This is an old revision of this page, as edited by AnomieBOT (talk | contribs) at 19:30, 13 March 2022 (Fixing reference errors). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:30, 13 March 2022 by AnomieBOT (talk | contribs) (Fixing reference errors)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "John Ostrom" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| John Ostrom | |

|---|---|

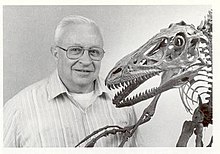

John Ostrom and Deinonychus skeleton cast. Photo courtesy Yale University. John Ostrom and Deinonychus skeleton cast. Photo courtesy Yale University. | |

| Born | (1928-02-18)February 18, 1928 New York City, New York |

| Died | July 16, 2005(2005-07-16) (aged 77) Litchfield, Connecticut |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Yale Columbia Union College |

| Known for | The "Dinosaur renaissance" |

| Awards | Hayden Memorial Geological Award (1986) Romer-Simpson Medal (1994) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Paleontology |

| Doctoral students | Robert T. Bakker Thomas Holtz |

John Harold Ostrom (February 18, 1928 – July 16, 2005) was an American paleontologist who revolutionized modern understanding of dinosaurs in the 1960s.

As first proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in the 1860s, Ostrom showed that dinosaurs were more like big non-flying birds than they were like lizards (or "saurians"), and even proved that birds themselves are a type of theropod saurischian dinosaur. Since dinosaurs themselves are considered reptiles, Ostrom’s work made zoologists question if birds should be considered an order of Reptilia instead of their own class, Aves.

The first of Ostrom's broad-based reviews of the osteology and phylogeny of the primitive bird Archaeopteryx appeared in 1976. His reaction to the eventual discovery of feathered dinosaurs in China, after years of acrimonious debate, was bittersweet.

Early life and career

Ostrom was born in New York in 1928 and grew up in Schenectady. As a pre-medical undergraduate student at Union College, he originally aimed to prepare for medical school in order to become a physician like his father. However, an elective course in geology and George Gaylord Simpson's book The Meaning of Evolution inspired him to change his career plans, and he earned his bachelor's degree in geology in 1951. As an undergraduate and then as a research assistant during the 1950s, he learned about vertebrate paleontology from Simpson and Edwin H. Colbert at the American Museum of Natural History.

Ostrom enrolled at Columbia University as a graduate student under his advisor Ned Colbert, and earned his Ph.D. in 1960 with a thesis on North American hadrosaurs that was based on the skull collection housed at the AMNH. In 1952 he married Nancy Grace Hartman (d. 2003) and they had two daughters, Karen and Alicia.

Ostrom taught for one year at Brooklyn College in 1955 before joining the faculty at Beloit College the following year. In 1961 he accepted a professorship at Yale University, where he remained throughout his career. As a new professor at Yale, Ostrom was named the assistant curator for vertebrate paleontology at the Peabody Museum of Natural History, and became Curator Emeritus in 1971. Throughout his career, Ostrom led and organized fossil-hunting expeditions to Wyoming and Montana, edited the American Journal of Science, published over a dozen books for both popular and lay audiences, and was the recipient of numerous awards and honors. He retired from Yale in 1992, but continued his writing and research there until his health failed. Ostrom died from complications of Alzheimer's disease in July 2005 at the age of 77 in Litchfield, Connecticut.

Key discoveries

In the field of paleontology, Ostrom is responsible for the following key discoveries:

Warm-blooded Deinonychus

His 1964 discovery of additional Deinonychus fossils is considered one of the most important fossil finds in history. Deinonychus was an active predator that clearly killed its prey by leaping and slashing or stabbing with its "terrible claw", the meaning of the animal’s genus name. Evidence of a truly active lifestyle included long strings of muscle running along the tail, making it a stiff counterbalance for jumping and running. The conclusion that at least some dinosaurs had a high metabolism, and were thus in some cases warm-blooded, was popularized by his student Robert T. Bakker. This helped to change the impression of dinosaurs as the sluggish, slow, cold-blooded lizards which had prevailed since the turn of the century.

The implications of Deinonychus changed depictions of dinosaurs both by professional illustrators and as perceived by the public eye. The find is also credited with triggering the "dinosaur renaissance", a term coined in a 1975 issue of Scientific American by Bakker to describe the renewed debates causing an influx of interest in paleontology. The "renaissance" has lasted from the 1970s to the present and has doubled recorded dinosaur diversity.

Archaeopteryx and the origin of flight, and hadrosaur herds

Ostrom's interest in the dinosaur-bird connection started with his study of what is now known as the Haarlem Archaeopteryx. Discovered in 1855, it was actually the first specimen recovered but, incorrectly labeled as Pterodactylus crassipes, it languished in the Teylers Museum in the Netherlands, until Ostrom's 1970 paper (and 1972 description) correctly identified it as one of only eight "first birds" (counting the solitary feather).

Ostrom's reading of fossilized Hadrosaurus trackways also led him to the conclusion that these duckbilled dinosaurs traveled in herds.

Cultural influence

John Ostrom's work on the functional morphology of dinosaurs found that the claws and tendon scars in the tail would indicate a running position. And so the whole posture of bipedal dinosaurs changed to one of agile, fast-running, fearsome predators. This inspired a new generation of dinosaur movies and also museums worldwide changed their dinosaur bone displays.

In 1966 John H. Ostrom was instrumental in the establishment of Dinosaur State Park in Rocky Hill, Connecticut ("because the governor was besieged by letters from schoolchildren swayed into dino-mania by Ostrom").

Dinosaur dig sites

John Ostrom set up a full-time dig site at the Big Horn Basin, Wyoming in the 1960s, as well he spent a lot of time digging at Rocky Hill.

Scientific classification

- In 1970, John Ostrom gave Microvenator celer its formal name (meaning "fast small hunter").

- Also in 1970, he named Tenontosaurus tilletti (meaning "tendon lizard").

- In 1993, James Kirkland, Robert Gaston, and Donald Burge named a fossil Utahraptor ostrommaysorum for John Ostrom and Chris Mays. The largest discovered example of this species is 23 feet long and had an estimated live weight over 1000 pounds.

- In 1998, Catherine Forster named a fossil Rahonavis ostromi (meaning "Ostrom's menace from the clouds") in honour of John Ostrom. The fossil is that of a primitive winged creature with a two-foot wingspan, feathers and a sickle-shaped claw on its second toe designed for slashing prey, similar to Deinonychus and Archaeopteryx.

- In 2017, Ostromia (a new genus named for the Haarlem specimen, formerly of Archaeopteryx) was named in his honor.

References

Notes

- Feduccia, Alan 1999. The origin and evolution of birds. Yale University Press, p55. ISBN 0-300-07861-7

- Heilmann G. 1926. The origin of birds. London: Witherby.

- At last, his theory flies. May 5, 2001. Olivia F. Gentile. Hartford Courant.

- Wilford, John Noble (21 July 2005). "John H. Ostrom, Influential Paleontologist, Is Dead at 77". The New York Times. New York.

- ^ Gates, Alexander E. (2003). A to Z of Earth Scientists. Notable Scientists. New York: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 193–195. ISBN 0-8160-4580-1.

- Curie, Philip J.; Padian, Kevin (1997). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. United States: Elsevier Science. pp. xxix–xxx. ISBN 9780080494746.

- Courant, Hartford. "OSTROM, DR. JOHN H." courant.com. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- Cite error: The named reference

NYwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Schudel, Matt (July 22, 2005). "Dinosaur Expert John Ostrom Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- Dromaeosauridae

- Carlson, Barbara (July 23, 2005). "BRINGING SHALE TO LIFE". courant.com. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

Sources

- "Archaeopteryx" at the Wayback Machine (archived May 27, 2006). May 1975. John H. Ostrom. Discovery, volume 11, number 1, pages 15 to 23.

- Obituary Los Angeles Times July 21, 2005