This is an old revision of this page, as edited by William M. Connolley (talk | contribs) at 22:25, 26 March 2007 (rv stupid tag). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

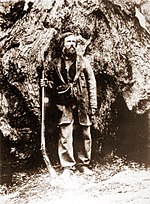

Revision as of 22:25, 26 March 2007 by William M. Connolley (talk | contribs) (rv stupid tag)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)The known history of the Yosemite area started with Ahwahnechee and Paiute peoples who inhabited the central Sierra Nevada region of California that now includes Yosemite National Park. At the time when the first non-indigenous people entered the area, a band of Native Americans called the Ahwahnechee lived in Yosemite Valley. The California Gold Rush in the mid-19th century greatly increased the number of non-indigenous people in the area. Conflict ensued as part of the Mariposa Wars, and the Mariposa Battalion entered Yosemite Valley in 1851 while in pursuit of the Ahwaneechees led by Chief Tenaya. Accounts from this battalion were the first confirmed cases of Caucasians entering the valley.

The Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove were ceded to California as a state park, in 1864, with Galen Clark as its first guardian. Access to the park by tourists improved in the early years of the park and conditions in the Valley were made more hospitable. Naturalist John Muir and others soon became alarmed about over-exploitation of the area, and helped push through the creation of Yosemite National Park in 1890. It would not be until 1906 that the Valley and Grove would be added.

Jurisdiction of the park was first under the United States Army's 4th Cavalry Regiment, and was transferred to the National Park Service in 1916. Many improvements to the park made through this entire time induced dramatic increases in visitation. Controversies did arise along the way; the most notable was the failed fight to save Hetch Hetchy Valley from becoming a reservoir and hydroelectric power plant. Since then, about 94% of the park has been set aside in a highly protected wilderness area, and other protected areas were added adjacent to the park. The once-famous Yosemite Firefall, created by red hot embers being pushed off of a cliff near Glacier Point at night, has been discontinued.

Early history

Humans may have first visited Yosemite as early as 8000 to 10,000 years ago, and people started to settle in Yosemite Valley around 4000 years before the present. In the 11th or 12th century. The band of indigenous people that lived in Yosemite Valley called the valley that provided them with nuts, berries, and small game Ahwahnee (meaning "valley that looks like a gaping mouth") and called themselves the Ah-wah-ne-chee (meaning dwellers in Ahwahnee).

Like humans before and since, the Ahwahnechee changed the Valley to suit their needs. Since the band depended upon acorns for 60% of their diet, they burned vegetation on the Valley floor, which favored Black Oak (an acorn-making tree). Fire management also expanded meadows and reduced brush within woodlands, thus making ambush by invading tribes difficult.

Displaced Native Americans from the coast of California moved to the Sierra Nevada in the early to mid-19th century. They brought their experiences with Spanish food, technology, and clothing as they joined tribes in the mountains. Together they raided ranchos on the coast and drove herds of horses to the Sierra, where horse meat became a major new food source.

Exploration by Europeans

Significant debate still surrounds the issue of who the first non-indigenous person to see the Valley was. In the autumn of 1833, Joseph Reddeford Walker may have seen the Valley; he later described trying to lead his party of trappers across that part of the Sierra Nevada and approaching a valley rim that plunged "more than a mile" (1.6 km). He and his party also happened upon the Tuolumne Grove of Giant Sequoia, becoming the first known non-indigenous people to see the giant trees (they may also have seen the Merced Grove).

The part of the Sierra Nevada where the park is located was long considered to be a physical barrier to non-indigenous settlers, traders, trappers, and travelers. That status changed, in 1848, due to the discovery of gold in the foothills west of the range in the California Gold Rush. Travel and trade activity dramatically increased in the area, competing with the local Native Americans and destroying resources they depended upon. The first reliable sighting of the Valley by a non-indigenous person occurred on October 18, 1849 by William P. Abrams and a companion. Abrams accurately described some landmarks but it is not known for sure whether or not he or his companion actually entered the Valley. In 1850, Joseph Screech became the first confirmed non-indigenous person to enter Hetch Hetchy Valley. He settled there, and noted that the Paiutes inhabited Hetch Hetchy before the coming of the Europeans.

The first intentional and systematic exploration of any part of the Yosemite area backcountry was conducted in 1855 by the surveying crew of Allexey W. Von Schmidt, as part of the Public Land Survey System. Von Schmidt's charge was to establish the Mount Diablo Base Line from the initial point at Mount Diablo east across the Sierra Nevada, preliminary to the General Land Office (GLO) rectangular survey in California and Nevada. This line passes through Tuolumne Meadows and very near the summit of Mount Dana, (although Von Schmidt, for unknown reasons, surveyed his line 5 to 6 miles south of the actual line, which was not surveyed until around 1880). This survey was the first crossing of the Sierra Nevada that did not follow established trails or the natural routes suggested by topography. In 1863-67, the California Geological Survey surveyed parts of Yosemite's high country and the boundary of the new state park. From 1879 to 1883 large areas of the park were contracted for survey by GLO contract surveyors. However, the individual contracted for the largest area, one S.A. Hanson, was associated with the Benson Syndicate, and he combined actual with probably fabricated surveys. In 1878-79 topographic surveys performed by Lieutenant Montgomery Macomb, under George M Wheeler's Surveys West of the 100th Meridian, made use of various peaks in the high country to connect with Wheeler's extensive surveys further east, north and south.

Mariposa Wars and legacy

In 1851 the Mariposa Battalion was created under the authority of the Governor of California to put an end to raids carried out by Native Americans in the Mariposa Wars. Major James Savage led the Battalion into Yosemite Valley in that same year while in pursuit of around 200 Ahwaneechees led by Chief Tenaya who were suspected of raiding trading posts in the area — most notably Savage's. On Thursday March 27 of that year the company of 50 to 60 men reached what is now called Old Inspiration Point and saw the major features of the Valley laid out before them (they named the overlook Mt. Beatitude). Attached to Savage's unit was Dr. Lafayette Bunnell, the company physician who later wrote about his awestruck impressions of the valley in The Discovery of the Yosemite.

While camped at Bridalveil Meadow Bunnell suggested that the Valley be named '"Yo-sem-ity", after what the surrounding Sierra Miwok tribes, who feared the Yosemite Valley tribe, called them. At the time, Savage, who spoke some native dialects, translated this as "full-grown grizzly bear". Later translations found that the actual term, while possibly derived or at least confused with the similar uzumati or uhumati (meaning 'grizzly bear'), was in fact a Southern Sierra Miwok word Yohhe'meti meaning "they are killers". The name stuck even though the tribe they named the valley after called themselves Ahwahnechee.

Bunnell went on to name many other local topographic features on the same trip. Others in the company were also moved by what they saw and recounted their journey to friends and family after they returned, increasing interest in the Valley and surrounding area. Bunnell soon after drafted an article about the trip, but destroyed it when a newspaper correspondent in San Francisco suggested cutting his 1500 foot (460 m) height estimate for the Valley walls in half (the walls are in fact twice the height that Bunnel surmised). So the first published account of the Valley was written by Lt. Tredwell Moore for the January 20, 1854 issue of the Mariposa Chronicle. The modern spelling of Yosemite was established by that article.

Chief Tenaya and his band were eventually captured and their village burned, fulfilling a prophecy an old and dying medicine man gave Tenaya many years before. The Ahwahnechee were escorted by their captor Captain John Bowling to the Fresno River Reservation near Fresno, California. Life on the reservation was unpleasant and the Ahwahneechee longed for their valley, prompting reservation officials to allow Tenaya and some of his band to return on their own recognizance in winter.

A group of eight miners entered the Valley in the Spring of 1852 and were allegedly attacked by Tenaya's warriors, with two of the miners being killed. A second battalion was organized, and executed six Ahwahneechee under the direction of Lt. Moore. Tenaya's band fled the Valley and sought refuge with the Mono, his mother's tribe. In Summer or early Fall of 1853, the Ahwahneechee apparently returned to the Valley, but later betrayed the hospitality of their Mono hosts by stealing some horses that the Mono had taken from non-indigenous ranchers. In return the Monos tracked down and killed many of the remaining Ahwahneechee, including Tenaya. Tenaya Lake is named after the fallen chief. Hostilities then subsided, and by the mid 1850s local non-indigenous residents started to befriend Native Americans living in the Yosemite area.

Mono Paiutes were the only group that kept returning to the Valley on a regular basis. They lived in established native villages in the Valley into the early 20th century. As older tribe members died, younger ones tended to favor non-traditional housing provided by the National Park Service. A few Paiute and Miwok families still live in the Valley and are employed by the Park Service. A reconstructed "Indian Village of Ahwahnee" is now located behind the Yosemite Museum, which is next to the Yosemite Valley Visitor Center. The museum has exhibits that interpret the cultural history of Yosemite's indigenous residents from 1850 to the present. In addition, the museum has regularly scheduled demonstrations of basket-weaving, beadwork, and traditional games by Native American presenters.

Popularization, exploitation, and protection

Artists, photographers, and the first tourists

Entrepreneur James Hutchings, artist Thomas Ayres, and two others ventured into the area in 1855, becoming the Valley's first tourists. After returning to Mariposa Hutchings wrote an article about his experience which appeared in the August 9, 1855 issue of the Mariposa Gazette and was later published in various forms nationally. Ayres' sketch of Yosemite Falls was published in fall that year, and four of his drawings were presented in the lead article of the July 1856 and initial issue of Hutchings' Illustrated California Magazine. These were the first known accurate pictures of Yosemite Valley. Ayres returned in 1856 and visited Tuolumne Meadows in the area's high country. His highly-detailed but angularly-exaggerated artwork and his written accounts were nationally published. An art exhibition of his drawings was later held in New York City.

Hutchings brought photographer Charles Leander Weed to the Valley in 1859. Weed took the first photographs of the Valley's features, and a September exhibition in San Francisco presented them to the public. Hutchings published four installments of "The Great Yo-semite Valley" from October 1859 to March 1860 in his magazine. A book by Hutchings titled Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California collected these articles and the book stayed in print well into the 1870s.

Stanford University mechanical engineering student Arthur Clarence Pillsbury arrived in Yosemite for the first time by bicycle in 1895. The young man fell in love with Yosemite and in 1897 bought a studio there. He visited Yosemite many times and photographed Muir, Galen Clark, George Fiske, and Teddy Roosevelt. These photos were published as postcards by the Pillsbury Picture Company. Pillsbury had begun producing postcards with his photos as soon as this innovative form of communication was authorized by Congress in 1898. His many nature films, eventually shown in theaters as well as in schools, clubs and for his lecture tours awakened the public to the need for conservation in the wake of Muir's death in 1914.

Photographer Ansel Adams was famous for his early 20th century pictures of Yosemite. He willed the originals of his Yosemite photos to the Yosemite Park Association, and visitors can still buy direct prints from his original negatives. The studio in which prints are sold was established in 1902 by artist Harry Cassie Best. Carleton Watkins exhibited his 17x22-inch Yosemite views at the 1867 Paris International Exposition.

In 1856, Milton and Houston Mann (2 of 42 tourists to visit the valley the year before) finished a toll road to the Valley that traveled up the South Fork of the Merced River. Before they were bought out by Mariposa County they charged the then large sum of two dollars per person. Under county control the road was free.

Wawona was an indigenous encampment in what is now the southwestern part of the park. Settler Galen Clark discovered the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia in Wawona in 1856; a year later he completed a bridge over the South Fork Merced in Wawona for traffic inbound to the Valley. Clark also provided a way station for tourists traveling on the road that the Mann brothers built to the Valley. Simple lodgings, later called the Lower Hotel, were completed soon afterward; Upper Hotel (later renamed Hutchings House and now known as Cedar Cottage) was opened in 1858. In 1879, the more substantial Wawona Hotel was built to serve tourists visiting the nearby Grove and those on their way to the Valley (at the time, it took 8 hours to travel from Wawona to the Valley via stage). The Washburns, owners of the hotel, bought Clark's land and covered the bridge he built. A year before the hotel was completed, A. Harris built the first public campground in Yosemite. As tourism increased, the number of trails and hotels also increased.

Early protection efforts and the state park

A Unitarian minister named Thomas Starr King visited the Valley in 1860 and saw some of the negative effects that homesteading and commercial activity were having on the area. Six travel letters by King were published in the Boston Evening Transcript in 1860 and 1861 (Oliver Wendell Holmes and John Greenleaf Whittier read and commented on them). King went on to become the first person with a nationally-recognized voice to call for a public Yosemite park. Pressure by King, photographs by famed photographer Carleton Watkins, and geologic data from the 1863 Geological Survey of California prompted legislators to take notice. But the American Civil War slowed progress by shifting the nation's attention.

Visitation and interest in Yosemite continued through the national crisis, however. Frederick Law Olmsted, the United States' most widely respected landscape architect, became interested by Kings' warnings and visited Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove in 1863 to see for himself. Concerned by what he saw, he convinced Senator John Conness of California to introduce a Park bill in the United States Senate.

The uncontroversial bills passed both houses of the United States Congress and was signed by President Abraham Lincoln on June 30, 1864, creating the Yosemite Grant as a public trust. Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove were ceded to California as a state park for "public use, resort and recreation." A board of Yosemite commissioners was proclaimed by the state's governor September that year, but the body did not convene until 1866 (with Frederick Law Olmsted as chairman).

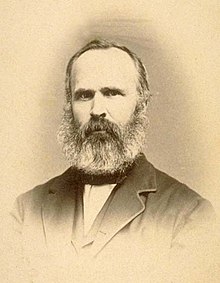

Galen Clark was appointed by the commission as the park's first guardian, but neither Clark nor the commissioners had the authority to evict homesteaders, starting an 11 year struggle. Josiah Whitney, the first director of the California Geological Survey, lamented that Yosemite Valley may become like what Niagara Falls was at the time - a tourist trap where proprietary interests place tolls on every bridge, path, trail, and viewpoint. Previously-mentioned Hutchings was one of a small group that had claims on 160 acres (65 ha) of the valley floor. The issue was not settled until 1875 when the land holdings of Hutchings and three others were invalidated. A State grant of $24,000 for improvements Hutchings made to Upper Hotel helped compensate for his loss. Two years after losing his land, Hutchings published a second Yosemite guide, Hutchings' Tourist Guide to the Yo Semite Valley and the Big Tree Groves.

However, under Clark's on and off stewardship through 1896, access to the park by tourists improved, and conditions in the Valley were made more hospitable to humans. Tourism started to significantly increase after a Sacramento to Stockton extension of the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869 and the Central Pacific Railroad reached Merced in 1872. The long horseback ride needed to reach the area was still a deterrent, so three stagecoach roads were built in the mid-1870s to provide better access to the growing number of visitors to the Valley and Grove;

- Coulterville Road (June 1874)

- Big Oak Flat Road (July 1874)

- Mariposa/Wawona Road (July 1875)

The first stage arrived in July 1874, a road to Glacier Point was completed in 1882 by John Conway, and the Great Sierra Wagon Road was opened in 1883 (roughly following the Mono Trail to Tuolumne Meadows).

Yosemite's oldest concession was established in 1884 when Mr. and Mrs. John Degnan established a bakery and store. Perhaps the most famous concession, the Curry Company, was started by David and Jenny Curry in 1899 (they founded Camp Curry, now known as Curry Village). In 1900 Oliver Lippincott became the first person to drive an automobile into the Valley. Yosemite Valley Railroad, nicknamed "the short line to paradise", arrived at nearby El Portal, California in 1907. Tourists transferred from the railway to stagecoaches that traveled through Merced Canyon to reach Yosemite Valley.

Life on the Valley floor was plagued by mosquitoes and the threat of contracting diseases they carry. So in 1878 Clark used dynamite to breach a recessional moraine in the valley that impounded a swamp behind it. Numerous hiking and horse trails were also cleared, including a walking path through Mariposa Grove.

Clark and the reigning commissioners were ousted in 1880 by the California Legislature and Hutchings became the new park guardian. That same year Bunnell's account of the Valley's discovery was finally published. Hutchings in turn was removed as guardian in 1884 and was replaced by W.E. Dennison. Clark was reappointed as guardian in 1889.

John Muir's influence and the national park

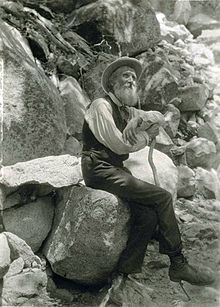

Scotland-born naturalist John Muir first came to California in 1868 and immediately set out for the Yosemite area. Articles written by Muir helped to both popularize the area and increase scientific interest in it. Muir was one of the first to theorize that the major landforms in Yosemite were created by large alpine glaciers, bucking established scientists such as Josiah Whitney who regarded Muir as an amateur (see geology of the Yosemite area). Muir also wrote scientific papers on the area's biology.

Alarmed by over-grazing of meadows (especially by sheep who Muir called "hooved locusts"), logging of Giant Sequoia, and other damage, Muir changed from being a promoter and scientist to an advocate for further protection. As part of this new role he persuaded many influential people to accompany him to camp in the park, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1871. On these trips Muir would try to convince his guests of the importance of putting the area under federal protection. None of his guests through the 1880s could do much for Muir's cause except for Robert Underwood Johnson, who was editor of Century Magazine. Through Johnson, Muir had a national audience for his writing and a highly motivated and crafty Congressional lobbyist.

His wish was partially answered on September 25, 1890 when the area outside the valley and sequoia grove became a national park under the un-opposed Yosemite Act. The Act withdrew these lands from "settlement, occupancy, or sale" and protected "all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities or wonders" along with prohibiting "wanton destruction of the fish and game and their capture or destruction for the purposes of merchandise or profit". This was the first time the federal government set aside land for such a purpose, an act that is widely considered to be genesis of the national park idea. It is important to note, that Yosemite National Park does include the entire upper drainages of two separate river watersheds (which was very important to Muir who said "you cannot save Yosemite Valley without saving its Sierran fountains."). The State of California, however, retained control of the Valley and Grove. Muir also helped persuade local officials to virtually eliminate grazing from the Yosemite High Country. A dairy herd was kept in the valley and all horses brought there grazed in its meadows, however. Muir and 181 others founded the Sierra Club in 1892, in part to lobby for the transfer of the Valley and Grove into the National Park.

Army administration and a unified national park

Like Yellowstone National Park before it, Yosemite was at first administered by the United States Army. Captain Abram Wood led the 4th Cavalry Regiment into the new park on May 19, 1891 and set up camp in Wawona, called Camp A.E. Wood (now the Wawona Campground). Each summer, 150 cavalrymen traveled from the Presidio of San Francisco to patrol the park. A major problem facing the Cavalry were the approximately 100,000 sheep that were illegally led into Yosemite's high meadows by shepherds each year. Lacking the legal authority to arrest the herders, the Cavalry instead escorted the shepherds several days hike away from their flock. This left the sheep vulnerable and thus became an excellent deterrent. By the late 1890s sheep grazing was no longer a problem, but at least one herder continued grazing his sheep in the park into the 1920s.

An extensive trail system developed by the Cavalry later formed the basis for the current trails. To mark trails, the cavalrymen blazed capital Ts into trees, a practice continued from that point onward even though none of the originally blazed trees are still standing.

Galen Clark retired as the state park's guardian in 1896, leaving the Valley and Grove under ineffective stewardship. Pre-existing problems in the state park worsened and new problems arose, but the Cavalry could only monitor the situation. Long a proponent of creating a unified Yosemite national park, Muir and his Sierra Club continued to lobby the government and influential people for the creation of a unified Yosemite National Park. In an effort to make the remote area more accessible, the Sierra Club began organizing annual trips to Yosemite, starting in 1901 (a practice that continues to the present day). The LeConte Memorial Lodge is a National Historic Landmark built in 1902 as an education center in honor of Joseph LeConte, a University of California geologist who died in Yosemite Valley the year before.

Then in May of 1903, Theodore Roosevelt – who was then President of the United States – camped with John Muir near Glacier Point for three days. On that trip, Muir convinced Roosevelt to take control of the Valley and the Grove away from California and give it to the federal government. In 1906 Roosevelt signed a bill that did precisely that, and the Superintendent's headquarters was moved from the Wawona area to Yosemite Valley. In 1905, however, a huge compromise had to be made to get Congressional and State of California approval; the park extent was substantially reduced, excluding much of what is now the Ansel Adams Wilderness. This compromise excluded natural wonders such as Devils Postpile and prime wildlife habitat.

Army administration of the Park ended in 1914 as well as horse-drawn stage service. Two years of minimal civilian stewardship ensued with 15 former cavalry scouts serving as the only rangers. This task was made all the more difficult due to increasing visitation by motorists, which were common by 1914. Park visitation doubled in 1915 to 31,000 (the 1915 entrance fee for motorists was $5, more than an average worker made in a day). In an attempt to keep up with demand, stage service was briefly renewed but ended for good in 1916.

The National Park Service was formed in 1916 and Yosemite was transferred to that agency's jurisdiction with W.B. Lewis as superintendent. Tuolumne Meadows Lodge and Tioga Pass Road, along with campgrounds at Tenaya and Merced lakes, were also completed in 1916. 600 automobiles entered the east side of the Park using Tioga Road that summer. Stephen Mather, the first director of the Park Service, built the "Ranger's Club" at his own expense in 1920 to house Yosemite rangers. Mather donated it to the park and it is now maintained as a National Historic Landmark. In 1926 the "All-Weather Highway" (now California State Route 140) opened, ensuring year-long visitation and supplies under normal conditions. The completion of the 0.8 mile (1.3 km) long Wawona Tunnel in 1933 was both an engineering marvel and significantly reduced the amount of travel time to the Valley from Wawona without scarring the landscape with a long road cut (the famous 'Tunnel View' is on the Valley side of the tunnel and Inspiration Point is above it). A flood, reduced lumber and mining extraction, and greatly increased automobile and bus use forced the Yosemite Valley Railway out of business in 1945. The present day Tioga Road (part of California State Route 120) across the park was dedicated in 1961.

Starting in 1920, the groundwork for interpretive programs and services in national parks was laid in Yosemite by Harold C. Bryant and Loye Holmes, two professors of natural history. The position of park naturalist was created in 1921 with Ansel F. Hall performing that duty for two years. Hall pioneered the idea of having park museums act as public contact centers and general headquarters for interpretive programs - a model followed by all later national parks in the United States and widely adapted internationally as well. Chris Jorgenson's former artist's studio was used to house the temporary museum from 1921 to 1926. Yosemite Museum, the first permanent museum in the National Park System, was completed in 1926.

The fight over Hetch Hetchy Valley

To the north of Yosemite Valley is Hetch Hetchy Valley, which was considered by many, including John Muir, to be nearly identical in beauty and significance to Yosemite Valley. In 1908, however, rights to Hetch Hetchy were granted to the City of San Francisco, which needed a new fresh water supply to help rebuild following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. A long and nationally-polarized fight, pitting preservationists like Muir who wanted to leave wild areas wild against conservationists like Gifford Pinchot who wanted to manage wild areas for the betterment of mankind, ensued. Congress eventually authorized the O'Shaughnessy Dam in 1913 through passage of the Raker Act. The valley was flooded in 1923 by impounding of the Tuolumne River behind the O'Shaughnessy Dam, forming the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. The dam supplies 80% of the drinking water, and some cash from electricity sales, to San Francisco.

Plans are currently being studied for the removal of the dam, and alteration of the Hetch Hetchy water system to compensate for the resulting water loss.

The earliest Native peoples of Hetch Hetchy were Paiutes.

More recent history

The Ahwahnee Hotel, built in 1927 in Yosemite Valley, is a luxury hotel decorated in Native American motifs. It was designed by the architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood who designed lodges at many of the national parks. For many years Ansel Adams produced an annual pageant there, and in World War II it was used as a rehabilitation hospital for soldiers. It is now a National Historic Landmark.

Yosemite National Park has had 11 winter floods since 1916 that have caused substantial damage to property. All of these floods took place between November 1 and January 30. The largest floods occurred in 1937, 1950, 1955, and 1997, and were in the range of 22,000 to 25,000 cubic feet (620 to 700 m³) per second, as measured at the Pohono Bridge gauging station in Yosemite Valley . After the 1950 flood, all structures in Old Yosemite Village, except for the chapel, were either moved to the Pioneer Yosemite History center in Wawona or demolished in the 1950s and 1960s. Other structures from throughout the park were also moved to the history center. Some structures in the Old Village, such as the historic 1858 Cedar Cottage, then the oldest building in Yosemite Valley, were demolished even though they weren't flooded. Back then little regard was given to historic preservation, the thought being that the "highest use" was preserving and restoring natural scenery.

Three different protected zones were added adjacent to Yosemite National Park in 1964:

These additional protected areas include areas removed from Yosemite National Park just prior to the 1906 Act as well as other public land.

A 1964 act of Congress set aside about 94% of the park in a highly protected wilderness area. No roads, motorized vehicles (except rescue helicopters and other emergency vehicles), or any development of any kind beyond trail maintenance are allowed in this area.

In 1968 the famous Yosemite Firefall, in which the embers from a bonfire were pushed off of a cliff near Glacier Point to create a spectacular effect, was ended because it drew excessively large crowds. The Firefall was occasionally performed in the 1870s and became a nightly tradition with the founding of Camp Curry.

The broader tensions in American society were felt in Yosemite in 1970, when a large number of youths gathered in the park over the summer. Rioting broke out on July 4 in Stoneman Meadow. The visitors attacked rangers with rocks and pulled mounted rangers from their horses. The National Guard was brought in to maintain order.

The late 1990s brought a high-profile murder case in the park and some serious rock slides; one rockslide originating from the east side of Glacier Point ended near the Happy Isles of the Merced River, creating a debris field larger than several football fields. Tourism dropped a little after those incidents, but soon after returned to previous levels.

Human impact

The first automobile entered the Valley in 1900, but growth in car traffic did not increase significantly until 1913 when they were first officially allowed to enter. In 1914, 127 cars entered the park.

These changes did not come without consequences or tension between access and preserving the natural surroundings. Visitation rapidly swelled with the advent of the automobile, especially after World War II. Visitation reached 1 million in the 1950s, 2 million in the 1960s, 3 million in the 1980s and 4 million in the 1990s. Car use has proportionately increased too. These millions of users have dramatically influenced the local ecosystem.

Decades of aggressive fire suppression have been replaced by a fire management program that includes the yearly use of prescribed fires. Fire is especially important to the Giant Sequoia groves, whose seeds cannot germinate without fire-touched soil.

In March of 1986 the California Department of Fish and Game, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Forest Service reintroduced Bighorn Sheep just east of the park in Lee Vining Canyon. The herd reached a peak of nearly 100 individuals in 1994, but almost 60% of the herd died in the winter of 1994-1995. About 55 bighorns from the herd were counted in the 1996 census.

Brown Bears, also called grizzlies, were once the top predators in the region but went locally extinct in the 1920s (the particular endemic subspecies, the Golden Bear, went completely extinct). The last confirmed kill of a Yosemite grizzly occurred in Wawona in 1895. These animals figured prominently in Miwok mythology, and a sketch of a Yosemite grizzly by Charles Nahl adorns the flag of California. Inevitable losses of cattle, and danger to people, makes the prospect of reintroduction into the park remote.

Many visitors fail to realize the wild aspect of the park, and tend to treat it like a zoo - feeding animals, petting them, taking mementos home; this is a dramatic safety issue for the visitors and is also illegal. Squirrels that feed all summer become obese, making them prey for Mountain Lions, which are a safety issue unto themselves. Food left in cars are easy pickings for the local Black Bear populations. Petting Mule Deer risks serious injury (the only person killed in Yosemite by an animal was killed by a deer). The Park Service, in conjunction with businesses and groups in the park, are trying to encourage people to experience and learn about Yosemite.

Trails and high use areas are redesigned to reduce impact. A free shuttle bus system has been developed to help relieve summer traffic congestion in the valley. Proposals to exclude cars in the summer that are not registered at a hotel or campsite within the valley have been investigated (this has already been implemented at other parks, such as Zion National Park in Utah). Many agencies in the Park offer educational activities and trips. Ironically, only about 14 square miles (36 km²) of the 1,200 mi² of the park are visited by a majority of the people.

References

Major works cited

- Geology of National Parks: Fifth Edition, Ann G. Harris, Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D., Tuttle (Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing; 1997) ISBN 0-7872-5353-7

- Yosemite: Official National Park Service Handbook (no. 138), Division of Publications, National Park Service

- Yosemite: A Visitors Companion, George Wuerthner, (Stackpole Books; 1994) ISBN 0-8117-2598-7

- Yosemite National Park: A Natural History Guide to Yosemite and Its Trails, Jeffrey P. Schaffer, (Wilderness Press, Berkeley; 1999) ISBN 0-89997-244-6

- The Pioneer Yosemite History Center: A place of pioneers who profoundly influenced the National Park idea, pamphlet, National Park Service and the Yosemite Association.

Notes

- Above California, Retrieved 4 January 2007

- abovecalifornia.com, Retrieved 4 January 2007

- Bunnell, Lafayette (1892). The Discovery of the Yosemite (3rd edition ed.). New York: F.H. Revell Company.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Bunnell, The Discovery of the Yosemite, Section IV, page 62

- Greene, Linda Wedel (September 1987). YOSEMITE: THE PARK AND ITS RESOURCES: A History of the Discovery, Management, and Physical Development of Yosemite National Park, California (volume 1 of 3). U.S. Department of the Interior / National Park Service. p. 22.

- Beeler, Madison Scott (September 1955). "Yosemite and Tamalpais". Names. 55 (3): 185–186.

- Second Tourist Party to Yosemite Valley, Mariposa Gazette, August 9, 1855

- Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California, (1862) by James M. Hutchings

- Yosemite National Park: Water Overview, National Park Service, Retrieved 4 January 2007

External links

- Yosemite: The Embattled Wilderness

- Yosemite Native American discussion board

- Historic Yosemite Indian Chiefs - with photos