This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Lordknowle (talk | contribs) at 22:56, 28 February 2007 (This is NOT Link Spam - it is a link to the present day Order.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:56, 28 February 2007 by Lordknowle (talk | contribs) (This is NOT Link Spam - it is a link to the present day Order.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Part of a series on the |

| Knights Templar |

|---|

|

|

Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon |

| Overview |

| Councils |

| Papal bulls |

|

| Locations |

| Successors |

| Cultural references |

| See also |

|

|

The History of the Knights Templar incorporates about two centuries during the Middle Ages, from the Order's founding in the early 1100s, to when it was disbanded in the early 1300s.

Rise

The Knights Templar trace their origin back to shortly after the First Crusade. In 1119, a French nobleman from the Champagne region, Hughes de Payens, collected eight of his knight relatives, and began the Order, their stated mission to protect pilgrims in the Holy Land. They approached King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, and were allowed to set up headquarters on the southeastern side of the Temple Mount, inside the Al Aqsa Mosque.

The Temple Mount is sacred to the Jews, Christians, and Muslims, as an important location throughout history. It is believed to be the location of the ruins of the Temple of Solomon, the legendary storage place for the Ark of the Covenant, and the probable Mount Moriah, where the Biblical Abraham is said to have come to sacrifice his son. It is also an important location to Muslims. At that location in the 7th Century, Caliph Abd al-Malik had built a major Islamic shrine, the Dome of the Rock, at the center of which was the rock from which Muhammad had briefly ascended to heaven to receive the Islamic prayers. The Crusaders turned this into a church, calling it the "Templum Domini", and it was from this that they took their name of Templar. The structure became the model for many subsequent Templar churches in Europe, such as the Temple Church in London, and is represented on several Templar seals.

Little was heard of the Order for their first nine years. In 1128 though, they started to become very well-known in Europe. They went on a fundraising campaign, asking for donations of money, land, or noble-born sons to join the Order, with the implication that donations would help both to defend Jerusalem, and to ensure the charitable giver of a place in Heaven. Their efforts were helped by leading churchman Bernard of Clairvaux (later Sainted), a nephew of one of the original nine, who became the Order's powerful patron. Bernard wrote a multi-page letter entitled "In Praise of the New Knighthood", championing:

- is truly a fearless knight, and secure on every side, for his soul is protected by the armor of faith, just as his body is protected by the armor of steel. He is thus doubly-armed, and need fear neither demons nor men.

De Payens and Bernard participated in the 1128 Council of Troyes, where the Order was officially recognized and confirmed, and the donations came pouring in. For example, in the 1130s, The King of Aragón, in Spain, left large tracts of land to the order upon his death. These generous donations became a common practice for new members. Since the order was first and foremost a monastic organization, new members were expected to donate land, horses and any other items of material wealth, including labor from serfs, as part of their vow of poverty.

In 1139, even more power was conferred upon the Order by Pope Innocent II, who issued an edict known as a Papal Bull. It stated that the Knights Templar could pass freely through any border, owed no taxes, and were subject to no one's authority except that of the Pope. It was a remarkable confirmation of power, which may have been brought about by the Order's patron, Bernard of Clairvaux, who had helped bring Pope Innocent to power.

Warriors

The Knights Templar were the elite fighting force of their day. However, not all of them were warriors. The mission of most of the members was one of support -- to acquire resources which could be used to fund and equip the small percentage of members who were fighting on the front lines. Because of this infrastructure, the warriors were well-trained and very well-armed. Even their horses were trained to fight in combat, kicking or biting the enemies.

The Templars were also shrewd tacticians, following the dream of Saint Bernard who had declared that a small force, under the right conditions, could defeat a much larger enemy. One of the key battles in which this was demonstrated was in 1177, at the Battle of Montgisard. The famous Muslim military leader Saladin was attempting to push toward Jerusalem from the south, with a force of 26,000 soldiers. He had pinned the forces of Jerusalem's King Baldwin IV, about 500 knights and their supporters, near the coast, at Ascalon. Eighty Templar knights and their own entourage attempted to reinforce. They met Saladin's troops at Gaza, but were considered too small a force to be worth fighting, so Saladin turned his back on them and headed with his army towards Jerusalem.

Once Saladin and his army had moved on, the Templars were able to join King Baldwin's forces, and together they proceeded north along the coast. Saladin had made a key mistake at that point -- instead of keeping his forces together, he permitted his army to temporarily spread out and pillage various villages on their way to Jerusalem. The Templars took advantage of this low state of readiness to launch a surprise ambush directly against Saladin and his bodyguard, at Montgisard near Ramla. Saladin's army was spread too thin to adequately defend themselves, and he and his forces were forced to fight a losing battle as they retreated back to the south, ending up with only a tenth of their original number. The battle was not the final one with Saladin, but it bought a year of peace for the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the victory became a heroic legend.

The Templars, though relatively small in number, routinely joined other armies in key battles. They would be the force that would ram through the enemy's front lines at the beginning of a battle, or the fighters that would protect the army from the rear. They fought alongside King Louis VII of France, and King Richard I of England. In addition to battles in Palestine, members of the Order also fought in the Spanish and Portuguese Reconquista. The headquarters of the Templars in Tomar, Portugal, was in the Convento de Cristo.

Bankers

When members joined the Order, they often donated large amounts of cash or property, since all had to take oaths of poverty. Combined with massive grants from the Pope, the Order's financial power was assured from the beginning. Since the Templars kept cash in all their chapter houses and temples, it was natural that in 1135 the Order started lending money to Spanish pilgrims who wanted to travel to the Holy Land.

By 1150, the Order's original mission of guarding pilgrims had changed into a mission of guarding their valuables through an innovative way of issuing letters of credit, an early precursor of modern banking. Pilgrims would visit a Templar house in their home country, depositing their deeds and valuables. The Templars would then give them an encrypted letter which would describe their holdings. While traveling, the pilgrims could present the letter to other Templars along the way, to "withdraw" funds from their account. This kept the pilgrims safe since they were not carrying valuables, and further increased the power of the Templars.

The Knights' involvement in banking grew over time into a new basis for money, as Templars became increasingly involved in banking activities. One indication of their powerful political connections is that the Templars' involvement in usury did not lead to more controversy within the Order and the church at large. Officially the idea of lending money in return for interest was forbidden by the church, but the Order sidestepped this with clever loopholes, such as a stipulation that the Templars retained the rights to the production of mortgaged property. Or as one Templar researcher put it, "Since they weren't allowed to charge interest, they charged rent instead."

Though impressive, their holdings were necessary to support their campaigns; in 1180, a Burgundian noble required 3 square kilometres of estate to support himself as a knight, and by 1260 this had risen to 15.6 km². The Order potentially supported up to 4,000 horses and pack animals at any given time, if provisions of the rule were followed; these horses had extremely high maintenance costs due to the heat in Outremer, and had high mortality rates due to both disease and the Turkish bowmen strategy of aiming at a knight's horse rather than the knight himself. In addition, the high mortality rates of the knights in the East (regularly ninety percent in battle, not including wounded) resulted in extremely high campaign costs due to the need to recruit and train more knights. In 1244, at the battle of La Forbie, where only thirty-three of 300 knights survived, it is estimated the financial loss was equivalent to one-ninth of the entire Capetian yearly revenue.

The Templars' political connections and awareness of the essentially urban and commercial nature of the Outremer communities naturally led the Order to a position of significant power, both in Europe and the Holy Land. They owned large tracts of land both in Europe and the Middle East, built churches and castles, bought farms and vineyards, were involved in manufacturing and import/export, had their own fleet of ships, and for a time even owned the entire island of Cyprus. The Knights Templar were literally part of the fabric of everyday society in Europe for nearly 200 years.

Decline

Their success attracted the concern of many other orders and eventually that of the nobility and monarchs of Europe as well, who were at this time seeking to monopolize control of money and banking after a long chaotic period in which civil society, especially the Church and its lay orders, had dominated financial activities.

Their long-famed military acumen also began to stumble. On July 4, 1187 came the disastrous Battle of the Horns of Hattin, a turning point in the Crusades. It again involved Saladin, who had been beaten back by the Templars in 1177 in the legendary Battle of Montgisard near Tiberias, but this time Saladin was better-prepared. Further, the Grand Master of the Templars was involved in this battle, Gerard de Ridefort, who had just achieved that lifetime position a few years earlier. He was not known as a good military strategist, and he made some deadly errors, such as venturing out with his force of 80 knights without adequate supplies or water, under the devastating desert sun. The Templars were overcome by the desert heat within a day, and then surrounded and massacred by Saladin's army. Ridefort then made a further error which was destined to demoralize the entire Templar Order -- rather than fighting to the death as was the Templar mandate, he was captured, and allowed himself to be ransomed by surrendering Gaza to Saladin. Ridefort then tried to attack Saladin's forces again a few months later at the Siege of Acre, but this too ended in failure and capture, only this time he was beheaded.

The battle marked a turning point in the Crusades, and within a short time the Muslims had re-taken Jerusalem. This shook the foundation of the Templars, whose entire reason for being had been to support the efforts in the Holy Land. They attempted to drum up more support among European nobility to return to battle, but after the fallibility shown by Grand Master Gerard de Ridefort, the French withdrew their own support of the war. Without the support of other countries, even the remarkable leadership of King Richard the Lion-Hearted could not prevail. In one disastrous battle in 1244, 348 Templars were wounded, and 312 killed. Europe had lost interest in pursuing the losing battles of the Crusades. The Order of the Templars became an Order without a clear purpose or support, but which still had enormous financial power. This unstable situation contributed to their downfall.

Fall

The final fall of the Templars may have started over the matter of a loan. The young Philip IV, King of France (also known as "Philip the Fair") had needed cash for his wars and asked the Templars for more money. They refused. The King assigned himself the right to tax the French clergy, and he tried to get the Pope to excommunicate the Templars, but Pope Boniface VIII refused, instead issuing a Papal Bull in 1302 to reinforce that the Pope had absolute supremacy over earthly power, even above a king, and excommunicated King Philip instead. The king responded by sending his councillor, Guillaume de Nogaret, in a plot to kidnap the Pope from his castle in Anagni in September 1303, charging him with dozens of trumped-up charges such as sodomy and heresy. This outrageous incident inspired Dante Aligheri in his Divine Comedy: the new Pilate has imprisoned the Vicar of Christ. The people of Anagni rose up and rescued the aged Boniface VIII, but he died only a month later from shock due to the ill treatment.

His successor, Benedict XI, lifted the excommunication of Philip IV but refused to absolve de Nogaret, excommunicating him and all the other Italian kidnap co-conspirators on June 7, 1304. However, Benedict died just eight months later in Perugia, perhaps from poisoning by an agent of Nogaret. There followed a year of dispute among the French and Italian cardinals as to the next Pope, before deciding on the non-Italian Bertrand de Goth (Clement V), a childhood friend of Philip, in June 1305. Clement withdrew the Papal Bulls of Boniface VIII which had conflicted with Philip IV's plans, created nine more French cardinals, and, after a failed attempt to unite the Templars and the Hospitallers, agreed to Philip IV's demands for an investigation of the Templars. Pope Clement also later moved the papacy from the Italian Anagni to the more palatable (and controllable) French Avignon, initiating the period called the Babylonian Captivity.

On Friday, October 13, 1307, 69 Knights Templar in France were simultaneously arrested by agents of King Philip, later to be tortured into admitting heresy in the Order. Over 100 charges were issued against them, the majority of them identical charges to what had been earlier issued against the inconvenient Pope Boniface VIII. The dominant view is that Philip, who seized the treasury and broke up the monastic banking system, was jealous of the Templars' wealth and power, frustrated by his debt to them, and sought to control their financial resources for himself, by bringing blatantly false information against them at the Tours assembly in 1308; it is also likely that, under the influence of his advisors, he actually believed many of the false charges to be true.

These events, and the Templars' original banking of assets for suddenly mobile depositors, were two of many shifts towards a system of military fiat back to European money, removing this power from Church orders. Seeing the fate of the Templars, the Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem and of Rhodes were also convinced to give up banking at this time. Much of the Templar property outside of France was transferred by the Pope to the Knights Hospitaller, and many surviving Templars were also accepted into the Hospitallers.

Dismantling

In 1312, after the Council of Vienne, and under extreme pressure from King Philip IV, Pope Clement V issued an edict officially dissolving the Order. Many kings and nobles who had been supporting the Knights up until that time, finally acquiesced and dissolved the orders in their fiefs in accordance with the Papal command. Most, however, were not so brutal as the French. In England many Knights were arrested and tried, but not found guilty. And a few Templars had a relative safehaven in Scotland, since Robert the Bruce, the King of Scots, had already been excommunicated for other reasons, and was therefore not disposed to pay heed to Papal commands. The order continued to exist in Portugal, its name was changed to the Order of Christ, and was believed to have contributed to the first naval discoveries of the Portuguese. Prince Henry the Navigator led the Portuguese order for 20 years until the time of his death. In Spain, where the king of Aragon was also against giving the heritage of the Templars to Hospitallers (as commanded by Clement V), the Order of Montesa took Templar assets.

Even with the absorption of Templars into other Orders, there are still questions as to what became of all of the tens of thousands of Templars across Europe. There had been 15,000 "Templar Houses", and an entire fleet of ships. Even in France where hundreds of Templars had been rounded up and arrested, this was only a small percentage of the estimated 3,000 Templars in the entire country. Also, the extensive archive of the Templars, with detailed records of all of their business holdings and financial transactions, was never found. It is unknown if it was destroyed, or moved to another location. Some scholars believe that some of the Templars fled into the Swiss Alps, as there are records of Swiss villagers around that time suddenly becoming very skilled military tacticians. It is also possible that the Templars' financial skills may have become the foundation for what is today the powerful and secretive Swiss banking sector.

Little is known about what became of the Templar's fleet of ships, either. There is record of 18 Templar ships being in port at La Rochelle, France on October 12, 1307 (the day before Friday the 13th). But the next day, they were all gone.

Charges of heresy

Debate continues as to whether the accusation of religious heresy had merit by the standards of the time. Under torture, some Templars admitted to homosexual acts, and to the worship of heads and a mystery known as Baphomet. Their leaders later denied these admissions, and for that were executed. Some scholars discount these as forced admissions, typical during the Inquisition. The majority of charges were identical to other people being tortured by the Inquisitors, with one exception -- head worship. Many Templars were specifically charged with worshipping some type of severed head -- a charge which was issued only against Templars, and never against others.

Some scholars argue that these accusations were in reality due to a misunderstanding of arcane rituals held behind closed doors which had their origins in the Crusaders' bitter struggle against the Saracens. The charges included spitting, trampling, or urinating on the cross; while naked, being kissed obscenely by the receptor on the lips, navel, and base of the spine; heresy and worship of idols; institutionalized homosexuality; and also accusations of contempt of the Holy Mass and denial of the sacraments. According to some scholars, and recently recovered Vatican documents, these acts were intended to simulate the kind of humiliation and torture that a Crusader might be subjected to if captured by the Saracens. According to this line of reasoning, they were taught how to commit apostasy with the mind only and not with the heart.

As for the accusation of head-worship, historical evidence suggests that it referred to rituals involving the alleged relics of John the Baptist, Saint Euphemia, one of Saint Ursula's eleven maidens, and Hughes de Payens rather than pagan idols.

The accusation of venerating Baphomet (which was and still is widely-interpreted as an Old French bastardization of the name Mohammed) is more problematic. Some scholars, such as Hugh J. Schonfield, argue that the chaplains Templar created the term Baphomet through the Atbash cipher to encrypt the gnostic term Sophia (Greek for "wisdom") due to Essene influence rather than subscribing to the dominant opinion that a select few Templars secretly converted to Hashshashin Islam. Regardless which hypothesis is correct, the Baphomet mystery is seen as possibly the only legitimate evidence of isolated heresy within the ranks of the Knights Templar.

Roman Catholic Church's position

It is the Roman Catholic Church's position that the persecution was unjust; that there was nothing inherently wrong with the Order or its Rule; and that the Pope at the time was pressured into suppressing them by public scandal and royal influence. The Church's response at the time corroborates this position. The papal process started by Pope Clement V, to investigate both the Order as a whole and its members individually found virtually no knights guilty of heresy outside of France. Fifty-four knights were executed in France by French authorities as relapsed heretics after denying their original testimonies before the papal commission; these executions were motivated by Philip's desire to prevent Templars from mounting an effective defence of the Order. It failed miserably, as many members testified against the charges of heresy in the ensuing papal investigation.

Despite the poor defense of the Order, when the papal commission ended its proceedings on June 5, 1311, it found no evidence that the Order itself held heretical doctrines, or used a "secret rule" apart from the Latin and French rules. On October 16, 1311, at the General Council of Vienne held in Dauphiné, the council voted for the maintenance of the Order.

But on March 22, 1312, Clement V promulgated the bull Vox in excelsis in which he stated that although there was not sufficient reason to condemn the Order, for the common good, the hatred of the Order by Philip IV, the scandal brought about by their trial, and the likely dilapidation of the Order that would to result from the trial, the Order was to be suppressed by the pope’s authority over it. But the order explicitly stated that dissolution was enacted, "with a sad heart, not by definitive sentence, but by apostolic provision."

This was followed by the papal bull Ad Providum on May 2, 1312, which granted all of the Order's lands and wealth to the Hospitallers so that its original purpose could be met, despite Philip's wishes that the lands in France pass to him. Philip held onto some lands until 1318, and in England the crown and nobility held a great deal until 1338; in many areas of Europe the land was never given over to the Hospitaller Order, instead taken over by nobility and monarchs in an attempt to lessen the influence of the Church and its Orders. Of the knights who had not admitted to the charges, against those whom nothing had been found, or those who had admitted but been reconciled to the Church, some joined the Hospitallers (even staying in the same Templar houses); others joined Augustinian or Cistercian houses; and still others returned to secular life with pension. In Portugal and Aragon, the Holy See granted the properties to two new Orders, the Order of Christ and the Order of Montesa respectively, made up largely of Templars in those kingdoms. In the same bull, he urged those who had pleaded guilty be treated “according to the rigours of justice.“

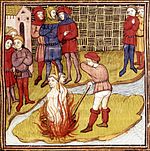

In the end, the only three accused of heresy directly by the papal commission were Jacques de Molay, Grand Master of the Knights Templar, and his two immediate subordinates; they were to renounce their heresy publicly, when de Molay regained his courage and proclaimed the order's and his innocence along with Geoffrey de Charney. The two were arrested by French authorities as relapsed heretics and burned at the stake in 1314. Their ashes were then ground up and dumped into the Seine, so as to leave no relics behind.

It is also worth noting that in no other dominion of Europe were accusations leveled as had been made in France by Philip IV, who was also coincidentally in terrible financial debt to the Templars. So widely was the injustice of Philip's rage against the Templars perceived that the "Curse of the Templars" became legend: Reputedly uttered by the Grand Master Jacques de Molay upon the stake whence he burned, he adjured: "Within one year, God will summon both Clement and Philip to His Judgment for these actions." The fact that both rulers died within a year, as predicted, only heightened the scandal surrounding the suppression of the Order.

Modern perspective

In 1867, a team from the Royal Engineers, led by Lieutenant Charles Warren (later the London police commissioner of Jack the Ripper fame) and financed by the Palestine Exploration Fund (P.E.F.), discovered a series of tunnels beneath Jerusalem and the Temple Mount, some of which were directly underneath the Templar headquarters. Various small artifacts were found which indicated that Templars had used some of the tunnels, though it is unclear who exactly first dug them. Some of the ruins which Warren discovered came from centuries earlier, and other tunnels which his team discovered had evidently been used for a water system, as they led to a series of cisterns., .

Definitive absolution

In 2002, Dr. Barbara Frale found a copy of the Chinon Parchment in the Vatican Secret Archives, a document which indicated that Pope Clement V secretly absolved the leaders of the Order in 1308. She published her findings in the Journal of Medieval History in 2004 Template:Ref harvard.

In modern popular culture, the Templars are remembered in childrens tales, such as The Horn of Roland, or, more recently, in the popular novel, The Da Vinci Code; however, this book lays blame for Templar collapse at the feet of the Catholic church.

References and further reading

- Frale, Barbara (2004). "The Chinon charter - Papal absolution of the last Templar, Master Jacques de Molay". Journal of Medieval History. 30 (2): 109–134.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)

- Malcolm Barber, The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple. Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-42041-5

- Malcolm Barber, The Trial of the Templars, Second edition. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006 (hardback, ISBN 0-521-85639-6; paperback, ISBN 0-521-67236-8)

- Alan Butler, Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers: A History of the Knights Templar from 1307 to the present, Templar Books, 1998. ISBN 0-9683567-2-9

- Sean Martin, The Knights Templar: History & Myths, 2005. ISBN 1-56025-645-1

- Helen Nicholson, The Knights Templar: A New History, Sutton Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7509-2517-5

- Peter Partner, The Knights Templar and their Myth, Destiny Books; Reissue edition, 1990. ISBN 0-89281-273-7

- Dr. Karen Ralls, The Templars and the Grail, Quest Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8356-0807-7

- Piers Paul Read, The Templars, Phoenix Press, 1990. ISBN 0-75381-087-5

- George Smart, The Knights Templar: Chronology, Authorhouse, 2005. ISBN 1-4184-9889-0

- The History Channel, Decoding the Past: The Templar Code documentary, 2005

External links

- Grand Priory of the Knights Templar Official Website of the Grand Priory of Knights Templar in England and Wales

- Knights Templar Catholic Encyclopedia entry

- Templar History Magazine Popular history of the Templars

- Interview with Mark Amaru Pinkham, Grand Prior of the International Order Gnostic Templars. History of the Templars, Holy Grail legends, more.

- Lost Worlds: Knights Templar, July 10, 2006, video documentary on The History Channel