This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Russianname (talk | contribs) at 12:36, 22 June 2007. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:36, 22 June 2007 by Russianname (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Battle of Konotop | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Ukrainian civil war - The Ruin 1657-1687 | |||||||

| Polish Hussar Petro Andrusiv. Hetman Vyhosky routes the tsar's army near Konotop. 1659 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Ukrainian Cossacks and their allies | Russian Tsardom | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ivan Vyhovsky | Aleksey Trubetskoy | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 60,000 | between 100,000 and 150,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4,000 Cossacks, 6,000 Tatars | 30,000 | ||||||

The Battle of Konotop (also known as Battle of Sosnivka) was a battle fought between the hetman of Ukraine Ivan Vyhovsky and his allies, and the armies of Russian Tsardom, led by prince Aleksey Trubetskoy, on June 29 1659 near the town of Konotop (now Sumska Oblast, Ukraine).

Prelude

This war happened during the period of Ukrainian history that is generally referred to as the Ruin. It was a time of incessant internal strife and intermittent civil war between different factions within the Ukrainian Cossack elite that were vying for power. This period started with the death of charismatic and a very influential hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky in 1657.

During his reign, Bohdan Khmelnytsky managed to wrestle Ukraine out from Polish domination, but was forced to enter into new and uneasy relation with Russian Tsardom in 1654. His successor, general chancellor and close adviser Ivan Vyhovsky, was left to deal with Moscow's growing interference in Ukraine's internal affairs and even overt instigation of a civil war by way of supporting Cossack factions opposing Vyhovsky. With the situation deteriorating rapidly and opposition to his rule mounting, Vyhovsky entered into negotiations with his former foes, the Poles, and finally concluded a Treaty of Hadiach on September 16 1658. Under the new treaty Ukraine was to become an equal constituent nation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth along with Poland and Lithuania under a name of Principality of Rus, forming the Polish-Lithuanian-Ruthenian Commonwealth.

This news alarmed the Ukrainian cossacks and Moscow to the extent that an expeditionary force was dispatched to Ukraine in the autumn of 1658 headed by Prince Grigory Romodanovsky. Moscow's military commander not only supported the election by Vyhovsky's opponents of a new rival hetman, but started actively to occupy towns held by Vyhovsky's supporters. The latter were mercilessly exterminated along with wide-spread abuse and robbery of the civilian population.

The situation having escalated that far, open hostilities followed. Skirmishes and attacks occurred in different towns and regions throughout the country, the most prominent of which was the capture of Konotop by Cossacks of the Nizhyn and Chernihiv Regiments headed by Hryhoriy Hulyanytsky, a colonel of Nizhyn. In the spring of 1659 a huge army — estimated to be 150,000 men strong — was dispatched to Ukraine to assist Romodanovsky. The army came to the Ukrainian border on January, 30, 1659 and stood 40 days till Trubetskoy negotiated with Vyhovsky since the Russian commander had instruction to persuade cossacks. Vyhovsky's rival Cossack forces of commanders Bezpaly, Voronko and Zaporizhian Cossacks of Barabash joined the Russian troops. The supreme military commander Prince Aleksey Trubetskoy decided to finish off the small 4,000 garrison of the Konotop castle held by Cossacks of Hulyanytsky before proceeding in his pursuit of Vyhovsky.

Siege of Konotop

Prince Trubetskoy's hopes for quick resolution of the Konotop stand-off were dimmed when Hulyanytsky and his Cossacks refused point blank to betray hetman Vyhovsky and mounted fierce and protracted defence of Konotop. On April 21 1659, after a morning prayer, Trubetskoy ordered an all-out assault on the fortress's fortifications. The city was shelled, a few incendiary bombs were dropped inside, and the huge army moved on to capture the city. At one point the troops of Trubetskoy even broke inside the city walls, but were thrown back by the fierce resistance of the Cossacks inside. After the fiasco of the initial assault, Trubetskoy abandoned his plans of a quick assault and proceeded to shell the city and to fill the moat with earth. The Cossacks stubbornly held on in spite of all the fire unleashed on the city: during the night the earth put to fill in the moat was used to strengthen the city walls, and the besieged even undertook several daring counterattacks on Trubetskoy's besieging army. These attacks forced Prince Trubetskoy to move his military camp 10 km away from the city and thereby split his forces between the main army at his HQ and the army besieging Konotop. It is estimated that in the siege alone the Trubetskoy forces suffered casualties up to 10,000 men. Instead of a quick campaign the siege dragged on for 70 days and gave Vyhovsky the much-needed time to prepare for the battle with the Russian army.

The hetman not only managed to organize his own troops, but secured support of his allies — the Crimean Tatars and the Poles. By agreement with the Tatars, the Khan Mehmed IV Giray, at the head of his 30,000-strong army, made his way towards Konotop in early summer of 1659, as did the 4000-man Polish detachment with the support of Serbian, Moldavian and German mercenaries.

Battle

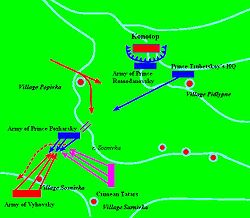

By June 24 1659 Vyhovsky and his allies approached the area and defeated a small reconnaissance detachment of the invader's army near the village of Shapovalivka , several kilometers south-west of Konotop. According to the plan made that evening, the 30,000 Tatars were left in an ambush south-east of the river Sosnivka, and Vyhovsky's forces with Poles and mercenaries were positioned at the village of Sosnivka, south of the river with the same name

Meanwhile, Vyhovsky left the command of his forces to the brother of Hryhoriy Hulyanytsky, Stepan Hulyanytsky, and at the head of a small Cossack detachment left for Konotop . Early morning of June 27 1659, Vyhovsky's detachment attacked Trubetskoy's army near Konotop, and using this sudden and unexpected attack managed to capture a sizable number of the enemy's horses and drive them away and further into the steppe . The enemy counterattacked, and Vyhovsky retreated across the bridge to the other bank of the Sosnivka river in the direction of his camp . Having learned of the assault, Prince Trubetskoy dispatched a large detachment of 30,000 men, led by Prince Semen Pozharsky and Cossacks of appointed rival hetman Bezpalyi, across the river to pursue Ivan Vyhovsky. Trubetskoy's forces were thus divided between this detachment, those besieging Konotop and the 30,000 at his HQ .

On June 28 1659 Prince Semen Pozharsky, in his pursuit of the Cossacks, crossed the river Sosnivka and made his camp on the southern bank of the river. During the night a small Cossack detachment led by Stepan Hulyanytsky, having padded the hoofs of their horses with cloth, stole under the cover of night behind the enemy lines and captured the bridge that Pozharsky used to cross the river. The bridge was dismantled and the river dammed, thus flooding the valley around it.

Early on the morning of June 29 1659, Vyhovsky at the head of a small detachment attacked Prince Pozharsky's army. After a little skirmish with a far larger army than his, he started to retreat, feigning a disorganized flight in the direction of his main forces. Unsuspecting Pozharsky ordered his army to pursue the enemy. Once the enemy's army entered Sosnivka, the Cossacks fired three cannon shots to give the signal to the Tatars and counterattacked with all the forces stationed at Sosnivka. Having discovered the trap, Prince Semen Pozharsky ordered retreat; but his heavy cavalry and the artillery got bogged down in the soggy ground created from the flooding the night before. At this moment the Tatars also advanced from the eastern flank, and the outright slaughter ensued. Almost all 30,000 troops perished, with few of them captured alive. Among the captured were Prince Semen Romanovich Pozharsky himself, Prince Semen Petrovich Lvov, both Princes Buturlins, Prince Lyapunov, Prince Skuratov, Prince Kurakin and others. A relative of the Great Liberator of Moscow from the Poles, Dmitry Pozharsky, Prince Semen Romanovich Pozharsky was brought before the Khan of Crimea Mehmed IV Giray. Pozharsky made bold with the Khan (according to the Witness who gave the only written source about the events) or even hurled obscenities and spat in his face (according to Sergey Solovyov, ). For that he was promptly beheaded by the Tatars, and his severed head was dispatched with one of the captives to Prince Trubetskoy's camp.

Having learned about the defeat of Pozharsky's army, Trubetskoy ordered the siege of Konotop lifted and started his retreat from Ukraine. At that moment the Cossacks of Hulyanytsky inside the fortress emerged from behind the walls and attacked the retreating army. Trubetskoy lost, in addition, most of his artillery, his military banners and the treasury. The retreating army defended well and Vyhovsky and the Tatars abandoned their 3-day long pursuit near the Russian border.

Aftermath and significance

As Trubetskoy's troops arrived in Putivl, the the news of the battle reached Moscow as well.

However, the Russian tsar did not have to worry; the Ukrainian civil war of the Ruin period accomplished what Trubetskoy and his troops could not. Had only hetman Vyhovsky and his allies been able to capture a few of Ukrainian towns held by his opponents, when the first bad news arrived: Cossacks of the Zaporozhian Host led by Ivan Sirko attacked Crimean outposts in the south, and Khan Giray was forced to leave him for his country. The authority of Vyhovsky was low after the bloody battle against the Russians. A few cities rebelled against him immediately: Lokhvytsia, Hadyach, Poltava, Romny . It was only 2 months after the battle when the citizens of Nizhyn gave a ceremonial welcome to Trubetskoy and swear an oath of allegiance to the Russian tsar. The same month the Ukrainian citizens and cossacks regiments in Kiev, Pereyaslav, Chernihiv swore an oath to the tsar as well . In September the cossacks on their counsil hacked to death both Ukrainian delegates who signed the Hadyach treaty and thus started the war with Russia.

Thus Vyhovsky was left to deal with the growing opposition to his rule. By the end of the year he was forced to resign and to flee to Poland where he was later executed by the Poles in 1664. His defeat is largely attributed to his alliance with the very unpopular Poles and his inability to seek support among all the strata of the Ukrainian population and not just among the rich Cossack elite, who were willing to betray him at every opportunity either to Moscow or Warsaw. The civil war raged on and the victors of the Konotop battle were soon forgotten.

Together with a number of other battles between East Slavs, such as Battle of Orsha, the Konotop battle was with a few exceptions an abandoned topic in Russian Imperial and in Soviet historiography . This attitude towards this event is explained by the fact that it dispelled some Russian propaganda positions about the unity of East Slavs , in particular the ones about "eternal friendship of Russian and Ukrainian peoples" and about "natural desire of Ukrainians for union with Russia". For all the skill and the bravery of the Cossacks — especially those defending Konotop — it still remains a bitter victory. A victory that did not have any significant impact on the course of Ukrainian history, where fratricidal war of the Ruin and personal ambitions of treacherous hetmans prevailed . As such, the Konotop battle remains a classic example of the battle won and a war lost.

Sources

- Orest Subtelny. Ukraine. A history. University of Toronto press. 1994. ISBN 0-8020-0591-0.

- David Mackenzie, Michael W. Curran. A History of Russia, the Soviet Union, and Beyond. Fourth Edition. Belmont, California. p. 200, 1993. ISBN 0-534-17970-3.

- Yuri Mytsyk. Battle of Konotop 1659

- Sokolov C. M. Continuation of reign of Alexi Mikhailovich. Chapter 1.

- Makhun S. Battle of Konotop. Reittarr. No. 23.

References

- ^ The Reign of Tsar Alexi Mikhailovich. (Solovyov S. М.)

- The number of Russian troops varies in different sources. "The cronicle of the Witness" puts the number of Russian troops at 100,000 men, while the famous Russian historian Sergei Solovyov gives the number at 150,000 or more Chronicle of the Witness

- History of Little Russia (N. Маrkevich).

- ^ The Konotop battle of 1659..

- Yuriy Mitsyk. Ivan Vyhovsky.

- ^ A. G. Bulvinsky. History of Ukrainian military and military art.

- ^ Дорошенко Д. Нарис історії України. Львів: Світ, 1991, с 294

- Каргалов В.В. Русские воеводы 16-17 веков. М.:Вече, 2005. - с.280.

- The Konotop battle as an example of Ukrainian military skill.

- Yuriy Mitsyk. The Glory of Konotop.

- The Konotop Battle. S. Makhun.

External links

- The Reign of Tsar Alexi Mikhailovich. (Solovyov S. М.) (Rus.)

- History of Konotop (Ukr.)

- Historical Encyclopedia (Ukr.)

- The Konotop Tragedy. 1659. (Rus.)

- The Battle of Konotop (Rus.)

- History of Little Russia (N. Маrkevich) (Rus.)

- The Konotop Battle. S. Makhun. (Rus.)

- The Konotop battle as an example of Ukrainian Cossack military skill (Ukr.)