore, al-Iṣfahānī’s intellectual activity took place in the first six decades of the tenth century, from about 290/902 to 348/960. No source places his death earlier than 356/967.

Biography

Abu al-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī was born in Isfahan, Persia (present-day Iran) but spent his youth and made his early studies in Baghdad (present-day Iraq). He was a direct descendant of the last of the Umayyad caliphs, Marwan II, and was thus connected with the Umayyad rulers in al-Andalus, and seems to have kept up a correspondence with them and to have sent them some of his works. He became famous for his knowledge of early Arabian antiquities.

His later life was spent in various parts of the Islamic world, in Aleppo with its Hamdanid governor Sayf ad-Dawlah (to whom he dedicated the Book of Songs), in Ray with the Buwayhid vizier Ibn 'Abbad, and elsewhere.

Family

The epithet, al-Iṣfahānī, refers to the city, Isfahan, on the Iranian plateau. Instead of indicating al-Iṣfahānī’s birthplace, this epithet seems to be common to al-Iṣfahānī’s family. Every reference al-Iṣfahānī makes to his paternal relatives includes the attributive, al-Iṣfahānī. According to Ibn Ḥazm (384–456/994–1064), some descendants of the last Umayyad caliph, Marwān b. Muḥammad (72–132/691–750), al-Iṣfahānī’s forefather, settled in Isfahan. However, it has to be borne in mind that the earliest information we have regarding al-Iṣfahānī’s family history only dates to the generation of his great-grandfather, Aḥmad b. al-Ḥaytham, who settled in Sāmarrāʾ sometime between 221/835–6 and 232/847.

Based on al-Iṣfahānī’s references in the Kitāb al-Aghānī (hereafter, the Aghānī), Aḥmad b. al-Ḥaytham seems to have led a privileged life in Sāmarrāʾ, while his sons were well-connected with the elite of the ʿAbbāsid capital at that time. His son, ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz b. Aḥmad, was “one of the high ranking scribes in the days of al-Mutawakkil (r. 232–247/847–861) (min kibār al-kuttāb fī ayyām al-Mutawakkil)”. Another son, Muḥammad b. Aḥmad (viz. al-Iṣfahānī’s grandfather), was associated with the ʿAbbāsid officials, the vizier Ibn al-Zayyāt (d. 233/847), the scribe Ibrāhīm b. al-ʿAbbās al-Ṣūlī (176–243/792–857), and the vizier ʿUbaydallāh b. Sulaymān (d. 288/901), besides the Ṭālibid notables, above all, al-Ḥusayn b. al-Ḥusayn b. Zayd, who was the leader of the Banū Hāshim of his time. The close ties with the ʿAbbāsid court continued in the generation of Muḥammad’s sons, al-Ḥasan and al-Ḥusayn (al-Iṣfahānī’s father).

In various places in the Aghānī, al-Iṣfahānī refers to Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad b. Thawāba (from the Āl Thawāba) as his grandfather on his mother’s side. It is often suggested that the family of Thawāba, being Shīʿī, bequeathed their sectarian inclination to al-Iṣfahānī. However, the identification of the Thawāba family as Shīʿīs is only found in a late source, Yāqūt’s (574–626/1178–1225) work. Although it is not implausible for the family of Thawāba to have been Shīʿī-inclined in one way or another, since many elite families working under the ʿAbbāsid caliphate during this period of time indeed allied with ʿAlids or their partisans, there is no evidence that members of the Thawāba family embraced an extreme form of Shīʿism.

In short, al-Iṣfahānī came from a family well-entrenched in the networks of the ʿAbbāsid elite, which included the officials and the ʿAlids. Despite the epithet, al-Iṣfahānī, it does not seem that the Iṣfahānī family has much to do with the city, Isfahan. Rather, the family was mainly based in Sāmarrāʾ, from the generation of Aḥmad b. al-Ḥaytham, and then Baghdad. In the seats of the caliphate, a few members of this family worked as scribes, while maintaining friendship or alliance with other scribes, viziers, and notables. Like many of the court elite, al-Iṣfahānī’s family maintained an amicable relationship with the offspring of ʿAlī and allied with families, such as the Thawāba family, sharing their veneration of ʿAlī and ʿAlids. However, it is hard to pinpoint such a reverential attitude towards ʿAlids in terms of sectarian alignment, given the scanty information about al-Iṣfahānī’s family and the fluidity of sectarian identities at the time.

Education and career

The Iṣfahānī family’s extensive social outreach is reflected in al-Iṣfahānī’s sources. Among the direct informants whom al-Iṣfahānī cites in his works, one finds the members of his own family, who were further connected to other notable families, as mentioned above, the Āl Thawāba, the Banū Munajjim, the Yazīdīs, the Ṣūlīs, the Banū Ḥamdūn, the Ṭāhirids, the Banū al-Marzubān, and the Ṭālibids.

Given that al-Iṣfahānī and his family very likely settled in Baghdad around the beginning of the tenth century, it is no surprise that he transmitted from a considerable number of the inhabitants of or visitors to that city, such as, to name just a few: Jaḥẓa (d. 324/936), al-Khaffāf, ʿAlī b. Sulaymān al-Akhfash (d. 315/927 or 316/928), and Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/922). Like other scholars of his time, al-Iṣfahānī travelled in pursuit of knowledge. Although the details are not sufficient for us to establish the dates of his journeys, based on the chains of transmission (asānīd, sing. isnād) al-Iṣfahānī cites consistently and meticulously in every report, it is certain that he transmitted from ʿAbd al-Malik b. Maslama and ʿĀṣim b. Muḥammad in Antakya; ʿAbdallāh b. Muḥammad b. Isḥāq in Ahwāz; and Yaḥyā b. Aḥmad b. al-Jawn in Raqqa. If we accept the ascription of the Kitāb Adab al-ghurabāʾ to al-Iṣfahānī, then he once visited Baṣra besides other towns such as Ḥiṣn Mahdī, Mattūth, and Bājistrā. Yet, none of these cities seems to have left as tremendous an impact upon al-Iṣfahānī as Kūfa and Baghdad did. While al-Iṣfahānī’s Baghdādī informants were wide-ranging in their expertise as well as sectarian and theological tendencies, his Kūfan sources, to a certain degree, can be characterised as either Shīʿī or keen on preserving and disseminating memory that favours ʿAlī and his family. For example, Ibn ʿUqda (d. 333/944), mentioned in both the Aghānī and the Maqātil, is invariably cited for the reports about the ʿAlids and their merits.

The journey in search for knowledge taken by al-Iṣfahānī may not be particularly outstanding by the standard of his time, but the diversity of his sources’ occupations and fortes is beyond doubt impressive. His informants can be assigned into one or more of the following categories: philologists and grammarians; singers and musicians; booksellers and copyists (ṣaḥḥāfūn or warrāqūn, sing. ṣaḥḥāf or warrāq); boon companions; tutors (muʾaddibūn, sing. muʾaddib); scribes (kuttāb, sing. kātib); imams or preachers (khuṭabāʾ, sing. khaṭīb); religious scholars (of the ḥadīth, the Qurʾānic recitations and exegeses, or jurisprudence) and judges; poets; and akhbārīs (transmitters of reports of all sorts, including genealogical, historical, and anecdotal reports). The variety of the narrators and their narrations enriched al-Iṣfahānī’s literary output, which covers a wide range of topics from amusing tales to the accounts of the ʿAlids’ martyrdom. His erudition is best illustrated by Abū ʿAlī al-Muḥassin al-Tanūkhī’s (329–384/941–994) comment:

With his encyclopaedic knowledge of music, musicians, poetry, poets, genealogy, history, and other subjects, al-Iṣfahānī established himself as a learned scholar and teacher.

He was also a scribe and this is not surprising, given his families’ scribal connections, but the details of his kātib activities are rather opaque. Although both al-Tanūkhī and al-Baghdādī refer to al-Iṣfahānī with the attribute, kātib, they mention nothing of where he worked or for whom. The details of his job as a scribe only come later, with Yāqūt, many of whose reports about al-Iṣfahānī prove problematic. For instance, a report from Yāqūt claims that al-Iṣfahānī was the scribe of Rukn al-Dawla (d. 366/976) and mentions his resentment at Abū al-Faḍl b. al-ʿAmīd (d. 360/970). However, the very same report is mentioned by Abū Ḥayyān al-Tawḥīdī (active fourth/tenth century) in his Akhlāq al-wazīrayn, where the aforementioned scribe of Rukn al-Dawla is identified as Abū al-Faraj Ḥamd b. Muḥammad, not Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī.

Amongst the Shīʿī narrators whom we have seen, none has memorised poems, melodies, reports, traditions (al-āthār), al-aḥādīth al-musnada (narrations with chains of transmission, including the Prophetic ḥadīth), and genealogy by heart like Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī. Very proficient in these matters, he is also knowledgeable in the military campaigns and the biography of the Prophet (al-maghāzī and al-sīra), lexicography, grammar, legendary tales (al-khurāfāt), and the accomplishments required of courtiers (ālat al-munādama), like falconry (al-jawāriḥ), veterinary science (al-bayṭara), some notions of medicine (nutafan min al-ṭibb), astrology, drinks (al-ashriba), and other things.

— Al-Khaṭīb

Thus, it is hard to know with certainty how and where al-Iṣfahānī was engaged in his capacity as a kātib. Nevertheless, al-Iṣfahānī’s association with the vizier, Abū Muḥammad al-Muhallabī (291–352/903–963), is well-documented. The friendship between the two began before al-Muhallabī’s vizierate in 339/950. The firm relationship between them is supported by al-Iṣfahānī’s poetry collected by al-Thaʿālibī (350–429/961–1038): half of the fourteen poems are panegyrics dedicated to al-Muhallabī. In addition, al-Iṣfahānī’s own work, al-Imāʾ al-shawāʿir (“Enslaved Women Who Composed Poetry”), refers to the vizier — presumably, al-Muhallabī — as his dedicatee. His no longer surviving Manājīb al-khiṣyān (“The Noble Eunuchs”), which addresses two castrated male singers owned by al-Muhallabī, was composed for him. His magnum opus, the Aghānī, was very likely intended for him, as well. As a return for his literary efforts, according to al-Tanūkhī, al-Iṣfahānī frequently received rewards from the vizier. Furthermore, for the sake of their long-term friendship and out of his respect for al-Iṣfahānī’s genius, al-Muhallabī exceptionally tolerated al-Iṣfahānī’s uncouth manners and poor personal hygiene. The sources say nothing about al-Iṣfahānī’s fate, after al-Muhallabī’s death. In his last years, according to his student, Muḥammad b. Abī al-Fawāris, he suffered from senility (khallaṭa).

Book of Songs & Other Works

Al-Iṣfahānī is best known as the author of Kitāb al-Aghānī (“The Book of Songs”), an encyclopedia of over 20 volumes and editions. However, he additionally wrote poetry, an anthology of verses on the monasteries of Mesopotamia and Egypt, and a genealogical work.

- Kitāb al-Aġānī (كتاب الأغاني) 'Book of Songs', a collection of Arabic chants rich in information on Arab and Persian poets, singers and other musicians from the 7th - 10th centuries of major cities such as Mecca, Damascus, Isfahan, Rey, Baghdād and Baṣrah. The Book of Songs contains details of the ancient Arab tribes and courtly life of the Umayyads and provides a complete overview of the Arab civilization from the pre-Islamic Jahiliyya era, up to his own time. Abū ‘l-Faraj employs the classical Arabic genealogical devise, or isnad, (chain of transmission), to relate the biographical accounts of the authors and composers. Although originally the poems were put to music, the musical signs are no longer legible. Abū ‘l-Faraj spent in total 50 years creating this work, which remains an important historical source.

The first printed edition, published in 1868, contained 20 volumes. In 1888 Rudolf Ernst Brünnow published a 21st volume being a collection of biographies not contained in the Bulāq edition, edited from MSS in the Royal Library of Munich.

- Maqātil aṭ-Ṭālibīyīn (مقاتل الطالبيين}), Tālibid Fights, a collection of more than 200 biographies of the descendants of Abū Tālib ibn'Abd al-Muttalib, from the time of the Prophet Muḥammad to the writing of the book in 313 the Hijri (= 925/926 CE) who died in an unnatural way. As Abūl-Faraj said in the foreword to his work, he included only those Tālibids who rebelled against the government and were killed, slaughtered, executed or poisoned, lived underground, fled or died in captivity. The work is a major source for the Umayyad and Abbāsid Alid uprisings and the main source for the Hashimite meeting that took place after the assassination of the Umayyad Caliph al-Walīd II in the village of al-Abwā' between Mecca and Medina. At this meeting, al-'Abdallah made the Hashimites pledge an oath of allegiance to his son Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya as the new Mahdi.

- Kitāb al-Imā'āš-šawā'ir (كتاب الإماء الشواعر) 'The Book of the Poet-slaves', a collection of accounts of poetic slaves of the Abbasid period.

See also

Notes

- Other dates of death are in the 360s/970s and 357/967–68, suggested respectively by Ibn al-Nadīm (d. 385/995 or 388/998) and Abū Nuʿaym al-Iṣfahānī (336–430/948–1038)

- The attribution of Adab al-ghurabāʾ to al-Iṣfahānī is much disputed in current scholarship. The scholars who affirm al-Iṣfahānī as the author of Adab al-ghurabāʾ include: On the opposite side are:

- Al-Isfahani traces his descent to Marwan II as follows: Abu al-Faraj Ali ibn al-Husayn ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn al-Haytham ibn Abd al-Rahman ibn Marwan ibn Abd Allah ibn Marwan II ibn Muhammad ibn Marwan I.

- Another spelling, al-Iṣbahānī, is also used in secondary literature. Although al-Iṣbahānī is found in the oldest biographical sources and manuscripts, al-Iṣfahānī will be used in this article.

- This misconception, according to Azarnoosh, was first disseminated by Ṭāshkubrīzādah (d. 968/1560) and was thereafter followed by modern scholars.

- While most of the sources agree that al-Iṣfahānī was amongst the offspring of the last Umayyad caliph, Marwān b. Muḥammad, Ibn al-Nadīm alone claimed that he was a descendant of Hishām b. ʿAbd al-Malik (72–125/691–743). The majority opinion:

- A report in the Aghānī mentions Aḥmad b. al-Ḥaytham’s possession of slaves, which may indicate his being wealthy.

- For the identity of Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad b. Thawāba and other members of the Āl Thawāba,see:

- The term, Shīʿī, is used in its broadest sense in this article and comprises various still evolving groups, including Imāmī Shīʿīs, Zaydīs, Ghulāt, and mild or soft Shīʿīs (as per van Ess and Crone), as well as those who straddle several sectarian alignments. Such inclusiveness is necessitated by the lack of clear-cut sectarian delineation (as in the case of the Āl Thawāba, discussed here) in the early period.

- Both Kilpatrick and Azarnoosh follow Khalafallāh’s argument as to the Āl Thawāba’s impact upon al-Iṣfahānī’s Shīʿī conviction.

- Besides the Āl Thawāba, one may count among the pro-ʿAlid or Shīʿī families the Banū Furāt and Banū Nawbakht.

- Al-Iṣfahānī’s sources are al-ʿAbbās b. Aḥmad b. Thawāba and Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad b. Thawāba, al-Iṣfahānī’s grandfather from the maternal side, who is cited indirectly.

- ^ Al-Iṣfahānī has three informants from the Banū Munajjim, whose members were associated with the ʿAbbāsid court as boon companions, scholars, or astrologists: Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā b. ʿAlī (262–327/876–940); ʿAlī b. Hārūn b. ʿAlī (277–352/890–963); and Yaḥyā b. ʿAlī b. Yaḥyā (241–300/855–912). About the Banū Munajjim; see:

- The Yazīdīs were famed for its members’ mastery of poetry, the Qurʾānic readings, the ḥadīth, and philology. Muḥammad b. al-ʿAbbās al-Yazīdī (d. c. 228–310/842–922) was the tutor of the children of the caliph, al-Muqtadir (r. 295–320/908–932), and transmitted Abū ʿUbayda’s Naqāʾiḍ, Thaʿlab’s Majālis, and the works of his family; many of his narrations are preserved in the Aghānī.

- ^ The association with the Ṣūlīs likely began in the generation of al-Iṣfahānī’s grandfather, Muḥammad b. Aḥmad, who was close to Ibrāhīm b. al-ʿAbbās al-Ṣūlī; see above, the section on Family. Al-Iṣfahānī’s direct sources from this family are the famous al-Ṣūlī, Muḥammad b. Yaḥyā (d. 335/946 or 336/947), who was the boon companion of a number of the caliphs and a phenomenal chess player; his son, Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad al-Ṣūlī; and al-ʿAbbās b. ʿAlī, known as Ibn Burd al-Khiyār. See: See also:

- ^ The Banū Ḥamdūn were known for their boon companionship at the ʿAbbāsid court in the ninth century; al-Iṣfahānī’s informant is ʿAbdallāh b. Aḥmad b. Ḥamdūn; about the Banū Ḥamdūn; see:

- Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad b. ʿAbdallāh b. Ṭāhir, identified by al-Iṣfahānī as the nephew of ʿUbaydallāh b. ʿAbdallāh b. Ṭāhir (d. 300/913), is the son of Muḥammad b. ʿAbdallāh b. Ṭāhir (d. 296/908–9), the governor of Khurāsān. See also:

- Al-Iṣfahānī mentions a conversation between his father and Muḥammad b. Khalaf b. al-Marzubānī and notes the long-term friendship and marital tie between the two families; see: I owe this reference to: Muḥammad b. Khalaf b. al-Marzubān is a ubiquitous informant in the Aghānī; see:

- The Ṭālibid informants of al-Iṣfahānī comprise: ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAlī b. Ḥamza; ʿAlī b. Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad; ʿAlī b. Muḥammad b. Jaʿfar; Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad b. Jaʿfar; Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. Ḥamza; see:

- al-Iṣfahānī’s uncle, al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad, mentioned in the Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām, either settled in Baghdad with him or at least active for some time there; see:

- About Ibn ʿUqd, see also:

- Compare, for instance, his teacher, al-Ṭabarī.

- It has to be kept in mind that the categorisation is based on the attributives given by al-Iṣfahānī. Just as al-Iṣfahānī was not a local Iṣfahānī, the subjects discussed here do not necessarily engage with the professions their nisbas indicate.

- See also the footnotes above:

- See Legacy, below

- For the few references by al-Iṣfahānī to his administrative tasks, see:

- It is noteworthy that the first sentence of this quote is written differently from the works given here in al-Khaṭīb’s Tārīkh.

- Among the frequently cited sources in the Aghānī is Ḥabīb b. Naṣr al-Muhallabī (d. 307/919), presumably from the Muhallabid family, but it is not clear how this informant relates to Abū Muḥammad al-Muhallabī; see:

- See discussion below, the section on Legacy

- See also:

References

- M. Nallino (1960). "Abu 'l-Faradj al-Isbahani". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 118. OCLC 495469456.

- Bagley, F. R. C. "ABU'L-FARAJ EṢFAHĀNĪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- Sawa, S.G. (1985), "The Status and Roles of the Secular Musicians in the Kitāb al-Aghānī (Book of Songs) of Abu al-Faraj al-Iṣbahānī", Asian Music, 17 (1), Asian Music, Vol. 17, No. 1: 68–82, doi:10.2307/833741, JSTOR 833741

- Sawa 1989, p. 29. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSawa1989 (help)

- Abū Nuʿaym, Akhbār, vol. 2, p. 22. sfn error: no target: Akhbār (help)

- Ibn al-Nadīm, al-Fihrist, p. 128. sfn error: no target: al-Fihrist (help)

- al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām, vol. 13, p. 338; vol. 2, p. 213 (On Ibn Abī al-Fawāris). sfn error: no target: Tārīkh_Madīnat_al-Salām (help)

- al-Hamawī, Muʿjam al-udabāʾ, vol. 13, p. 95–97. sfn error: no target: Muʿjam_al-udabāʾ (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Adab al-ghurabāʾ, p. 83–86. sfn error: no target: al-ghurabā (help)

- Azarnoosh 1992, p. 733. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAzarnoosh1992 (help)

- Günther 2007. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGünther2007 (help)

- al-Munajjid 1972, p. 10–16. sfn error: no target: CITEREFal-Munajjid1972 (help)

- Kilpatrick 2004, p. 230–242. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKilpatrick2004 (help)

- Kilpatrick 1978, p. 127–135. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKilpatrick1978 (help)

- Hoyland 2006, p. 36–39. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHoyland2006 (help)

- Crone & Moreh 2000, p. 128–143. sfn error: no target: CITEREFCroneMoreh2000 (help)

- al-Aṣmaʿī 1951, p. 81–85. sfn error: no target: CITEREFal-Aṣmaʿī1951 (help)

- al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām, vol. 2, p. 213–214. sfn error: no target: Tārīkh_Madīnat_al-Salām (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 68–69. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- De Slane, Mac Guckin (1842). Ibn Khallikan's Biographical Dictionary, Volume 3. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. p. 300.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Abulfaraj". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 79.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Abulfaraj". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 79.

- Kilpatrick 2003, p. vii. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKilpatrick2003 (help)

- al-Ziriklī 2002, vol. 4, p. 278. sfn error: no target: CITEREFal-Ziriklī2002 (help)

- Rotter 1977, p. 7. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRotter1977 (help)

- Amīn 2009, p. 248–249. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAmīn2009 (help)

- Sallūm 1969, p. 9. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSallūm1969 (help)

- Azarnoosh 1992, p. 719. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAzarnoosh1992 (help)

- Khalafallāh 1962, p. 23–25. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKhalafallāh1962 (help)

- Azarnoosh 1992, p. 720. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAzarnoosh1992 (help)

- Ibn al-Nadīm, al-Fihrist, p. 127. sfn error: no target: al-Fihrist (help)

- ^ al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām, vol. 13, p. 337. sfn error: no target: Tārīkh_Madīnat_al-Salām (help)

- ^ al-Dhahabī, Siyar, p. 2774. sfn error: no target: Siyar (help)

- ^ al-Qifṭī, Inbāh, vol. 2, p. 251. sfn error: no target: Inbāh (help)

- ^ Ibn Ḥazm, Jamharat ansāb al-ʿarab, p. 107. sfn error: no target: Jamharat (help)

- Su 2018a, p. 421–422. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSu2018a (help)

- Su 2018a, p. 422–423. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSu2018a (help)

- Su 2018a, p. 424–426. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSu2018a (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Maqātil, p. 547. sfn error: no target: Maqātil (help)

- Su 2018a, p. 426–430. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSu2018a (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Kitāb al-Aghānī, vol. 12, p. 29; vol. 14, p. 113, 157; vol. 16, p. 317–318; vol. 19, p. 35, 49; vol. 20, p. 116. sfn error: no target: al-Aghānī (help)

- Khalafallāh 1962, p. 52–58. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKhalafallāh1962 (help)

- Ibn al-Nadīm, al-Fihrist, p. 143–144. sfn error: no target: al-Fihrist (help)

- van Ess 2017, vol. 1, p. 236. sfn error: no target: CITEREFvan_Ess2017 (help)

- Crone 2005, p. 72, 99. sfn error: no target: CITEREFCrone2005 (help)

- Khalafallāh 1962, p. 58. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKhalafallāh1962 (help)

- Kilpatrick 2003, p. 15. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKilpatrick2003 (help)

- Azarnoosh 1992, p. 728. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAzarnoosh1992 (help)

- al-Hamawī, Muʿjam al-udabāʾ, vol. 4, p. 147–149. sfn error: no target: Muʿjam_al-udabāʾ (help)

- Su 2018a, p. 433–441. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSu2018a (help)

- Su 2018a, p. 431–432. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSu2018a (help)

- ^ al-Iṣfahānī, Kitāb al-Aghānī, vol. 23, p. 21. sfn error: no target: al-Aghānī (help)

- ^ Su 2018a, p. 421–432. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSu2018a (help)

- Su 2018a, p. 429–430. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSu2018a (help)

- Khalafallāh 1962, p. 41–51. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKhalafallāh1962 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 29, 133. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 38, 40, 68–69. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2012. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2012 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 54–56. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Sellheim 2012. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSellheim2012 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 32, 64–65. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Kitāb al-Aghānī, vol. 9, p. 229. sfn error: no target: al-Aghānī (help)

- Ibn al-Nadīm, al-Fihrist, p. 167. sfn error: no target: al-Fihrist (help)

- Leder 2012. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLeder2012 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 30. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Ibn al-Nadīm, al-Fihrist, p. 161. sfn error: no target: al-Fihrist (help)

- Vadet 2012. sfn error: no target: CITEREFVadet2012 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 69. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Kitāb al-Aghānī, vol. 21, p. 48. sfn error: no target: al-Aghānī (help)

- Zetterstéen 2012. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZetterstéen2012 (help)

- Bosworth, Marín & Smith 2012. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBosworthMarínSmith2012 (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Kitāb al-Aghānī, vol. 24, p. 37. sfn error: no target: al-Aghānī (help)

- Kilpatrick 2003, p. 17. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKilpatrick2003 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 58–59. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Günther 1991, p. 140–141; 141–144; 150; 161–162; 190–191.

- al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām, vol. 8, p. 440. sfn error: no target: Tārīkh_Madīnat_al-Salām (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 34–35. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 46–47. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 41–42. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 58. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Kitāb al-Aghānī, vol. 13, p. 25; vol. 14, p. 46–50. sfn error: no target: al-Aghānī (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Kitāb al-Aghānī, vol. 17, p. 157. sfn error: no target: al-Aghānī (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Kitāb al-Aghānī, vol. 24, p. 67. sfn error: no target: al-Aghānī (help)

- Azarnoosh 1992, p. 721. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAzarnoosh1992 (help)

- ^ Kilpatrick 2003, p. 18. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKilpatrick2003 (help)

- Günther 1991, p. 127–131.

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 36–37. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Su 2016, p. 204–209. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSu2016 (help)

- Brown 2008, p. 55–58. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBrown2008 (help)

- Bosworth 2012. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBosworth2012 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 41–42 (al-Akhfash); 60–61 (Ibn Durayd); 32 (Ibn Rustam); 30 (ʿAbd al-Malik al-Ḍarīr). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 42 (Dhukāʾ Wajh al-Ruzza); 34 (Jaḥẓa). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 52–53 (ʿĪsā b. al-Ḥusayn al-Warrāq); 40 (ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn al-Warrāq); 37 (Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Ṣaḥḥāf); 31 (ʿAbd al-Wahhāb b. ʿUbayd al-Ṣaḥḥāf); 65 (Muḥammad b. Zakariyyā al-Ṣaḥḥāf). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 32 (Abū al-Qāsim al-Shīrbābakī). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 32 (Aḥmad b. al-ʿAbbās al-Muʾaddib); 35 (Aḥmad b. ʿImrān al-Muʾaddib); 61–62 (Muḥammad b. al-Ḥusayn al-Muʾaddib); 62 (Muḥammad b. ʿImrān al-Muʾaddib). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 43–44 (Jaʿfar b. Qudāma al-Kātib); 50–51 (al-Ḥusayn b. al-Qāsim al-Kawkabī al-Kātib); 53 (Isḥāq b. al-Ḍaḥḥāk al-Kātib); 41 (ʿAlī b. Ṣāliḥ al-Kātib); 39 (ʿAlī b. al-ʿAbbās al-Ṭalḥī al-Kātib); 39–40 (ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Kātib); 49 (al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad al-Kātib); 57 (Muḥammad b. Baḥr al-Iṣfahānī al-Kātib). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 61 (Muḥammad b. Ḥusayn al-Kindī was al-Iṣfahānī’s tutor and the preacher at the congregational mosque in Qādisiyya); 40–41 (ʿAlī b. Muḥammad, an imam of a Kūfan mosque). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, Kitāb al-Aghānī, vol. 15, p. 255; vol. 19, p. 38; vol. 20, p. 163; vol. 21, p. 158. sfn error: no target: al-Aghānī (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 30 (ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Dāwūd al-Sijistānī); 36–37 (Ibn ʿUqda); 58 (Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī); 59–60 (Muḥammad b. Khalaf Wakīʿ). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 42 (ʿĀṣim b. Muḥammad al-Shāʿir); 49 (al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad al-Shāʿir). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 37 (Aḥmad b. Sulaymān al-Ṭūsī); 37–38 (Ibn ʿAmmār); 42–43 (Abū Khalīfa al-Jumaḥī); 45–46 (al-Ḥaramī b. Abī al-ʿAlāʾ). sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- al-Hamawī, Muʿjam al-udabāʾ, vol. 13, p. 129–130. sfn error: no target: Muʿjam_al-udabāʾ (help)

- Khalafallāh 1962, p. 168–169. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKhalafallāh1962 (help)

- al-Aṣmaʿī 1951, p. 73–85. sfn error: no target: CITEREFal-Aṣmaʿī1951 (help)

- ʿĀṣī 1993, p. 24–30. sfn error: no target: CITEREFʿĀṣī1993 (help)

- al-Tanūkhī, al-Faraj, vol. 2, p. 334. sfn error: no target: al-Faraj (help)

- al-Tanūkhī, Nishwār, vol. 1, p. 18. sfn error: no target: Nishwār (help)

- al-Hamawī, Muʿjam al-udabāʾ, vol. 13, p. 110–111. sfn error: no target: Muʿjam_al-udabāʾ (help)

- Stern 2012. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStern2012 (help)

- Azarnoosh 1992, p. 726–727. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAzarnoosh1992 (help)

- al-Tawḥīdī, Akhlāq al‑wazīrayn, p. 421–422. sfn error: no target: Akhlāq_al‑wazīrayn (help)

- Ibn Khallikān, Wafayāt, vol. 3, p. 307. sfn error: no target: Wafayāt (help)

- al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām, vol. 13, p. 339. sfn error: no target: Tārīkh_Madīnat_al-Salām (help)

- al-Hamawī, Muʿjam al-udabāʾ, vol. 13, p. 105. sfn error: no target: Muʿjam_al-udabāʾ (help)

- Fleischhammer 2004, p. 44. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFleischhammer2004 (help)

- al-Thaʿālibī, Yatīmat, vol. 3, p. 127–131. sfn error: no target: Yatīmat (help)

- al-Iṣfahānī, al-Imāʿ al-shawāʿir, p. 23. sfn error: no target: al-shawāʿir (help)

- al-Hamawī, Muʿjam al-udabāʾ, vol. 13, p. 100. sfn error: no target: Muʿjam_al-udabāʾ (help)

- al-Tanūkhī, Nishwār, vol. 1, p. 74. sfn error: no target: Nishwār (help)

- al-Hamawī, Muʿjam al-udabāʾ, vol. 13, p. 101–103. sfn error: no target: Muʿjam_al-udabāʾ (help)

- al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām, vol. 13, p. 340. sfn error: no target: Tārīkh_Madīnat_al-Salām (help)

- Kilpatrick 2003, p. 19. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKilpatrick2003 (help)

- ^ Al-A'zami, p. 192. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAl-A'zami (help)

- Chambers Biographical Dictionary, ISBN 0-550-18022-2, page 5

- Brünnow 1888. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBrünnow1888 (help)

- Günther, p. 13. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGünther (help)

- Günther, p. 14. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGünther (help)

- Nagel, pp. 258–262. sfn error: no target: CITEREFNagel (help)

- Al-A'zami, Muhammad Mustafa (2003), The History of The Qur'anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation: A Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments, UK Islamic Academy, ISBN 978-1872531656

- Abu’l Faraj al-Isfahani (1888), Brünnow, Rudolf-Ernst (ed.), The Twenty-First Volume of Kitāb al-Aġānī; a Collection of Biographies not contained in the edition of Bulāq, Edited from Manuscripts in the Royal Library of Munich, Toronto: Lidin Matba' Bril

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Günther, Sebastian (1991), Quellenuntersuchungen zu den Maqātil aṭ-Ṭālibiyyīn des Abū 'l-Faraǧ al-Iṣfahānī, Hildesheim

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tilman Nagel (1970). "Ein früher Bericht über den Aufstand von Muḥammad b. ʿAbdallāh im Jahr 145 h". Der Islam (in German) (46 ed.).

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- 897 births

- 967 deaths

- 9th-century Arabs

- 10th-century Arabs

- 10th-century biographers

- 10th-century historians

- 10th-century non-fiction writers

- 10th-century writers

- Scholars of the Abbasid Caliphate

- Arab historians

- Arabic-language poets

- Persian Arabic-language poets

- Muslim encyclopedists

- People from Isfahan

- Poets of the Abbasid Caliphate

- People of the Hamdanid emirate of Aleppo

- 9th-century Arabic poets

- Sayf al-Dawla