This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 2001:984:2ed5:0:1cad:1f52:a4d9:6c6e (talk) at 23:47, 14 March 2022 (→See also: Added links). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:47, 14 March 2022 by 2001:984:2ed5:0:1cad:1f52:a4d9:6c6e (talk) (→See also: Added links)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Use of metasyntactic variables in computer programming Not to be confused with FUBAR or Foobar2000. "Foo" redirects here. For other uses, see Foo (disambiguation).The terms foobar (/ˈfuːbɑːr/), foo, bar, baz, and others are used as metasyntactic variables and placeholder names in computer programming or computer-related documentation. They have been used to name entities such as variables, functions, and commands whose exact identity is unimportant and serve only to demonstrate a concept.

History and etymology

It is possible that foobar is a playful allusion to the World War II-era military slang FUBAR (Fucked Up Beyond All Repair).

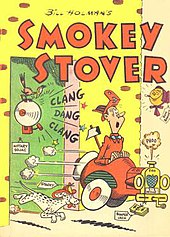

According to an Internet Engineering Task Force RFC, the word FOO originated as a nonsense word with its earliest documented use in the 1930s comic Smokey Stover by Bill Holman. Holman states that he used the word due to having seen it on the bottom of a jade Chinese figurine in San Francisco Chinatown, purportedly signifying "good luck". If true, this is presumably related to the Chinese word fu ("福", sometimes transliterated foo, as in foo dog), which can mean happiness or blessing.

The first known use of the terms in print in a programming context appears in a 1965 edition of MIT's Tech Engineering News. The use of foo in a programming context is generally credited to the Tech Model Railroad Club (TMRC) of MIT from circa 1960. In the complex model system, there were scram switches located at numerous places around the room that could be thrown if something undesirable was about to occur, such as a train going full-bore at an obstruction. Another feature of the system was a digital clock on the dispatch board. When someone hit a scram switch, the clock stopped and the display was replaced with the word "FOO"; at TMRC the scram switches are, therefore, called "Foo switches". Because of this, an entry in the 1959 Dictionary of the TMRC Language went something like this: "FOO: The first syllable of the misquoted sacred chant phrase 'foo mane padme hum.' Our first obligation is to keep the foo counters turning." One book describing the MIT train room describes two buttons by the door labeled "foo" and "bar". These were general-purpose buttons and were often repurposed for whatever fun idea the MIT hackers had at the time, hence the adoption of foo and bar as general-purpose variable names. An entry in the Abridged Dictionary of the TMRC Language states:

Multiflush: stop-all-trains-button. Next best thing to the red door button. Also called FOO. Displays "FOO" on the clock when used.

Foobar was used as a variable name in the Fortran code of Colossal Cave Adventure (1977 Crowther and Woods version). The variable FOOBAR was used to contain the player's progress in saying the magic phrase "Fee Fie Foe Foo". Intel also used the term foo in their programming documentation in 1978.

Examples in language

- Foo Camp is an annual hacker convention.

- BarCamp, an international network of user-generated conferences

- During the United States v. Microsoft Corp. trial, some evidence was presented that Microsoft had tried to use the Web Services Interoperability organization (WS-I) as a means to stifle competition, including e-mails in which top executives including Bill Gates referred to the WS-I using the codename "foo".

- foobar2000 is an audio player.

- Google uses a web tool called "foobar" to recruit new employees.

See also

References

- ^ RFC 3092 - Etymology of "Foo"

- ^ "What does foo mean?". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- Eastlake, D; Manros, C; Raymond, E. "Etymology of "Foo"". The Internet Engineering Task Force. Retrieved 2016-04-17.

- "The History of Bill Holman". Smokey Stover. 2007-06-13. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- Mieke Matthyssen, "Chinese happiness: A proverbial approach ot popular philosophies of life", p. 190, ch. 9 in, Gerda Wielander, Derek Hird (eds), Chinese Discourses on Happiness, Hong Kong University Press, 2018 ISBN 9888455729.

- Tech Engineering News. Vol. 47. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1965. p. 63.

Further, it is possible to search for an effective address; e.g., if an instruction such as "add 1 foo" were used, specifying indirect addressing thru location "foo", and location "foo" contained the address of location "foobar", then an effective word search for "foobar" would find location "foo" and the location containing the "add" instruction as well.

- "Computer Dictionary Online"., computer-dictionary-online.org

- "Abridged Dictionary of the TMRC Language". Tech Model Railroad Club of MIT. Archived from the original on 2018-01-02. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- MCS-86 Assembler Operating Instructions For ISIS-II Users (A32/379/10K/CP ed.). Santa Clara, California, USA: Intel Corporation. 1978. Manual Order No. 9800641A. Retrieved 2020-02-29.

- Mike Ricciuti (2002-07-04). "Microsoft ploy to block Sun exposed". CNET. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- Alistair Charlton (2015-08-27). "Google Foobar: How searching the web earned a software graduate a job at Google". International Business Times. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

External links

- The Jargon File entry on "foobar", catb.org

- RFC 1639 – FTP Operation Over Big Address Records (FOOBAR)