This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Cdjp1 (talk | contribs) at 19:36, 4 January 2023 (→Nancy Qian). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:36, 4 January 2023 by Cdjp1 (talk | contribs) (→Nancy Qian)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Question of whether the 1932–1933 famine in Ukraine constituted genocide This article is about the question of whether the Holodomor constituted genocide. For the question of whether it occurred and minimization of its impact, see Denial of the Holodomor. For the opinions and beliefs about the Holodomor among nations, see Holodomor in modern politics.

| This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. Please help summarize the quotations. Consider transferring direct quotations to Wikiquote or excerpts to Wikisource. (April 2022) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Holodomor |

|---|

Historical backgroundFamines in the Soviet Union

Policies |

|

Responsible partiesSoviet Union |

| Investigation and understanding |

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

|

| Issues |

| Related topics |

| Category |

In 1932–1933, a famine known as the Holodomor killed 3.3–5 million people in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, included in a total of 5.5–8.7 million killed by the broader Soviet famine of 1932–1933. At least 3.3 million ethnic Ukrainians died as a result of the famine in the Soviet Union. Scholars debate "whether the man-made Soviet famine was a central act in a campaign of genocide," or whether it was intended to drive Ukrainian peasants into "collectives and ensure a steady supply of grain for Soviet industrialization."

According to historian Simon Payaslian, the scholarly consensus classifies the Holodomor as a genocide, whereas historian J. Arch Getty had stated in 2000 that the scholarly consensus classified the Holodomor as the result of bungling and rigidity rather than a genocidal plan. Other scholars say it remains a significant issue in modern politics and dispute whether Soviet policies would fall under the legal definition of genocide. Scholars who reject the argument that state policy in regard to the famine was genocide do not absolve Joseph Stalin or any other parts of the Soviet regime as a whole from guilt for the famine deaths, and may still view such policies as being ultimately criminal in nature.

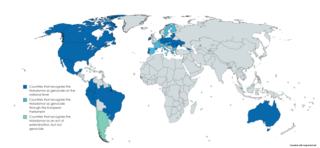

Since 2006, political campaigns have sought recognition of the Holodomor as a genocide, and, as of 2022, over 20 countries and the European Union have recognised the Holodomor as a genocide.

Publications before the dissolution of the USSR

James Mace

Professor of political science James Mace helped British historian Robert Conquest complete the book The Harvest of Sorrow, and after that he was the only U.S. historian working on the Ukrainian famine, and the first to categorically name it as a genocide, while Soviet archives remained closed and without direct evidence of the authorities' intent. In his 1986 article "The man-made famine of 1933 in Soviet Ukraine" written before the archives were opened in 1987, Mace wrote:

For the Ukrainians the famine must be understood as the most terrible part of a consistent policy carried out against them: the destruction of their cultural and spiritual elite which began with the trial of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine, the destruction of the official Ukrainian wing of the Communist Party, and the destruction of their social basis in the countryside. Against them the famine seems to have been designed as part of a campaign to destroy them as a political factor and as a social organism.

Mace, staff director for the U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine, compiled a 1988 Report to Congress, he stated that, based on anecdotal evidence, the Soviets had purposely prevented Ukrainians from leaving famine-struck regions; this was later confirmed by the discovery of Stalin's January 1933 secret decree "Preventing the Mass Exodus of Peasants who are Starving", restricting travel by peasants after "in the Kuban and Ukraine a massive outflow of peasants 'for bread' has begun", that "like the outflow from Ukraine last year, was organized by the enemies of Soviet power." Roman Serbyn called this document one of the "smoking gun revelations about the genocide." One of the nineteen main conclusions of the Report to Congress was that "Joseph Stalin and those around him committed genocide against Ukrainians in 1932–1933."

Robert Conquest

In 1986, British historian Robert Conquest published The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror-Famine, dealing with the collectivization of agriculture in Ukraine and elsewhere in the Soviet Union under Stalin's direction in 1929–1931 and the resulting famine, in which millions of peasants died due to starvation, deportation to labor camps, and execution. In this book, Conquest supported the view that the famine was a planned act of genocide. According to historians Stephen Wheatcroft and R. W. Davies, "Conquest holds that Stalin wanted the famine ... and that the Ukrainian famine was deliberately inflicted for its own sake." Wheatcroft, a rival of Conquest, claims that in unpublished 2003 correspondence Conquest recanted his view that "Stalin purposely inflicted the 1933 famine. No. What I argue is that with resulting famine imminent, he could have prevented it, but put 'Soviet interest' other than feeding the starving first thus consciously abetting it." This assertion about Conquest from his scholarly opponent contradicts published statements Conquest made just 4 years prior directly disputing Wheatcroft's views, writing, "Wheatcroft takes it that Stalin did not 'consciously plan' the famine. 'Plan' is a slippery word: what we are saying is that he consciously inflicted it."

John Archibald Getty

Historian John Archibald Getty, in a critique of The Harvest of Sorrow, which asserted Conquest's original claim that the famine constituted a genocide, states that the conclusion of the famine being engineered is a tempting one but that it is poorly supported by and requires a highly stretched interpretation of the evidence, but that Stalin nonetheless was the entity most responsible for the disaster, citing his role as the prime-backer of hardline collectivisation and excessive demands on the peasantry.

Firstly, Getty calls into question the estimate of the death toll at around five million Ukrainians presented in The Harvest of Sorrow as being much too high, citing much lower demographic estimates from Stephen Wheatcroft, Barbara Anderson, and Brian Silver, and notes that the severity of the famine varied greatly between local regions of Ukraine. Secondly, Getty says that the book fails to provide a convincing motive for genocide, and that other explanations for the famine better fit the evidence than the intentional genocide thesis. Getty points to the fact that Stalin's power was not absolute during these years of his rule, and that he had limited de facto control over local bureaucrats, with many of the Kremlin's orders regarding collectivisation during this time being subverted or ignored at lower levels of the chain of command; in some regions, local bureaucrats exceeded Stalin's demands for expropriation of kulaks, whereas in others, Stalin's demands for expropriation were disregarded and contravened. Moreover, even Stalin's own plans during this time period were frequently unclear and subject to constant change, furthering confusion among the lower bureaucracy and the peasantry; in some districts, farms were collectivised, then decollectivised, and then collectivised yet again within the span of less than a year. Getty also attributes the failure of Soviet authorities to relieve the famine once they realised it was going on to Stalin's paranoia and chaotic decision-making, and that as with his reaction to the German invasion of the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa, the delays by the central government to adequately respond to the crisis stemmed from Stalin's intense distrust even of his own advisors rather than a calculated, deliberate effort to prolong the starvation.

Publications after the dissolution of the USSR

Famine as a genocide

Rafael Lemkin

Rafael Lemkin, who coined the term "genocide" and initiated the Genocide Convention, claimed that Holodomor "is a classic example of the Soviet genocide, the longest and most extensive experiment in Russification, namely the extermination of the Ukrainian nation". Lemkin stated that, because Ukrainian nation was very sensitive to the racial murder of its people and far too populous, this extermination could not follow the pattern of the Holocaust. It instead consisted of four steps:

- Extermination of the Ukrainian national elite, "the brain of the nation", which took place in 1920, 1926 and 1930-1933

- Liquidation of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, "the soul of the nation", which occurred between 1926 and 1932 and during which 10 thousand of its priests were killed

- Extermination of a significant part of the Ukrainian peasantry as "custodians of traditions, folklore and music, national language and literature, and the national spirit" (the Holodomor itself)

- Populating the territory with other nationalities with intent of mixing Ukrainians with them, which would eventually lead to the dissolvance of the Ukrainian nation.

Norman Naimark

Professor of East European studies Norman Naimark states that the Holodomor's deaths were intentional and thus were genocide. In his 2010 book Stalin's Genocides, Naimark wrote:

The Ukrainian killer famine should be considered an act of genocide. There is enough evidence—if not overwhelming evidence—to indicate that Stalin and his lieutenants knew that the widespread famine in the USSR in 1932–33 hit Ukraine particularly hard, and that they were ready to see millions of Ukrainian peasants die as a result. They made no efforts to provide relief; they prevented the peasants from seeking food themselves in the cities or elsewhere in the USSR; and they refused to relax restrictions on grain deliveries until it was too late. Stalin's hostility to the Ukrainians and their attempts to maintain their form of "home rule" as well as his anger that Ukrainian peasants resisted collectivization fueled the killer famine.

Timothy Snyder

Professor of history Timothy Snyder stated that the starvation was "deliberate" and that several of the most lethal policies applied only, or mostly, to Ukraine. In his 2010 book Bloodlands, Snyder stated:

In the waning weeks of 1932, facing no external security threat and no challenge from within, with no conceivable justification except to prove the inevitability of his rule, Stalin chose to kill millions of people in Soviet Ukraine. ... It was not food shortages but food distribution that killed millions in Soviet Ukraine, and it was Stalin who decided who was entitled to what.

In a 2017 Q&A, Snyder said that he believed the famine was genocide but refrained from using the term because it might confuse people, explaining:

If you asked me, is the Ukrainian Holodomor genocide? Yes, in my view, it is. In my view, it meets the criteria of the law of genocide of 1948, the Convention – it meets the ideas that Raphael Lemkin laid down. Is Armenia genocide? Yes, I believe legally it very easily meets that qualification. I just don't think that means what people think it means. Because there are people who hear the word "genocide" and they think it means the attempt to kill every man woman and child, and the Armenian genocide is closer to the Holocaust than most other cases, right, but it's not the same thing. So, I hesitate to use "genocide" because I think every time the word "genocide" is used it provokes misunderstanding.

Andrea Graziosi

According to Italian historian and professor Andrea Graziosi [it], the Holodomor constituted a genocide. And was, "the first genocide that was methodically planned out and perpetrated by depriving the very people who were producers of food of their nourishment"

Graziosi noted that even under the most restrictive definitions of genocide, "deliberately inflicting on members of the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part" is listed as a genocidal act. He also cited the time Lemkin had commented that, “generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation…It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups.”.

Graziosi also emphazized the root of the genocide was "unquestionably a subjective act" which was to use the famine in an "anti-Ukrainian sense on the basis of the 'national interpretation'". Without this, Graziosi said, the death toll would have been at most in the hundreds of thousands.

Nancy Qian

According to a Centre for Economic Policy Research paper published in 2021 by Andrei Markevich, Natalya Naumenko, and Nancy Qian, regions with higher Ukrainian population shares were struck harder with centrally planned policies corresponding to famine such as increased procurement rate, and Ukrainian populated areas were given lower amounts of tractors which the paper argues demonstrates that ethnic discrimination across the board was centrally planned, ultimately concluding that 92% of famine deaths in Ukraine alone along with 77% of famine deaths in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus combined can be explained by systematic bias against Ukrainians. Nancy Qian notes in a lecture about the paper that these results are entirely consistent "with a model of ethnic bias and mass killing" for the famine presented by other authors.

Famine as a crime but not genocide

Robert Davies and Stephen Wheatcroft

Professors R. W. Davies and Stephen G. Wheatcroft state the famine was man-made but unintentional. They believe that a combination of rapid industrialization and two successive bad harvests (1931 and 1932) were the primary reason of the famine. Davies and Wheatcroft agree that Stalin's policies towards the peasants were brutal and ruthless and do not absolve Stalin from responsibility for the massive famine deaths; Wheatcroft says that the Soviet government's policies during the famine were criminal acts of fraud and manslaughter, though not outright murder or genocide. Wheatcroft comments that nomadic and peasant culture was destroyed by Soviet collectivization, which complies with Raphael Lemkin's older concept of genocide, which included cultural destruction as an aspect of the crime, such as that of North American Indians and Australian Aborigines.

In his 2018 article "The Turn Away from Economic Explanations for Soviet Famines", Wheatcroft wrote:

We all agreed that Stalin's policy was brutal and ruthless and that its cover up was criminal, but we do not believe that it was done on purpose to kill people and cannot therefore be described as murder or genocide. ... Davies and I have (2004) produced the most detailed account of the grain crisis in these years, showing the uncertainties in the data and the mistakes carried out by a generally ill-informed, and excessively ambitious, government. The state showed no signs of a conscious attempt to kill lots of Ukrainians and belated attempts that sought to provide relief when it eventually saw the tragedy unfolding were evident. ... But in the following ten years there has been a revival of the 'man-made on purpose' side. This reflects both a reduced interest in understanding the economic history, and increased attempts by the Ukrainian government to classify the 'famine as a genocide'. It is time to return to paying more attention to economic explanations.

Michael Ellman critiqued Davies and Wheatcroft's view of intent as too narrow, stating:

According to them , only taking an action whose sole objective is to cause deaths among the peasantry counts as intent. Taking an action with some other goal (e.g. exporting grain to import machinery) but which the actor certainly knows will also cause peasants to starve does not count as intentionally starving the peasants. However, this is an interpretation of 'intent' which flies in the face of the general legal interpretation.

Robert Conquest

Wheatcroft and Davies noted that Conquest (the author of The Harvest of Sorrow) would later go on to walk back much of the claims made in his earlier book. In a 2003 letter, Conquest clarified to them that "Stalin purposely inflicted the 1933 famine? No. What I argue is that with resulting famine imminent, he could have prevented it, but put "Soviet interest" other than feeding the starving first thus consciously abetting it." In a 2008 interview with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Conquest further stated of the famine that "I don't think the word genocide as such is a very useful one ... the trouble is it implies that somebody, some other nation, or a large part of it were doing it ... But I don't think this is true – it wasn't a Russian exercise, the attack on the Ukrainian people."

Michael Ellman

Professor of economics Michael Ellman states that Stalin clearly committed crimes against humanity but whether he committed genocide depends on the definition of the term. In his 2007 article "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited", he wrote:

Team-Stalin's behaviour in 1930 – 34 clearly constitutes a crime against humanity (or a series of crimes against humanity) as that is defined in the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court article 7, subsection 1 (d) and (h) ... Was Team-Stalin also guilty of genocide? That depends on how 'genocide' is defined. ... The first physical element is the export of grain during a famine. ... The second physical element was the ban on migration from Ukraine and the North Caucasus. ... The third physical element is that 'Stalin made no effort to secure grain assistance from abroad' ... If the present author were a member of the jury trying this case he would support a verdict of not guilty (or possibly the Scottish verdict of not proven). The reasons for this are as follows. First, the three physical elements in the alleged crime can all be given non-genocidal interpretations. Secondly, the two mental elements are not unambiguous evidence of genocide. Suspicion of an ethnic group may lead to genocide, but by itself is not evidence of genocide. Hence it would seem that the necessary proof of specific intent is lacking.

Ellman states that in the end it all depends on the definition of genocide and that if Stalin was guilty of genocide in the Holodomor, then "any other events of the 1917–53 era (e.g. the deportation of whole nationalities, and the 'national operations' of 1937–38) would also qualify as genocide, as would the acts of ", such as the Atlantic slave trade, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the sanctions against Iraq in the 1990s, among many others. Historian Hiroaki Kuromiya finds it persuasive.

Hiroaki Kuromiya

Hiroaki Kuromiya states that although the famine was man-made and much of the deaths could have been avoided had it not been for Stalin's agricultural policies, he finds the evidence for the charge of genocide to be insufficient, and states that it is unlikely that Stalin intentionally caused the famine to kill millions, that he used famine as an alternative to the ethnic deportations that were commonly used as collective punishment under Stalin's rule, or that the famine was specifically engineered to target Ukrainians.

Noting that Stalin had few qualms with killing opponents of his rule and directly ordered several episodes of mass murder, Kuromiya finds the absence of an order to engineer a famine as punishment as unusual, in contrast to the Great Purge and the various deportations and 'national operations' which he personally ordered, and as pointing to the unlikelihood of Stalin deliberately orchestrating mass starvation. He also cites several measures taken by the Soviet government that, although ineffective, provide evidence against the intentionalist thesis, such as nine occasions of curtailing grain exports from different famine-stricken regions and clandestinely purchasing foreign aid to help alleviate the famine. He goes on to suggest that the prioritisation of military food stockpiles over the peasantry was likely motivated by Stalin's paranoia about what he believed to be an impending war with Japan and/or Poland rather than a desire to deliberately starve Ukrainians to death.

Ronald Grigor Suny

Ronald Grigor Suny contrasts the intentions and motivation for the Holodomor and other Soviet mass killings with those of the Armenian genocide. He states that "although on moral grounds one form of mass killing is as reprehensible as another", for social scientists and historians "there is utility in restricting the term 'genocide' to what might more accurately be referred to as 'ethnocide,' that is, the deliberate attempt to eliminate a designated group." His definition of genocide, it "involves both the physical and the cultural extermination of a people."

Suny states that "Stalin's intentions and actions during the Ukrainian famine, no matter what sensationalist claims are made by nationalists and anti-Communists, were not the extermination of the Ukrainian people", and "a different set of explanations is required" for the Holodomor as well as for the Great Purges, the Gulag, and the Soviet ethnic cleansings of minority ethnic groups.

Stephen Kotkin

According to Stephen Kotkin, while "there is no question of Stalin's responsibility for the famine" and many deaths could have been prevented if not for the "insufficient" and counterproductive Soviet measures, there is no evidence for Stalin's intention to kill the Ukrainians deliberately. According to Kotkin, the Holodomor "was a foreseeable byproduct of the collectivization campaign that Stalin forcibly imposed, but not an intentional murder. He needed the peasants to produce more grain, and to export the grain to buy the industrial machinery for the industrialization. Peasant output and peasant production was critical for Stalin's industrialization."

Viktor Kondrashin

Historian Viktor Kondrashin asserts that Stalin's forced collectivisation programme drastically decreased peasants' quality of life and that it was the leading catalyst of the famine, and that although a notable drought did occur in 1931, it and other natural factors were not the primary causes of the famine. However, he rejects the claim that the famine was a targeted genocide of Ukrainians or any other ethnic group in the Soviet Union. According to Kondrashin, in some aspects, conditions for peasants were actually even worse and oppressive laws concerning agriculture even harsher in the Russian regions of the Kuban and Lower Volga, making the genocide thesis untenable in his view. While dismissing the notion that the famine was a genocide, Kondrashin does note, however, that Stalin took advantage of the famine crisis to neutralise the Ukrainian intelligentsia on the pretexts that they were a subversive force behind anti-Soviet uprisings by peasants. Kondrashin also assigns part of the blame for the famine to foreign governments that continued to trade with and buy food from the Soviet Union, in particular the United Kingdom, which imported approximately two million tonnes of Soviet grain during the famine years of 1932 and 1933.

Famine as a result of natural factors

Mark Tauger

Mark Tauger, professor of history at West Virginia University, stated that the 1932 harvest was 30–40% smaller than official statistics and that the famine was "the result of a failure of economic policy, of the 'revolution from above'", not "a 'successful' nationality policy against Ukrainians or other ethnic groups." In his 1991 article "The 1932 Harvest and the Famine of 1933", Tauger wrote:

Western and even Soviet publications have described the 1933 famine in the Soviet Union as "man-made" or "artificial." ... Proponents of this interpretation argue, using official Soviet statistics, that the 1932 grain harvest, especially in Ukraine, was not abnormally low and would have fed the population. ... New Soviet archival data show that the 1932 harvest was much smaller than has been assumed and call for revision of the genocide interpretation. The low 1932 harvest worsened severe food shortages already widespread in the Soviet Union at least since 1931 and, despite sharply reduced grain exports, made famine likely if not inevitable in 1933. ... Thus for Ukraine, the official sown area (18.1 million hectares) reduced by the share of sown area actually harvested (93.8 percent) to a harvested area of 17 million hectares and multiplied by the average yield (approximately 5 centners) gives a total harvest of 8.5 million tons, or a little less than 60 percent of the official 14.6 million tons.

Tauger stated that "the harsh 1932–1933 procurements only displaced the famine from urban areas" but the low harvest "made a famine inevitable." Tauger stated that it is difficult to accept the famine "as the result of the 1932 grain procurements and as a conscious act of genocide" but that "the regime was still responsible for the deprivation and suffering of the Soviet population in the early 1930s", and "if anything, these data show that the effects of were worse than has been assumed."

Davies and Wheatcroft criticized Tauger's methodology in the 2004 edition of The Years of Hunger. Tauger criticized Davies and Wheatcroft's methodology in a 2006 article. In the 2009 edition of their book, Davies and Wheatcroft apologized for "an error in our calculations of the 1932 yield" and stated grain yield was "between 55 and 60 million tons, a low harvest, but substantially higher than Tauger's 50 million." While they disagree on the exact tonnage of the harvest, they reach a similar conclusion as Tauger in their book's most recent edition and state that "there were two bad harvests in 1931 and 1932, largely but not wholly a result of natural conditions", and "in our own work we, like V.P. Kozlov, have found no evidence that the Soviet authorities undertook a programme of genocide against Ukraine. ... We do not think it appropriate to describe the unintended consequences of a policy as 'organised' by the policy-makers."

In a 2002 article for The Ukrainian Weekly, David R. Marples criticized Tauger's choice of rejecting state figures in favour of those from collective farms, where there was an incentive to underestimate yields, and he argued that Tauger's conclusion is incorrect because in his view "there is no such thing as a 'natural' famine, no matter the size of the harvest. A famine requires some form of state or human input." Marples criticized Tauger and other scholars for failing "to distinguish between shortages, droughts and outright famine", commenting that people died in the millions in Ukraine but not in Russia because "the 'massive program of rationing and relief' was selective."

Government recognition

After campaigns from the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the recognition of the Holodomor as a genocide, the governments of various countries have issued statements recognizing the Holodomor as genocide including Ukraine and 14 other countries, as of 2006, including Australia, Canada, Colombia, Georgia, Mexico, Peru and Poland.

In November 2022, the Holodomor was recognized as a genocide by Germany, Ireland, Moldova, Romania, and the Belarusian opposition in exile. Pope Francis compared the Russian war in Ukraine with its targeted destruction of civilian infrastructure to the "terrible Holodomor Genocide", during an address at St. Peter's Square.

Countries recognising Holodomor as a genocide:

Australia, 28 October 1993

Australia, 28 October 1993  Brazil, 26 April 2022

Brazil, 26 April 2022 Canada, 20 June 2003

Canada, 20 June 2003 Colombia, 21 December 2007

Colombia, 21 December 2007 Czech Republic, 6 April 2022

Czech Republic, 6 April 2022 Ecuador, 30 October 2007

Ecuador, 30 October 2007 Estonia, 20 October 1993

Estonia, 20 October 1993 Georgia, 20 December 2005

Georgia, 20 December 2005 Germany, 30 November 2022

Germany, 30 November 2022 Hungary, 26 November 2003

Hungary, 26 November 2003 Ireland, 24 November 2022

Ireland, 24 November 2022 Latvia, 13 March 2008

Latvia, 13 March 2008 Lithuania, 24 November 2005

Lithuania, 24 November 2005 Mexico, 19 February 2008

Mexico, 19 February 2008 Moldova, 24 November 2022

Moldova, 24 November 2022 Paraguay, 25 October 2007

Paraguay, 25 October 2007 Peru, 19 June 2007

Peru, 19 June 2007 Poland, 4 December 2006

Poland, 4 December 2006 Portugal, 2 March 2017

Portugal, 2 March 2017 Romania, 24 November 2022

Romania, 24 November 2022 Ukraine, 28 November 2006

Ukraine, 28 November 2006 United States, 11 December 2018

United States, 11 December 2018 Vatican City, 2 April 2004

Vatican City, 2 April 2004

Other political bodies

EU (European Parliament), 15 December 2022

EU (European Parliament), 15 December 2022

See also

- Assessment of the Kazakh famine of 1931–1933

- Droughts and famines in Russia and the Soviet Union

- Functionalism–intentionalism debate

- Law of Spikelets

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- Outline of Genocide studies

Notes

- "We may well ask whether having revolutionarily high expectations is a crime? Of course it is, if it leads to an increase in the level of deaths, as a result of insufficient care being taken to safeguard the lives of those put at risk when the high ambitions failed to be fulfilled, and especially when it was followed by a cover-up. The same goes for not adjusting policy to unfolding evidence of crisis. But these are crimes of manslaughter and fraud rather than of murder. How heinous are they in comparison, say, with shooting over 600,000 citizens wrongly identified as enemies in 1937-8, or in shooting 25,000 Poles identified as a security risk in 1940, when there was no doubt as to the outcome of the orders? The conventional view is that manslaughter is less heinous than cold blooded murder."

- "However, points out that in terms of the initial definition proposed by Raphael Lemkin there was an attempt to change and replace the essential culture of the indigenous nomadic herdsmen. Therefore, in this other earlier interpretation, it could be argued that the Kazakh nomads faced genocide. This is in the same sense that Russian peasants faced destruction of their culture in the creation of the new Soviet man, and that North American Indians and Australian Aborigines faced cultural destruction at the hands of Soviet, North American, and Australian states."

References

- Snyder (2010), p. 53. "One demographic retrojection suggests a figure of 2.5 million famine deaths for Soviet Ukraine. This is too close to the recorded figure of excess deaths, which is about 2.4 million. The latter figure must be substantially low, since many deaths were not recorded. Another demographic calculation, carried out on behalf of the authorities of independent Ukraine, provides the figure of 3.9 million dead. The truth is probably in between these numbers, where most of the estimates of respectable scholars can be found. It seems reasonable to propose a figure of approximately 3.3 million deaths by starvation and hunger-related disease in Soviet Ukraine in 1932–1933"; Davies & Wheatcroft (2004), p. xiv; Gorbunova & Klymchuk (2020); Ye (2020), pp. 30–34; Marples (2007), p. 246, "Still, the researchers have been unable to come up with a firm figure of the number of victims. Conquest cites 5 million deaths; Werth from 4 to 5 million; and Kul'chyts'kyi 3.5 million."; Mendel (2018), "The data of V. Tsaplin indicates 2.9 million deaths in 1933 alone."; Yefimenko (2021)

- "Resolution of the Kyiv Court of Appeal, 13 January 2010". Retrieved 2 February 2019.

The Conclusions of the forensic court demographic expertise of the Institute of Demography and Social Research of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, dated November 30, 2009, state that 3 million 941 thousand people died as a result of the genocide perpetrated in Ukraine. Of these, 205 thousand died in the period from February to December 1932; in 1933 – 3,598 thousand people died and in the first half of 1934 this number reached 138 thousand people;v. 330, pp. 12–60

- LB.ua 2010. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLB.ua2010 (help)

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2004, p. 401.

- Rosefielde, Steven (September 1996). "Stalinism in Post-Communist Perspective: New Evidence on Killings, Forced Labour and Economic Growth in the 1930s". Europe-Asia Studies. 48 (6): 959–987. doi:10.1080/09668139608412393.

- Wolowyna, Oleh (October 2020). "A Demographic Framework for the 1932–1934 Famine in the Soviet Union". Journal of Genocide Research. 23 (4): 501–526. doi:10.1080/14623528.2020.1834741. S2CID 226316468.

- Snyder 2010, p. 53. "All in all, no fewer than 3.3 million Soviet citizens died in Soviet Ukraine of starvation and hunger-related diseases; and about the same number of Ukrainians (by nationality) died in the Soviet Union as a whole.".

- Yaroslav Bilinsky (June 1999). "Was the Ukrainian famine of 1932–1933 genocide?". Journal of Genocide Research. 1 (2): 147–156. doi:10.1080/14623529908413948. ISSN 1462-3528. Wikidata Q54006926. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019.

- Payaslian, Simon (2019). "20th Century Genocides". Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- Getty, J. Arch (2000). "The Future Did Not Work". The Atlantic.

Similarly, the overwhelming weight of opinion among scholars working in the new archives (including Courtois's co-editor Werth) is that the terrible famine of the 1930s was the result of Stalinist bungling and rigidity rather than some genocidal plan. ... To them the famine of 1932–1933 was simply a planned Ukrainian genocide, although today most see it as a policy blunder that affected millions belonging to other nationalities.

- Marples, David (30 November 2005). "The great famine debate goes on ..." ExpressNews (University of Alberta), originally published in the Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008.

- Kulchytsky, Stanislav (17 February 2007). "Holodomor 1932–1933 rr. yak henotsyd: prohalyny u dokazovii bazi" Голодомор 1932 — 1933 рр. як геноцид: прогалини у доказовій базі [Holodomor 1932–1933 as genocide: gaps in the evidence]. Den (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 19 January 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Ellman, Michael (June 2007). "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited". Europe-Asia Studies. 59 (4). Routledge: 663–693. doi:10.1080/09668130701291899. S2CID 53655536.

- ^ Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (August 2020). "The Complexity of the Kazakh Famine: Food Problems and Faulty Perceptions". Journal of Genocide Research. 23 (4): 593–597. doi:10.1080/14623528.2020.1807143. S2CID 225333205.

- ^ Andriewsky, Olga (23 January 2015). "Towards a Decentred History: The Study of the Holodomor and Ukrainian Historiography". East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 2 (1): 18–52. doi:10.21226/T2301N. ISSN 2292-7956.

On 28 November 2006, the Parliament of Ukraine, with the president's support and in consultation with the National Academy of Sciences, voted to recognize the Ukrainian Famine of 1932–33 as a deliberate act of genocide against the Ukrainian people ("Zakon Ukrainy pro Holodomor"). A vigorous international campaign was subsequently initiated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to have the United Nations, the Council of Europe, and other governments do the same.

- ^ The Kyiv Independent news desk (24 November 2022). "Romania, Moldova, Ireland recognize Holodomor as genocide against Ukrainian people". The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ Dahm, Julia (15 December 2022). "EU parliament votes to recognise 'Holodomor' famine as genocide". Euractiv. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ "International Recognition of the Holodomor". Holodomor Education. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Expressing the sense of the House of Representatives that the 85th anniversary of the Ukrainian Famine of 1932—1933, known as the Holodomor, should serve as a reminder of repressive Soviet policies against the people of Ukraine". United States Congress. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ Andriewsky, Olga (23 January 2015). "Towards a Decentred History: The Study of the Holodomor and Ukrainian Historiography". East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 2 (1). University of Alberta: 18–52. doi:10.21226/T2301N. ISSN 2292-7956.

- Mace, James (1986). "The man-made famine of 1933 in Soviet Ukraine". In Serbyn, Roman; Krawchenko, Bohdan (eds.). Famine in Ukraine in 1932–1933. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. ISBN 9780092862434.

- Martin, Terry (2001). The Affirmative Action Empire : Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939. pp. 306–307.

TsK VKP/b/ and Sovnarkom have received information that in the Kuban and Ukraine a massive outflow of peasants "for bread" has begun into Belorussia and the Central-Black Earth, Volga, Western, and Moscow regions. / TsK VKP/b/ and Sovnarkom do not doubt that the outflow of peasants, like the outflow from Ukraine last year, was organized by the enemies of Soviet power, the SRs and the agents of Poland, with the goal of agitation "through the peasantry" . . . TsK VKP/b/ and Sovnarkom order the OGPU of Belorussia and the Central-Black Earth, Middle Volga, Western and Moscow regions to immediately arrest all "peasants" of Ukraine and the North Caucasus who have broken through into the north and, after separating out the counterrevolutionariy elements, to return the rest to their place of residence. . . . Molotov, Stalin

- Serbyn, Roman (19 November 2007). "Is there a "smoking gun" for the Holodomor?". Unian. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine; James Mace (1988). Investigation of the Ukrainian Famine 1932-1933: Report to Congress (1st ed.). Washington, D.C. ISBN 0-16-003290-3. Wikidata Q105077080.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Robert Conquest – Historian – Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ Davies & Wheatcroft 2004, p. 441.

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2004, p. 441.

- Conquest 1999, p. 1480.

- Getty, John Archibald (22 January 1987). "Starving the Ukraine". London Review of Books. 9 (2). Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- "Holodomor was a genocide, according to the author of the term". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Soviet Genocide in Ukraine". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- Naimark, Norman M. (2010). Stalin's Genocides. Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity. Vol. 12. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14784-0.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9.

- Snyder, Timothy (6 April 2017). The Politics of Mass Killing: Past and Present (Speech). 15th Annual Arsham and Charlotte Ohanessian Lecture and Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Symposium Keynote Address. University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts.

- "Holodomor". University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Graziosi, Andrea (2004). "The Soviet 1931–1933 Famines and the Ukrainian Holodomor: Is a New Interpretation Possible, and What Would Its Consequences Be?". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 27 (1/4): 97–115. ISSN 0363-5570. JSTOR 41036863.

- ^ "Nancy Qian presenting: "The Political Economic Causes of the Soviet Great Famine, 1932-1933"". CEPR & VideoVox Economics. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022 – via YouTube.

- Markevich, Andrei; Naumenko, Natalya; Qian, Nancy (July 2021). "The Political-Economic Causes of the Soviet Great Famine, 1932–33". National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers. doi:10.3386/w29089. SSRN 3928687. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP16408.

- ^ Davies & Wheatcroft 2004.

- ^ Davies, Robert; Wheatcroft, Stephen (June 2006). "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33: A Reply to Ellman" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 58 (4): 625–633. doi:10.1080/09668130600652217. S2CID 145729808 – via JSTOR.

- Wheatcroft, Stephen (2018). "The Turn Away from Economic Explanations for Soviet Famines". Contemporary European History. 27 (3): 465–469. doi:10.1017/S0960777318000358.

- "RFE/RL Interview: Robert Conquest On 'Genocide' And Famine". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 8 December 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Hiroaki, Kuromiya (June 2008). "The Soviet Famine of 1932–1933 Reconsidered". Europe-Asia Studies. 60 (4). Taylor & Francis: 663–675. doi:10.1080/09668130801999912. JSTOR 20451530. S2CID 143876370.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015). "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. pp. 350–54, 456 (note 1). ISBN 978-1-4008-6558-1.

- Lay summary in: Ronald Grigor Suny (26 May 2015). "Armenian Genocide". 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Kotkin, Stephen (8 November 2017). "Terrible Talent: Studying Stalin". The American Interest (Interview). Interviewed by Richard Aldous.

- Nefedov, Sergei; Ellman, Michael (26 June 2019). "The Soviet Famine of 1931–1934: Genocide, a Result of Poor Harvests, or the Outcome of a Conflict Between the State and the Peasants?". Europe-Asia Studies. 71 (6): 1048–1065. doi:10.1080/09668136.2019.1617464. S2CID 198785836. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- "Mark B. Tauger, Associate Professor". Department of History (West Virginia University). Retrieved 10 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Tauger, Mark (1991). "The 1932 Harvest and the Famine of 1933". Slavic Review. 50 (1): 70–89. doi:10.2307/2500600. JSTOR 2500600. S2CID 163767073.

- Wheatcroft, Stephen (2004). "Towards explaining Soviet famine of 1931–3: Political and natural factors in perspective". Food and Foodways. 12 (2): 107–136. doi:10.1080/07409710490491447. S2CID 155003439.

- Tauger, Mark (2006). "Arguing from errors: On certain issues in Robert Davies' and Stephen Wheatcroft's analysis of the 1932 Soviet grain harvest and the Great Soviet famine of 1931–1933". Europe-Asia Studies. 58 (6): 975. doi:10.1080/09668130600831282. S2CID 154824515.

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2004, pp. xix–xxi.

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2004, p. xv.

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2004, pp. xiv–xvii.

- Marples, David (14 July 2002). "Debating the undebatable? Ukraine Famine of 1932–1933". The Ukrainian Weekly. Vol. LXX, no. 28. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ "ZAKON UKRAYINY: Pro Holodomor 1932–1933 rokiv v Ukrayini" ЗАКОН УКРАЇНИ: Про Голодомор 1932–1933 років в Україні [LAW OF UKRAINE: About the Holodomor of 1932–1933 in Ukraine]. rada.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). 28 November 2006. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- Stewart, Daniel (24 November 2022). "Irish Senate recognizes Ukrainian genocide in the 1930s". News 360. MSN. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- "Romania recognizes Holodomor of 1932-1933 in Ukraine as genocide". Ukrinform. 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- "Romania and Belarus' opposition recognized Holodomor as a genocide of Ukrainians". The New Voice of Ukraine. Yahoo! News. 24 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- Pianigiani, Gaia (23 November 2022). "Pope Francis compares Russia's war against Ukraine to a devastating Stalin-era famine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- "The upper house of the Brazilian parliament has recognized the Holodomor as an act of genocide". Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- "Aprovado reconhecimento do Holodomor como genocídio contra ucranianos" [Approved recognition of Holodomor as genocide against Ukrainians]. Senado Federal (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- "The Czech Republic recognized the Holodomor of 1932–1933 as genocide in Ukraine". Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- "Germany recognized the Holodomor with the genocide of the Ukrainian people". 30 November 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- "Ireland's Senate recognizes Holodomor of 1932–1933 in Ukraine as genocide". Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- "Mark Daly". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- "Romania, Moldova, Ireland recognize Holodomor as genocide against Ukrainian people". 24 November 2022. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- "Parlamento de Portugal reconheceu a Holodomor de 1932–1933 na Ucrânia como Genocídio contra o povo Ucraniano". Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- "Romania recognizes Holodomor of 1932–1933 in Ukraine as genocide". Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- "Senat SSHA vyznav Holodomor henotsydom ukrayinsʹkoho narodu" Сенат США визнав Голодомор геноцидом українського народу [The US Senate recognized the Holodomor as genocide of the Ukrainian people]. Ukrainian Pravda (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "Text – H.Res.931 – 115th Congress (2017–2018): Expressing the sense of the House of Representatives that the 85th anniversary of the Ukrainian Famine of 1932–1933, known as the Holodomor, should serve as a reminder of repressive Soviet policies against the people of Ukraine". United States Congress. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "European Parliament recognizes Holodomor as genocide against Ukrainian people". Ukrinform. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

Bibliography

- Conquest, Robert (1999). "Comment on Wheatcroft". Europe-Asia Studies. 51 (8): 1479–1483. doi:10.1080/09668139998426. JSTOR 153839.

- Davies, Robert; Wheatcroft, Stephen (2004). The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1933. The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia. Vol. 5. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230273979. OCLC 1075104809.

- Gorbunova, Viktoriia; Klymchuk, Vitalii (2020). "The Psychological Consequences of the Holodomor in Ukraine". East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 7 (2): 33–68. doi:10.21226/ewjus609. S2CID 228999786.

- Marples, David R. (2007). Heroes and Villains: Creating National History in Contemporary Ukraine. Central European University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-9637326981.

- Mendel, Iuliia (24 November 2018). "85 Years Later, Ukraine Marks Famine That Killed Millions". The New York Times. Gale A563244157.

- Наливайченко назвал количество жертв голодомора в Украине [Nalyvaichenko called the number of victims of Holodomor in Ukraine] (in Russian). LB.ua. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Ye, Kravchenko (2020). "The Concept of Demographic Losses in the Holodomor Studies". Vìsnik – Kiïvsʹkij Nacìonalʹnij Unìversitet Ìmenì Tarasa Ševčenka: Ìstorìâ. 144: 30–34.

- Yefimenko, Hennadiy (5 November 2021). "More is not better. The deleterious effects of artificially inflated Holodomor death tolls". Euromaidan Press. Translated by Chraibi, Christine.

Further reading

- Boriak, H. (2001). The Publication of Sources on the History of the 1932–1933 Famine-Genocide: History, Current State, and Prospects. Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 25(3/4), 167–186.

- Collins, Laura C. "Book Review: The Holodomor Reader: A Sourcebook on the Famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine," Genocide Studies and Prevention (2015) 9#1: 114–115 online.

- Klid, Bohdan and Alexander J. Motyl, eds. The Holodomor Reader: A Sourcebook on the Famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine (2012).

- Kulʹchytsʹkyi, Stanislav. "The Holodomor of 1932–33: How and Why?." East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies 2.1 (2015): 93–116. online

- Moore, Rebekah. "'A Crime Against Humanity Arguably Without Parallel in European History': Genocide and the 'Politics' of Victimhood in Western Narratives of the Ukrainian Holodomor." Australian Journal of Politics & History 58#3 (2012): 367–379.