This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 93.182.105.236 (talk) at 14:51, 5 June 2024 (Image). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:51, 5 June 2024 by 93.182.105.236 (talk) (Image)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) System for organizing the days of yearthumb|right|A Calendar representing the month of July

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is also a physical record (often paper) of such a system. A calendar can also mean a list of planned events, such as a court calendar, or a partly or fully chronological list of documents, such as a calendar of wills.

Periods in a calendar (such as years and months) are usually, though not necessarily, synchronized with the cycle of the sun or the moon. The most common type of pre-modern calendar was the lunisolar calendar, a lunar calendar that occasionally adds one intercalary month to remain synchronized with the solar year over the long term.

Etymology

The term calendar is taken from kalendae, the term for the first day of the month in the Roman calendar, related to the verb calare 'to call out', referring to the "calling" of the new moon when it was first seen. Latin calendarium meant 'account book, register' (as accounts were settled and debts were collected on the calends of each month). The Latin term was adopted in Old French as calendier and from there in Middle English as calender by the 13th century (the spelling calendar is early modern).

History

Main article: History of calendars Further information: Week, Calendar epoch, Month, Lunisolar calendar, Computus, and Calendar reform

The course of the Sun and the Moon are the most salient regularly recurring natural events useful for timekeeping, and in pre-modern societies around the world lunation and the year were most commonly used as time units. Nevertheless, the Roman calendar contained remnants of a very ancient pre-Etruscan 10-month solar year.

The first recorded physical calendars, dependent on the development of writing in the Ancient Near East, are the Bronze Age Egyptian and Sumerian calendars.

During the Vedic period India developed a sophisticated timekeeping methodology and calendars for Vedic rituals. According to Yukio Ohashi, the Vedanga calendar in ancient India was based on astronomical studies during the Vedic Period and was not derived from other cultures.

A large number of calendar systems in the Ancient Near East were based on the Babylonian calendar dating from the Iron Age, among them the calendar system of the Persian Empire, which in turn gave rise to the Zoroastrian calendar and the Hebrew calendar.

A great number of Hellenic calendars were developed in Classical Greece, and during the Hellenistic period they gave rise to the ancient Roman calendar and to various Hindu calendars.

Calendars in antiquity were lunisolar, depending on the introduction of intercalary months to align the solar and the lunar years. This was mostly based on observation, but there may have been early attempts to model the pattern of intercalation algorithmically, as evidenced in the fragmentary 2nd-century Coligny calendar.

The Roman calendar was reformed by Julius Caesar in 46 BC. His "Julian" calendar was no longer dependent on the observation of the new moon, but followed an algorithm of introducing a leap day every four years. This created a dissociation of the calendar month from lunation. The Gregorian calendar, introduced in 1582, corrected most of the remaining difference between the Julian calendar and the solar year.

The Islamic calendar is based on the prohibition of intercalation (nasi') by Muhammad, in Islamic tradition dated to a sermon given on 9 Dhu al-Hijjah AH 10 (Julian date: 6 March 632). This resulted in an observation-based lunar calendar that shifts relative to the seasons of the solar year.

There have been several modern proposals for reform of the modern calendar, such as the World Calendar, the International Fixed Calendar, the Holocene calendar, and the Hanke–Henry Permanent Calendar. Such ideas are mooted from time to time, but have failed to gain traction because of the loss of continuity and the massive upheaval that implementing them would involve, as well as their effect on cycles of religious activity.

Systems

A full calendar system has a different calendar date for every day. Thus the week cycle is by itself not a full calendar system; neither is a system to name the days within a year without a system for identifying the years.

The simplest calendar system just counts time periods from a reference date. This applies for the Julian day or Unix Time. Virtually the only possible variation is using a different reference date, in particular, one less distant in the past to make the numbers smaller. Computations in these systems are just a matter of addition and subtraction.

Other calendars have one (or multiple) larger units of time.

Calendars that contain one level of cycles:

- week and weekday – this system (without year, the week number keeps on increasing) is not very common

- year and ordinal date within the year, e.g., the ISO 8601 ordinal date system

Calendars with two levels of cycles:

- year, month, and day – most systems, including the Gregorian calendar (and its very similar predecessor, the Julian calendar), the Islamic calendar, the Solar Hijri calendar and the Hebrew calendar

- year, week, and weekday – e.g., the ISO week date

Cycles can be synchronized with periodic phenomena:

- Lunar calendars are synchronized to the motion of the Moon (lunar phases); an example is the Islamic calendar.

- Solar calendars are based on perceived seasonal changes synchronized to the apparent motion of the Sun; an example is the Persian calendar.

- Lunisolar calendars are based on a combination of both solar and lunar reckonings; examples include the traditional calendar of China, the Hindu calendar in India and Nepal, and the Hebrew calendar.

- The week cycle is an example of one that is not synchronized to any external phenomenon (although it may have been derived from lunar phases, beginning anew every month).

Very commonly a calendar includes more than one type of cycle or has both cyclic and non-cyclic elements.

Most calendars incorporate more complex cycles. For example, the vast majority of them track years, months, weeks and days. The seven-day week is practically universal, though its use varies. It has run uninterrupted for millennia.

Solar

Main article: Solar calendarSolar calendars assign a date to each solar day. A day may consist of the period between sunrise and sunset, with a following period of night, or it may be a period between successive events such as two sunsets. The length of the interval between two such successive events may be allowed to vary slightly during the year, or it may be averaged into a mean solar day. Other types of calendar may also use a solar day.

The Egyptians appear to have been the first to develop a solar calendar, using as a fixed point the annual sunrise reappearance of the Dog Star—Sirius, or Sothis—in the eastern sky, which coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile River. They built a calendar with 365 days, divided into 12 months of 30 days each, with 5 extra days at the end of the year. However, they didn't include the extra bit of time in each year, and this caused their calendar to slowly become inaccurate.

Lunar

Main article: Lunar calendarNot all calendars use the solar year as a unit. A lunar calendar is one in which days are numbered within each lunar phase cycle. Because the length of the lunar month is not an even fraction of the length of the tropical year, a purely lunar calendar quickly drifts against the seasons, which do not vary much near the equator. It does, however, stay constant with respect to other phenomena, notably tides. An example is the Islamic calendar. Alexander Marshack, in a controversial reading, believed that marks on a bone baton (c. 25,000 BC) represented a lunar calendar. Other marked bones may also represent lunar calendars. Similarly, Michael Rappenglueck believes that marks on a 15,000-year-old cave painting represent a lunar calendar.

Lunisolar

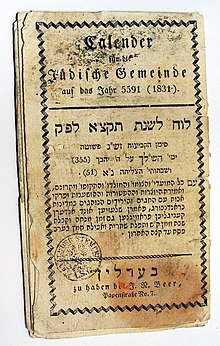

A lunisolar calendar is a lunar calendar that compensates by adding an extra month as needed to realign the months with the seasons. Prominent examples of lunisolar calendar are Hindu calendar and Buddhist calendar that are popular in South Asia and Southeast Asia. Another example is the Hebrew calendar, which uses a 19-year cycle.

Subdivisions

See also: Decade, Century, and Millennium

Nearly all calendar systems group consecutive days into "months" and also into "years". In a solar calendar a year approximates Earth's tropical year (that is, the time it takes for a complete cycle of seasons), traditionally used to facilitate the planning of agricultural activities. In a lunar calendar, the month approximates the cycle of the moon phase. Consecutive days may be grouped into other periods such as the week.

Because the number of days in the tropical year is not a whole number, a solar calendar must have a different number of days in different years. This may be handled, for example, by adding an extra day in leap years. The same applies to months in a lunar calendar and also the number of months in a year in a lunisolar calendar. This is generally known as intercalation. Even if a calendar is solar, but not lunar, the year cannot be divided entirely into months that never vary in length.

Cultures may define other units of time, such as the week, for the purpose of scheduling regular activities that do not easily coincide with months or years. Many cultures use different baselines for their calendars' starting years. Historically, several countries have based their calendars on regnal years, a calendar based on the reign of their current sovereign. For example, the year 2006 in Japan is year 18 Heisei, with Heisei being the era name of Emperor Akihito.

Other types

Arithmetical and astronomical

An astronomical calendar is based on ongoing observation; examples are the religious Islamic calendar and the old religious Jewish calendar in the time of the Second Temple. Such a calendar is also referred to as an observation-based calendar. The advantage of such a calendar is that it is perfectly and perpetually accurate. The disadvantage is that working out when a particular date would occur is difficult.

An arithmetic calendar is one that is based on a strict set of rules; an example is the current Jewish calendar. Such a calendar is also referred to as a rule-based calendar. The advantage of such a calendar is the ease of calculating when a particular date occurs. The disadvantage is imperfect accuracy. Furthermore, even if the calendar is very accurate, its accuracy diminishes slowly over time, owing to changes in Earth's rotation. This limits the lifetime of an accurate arithmetic calendar to a few thousand years. After then, the rules would need to be modified from observations made since the invention of the calendar.

Other variants

The early Roman calendar, created during the reign of Romulus, lumped the 61 days of the winter period them together as simply "winter." Over time, this period became January and February; through further changes over time (including the creation of the Julian calendar) this calendar became the modern Gregorian calendar, introduced in the 1570s.

Usage

The primary practical use of a calendar is to identify days: to be informed about or to agree on a future event and to record an event that has happened. Days may be significant for agricultural, civil, religious, or social reasons. For example, a calendar provides a way to determine when to start planting or harvesting, which days are religious or civil holidays, which days mark the beginning and end of business accounting periods, and which days have legal significance, such as the day taxes are due or a contract expires. Also, a calendar may, by identifying a day, provide other useful information about the day such as its season.

Calendars are also used as part of a complete timekeeping system: date and time of day together specify a moment in time. In the modern world, timekeepers can show time, date, and weekday. Some may also show the lunar phase.

Gregorian

The Gregorian calendar is the de facto international standard and is used almost everywhere in the world for civil purposes. The widely-used solar aspect is a cycle of leap days in a 400-year cycle designed to keep the duration of the year aligned with the solar year. There is a lunar aspect which approximates the position of the moon during the year, and is used in the calculation of the date of Easter. Each Gregorian year has either 365 or 366 days (the leap day being inserted as 29 February), amounting to an average Gregorian year of 365.2425 days (compared to a solar year of 365.2422 days).

The calendar was introduced in 1582 as a refinement to the Julian calendar, which had been in use throughout the European Middle Ages, amounting to a 0.002% correction in the length of the year. During the Early Modern period, its adoption was mostly limited to Roman Catholic nations, but by the 19th century it had become widely adopted for the sake of convenience in international trade. The last European country to adopt it was Greece, in 1923.

The calendar epoch used by the Gregorian calendar is inherited from the medieval convention established by Dionysius Exiguus and associated with the Julian calendar. The year number is variously given as AD (for Anno Domini) or CE (for Common Era or Christian Era).

Religious

The most important use of pre-modern calendars is keeping track of the liturgical year and the observation of religious feast days.

While the Gregorian calendar is itself historically motivated to the calculation of the Easter date, it is now in worldwide secular use as the de facto standard. Alongside the use of the Gregorian calendar for secular matters, there remain several calendars in use for religious purposes.

Western Christian liturgical calendars are based on the cycle of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church and generally include the liturgical seasons of Advent, Christmas, Ordinary Time (Time after Epiphany), Lent, Easter, and Ordinary Time (Time after Pentecost). Some Christian calendars do not include Ordinary Time and every day falls into a denominated season.

Eastern Christians, including the Orthodox Church, use the Julian calendar.

The Islamic calendar or Hijri calendar is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 lunar months in a year of 354 or 355 days. It is used to date events in most of the Muslim countries (concurrently with the Gregorian calendar) and used by Muslims everywhere to determine the proper day on which to celebrate Islamic holy days and festivals. Its epoch is the Hijra (corresponding to AD 622). With an annual drift of 11 or 12 days, the seasonal relation is repeated approximately every 33 Islamic years.

Various Hindu calendars remain in use in the Indian subcontinent, including the Nepali calendars, Bengali calendar, Malayalam calendar, Tamil calendar, Vikrama Samvat used in Northern India, and Shalivahana calendar in the Deccan states.

The Buddhist calendar and the traditional lunisolar calendars of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand are also based on an older version of the Hindu calendar.

Most of the Hindu calendars are inherited from a system first enunciated in Vedanga Jyotisha of Lagadha, standardized in the Sūrya Siddhānta and subsequently reformed by astronomers such as Āryabhaṭa (AD 499), Varāhamihira (6th century) and Bhāskara II (12th century).

The Hebrew calendar is used by Jews worldwide for religious and cultural affairs, also influences civil matters in Israel (such as national holidays) and can be used business dealings (such as for the dating of cheques).

Followers of the Baháʼí Faith use the Baháʼí calendar. The Baháʼí Calendar, also known as the Badi Calendar was first established by the Bab in the Kitab-i-Asma. The Baháʼí Calendar is also purely a solar calendar and comprises 19 months each having nineteen days.

National

The Chinese, Hebrew, Hindu, and Julian calendars are widely used for religious and social purposes.

The Iranian (Persian) calendar is used in Iran and some parts of Afghanistan. The Assyrian calendar is in use by the members of the Assyrian community in the Middle East (mainly Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Iran) and the diaspora. The first year of the calendar is exactly 4750 years prior to the start of the Gregorian calendar. The Ethiopian calendar or Ethiopic calendar is the principal calendar used in Ethiopia and Eritrea, with the Oromo calendar also in use in some areas. In neighboring Somalia, the Somali calendar co-exists alongside the Gregorian and Islamic calendars. In Thailand, where the Thai solar calendar is used, the months and days have adopted the western standard, although the years are still based on the traditional Buddhist calendar.

Fiscal

Main article: Fiscal calendar

A fiscal calendar generally means the accounting year of a government or a business. It is used for budgeting, keeping accounts, and taxation. It is a set of 12 months that may start at any date in a year. The US government's fiscal year starts on 1 October and ends on 30 September. The government of India's fiscal year starts on 1 April and ends on 31 March. Small traditional businesses in India start the fiscal year on Diwali festival and end the day before the next year's Diwali festival.

In accounting (and particularly accounting software), a fiscal calendar (such as a 4/4/5 calendar) fixes each month at a specific number of weeks to facilitate comparisons from month to month and year to year. January always has exactly 4 weeks (Sunday through Saturday), February has 4 weeks, March has 5 weeks, etc. Note that this calendar will normally need to add a 53rd week to every 5th or 6th year, which might be added to December or might not be, depending on how the organization uses those dates. There exists an international standard way to do this (the ISO week). The ISO week starts on a Monday and ends on a Sunday. Week 1 is always the week that contains 4 January in the Gregorian calendar.

Formats

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The term calendar applies not only to a given scheme of timekeeping but also to a specific record or device displaying such a scheme, for example, an appointment book in the form of a pocket calendar (or personal organizer), desktop calendar, a wall calendar, etc.

In a paper calendar, one or two sheets can show a single day, a week, a month, or a year. If a sheet is for a single day, it easily shows the date and the weekday. If a sheet is for multiple days it shows a conversion table to convert from weekday to date and back. With a special pointing device, or by crossing out past days, it may indicate the current date and weekday. This is the most common usage of the word.

In the US Sunday is considered the first day of the week and so appears on the far left and Saturday the last day of the week appearing on the far right. In Britain, the weekend may appear at the end of the week so the first day is Monday and the last day is Sunday. The US calendar display is also used in Britain.

It is common to display the Gregorian calendar in separate monthly grids of seven columns (from Monday to Sunday, or Sunday to Saturday depending on which day is considered to start the week – this varies according to country) and five to six rows (or rarely, four rows when the month of February contains 28 days in common years beginning on the first day of the week), with the day of the month numbered in each cell, beginning with 1. The sixth row is sometimes eliminated by marking 23/30 and 24/31 together as necessary.

When working with weeks rather than months, a continuous format is sometimes more convenient, where no blank cells are inserted to ensure that the first day of a new month begins on a fresh row.

Software

Main article: Calendaring software Further information: Category:Calendaring standardsCalendaring software provides users with an electronic version of a calendar, and may additionally provide an appointment book, address book, or contact list. Calendaring is a standard feature of many PDAs, EDAs, and smartphones. The software may be a local package designed for individual use (e.g., Lightning extension for Mozilla Thunderbird, Microsoft Outlook without Exchange Server, or Windows Calendar) or maybe a networked package that allows for the sharing of information between users (e.g., Mozilla Sunbird, Windows Live Calendar, Google Calendar, or Microsoft Outlook with Exchange Server).

See also

- General Roman Calendar

- List of calendars

- Advent calendar

- Calendar reform

- Calendrical calculation

- Docket (court)

- History of calendars

- Horology

- List of international common standards

- List of unofficial observances by date

- Real-time clock (RTC), which underlies the Calendar software on modern computers.

- Unit of time

References

Citations

- "Calendars and their History". eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- Guo, Rongxing (2018-05-16). Human-Earth System Dynamics: Implications to Civilizations. Springer. p. 159. ISBN 978-981-13-0547-4.

- Bond, Thomas; Hughes, Chris (2013-12-03). Singapore PSLE Mathematics Challenging Practice Solutions (Yellowreef). Yellowreef Limited. ISBN 978-0-7978-0222-3.

- "Do menstrual and lunar cycles synchronize? What scientists say". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 2021-02-12. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- "Introduction to Calendars". aa.usno.navy.mil. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- "History – Ancient Egyptian Calendar" (PDF). Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- Ma'Atnefert, Mwt Seshatms Nkatraet (2011). You are Harmony ... Take Time to Harmonize ... Calendars and Time Connecting. Lulu.com. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-257-10758-2.

- Lewis, James R. (2003-03-01). The Astrology Book: The Encyclopedia of Heavenly Influences. Visible Ink Press. p. 459. ISBN 978-1-57859-246-3.

- New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Sayeed, Ahmed (2019-08-10). You Must Win: The winner can create History. Prowess Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5457-4730-8.

- "Religion in the Etruscan Period" in Roman Religion Archived 15 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Shirley, Lawrence (11 February 2009). "The Mayan and Other Ancient Calendars". Convergence. Washington, DC. doi:10.4169/loci003264. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- Plofker, Kim (2009). Mathematics in India. Princeton University Press. pp. 10, 35–36, 67. ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6.

- Andersen, Johannes (31 January 1999). Highlights of Astronomy, Volume 11B: As Presented at the XXIIIrd General Assembly of the IAU, 1997. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 719. ISBN 978-0-7923-5556-4. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. Scribner. 1995. ISBN 978-0-684-19279-6.

- "Egyptians celebrate new Egyptian year on September 11". EgyptToday. 2021-09-12. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- Sayeed, Ahmed (2019-08-10). You Must Win: The winner can create History. Prowess Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5457-4730-8.

- "Calendar - The Early Roman Calendar". Encyclopedia Britannica. 24 December 2020. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "The History of the Calendar". Archived from the original on 2020-12-02.

- Onlineverdan. APTITUDE & REASONING for GATE & ESE 2020. Infinity Educations. pp. 10–6. ISBN 978-81-940294-3-4.

- Jain, Hemant (2019-01-21). RRB Junior Engineer (2019) - MATHEMATICS for 1st STAGE CBT. Infinity Educations. pp. 8–5. ISBN 978-81-939356-9-9.

- Jain, Hemant (2019-01-21). RRB Junior Engineer (2019) - MATHEMATICS for 1st STAGE CBT. Infinity Educations. pp. 8–5. ISBN 978-81-939356-9-9.

- Jain, Hemant (2019-01-21). RRB Junior Engineer (2019) - MATHEMATICS for 1st STAGE CBT. Infinity Educations. pp. 8–6. ISBN 978-81-939356-9-9.

- Zerubavel 1985.

- "Introduction to Calendars". aa.usno.navy.mil. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- The Jurist. S. Sweet. 1861. p. 983.

- Oxossi, Diego de (2022-07-08). Sacred Leaves: A Magical Guide to Orisha Herbal Witchcraft. Llewellyn Worldwide. ISBN 978-0-7387-6721-5.

- "Solar calendar | Ancient Egypt, Mayan, Aztec | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1991. p. 941. ISBN 978-0-85229-529-8.

- Lawson, Russell M. (2021-09-23). Science in the Ancient World: From Antiquity through the Middle Ages. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 979-8-216-14241-6.

- Muntz, Charles (2017-01-02). Diodorus Siculus and the World of the Late Roman Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-064901-2.

- "Solar calendar | chronology | Britannica".

- James Elkins, Our beautiful, dry, and distant texts (1998) 63ff.

- "Oldest lunar calendar identified". BBC News. 16 October 2000. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Jones, Derek (2018-03-08). "Roman Calendar". editions.covecollective.org. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- "Who Decided January 1st Is the New Year?". TIME. 2023-12-29. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- Kelechava, Brad (2016-02-11). "History of the Standard Gregorian Calendar". The ANSI Blog. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ Blackburn & Holford-Strevens 2003, pp. 682–683.

- Blackburn & Holford-Strevens 2003, pp. 817–820.

- Dershowitz & Reingold 2008, pp. 47, 187.

- Blackburn & Holford-Strevens 2003, pp. 682–689.

- Blackburn & Holford-Strevens 2003, Chapter: "Christian Chronology".

- "About the Hebrew Calendar | Yale University Library". web.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

Sources

- "calendar", American Heritage Dictionary (5th ed.), 2017

- Birashk, Ahmad (1993), A Comparative Calendar of the Iranian, Muslim Lunar, and Christian Eras for Three Thousand Years, Mazda Publishers, ISBN 978-0-939214-95-2

- Björnsson, Árni (1995) , High Days and Holidays in Iceland, Reykjavík: Mál og menning, ISBN 978-9979-3-0802-7, OCLC 186511596

- Blackburn, Bonnie; Holford-Strevens, Leofranc (2003) , The Oxford Companion to the Year (corrected reprinting of 1st ed.), Oxford University Press

- Dershowitz, Nachum; Reingold, Edward M (2008), Calendrical Calculations, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-70238-6

- Doggett, L.E. (1992), "Calendars", in Seidelmann, P. Kenneth (ed.), Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac, University Science Books, ISBN 978-0-935702-68-2

- Richards, E.G. (1998), Mapping Time, the calendar and its history, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-850413-9

- Rose, Lynn E. (1999), Sun, Moon, and Sothis, Kronos Press, ISBN 978-0-917994-15-9

- Schuh, Dieter (1973), Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der Tibetischen Kalenderrechnung (in German), Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, OCLC 1150484

- Spier, Arthur (1986), The Comprehensive Hebrew Calendar, Feldheim Publishers, ISBN 978-0-87306-398-2

- Zerubavel, Eviatar (1985), The Seven Day Circle: The History and Meaning of the Week, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-98165-9

Further reading

- Fraser, Julius Thomas (1987), Time, the Familiar Stranger (illustrated ed.), Amherst: Univ of Massachusetts Press, Bibcode:1988tfs..book.....F, ISBN 978-0-87023-576-4, OCLC 15790499

- Whitrow, Gerald James (2003), What is Time?, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-860781-6, OCLC 265440481

- C.K, Raju (2003), The Eleven Pictures of Time, SAGE Publications Pvt. Ltd, ISBN 978-0-7619-9624-8

- C.K, Raju (1994), Time: Towards a Consistent Theory, Springer, ISBN 978-0-7923-3103-2

External links

- "Calendar" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. IV (9th ed.). 1878. pp. 664–682.

- "Calendar" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 987-1004.

- "Calendar" . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Calendar converter, including all major civil, religious and technical calendars.

| Calendars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systems | |||||||

| In wide use | |||||||

| In more limited use |

| ||||||

| Historical | |||||||

| By specialty |

| ||||||

| Reform proposals | |||||||

| Displays and applications | |||||||

| Year naming and numbering |

| ||||||

| Fictional | |||||||

| Time | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key concepts | |||||||||

| Measurement and standards |

| ||||||||

| Philosophy of time | |||||||||

| Human experience and use of time | |||||||||

| Time in science |

| ||||||||

| Related | |||||||||

| Time measurement and standards | ||

|---|---|---|

| International standards |

|   |

| Obsolete standards | ||

| Time in physics | ||

| Horology | ||

| Calendar | ||

| Archaeology and geology | ||

| Astronomical chronology | ||

| Other units of time | ||

| Related topics | ||

| Chronology | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key topics | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Calendars |

| ||||||||

| Astronomic time | |||||||||

| Geologic time |

| ||||||||

| Chronological dating |

| ||||||||

| Genetic methods | |||||||||

| Linguistic methods | |||||||||

| Related topics | |||||||||