This is an old revision of this page, as edited by ForeignerFromTheEast (talk | contribs) at 00:02, 30 October 2007 (→Identities: reinsert passage, corr). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:02, 30 October 2007 by ForeignerFromTheEast (talk | contribs) (→Identities: reinsert passage, corr)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)This article is about the Slavic ethnic group; for the unrelated people of ancient and modern Greece, see Ancient Macedonians and Macedonians (Greek) respectively. For other meanings, see Macedonian. Ethnic group

| File:Maceds2.jpgRisto Krle · Blaže Koneski · Simon Trpčeski · Metodija Andonov - Čento | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 1.7 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1, 297, 981 | |

| 962 (official census) - c.200,000 (Britannica estimate) | |

| 83, 978 | |

| 61, 105 | |

| 58, 460 | |

| 42, 812 | |

| 31, 265 | |

| 25, 847 | |

| 6, 415 | |

| 5, 145 | |

| 5, 071 | |

| 4, 697 | |

| 4, 270 | |

| 3, 972 | |

| 2, 300 | |

| 2, 278 | |

| 731 | |

| Elsewhere | unknown |

| Languages | |

| Macedonian | |

| Religion | |

| predominantly Macedonian Orthodox, Muslim, Protestant, Eastern Orthodox and others | |

The Macedonians (Template:Lang-mk, Тransliteration: Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))– also referred to as Macedonian Slavs– are a South Slavic ethnic group who are primarily associated with the Republic of Macedonia. They speak the Macedonian language, a South Slavic language. About three quarters of all ethnic Macedonians live in the Republic of Macedonia, although there are also communities in a number of other countries.

Population

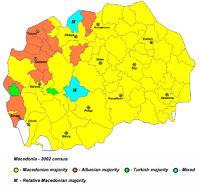

The vast majority of Macedonians live along the valley of the river Vardar, the central region of the Republic of Macedonia and form about 64.18% of the population of the Republic of Macedonia (1,297,981 people according to the 2002 census). Smaller numbers live in eastern Albania, southwestern Bulgaria, northern Greece, and southern Serbia, mostly abutting the border areas of the Republic of Macedonia. A large number of Macedonians have immigrated overseas to Australia, USA, Canada and in many European countries: Germany, UK, Italy, Austria, etc.

Macedonians abroad

Serbia

Serbia recognizes the Macedonian minority on its territory as a distinct ethnic group and counts them in its annual census. 25,847 people declared themselves Macedonians in the 2002 census.

Bulgaria

In the 2001 census in Bulgaria, 5,071 people declared themselves etnnic Macedonians (see the official data in Bulgarian here). Krassimir Kanev, chairman of the NGO Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, claimed 15,000 - 25,000 in 1998 (see here). In the same report Macedonian nationalists (Popov et al, 1989) claimed that 200,000 etnic Macedonians live in Bulgaria. However, Bulgarian Helsinki Committee stated that the vast majority of the Slavic population in Pirin Macedonia has a Bulgarian national self-consciousness and a regional Macedonian identity similar to the Macedonian regional identity in Greek Macedonia (see here). Finally, according to personal evaluation of a leading local ethnic Macedonian political activist, Stoyko Stoykov, the present number of Bulgarian citizens with ethnic Macedonian self-consciousness is between 5,000 and 10,000 (source). (The Encarta Encyclopedia states that Macedonians make up 2.5% of the total population, i.e. approximately 190,000, with no mention of how this figure is obtained, as it is evidently refuted by the latest census figures, see here.)

Macedonian groups in the country have reported official harassment (see Human rights in Bulgaria), with the Bulgarian Constitutional Court banning a small Macedonian political party in 2000 as separatist and Bulgarian local authorities banning political rallies. A political organization of the Macedonian minority in Bulgaria – UMO Ilinden-Pirin – claims that the minority has experienced a period of intensive assimilation and repression. It should be noted though that the Republic of Macedonia banned a similar pro-Bulgarian organization - Radko - as separatist.

Albania

Albania recognizes ethnic Macedonians as an ethnic minority and delivers primary education in the Macedonian language in the border regions where most ethnic Macedonians live. In the 1989 census, 4,697 people declared themselves ethnic Macedonians.

Ethnic Macedonian organizations allege that the government undercounts their number and that they are politically underrepresented - there are no ethnic Macedonians in the Albanian parliament. Some say that there has been disagreement among the Slav-speaking Albanian citizens about their being members of a Macedonian nation as a significant percentage of their number are Torbeshes and self-identify as Albanians. External estimates on the population of ethnic Macedonians in Albania include 10,000 , whereas ethnic Macedonian sources have claimed that there are 120,000 - 350,000 ethnic Macedonians in Albania .

Greece

Claims regarding the existence of an ethnic Macedonian minority in Greece are rejected by the Greek government. These claims are directed at the Slavic-speaking community of northern Greece, which dominantly self-identifies as Greek (not as ethnic Macedonian) and defines its language as Slavic or Dopia (a Greek word for 'local'). This community numbered by 41,017 people according to the latest Greek census to include a question on mother tongue held in 1951, and local authorities in Greece continue to acknowledge its existence. Depending on dialect, this language is classified by linguists as either Bulgarian or Macedonian. The size of this community today is estimated at between 100,000 and 200,000 by the Greek Helsinki Monitor, however, it also states that only an estimated 10,000-30,000 of these people might have an ethnic Macedonian national identity, basing this figure on the electoral performance of the only political party in Greece promoting the recognition and existence of an ethnic Macedonian minority in Greek Macedonia: the Rainbow, which was founded around 1995 and received only 2,955 votes in Greek Macedonia in the 2004 elections . In 2007, it did not stand for elections. The rest of the Slavic-speakers of northern Greece who don't self-identify as ethnic Macedonians, but as Greeks are often pejoratively referred to as Grkomani by some people in the Republic of Macedonia and transnational ethnic Macedonian communities. In 1993, at the height of the name controversy and just before joining the UN, the government in Skopje claimed that there were between 230,000 and 270,000 Macedonians living in northern Greece, while the Athens government claimed there were around 100,000 Greeks in the Republic of Macedonia..

According to an unofficial survey by Encyclopedia Britannica 2007, Macedonians make up 1.8% of the total population of Greece (about 200,000) .

Other countries

Significant Macedonian communities can also be found in the traditional immigrant-receiving nations, as well as in Western European countries. It should be noted that census data in many European countries (such as Italy and Germany) does not take into account the ethnicity of émigrés from the Republic of Macedonia:

- Australia: The official number of Macedonians in Australia by birthplace or birthplace of parents is 82,000 (2001). The main Macedonian communities are found in Melbourne, Geelong, Sydney, Wollongong, Newcastle, Canberra and Perth. (The 2006 Australian Census included a question of 'ancestry' which, according to Members of the Australian-Macedonian Community, will result in a significant increase of 'ethnic Macedonians' in Australia) See also Macedonian Australians;

- Canada: The Canadian census in 2001 records 31,265 individuals claimed wholly- or partly-Macedonian heritage in Canada (2001), although community spokesmen have claimed that there are actually 100,000-150,000 Macedonians in Canada (see also Macedonian Canadians);

- USA: A significant Macedonian community can be found in the United States of America. The official number of Macedonians in the USA is 43,000 (2002). The Macedonian community is located mainly in Michigan, New York, Ohio, Indiana and New Jersey (See also Macedonian Americans);

- Germany: There are an estimated 61,000 citizens of the Republic of Macedonia in Germany (2001);

- Italy: There are 58,460 citizens of the Republic of Macedonia in Italy (2004).

Other significant ethnic Macedonian communities can also be found in the other Western European countries such as Austria, France, Switzerland, Netherlands, United Kingdom, etc.

History

Origins

The ancestry of present-day Macedonians is mixed. Their ethnogenesis occurred during the 6th century when various Slavic tribes migrated to, and settled in, the region of Macedonia. These tribes are reputed for their acceptance of other tribal peoples, and most ethnographers such as Vasil Kanchov, Gustav Weigand, and the anthropologist Carleton S. Coon posit that they absorbed part of the indigenous populations of the area, including Greeks, Thracians and Illyrians. . They also may have mixed with later groups such as Bulgars, as stated by the Byzantine chroniclers Theophylact Simocatta and Nicephorus. Coon, in his book The Races Of Europe, together with his predecessor William Z. Ripley, described the Slavic speakers in Macedonia as Bulgarians. Following researchers such as Bertil Lundman have been placed the both populations in a common racial subgroup, according the book The Races And Peoples Of Europe.

The Macedonian population is also of special interest for HLA anthropological study in the light of unanswered questions regarding its origin and relationship with other populations, especially the neighbouring Balkanians. A phylogenetic tree constructed on the basis of the high-resolution data deriving from other populations revealed the clustering of Macedonians together with other Balkan populations - Bulgarians, Serbians, Croats and Romanians, being most related to Bulgarians and Serbians.

Identities

Macedonians are people with a unique identity derived from an influence of different cultures. The large majority identify themselves as Orthodox Christians, who speak a Slavic language, and share similarities in culture with their Balkan neighbours. However, the concept of a distinct "Macedonian" ethnicity is seen as a relatively new arrival to the millieu of peoples that is the Balkans. Any reference to Macedonians in medieval and early modern times was used as a regional description rather than a separate ethnic designation. Such examples include the Greek Macedonian dynasty which at one stage ruled the Byzantine Empire. References have been made to Macedonian Slav rebellions against Byzantine rule , but these have been interpreted by most scholars as non-specific, regional designations. The first ethnographic data pertaining to the Macedonian region as a whole emerged during Ottoman rule. These censi lacked any reference attesting to a specific Macedonian identity, but only records the population as either Greek or Bulgarian, as well as other minorities - Turks, Aromanians, Jews, Albanians.

Most of the ethnographers and travelers during Ottoman rule identified the majority of the Slavic speakers as 'Bulgarians', as for example the 17th Century traveler Evliya Celebi in his Seyahatname - Book of Travels, until the Ottoman census of Hilmi Pasha in 1904 and later. Evidence also exists that certain Macedonian Slavs, particularly those in the northern regions, considered themselves Serbs. This continued until the period between 1878 and 1912 when the rival propaganda of the new established Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria succeeded in engaging the Slavophone population of Macedonia into three distinct parties, the pro-Serbian, the pro-Greek or the pro-Bulgarian one. The “Macedonian Question,” became especially prominent after the Balkan wars in 1912-1913 and the subsequent division of Macedonia between the three neighboring states, followed by tensions between them over possession of Macedonia. This partitioning of the territory had a tremendous influence on the development of the Macedonian national identity. In order to legitimise their claims, each of these countries tried to 'persuade' the population into allegiance.. These scientists argue also that the use of any ethnic definition of the Slav speekers in Macedonia during the 19th and early 20th Century did not refer to ethnicity, but rather a socio-occupational description. The Slav population in Macedonia tended to be Christian peasents, farming folk, attested socio-political circumstances, such as in what language the local schooling was provided, or whether the local church alligned itself with Serbian, Bulgarian or Greek Orthodoxy. The majority were under the influence of the Bulgarian Exarchate and its education system, thus in the early 20th century and beyond, were regarded as Bulgarians, whatever that meant.(Brubaker 1996: 153; Ruhl 1916: 6; Perry in Lorrabee 1994: 61) After the establishment of P.R. Macedonia in 1944, the Yugoslav government began a policy of removing any Bulgarian influence and cementing a Macedonian identity. Today a mere 0.5% of the population identify as Macedonian Bulgarians.

Some scholars believe that the late development of a distinct Macedonian identity was the result of an oppressive and backward Turkish regime whose rule lasted the longest in the region of Macedonia. This was followed by tensions between Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece over possession of Macedonia. In order to legitimize their claims, each tried to 'persuade' the population into allegiance. These scientists argue also that the use of any ethnic definition of the Slav speekers in Macedonia during the 19th and early 20th Century did not refer to ethnicity, but rather a socio-occupational description. The Slav population in Macedonia tended to be Christian peasents, farming folk, attested socio-political circumstances, such as in what language the local schooling was provided, or whether the local church alligned itself with Serbian, Bulgarian or Greek Orthodoxy. The majority were under the influence of the Bulgarian Exarchate and its education system, thus in the early 20th century and beyond, were regarded as Bulgarians, whatever that meant.(Brubaker 1996: 153; Ruhl 1916: 6; Perry in Lorrabee 1994: 61)

The national awakening of the ethnic Macedonians can be said to have begun in the late 19th century and early 20th century - this is the time of the first expressions of ethnic nationalism by limited groups of intellectuals in Belgrade, Sofia, Istambul, Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg. This period marks the beginning of the process of the construction of a Macedonian national identity and culture. However the key events in the formation of a distinctive Macedonian identity emerged during the first half of the 20th century in the aftermath of the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 when the Bulgarian Exarchate discontinued its activity in most of the region. The process strengthed especially following the Second World War, with the withdrawal of Bulgarian authorities from Macedonia, the establishment of Yugoslav Macedonian Republic and the signing of Bled agreement. With the founding of the People's Republic of Macedonia in 1944 as part of SFRY, a sense of a Macedonian national identity gained strength and became systematised.(Bell 1998:193)

After the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1991 and and declaring of Independence of Republic of Macedonia the “Macedonian Question” has again intensified. The issue primarily involves the Republic of Macedonia's neighbours, Greece and Bulgaria, who have been criticised by justice organisations for denying the existence of an independent ethnic Macedonian identity and the existince of ethnic Macedonian minorities on their territories. During the last few years, rising economic prosperity in Bulgaria has seen around 50,000 Macedonians applying for Bulgarian citizenship; in order to obtain it they must sign a statement declaring they are Bulgarian by origin, effectively not recognising their rights as a minority.. All Bulgariаn governments justify this policy because they regard Macedonians as ethnopolitically disoriented Bulgarians.. Greece has raised concerns about the activities of Macedonists, who propagate the idea of a United Macedonia, i.e. bringing Greek and Bulgarian territories under the control of the Republic of Macedonia. As Basil Gounaris puts it: "Although a diplomatic solution to these issues is not impossible, a compromise is highly improbable as long as Macedonian history is analysed retrospectively in terms of rigid modern-day definitions of ethnicity."

Ancient period

The region that today forms the Republic of Macedonia has been inhabited since Paleolithic times. What is now the modern Republic of Macedonia was settled by the Paeonians and Dardani, peoples of mixed Thraco-Illyrian origin. The Paionians founded several princedoms which colalesced into a kingdom centered in the central and upper reaches of the Vardar and Struma rivers. In 360-359 AD Paionian tribes were launching raids into Macedon(Diodorus XVI. 2.5) in support of an Illyrian invasion.

Under Philip II of Macedon (359–336 BC), Macedon, situated in what is now Central Greek Macedonia, expanded into the territories of the neighbouring Paionians, Thracians, and Illyrians. Among this conquests he annexed the regions of Pelagonia and Southern Paionia, which roughly corresponds to the most southern regions of Republic of Macedonia. The kingdom of Paionia, then ruled by Agis, adequatе approximately to the most of the territory of today Republic of Macedonia was reduced to a semi-autonomous, subordinate status. Philip's son Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) managed to briefly extend Macedonian power not only over the Balkans, but also to the Persian empire, including Ancient Egypt and lands as far east as the fringes of India, heralding the Hellenistic period.

The Roman province of Macedonia was officially established in 146 BC, after the Roman general Quintus Caecilius Metellus defeated Andriscus of Macedon in 148 BC, and after the four client republics established by Rome in the region were dissolved. The province incorporated Epirus Vetus, Thessaly, and parts of Illyria and Thrace. In the 3rd century or 4th century, the province of Macedonia was divided into Macedonia Prima (in the south) and Macedonia Salutaris (in the north).

Arrival of Slavs

Main article: South SlavsThe Slavs entered the Balkan Peninsula in the 6th century AD, settling in the Danube river basin. According to Procopious, the first attack on Byzantium took place in 523.

By 581, many Slavic tribes had settled the land around Thessaloniki, though they did not capture the city itself, which was only saved, so the people of Thessalonica believed, by the help of their patron Demetrios. Archbishop John of Thessaloniki mentions an attack on the city by 5000 Slav warriors.. As John of Ephesus tells us in 581: “the accursed .. Slavs wandered across the whole of Greece, the lands of the Thessalonians and the whole of Thrace, taking many towns and forts, .. and making themselves rulers of the whole country”, creating a Macedonian Sclavinia. By 586, they took the western Peloponnese, Attica and Epirus, leaving only the east part of Peloponnese, which was mountainous and inaccessible.

Initially the Slavic tribes retained independent rule with their own political structure. These units were referred to as Sclavenes. Byzantine emperors tried to directly incorporate the Slavs of the Macedonian region into the socio-economic system of the Byzantine state, with varied success. The Thracian theme was returned to imperial rule in 680-681. However the Slavs of Greece and Macedonia proved more stubborn, and resisted Hellenization. Emperors Constans (656) and Justinian II (686) had to resort to military expeditions and forced re-settlement of large numbers of Slavs to Anatolia, forcing them to pay tribute and supply military aid to the empire. With the formation of the First Bulgarian Empire, the remaining Sclavenes were incorporated into the Bulgarian Empire, as was the entire Region of Macedonia, thus cementing the Slavic character of the area.

Despite the raiding and looting, many local populations willingly assimilated with the Slavs. Additionally, the slavs actively incorporated prisoners into their ranks . Slavicisation is a term used to describe this cultural and linguistical change in which non-Slavic peoples becomes Slavic. The term here is used in connection with the Greeks, Hellenized and Romanized Thracians, Paionians and Illyrians on the territory of Macedonia, which fell in Slavic sphere of influence after arrival of the Slavs. Thus the settlement of Macedonia by southern Slavs was not only a destructive wave of invasion. Analysis of anthropological evidence and material culture demonstrates the significant biological and cultural contribution of previous populations of these territories in the formation of what would become modern Macedonians. Remains dating back to the 6th century represent a specific mixture of Slavic, Illyrian, Thracian and Byzantine elements.

Arrival of Bulgars

Main article: Bulgars

From 493 the Bulgars carried out frequent attacks on the western territories of the Byzantine Empire. Later raids were carried out at the end of the 5th century and the beginning of the 6th century. After several centuries of Bulgar raids against Byzantium, around 680 a group of Bulgars led by Bulgarian Khan Kuber settled in the region of Keramisian plain. He was the brother of Khan Asparuh, who founded the Danubian Bulgarian state in 681, known as First Bulgarian Empire. In the following decades these Bulgars launched campaigns against the Byzantine city of Thessaloniki and established contacts with Danubian Bulgaria. By the early 9th century the lands that Kuber settled had been incorporated into the First Bulgarian Empire.

The archaeologist from Republic of Macedonia, Ivan Mikulchik, revealed the presence not only of the Kuber group, but the whole later Bulgar archaeological culture throughout Macedonia.

Christianization and adopting of Cyrillic alphabet

The historical phenomenon of Christianization, the conversion of individuals to Christianity or the conversion of entire peoples at once, also includes the practice of converting pagan practices, pagan religious imagery, pagan sites and the pagan calendar to Christian uses. After Roman Empire was declared a Christian Empire by Theodosius I in 389, laws were passed against pagan practices over the course of the following years. The Slavic tribes in Macedonia accepted the Christianity as their own religion around the 9th century mainly during the reign of prince Boris I of Bulgaria.The Christianization of Bulgaria was the process of converting 9th-century medieval Bulgaria to Christianity as state religion.

The creators of the Glagolitic alphabet were the Byzantine Greek monks Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius. Under the guidance of the Patriarchate at Constantinople they were promoters of Christianity and initiated Slavic literacy among the Slavic people. They developed their alphabet from their extensive knowledge of the local Slavic dialect spoken in the hinterland of Thessaloniki, which became the basis for Old Church Slavonic, the first literary Slavic language. Their work was accepted in early medieval Bulgaria and continued by the St. Clement of Ohrid, creator of Cyrillic alphabet and St.Naum of Ohrid as founders of the Ohrid Literary School. Cyril and Methodius evangelized from Constantinople into the Balkans In the legacy of Cyril and Methodious, carried on by Clement and Naum, the development of Slav literacy was crucial in preventing assimilation of the Slavs either by cultures to the North or by the Greek culture to the south. The introduction of Slavic liturgy paralleled Boris' continued development of churches and monasteries throughout his realm.

Middle ages

During most of Late Antiquity and the early Middles ages Macedonia (as a region) had been a province of the Byzantine Empire. In the 6th century AD, the part which today forms the Greek province of Macedonia was known as Macedonia Prima (first Macedonia), and contained the Empire's second largest city, Thessaloniki. The rest of the modern region (today's Republic of Macedonia and Western Bulgaria) was known as Macedonia Salutaris. In the early 9th century, most of the region of Macedonia (excluding the area of Thessaloniki), as well as large parts of the Balkan peninsula, were incorporated into the First Bulgarian Empire. With the defeat of the Bulgarian empire by Byzantium, in the late 10th century the eastern part of the Bulgrian empire and its capital Preslav were annexed into the Byzanine Empire. The eastern part continued to be independent, and was ruled by Tsar Samuil of Bulgaria, who saw himself as the successor of the Bulgarian Empire. Samuil ruled his kingdom from the island of St. Achilles in Prespa. He was crowned in Rome in 997 as Tsar of Bulgaria by Pope Gregory V. The remains of his castle are still present in the city of Ohrid. Under Samuil, the fortunes of the empire and the great military rivalry against Byzantium were once more revived, albeit temporarily. However, Samuil’s army was soundly defeated in 1014 by Basil II The Bulgar-Slayer, emperor of Byzantium, and four years later Bulgarian Empire fell once again under Greek control. The character of Samuil has taken mythical status in folklore of Macedonian people, seeing him as a local King who struggled against Greek hegemony.

In the 13th century the region was briefly passed to Latin, Bulgarian and back to Greek rule. For example Konstantin Asen, former nobleman from Skopje ruled over the region as Tsar of Bulgaria from 1257 to 1277. In the 14 century this area was conquered by the Serbian Empire of Tsar Stefan Dušan. However, with his death the region fell under leadership of local nobles, who divided his territories between them. Disunited, the feudal rulers fell to the end of 14 century to the emerging Ottoman Empire one by one.

Ottoman Empire, Turkification and Islamization

See also: Rumelia

This expansion of medieval states on the Balkan Peninsula was discontinued by the occupation of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th century. The region of Macedonia remained part of the Ottoman Empire for the next 500 years, i.e. until 1912. Islamization means the process of a society's conversion to the religion of Islam, or a neologism meaning an increase in observance by an already Muslim society. Turkification is a term used to describe a cultural change in which someone who is not a Turk becomes one, voluntarily or by force. Both terms can be used in contexts of connection with various Slavic people in Macedonia (Pomaks, Torbesh and Gorani), which converted to Islam during the Ottoman rule. Overall, the large majority of ethnic Macedonians remained Christian.

During the rule of the Ottomans, the locals organized a number of uprisings: Mariovo uprising (1564), Karposh's Rebellion (1689), Kresna-Razlog Uprising(1878) etc. According to the Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano between Russia and the Ottoman Empire signed at the end of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), Macedonia was granted to the new autonomous self-governing Principality of Bulgaria. However, the Great Powers, particularly England and Austria grew alarmed with what they saw as extension of Russian power, since Bulgaria was a fellow Slavic Orthodox country that could be easily swayed by Russia. Additionally, they feared that a too rapid collapse of Ottoman rule could create a dangerous power vacuum. Also, Serbia and Greece held some resentment at the establishment of what they saw as a Greater Bulgaria, and felt deprived from the spoils of Ottoman decline.

This prompted the Great Powers to obtain a revision of this treaty. The subsequent Congress of Berlin a few months later was a meeting of the European Great Powers' which revised the Treaty of San Stefano. Although Greece and Serbia succeeded in becoming independent Kingdoms, autonomous from Turkey. Bulgaria's lost much of the territory it had gained, losingThrace and Macedonia back to the Turks. Despite calls for liberation and even the founding of a united Macedonian principality (ie Pan Macedonian), run by a Christian governor, the pleas of the people fell on deaf ears. These events all conspired to create tensions which would spill over into war. The issue of irredentism and nationalism gained great prominence after the creation of Greater Bulgaria and Turkish collapse following the 1878 Treaty of San Stefano. In the first half of 20th Century control over Macedonia was a key point of contention between Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia.

Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia all wished to claim Macedonia, as a key strategic part of their newly formed kingdoms. Throughout the 19th century, each kingdom tried to claim Macedonia as its own. This was done through the medium of church and education, particularly between Greece and Bulgaria. Throught the advancement of Greek or Bulgarian language, and provision of local priests either from the Bulgarian Exarchate or Orthodox Church of Constantinople, an entire village would be claimed to be 'Greek', while its neighbour would be 'Bulgarian'. This ad hoc arrangement did not follow any geographic or ethnic correlates, and occurred at the expense of the development of a local, Macedonian identity, and often involved harassment of peoples in order to profess loyalty to Greece or Bulgaria, and abdicate profession of any independent identity .

Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising and after

Main article: Ilinden-Preobrazhenie UprisingIn 1893 revolutionary organization was established, (later IMARO). This organization advocated the creation of an autonomous Macedonia and Thrace in the Ottoman Empire with the priority of the Bulgarian element. Before 1902, in theory only Bulgarians could join, but afterwards, it invited anyone who lives in Macedonia, whether Greek, Bulgarian or Jew to join together. On August 2, 1903, IMRO led the locals in the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising, named after the festival of the Prophet Elijah on which it began. That was one of the greatest events in the history of the population in the regions of Macedonia and Thrace. The high point of the Ilinden revolution was the establishment of the Krushevo Republic in the town of Krushevo. By November 1903, the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising was suppressed. The uprising was led by the following activists of the IMRO: Yane Sandanski, Nikola Karev, Dame Gruev, Pitu Guli, etc.

The failure of the 1903 insurrection resulted in the eventual split of the IMRO into a left wing (federalist) and a right wing. The left-wing faction opposed Bulgarian nationalism and advocated the creation of a Balkan Socialist Federation with equality for all subjects and nationalities, including Bulgarians. The right-wing fraction of IMRO drifted more and more towards Bulgarian nationalism as its regions became increasingly exposed to the incursions of Serb and Greek armed bands, which started infiltrating Macedonia after 1903. The years 1905-1907 saw lots of violent fighting between IMRO and Turkish forces as well as between IMRO and Greek and Serb detachments.

After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 both fractions laid down their arms and joined the legal struggle. The federalist wing welcomed in the revolution of 1908 and later joined mainstream political life as the People's Federative Party - (Bulgarian section). The right wing formed the Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs and like the PFP participated in Ottoman elections.

The Balkan Wars

Main article: Balkan Wars

During the Balkan Wars former IMRO leaders of both the left and the right wings joined the Macedono-Odrinian Volunteers and fought with the Bulgarian Army. Others like Yane Sandanski with their bands assisted the Bulgarian army with its advance and still others penetrated as far as the region of Kastoria in the Villayet of Monastir. In the Second Balkan War IMRO bands fought the Greeks and Serbs behind the front lines but were subsequently routed and driven out. Notably, Petar Chaulev was one of the leaders of the Ohrid Uprising in 1913 organized jointly by IMRO and the Albanians of Western Macedonia.

The Balkan Wars resulted in important demografic changes to the European territories of the Ottoman empire especially after they were defeated and forced out of the region. What we may call 'Ottoman Macedonia' was divided between the Balkan nations, with its northern parts going to Serbian, the southern to Greece, and the northeastern to Bulgaria.

The wars were an important precursor to World War I, to the extent that Austria-Hungary took alarm at the great increase in Serbia's territory and regional status. This concern was shared by Germany, which saw Serbia as a satellite of Russia. Serbia's rise in power thus contributed to the two Central Powers' willingness to risk war following the assassination in Sarajevo of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria in June 1914.

World War I

See also: Balkans Campaign (World War I)

The attack on the Balkans by the Axis powers was begun by Austria, who initially suffered set backs by fierce Serbian resistance. It was not until Germany sent its troops that broke the resistance and allowed its allies, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria to advance forward. Bulgaria occupied much of Macedonia, advancing into Greek Macedonia too, ever desirous of the area. The IMRO, led by Todor Aleksandrov, maintained its existence in Bulgaria, where it played a role in politics by playing upon Bulgarian irredentism and urging a renewed war to 'liberate' Macedonia. This was one factor in Bulgaria allying itself with Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I. IMRO organised the Valandovo action of 1915, which was an attack on a large Serbian force. The Bulgarian army, supported by the organization's forces, was successful in the first stages of this conflict, managed to drive out the Serbian forces from Vardar Macedonia and came into positions on the line of the pre-war Greek-Serbian border, which was stabilized as a firm front until end of 1918.

In September 1918 the Serbs, British, French and Greeks broke through on the Macedonian front and Tsar Ferdinand was forced to sue for peace. Under the Treaty of Neuilly(November 1919), Bulgaria lost its Aegean coastline to Greece and nearly all of its Macedonian territory to the new state of Yugoslavia, and had to give Dobruja back to the Romanians (see also Western Outlands, Western Thrace).

Аfter the First World War

See also: Vardar Banovina

The territory of the present-day Republic of Macedonia came under the direct rule of Serbia (and later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia), and was sometimes termed "southern Serbia", and, together with a large portion of today's southern Serbia, it belonged officially to the newly formed Vardar Banovina (district). An intense program of Serbianization was implemented during the 1920s and 1930s when Belgrade enforced a Serbian cultural assimilation process on the region. Between the world wars in Serbia, the dialects of Macedonia were treated as a Serbian dialects (UCLA Language Material Sources, ). Only the literary Serbian language was taught, it was the language of government, education, media, and public life; even so local literature was tolerated as a local dialectal folkloristic form. The Serbian National Theatre in Skopje even performed some plays (now the classical drama pieces) in the local language (UCLA Language Material Sources, ).

Greece, like all other Balkan states, adopted restrictive policies towards its minorities, namely towards its Slavic population in its northern regions, due to its experiences with Bulgaria's wars, including the Second Balkan War, and the Bulgarian inclination of sections of its Slavic minority. Many of those inhabiting northeastern Greece fled to Bulgaria and very small group to Serbia (68 families) after the Balkan wars or were exchanged with native Greeks from Bulgaria under a population exchange treaty in the 1920s. Greeks were resettled in the region in two occasions, firstly following the Bulgarian loss of the Second Balkan War when Bulgaria and Greece mutually exchanged their populations in 1919 , and secondly in 1923 as a result of the population exchange with the new Turkish republic that followed the Greek military defeat in Asia minor. Thus Greek Macedonia now came to be Greek dominant for the first time since the 7th century AD.

The Slav speakers that stayed in northwestern Greece were regarded as a potentially disloyal minority and came under severe pressure, with restrictions on their movements, cultural activities and political rights. Many emigrated, for the most part to Canada, Australia, USA and Eastern European countries like Bulgaria. The Greek names for some traditionally Slavic or Turkish speaking areas became official and the Slavic speakers were encouraged to change their Slavic surnames to Greek sounding surnames, e.g. Nachev becoming Natsulis. A similar procedure was applied to Greek names in Bulgaria and Serbian Macedonia (eg. Nevrokopi becoming Goce Delchev ). In Greece, there was a government sponsored process of Hellenization . Many of the border villages were closed to outsiders, ostensibly for security reasons. The Greek government and people have never recognized the existence of a distinct "Macedonian" ethnic group, as the term "Macedonian" is already reserved for the ethnic Greek population that has traditionally inhabited Greece's northern-most region (Macedonia (Greece)). According to Peter Trudgill Slav speakers in northern Greece with a non-Greek national identity have tended to leave Greece. As a result, the overwhelming majority of remaining Slav speakers declare themselves as Greeks (Trudgill P. (2000) "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity" in Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford University Press).

On August 10, 1920, upon signing the Treaty of Sèvres that "measures were being taken towards the opening of schools with instruction in the Slav language in the following school year of 1925/26". Thus, the primer intended for the "Slav-speaking minority" children in Greek Macedonia to learn their native language in school, entitled "ABECEDAR" , was offered as an argument in support of this statement. This primer, prepared by a special government commissioner was published by the Greek government in Athens in 1925, but was printed in a specially adapted Latin alphabet instead of the traditional Cyrillic, since Cyrillic was the official alphabet of the neighboring Bulgaria. Serbian language, on the other hand, uses both Cyrilic and Latin scripts. Nevertheless, the Abecedar schoolbooks were confiscated and destroyed before they got into the reach of the children HRW pg.42.

In 1924 IMRO entered negotiations with the Comintern about collaboration between the communists and the Macedonian movement and the creation of a united Macedonian movement. The idea for a new unified organization was supported by the Soviet Union, which saw a chance for using this well developed revolutionary movement to spread revolution in the Balkans and destabilize the Balkan monarchies. Todor Alexandrov defended IMRO's independence and refused to concede on practically all points requested by the Communists. No agreement was reached besides a paper "Manifesto" (the so-called May Manifesto of 6 May 1924), in which the objectives of the unified Macedonian liberation movement were presented: independence and unification of partitioned Macedonia, fighting all the neighbouring Balkan monarchies, forming a Balkan Communist Federation and cooperation with the Soviet Union.

Failing to secure Alexandrov's cooperation, the Comintern decided to discredit him and published the contents of the Manifesto on 28 July 1924 in the "Balkan Federation" newspaper. IMRO's leaders Todor Aleksandrov and Aleksandar Protogerov promptly denied through the Bulgarian press that they've ever signed any agreements, claiming that the May Manifesto was a communist forgery.

The policy of assassinations was effective in making Serbian rule in Vardar Macedonia feel insecure but in turn provoked brutal reprisals on the local peasant population. Having lost a lot of popular support in Vardar Macedonia due to his policies Ivan Mihailov, a new IMRO leader, favoured the internationalization of the Macedonian question.

He established close links with the Croatian Ustashe and Italy. Numerous assassinations were carried out by IMRO agents in many countries, the majority in Yugoslavia. The most spectacular of these was the assassination of King Alexander I of Yugoslavia and the French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou in Marseille in 1934 in collaboration with the Croatian Ustaše. The killing was carried out by the IMRO terrorist Vlado Chernozemski and happened after the suppression of IMRO following the 19 May 1934 military coup in Bulgaria.

During the 1930s the Comintern prepared a Resolution about the recognition of Macedonian nation. It was accepted by the Political Secretariat in Moscow on January 11, 1934, and approved by the Executive Committee of the Comintern. The Resolution was published for first time in the April issue of Makedonsko Delo under the title ‘The Situation in Macedonia and the Tasks of IMRO (United)’.

Second World War

Further information: Balkans Campaign and National Liberation War of MacedoniaUpon the outbreak of World War II, the government of the Kingdom of Bulgaria declared a position of neutrality, being determined to observe it until the end of the war, but hoping for bloodless territorial gains. But it was clear that the central geopolitical position of Bulgaria in the Balkans would inevitably lead to strong external pressure by both sides of World War II.

Bulgaria was forced to join the Axis powers in 1941, when German troops prepared to invade Greece from Romania reached the Bulgarian borders and demanded permission to pass through Bulgarian territory. Threatened by direct military confrontation, Tsar Boris III had no choice but to join the fascist block, which officially happened on 1 March 1941. There was little popular opposition, since the Soviet Union was in a non-aggression pact with Germany.

On April 6, 1941, despite having officially joined the Axis Powers, the Bulgarian government maintained a course of military passivity during the initial stages of the invasion of Yugoslavia and the Battle of Greece. As German, Italian, and Hungarian troops crushed Yugoslavia and Greece, the Bulgarians remained on the side-lines. The Yugoslav government surrendered on April 17. The Greek government was to hold out until April 30. On April 20, the period of Bulgarian passivity ended. The Bulgarian Army entered the Aegean region. The goal was to gain an Aegean Sea outlet in Thrace and Eastern Macedonia and much of eastern Serbia. The so-called Vardar Banovina was divided between Bulgaria and Italians which occupied West Macedonia.

At the beginning of the war on the Balkans all in Macedonia shows how complicated the situation was. The political sympathies were intertwined with the national feelings. As ruling, the pro-Serbian elements were for the English-French block and the pro - Bulgarian, for the power of Axis. Besides, some of the former revolutionary activists were not far from the thought of solving the Macedonian question through accession of Macedonia or parts of it to Italy. The followers of Ivan Mihaylov fought for pro-Axis and pro-Bulgarian Macedonia. In this situation the population was divided in different groups. And time was crucial.

Thus on April 8th. 1941 in Skopie a meeting was held, where the question: “What had to be done?" was put up. What actions should be undertaken in those crucial days in order not to omit, as it had already happened, the precise moment for liberating Macedonia. On that meeting were present mainly followers of the idea for the liberation through independence of Macedonia, namely: Dimitаr Gjuzelev, Dimitur Chkatrov, Toma Klenkov, Ivan Piperkov and other popular activists of IMRO as well as members of Yugoslav Communist Party(YCP) - Kotse Stojanov, Angel Petkovski and Ilja Neshovski, invited by Trajko Popov. The latter despite a communist, member of YCP, was an active follower of the idea of IMRO for the creation of a pro-Bulgarian, Macedonian state under German and Italian protection. But the situation changed dynamically.

As ten days later the Bulgarian army entered Yugoslav Vardar Macedonia on April 19th. 1941, it was greeted by most of the population as liberators. Former IMRO members were active in organising Bulgarian Action Committees charged with taking over the local authorities. Some former IMRO (United) members such as Metodi Shatorov , who were leading member of the Yugoslav Communist Party, also refused to define the Bulgarian forces as occupiers (contrary to instructions from Belgrade) and called for the incorporation of the local Macedonian Communist organizations within the Bulgarian Communist Party. This policy changed towards 1943 with the arrival of the Montenegrin Svetozar Vukmanović-Tempo, who began in earnest to organize armed resistance to the Bulgarian occupation. Many former IMRO members assisted the authorities in fighting Tempo's partisans.

IMRO was also active in organizing the resistance of the Bulgarian population in Aegean Macedonia against Greek nationalist and communist regiments. With the help of Mihailov and Macedonian emigrants in Sofia, several pro-German armed detachments - Uhrana were organized in the Kostur, Lerin and Voden districts of Greek Macedonia in 1943-44. These were led by Bulgarian officers originally from Aegean Macedonia - Andon Kalchev and Georgi Dimchev.

Local recruits and volunteers formed the Bulgarian 5th Army, based in Skopje, which was responsible for the round-up and deportation of over 7,000 Jews in Skopje and Bitola. Harsh rule by the occupying forces encouraged some Macedonians to support the Communist Partisan resistance movement of Josip Broz Tito. In Greece, it has been estimated that the military wing of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) had 14 000 soldiers of Slavic Macedonian origin out of total 20 000 fighters. Some Macedonians which had been supporters of Communist partisan movement few in the Italian occupied area to Tito's Partisan resistance movement, fighting the occupying Bulgarians, Germans and Italians as well as opposing the Serbian royalist Chetniks. The Macedonian resistance at the end of the war had a strongly nationalist character, not at least as a reaction to Serbia's pre-war repression.

On the 2nd of August 1944 in the St. Prohor Pchinski monastery at the Antifascist assembly of the national liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) with Panko Brashnarov (the former IMRO revolutionary from the Ilinden period and the IMRO United) as a first speaker, the modern Macedonian state was officially proclaimed, as a federal state within Tito's Yugoslavia, receiving recognition from the Allies.

On 5 September 1944, the Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria and invaded the country. Within three days the Soviets occupied the northeastern part of Bulgaria along with the key port cities of Varna and Burgas. The Bulgarian Army was ordered to offer no resistance to the Soviets. On 8 September 1944, the Bulgarians changed sides and joined the Soviet Union in its war against Nazi Germany.

After the declaration of war by Bulgaria on Germany, Ivan Mihailov - the IMRO leader arrived in German occupied Skopje, where the Germans hoped that he could form an Macedonian state with their support. Seeing that the war is lost to Germany and to avoid further bloodshed, he refused. The Bulgarian troops, surrounded by German forces and betrayed by high-ranking military commanders, fought their way back to the old borders of Bulgaria. Three Bulgarian armies (some 500,000 strong in total) entered Yugoslavia in September 1944 and moved from Sofia to Niš and Skopje with the strategic task of blocking the German forces withdrawing from Greece. Southern and eastern Serbia and Macedonia were liberated within a month.

Macedonians after the Second World War

See also: Socialist Republic of Macedonia

The People’s Republic of Macedonia was proclaimed at the first session of the ASNOM (on St. Elia's Day – August 2, 1944). The Macedonian language was proclaimed the official language of the Republic of Macedonia at the same day. The first document written in the literary standard Macedonian language is the first issue of the Nova Makedonia newspaper in autumn 1944. Later, by special Act, it became a constitutive part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In the next 50 years Republic of Macedonia was part of the Yugoslav federation.

Vormer members of the IMRO (United) which participated in CPY, ASNOM and the forming of Republic of Macedonia as a federal state of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia as Panko Brashnarov, Pavel Shatev, Dimitar Vlahov and Venko Markovski were quickly ousted from the new government. Such Macedonian activists came from Bulgarian Communist Party, have declared Bulgarian ethnicity before WWII never managed to get rid of their pro-Bulgarian bias and because of that, the first and second one were annihilated. As last survivor among the communists associated with the idea of Macedonian autonomy Dimitar Vlahov was used "solely for window dressing". They ware chanched (sicsic) from cadres loyal to the Yugoslav Communist Party in Belgrade, who had has pro-Serbian leanings and education before the war. It was not important that thеse party members have declared Bulgarian origin during the war, as for example Kiro Gligorov, Mihajlo Apostoloski and Lazar Koliševski.

Following the war, Tito separated Yugoslav Macedonia from Serbia, making it a republic of the new federal Yugoslavia (as the Socialist Republic of Macedonia) in 1946. He also promoted the concept of a separate Macedonian nation, as a means of severing the ties of the Slav population of Yugoslav Macedonia with Bulgaria, although the Macedonian language is close to and largely mutually intelligible with Bulgarian, and to a lesser extent Serbian. The differences were emphasized and the region's historical figures were promoted as being uniquely Macedonian (rather than Bulgarian or Serbian). A separate Macedonian Orthodox Church was established, splitting off from the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1967 (only partly successfully, because the church has not been recognized by any other Orthodox Church). The ideologists of a separate and independent Macedonian country, same as the pro-Bulgarian sentiment, was forcibly suppressed.

Tito had a number of reasons for doing this. First, he wanted to reduce Serbia's dominance in Yugoslavia; establishing a territory formerly considered Serbian as an equal to Serbia within Yugoslavia achieved this effect. Secondly, he wanted to sever the ties of the Macedonian population with Bulgaria as recognition of that population as Bulgarian could have undermined the unity of the Yugoslav federation. Thirdly, Tito sought to justify future Yugoslav claims towards the rest of geographical Macedonia; in August 1944, he claimed that his goal was to reunify "all parts of Macedonia, divided in 1915 and 1918 by Balkan imperialists." To this end, he opened negotiations with Bulgaria for a new federal communist state (see Bled agreement), which would also probably have included Albania, and supported the Greek Communists in the Greek Civil War. The idea of reunification of all of Macedonia under Communist rule was abandoned in 1948 when the Greek Communists lost the civil war and Tito fell out with the Soviet Union and pro-Soviet Bulgaria.

Tito's actions had a number of important consequences for the Macedonians. The most important was, obviously, the promotion of a distinctive Macedonian identity as a part of the multi-ethnic society of Yugoslavia. The process of ethnogenesis, started earlier, gained momentum, and a distinct national Macedonian identity was formed. There have been numerous accounts from northern Macedonia from the late 1940s that the policy of Bulgarisation during the Bulgarian occupation (1941 - 1944) was no effective for the ordinary Macedonian as the policy of Serbianisation until then. IMRO's leader in exile, Ivan Mihailov, and the renewed Bulgarian IMRO after 1990 have, on the other hand, repeatedly argued that between 120,000 and 130,000 people went through the concentration camps of Idrizovo and Goli Otok for pro-Bulgarian sympathies or ideas for independent Macedonia in the late 1940s. This has also been confirmed by former prime minister Ljubco Georgievski .

The critics of these claims question the number as it would implied roughly a third of the male Christian population at that time. And the reasons of imprisonment, they argue, were multiple as there were Macedonian nationalists, Stalinists, Middle class members, Albanian nationalists and everybody else who was either against the post war regime or denounced as one for whatever reasons. Unlike the time before WWII, when Macedonia was hotbed for unrest and terror and about 60% of the entire royal Yugoslav police force was stationed there , after the war there were no signs of disturbances comparable with pre-war times or post war times in other parts of former Yugoslavia, such as Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia. . Whatever the truth, it was certainly the case that most Macedonians embraced their official recognition as a separate nationality. Even so, some pro-Bulgarian or pro-Serbian sentiment persisted despite government suppression; even as late as 1991, convictions were still being handed down for pro-Bulgarian statements.

After the Second World War, ethnic Macedonians living in Greece organized themselves in NOF in 1945, and started fighting against the right-wing government in Athens. In 1946 NOF agreed to unite with the Democratic Army of Greece and start a join fight (see: Greek Civil War). Many of the slavophone Macedonians who lived in Greece either chose to emigrate to Communist countries (especially Yugoslavia) to avoid prosecution for fighting on the side of the Greek communists. Although there was some liberalization between 1959 and 1967, the Greek military dictatorship re-imposed harsh restrictions. The situation gradually eased after Greece's return to democracy, but Greece still receives criticism for its treatment of some slavophone Macedonian political organizations. Greece, however, recognizes the Rainbow political party of the slavophone Macedonians who canvas during elections.

The Macedonians in Albania faced restrictions under the Stalinist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha, though ordinary Albanians were little better off. Their existence as a separate minority group was recognized as early as 1945 and a degree of cultural expression was permitted.

As ethnographers and linguists tended to identify the population of the Bulgarian part of Macedonia as Bulgarian in the interwar period, the issue of a Macedonian minority in the country came up as late as the 1940s. In 1946, the population of Blagoevgrad Province was declared Macedonian and teachers were brought in from Yugoslavia to teach the Macedonian language. The census of 1946 was accompanied by mass repressions, the result of which was the complete destruction of the local organizations of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization and mass internments of people at the Belene concentration camp. The policy was reverted at the end of the 1950s and later Bulgarian governments argued that the two censuses of 1946 and 1956 which recorded up to 187,789 Macedonians (of whom over 95% were said to live in Blagoevgrad Province, also called Pirin Macedonia) were the result of pressure from Moscow. Western governments, however, continued to list the population of Blagoevgrad Province as Macedonian until the beginning of the 1990s despite the 1965 census which put Macedonians in the country at 9,630. The two latest censuses after the fall of Communism (in 1992 and 2001) have, however, confirmed the results from previous censuses with some 3,000 people declaring themselves as "Macedonians" in Blagoevgrad Province in 2001 (<1.0% of the population of the region) out of 5,000 in the whole of Bulgaria.

Macedonians after the establishment of independent Macedonian state

Main article: Republic of MacedoniaThe country officially celebrates 8 September 1991 as Independence day, with regard to the referendum endorsing independence from Yugoslavia, albeit legalizing participation in "future union of the former states of Yugoslavia". The Republic of Macedonia remained at peace through the Yugoslav wars of the early 1990s. A few very minor changes to its border with Yugoslavia were agreed upon to resolve problems with the demarcation line between the two countries. However, it was seriously destabilized by the Kosovo War in 1999, when an estimated 360,000 ethnic Albanian refugees from Kosovo took refuge in the country. Although they departed shortly after the war, soon after, Albanian radicals on both sides of the border took up arms in pursuit of autonomy or independence for the Albanian-populated areas of the Republic.

A short conflict was fought between government and ethnic Albanian rebels, mostly in the north and west of the country, between March and June 2001. This war ended with the intervention of a NATO ceasefire monitoring force. In the Ohrid Agreement, the government agreed to devolve greater political power and cultural recognition to the Albanian minority.

In this period it has been claimed by Macedonian scholars that there exist large and oppressed ethnic Macedonian minorities in the region of Macedonia, located in neighboring Albania (up to 35,000 people), Bulgaria (up to 200,000, mainly in Blagoevgrad Province), Greece (up to 250 000 in Greek Macedonia) and Serbia (about 20,000 in Pčinja District). Because of those claims, irredentist proposals are being made calling for the expansion of the borders of the Republic of Macedonia to encompass the territories allegedly populated with ethnic Macedonians, either directly or through initial independence of Blagoevgrad province and Greek Macedonia, followed by their incorporation into a single state. (See United Macedonia). The population of the neighboring regions is presented as "subdued" to the propaganda of the governments of those neighbouring countries, and in need of "liberation".

Because separate ethnic status of Macedonians is by some accounts not fully recognized in Bulgaria and Greece, there can be only speculation about the actual numbers, including the possibility that there is no Macedonian minority at all in those countries.

The supporters of Macedonism generally ignore censi conducted in Albania, Bulgaria and Greece, which show minimal presence of ethnic Macedonians. They consider those censi flawed, without presenting evidence in support, and accusing the governments of neighboring countries of continued propaganda. During this period, ethnic Macedonians living in the region continue to complain of official harassment. This was confirmed in 2005 by the European Court of Human Rights with a judgment whereby Bulgaria was sentenced to pay damages amounting to 6800 euros for a violation of Article 11 (freedom of assembly and association) of the European Convention on Human Rights for its refusal to give court registration to "UMO Ilinden-Pirin", the Macedonian political party in Bulgaria.

A similar judgment was passed against Greece for also violating Article 11 in regards of the members of the Greek far-left Rainbow party, which claims to be the "Party of the Macedonian minority in Greece" despite the fact that it enjoys minimal public support in the area where the minority purportedly lives.

Symbols

|

|

- Sun: The official flag of the Republic of Macedonia, adopted in 1995, is a yellow sun with eight broadening rays extending to the edges of the red field.

- Coat of Arms: After independence in 1992, the Republic of Macedonia retained the coat of arms adopted in 1946 by the People's Assembly of the People's Republic of Macedonia on its second extraordinary session held on July 27, 1946, later on altered by article 8 of the Constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Macedonia. The coat-of-arms is composed by a double bent garland of ears of wheat, tobacco and poppy, tied by a ribbon with the embroidery of a traditional folk costume. In the center of such a circular room there are mountains, rivers, lakes and the sun; where the ears join there is a red five-pointed star, a traditional symbol of Communism. All this is said to represent "the richness of our country, our struggle, and our freedom".

Unofficial symbols

- Lion: The lion first appears in 1595 in the Korenich-Neorich coat of arms, where the coat of arms of Macedonia is included among with those of eleven other countries. On the coat of arms is a crown, inside a yellow crowned lion is depicted standing rampant, on a red background. On the bottom enclosed in a red and yellow border is written "Macedonia". Later versions of these coat of arms include a more detailed crown and lion with the word "Macedonia" written in a scroll like style. These coat of arms have also been adopted as the official emblem of VMRO-DPMNE, a Macedonian political party. Initially, it was adopted as a state symbol by Bulgaria.

- Vergina Sun: (official flag, 1992-1995) The Vergina Sun is occasionally used to represent the Macedonian people by the diaspora through associations and cultural groups. The Vergina Sun is believed to have been associated with ancient Macedonian kings such as Alexander the Great and Philip II. The symbol was discovered in the Greek region of Macedonia and Greeks regard it as an exclusively Greek symbol, unrelated to Slavic cultures and it is copyrighted under WIPO as a State Emblem of Greece . The Vergina sun on a red field was the first flag of the independent Republic of Macedonia, until it was removed from the state flag under an agreement reached between the Republic of Macedonia and Greece in September 1995. Nevertheless, the Vergina sun is still used unofficially as a national symbol by some groups in the country along with the new state flag.

See also

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- Bulgarians

- A list of prominent ethnic Macedonians

- Macedonian Canadians

- Ethnogenesis

- Macedonism

References

Notes

- Keith Brown, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-691-09995-2.

- Jane K. Cowan (ed.), Macedonia: The Politics of Identity and Difference, Pluto Press, 2000. A collection of articles.

- Loring M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, Princeton University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-691-04356-6.

- Anastasia N. Karakasidou, Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990, University Of Chicago Press, 1997, ISBN 0-226-42494-4. Reviewed in Journal of Modern Greek Studies 18:2 (2000), p465.

- Peter Mackridge, Eleni Yannakakis (eds.), Ourselves and Others : The Development of a Greek Macedonian Cultural Identity since 1912, Berg Publishers, 1997, ISBN 1-85973-138-4.

- Hugh Poulton, Who Are the Macedonians?, Indiana University Press, 2nd ed., 2000. ISBN 0-253-21359-2.

- Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Praeger Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0-275-97648-3.

- Τάσος Κωστόπουλος, Η απαγορευμένη γλώσσα: Η κρατική καταστολή των σλαβικών διαλέκτων στην ελληνική Μακεδονία σε όλη τη διάρκεια του 20ού αιώνα (εκδ. Μαύρη Λίστα, Αθήνα 2000).

External links

- 2002 census

- 2001 census,

- 2006 Census

- 2004 est.

- 2004 census

- 2002 Community Survey

- 2001 census

- 2002 census

- 2000 census

- 2001 census

- 2001 census

- 1989 census

- 2001 census

- 2002 census

- 2003 census

- 2005 census

- 2002 census

- When the name Macedonians is to refer to ethnic Macedonians, it can be considered offensive by Greeks, especially those from Macedonia in northern Greece.

- "Macedonian Slavs" can be translated into Macedonian as Македонски Словени (Makedonski Sloveni). Although acceptable in the past, current use of this name in reference to both the ethnic group and the language can be considered pejorative and offensive by some ethnic Macedonians. The Slav Macedonians in Greece were happy to be acknowledged as Slavomacedonians. A native of Greek Macedonia, a pioneer of Slav Macedonian schools in the region and a local historian, Pavlos Koufis, wrote in Laografika Florinas kai Kastorias (Folklore of Florina and Kastoria), Athens 1996, that (translation by User:Politis),

“ the KKE recognised that the Slavophone population was ethnic minority of Slavomacedonians]. This was a term, which the inhabitants of the region accepted with relief. Slavomacedonians = Slavs+Macedonians. The first section of the term determined their origin and classified them in the great family of the Slav peoples.”

The Greek Helsinki Monitor reports:

: "... the term Slavomacedonian was introduced and was accepted by the community itself, which at the time had a much more widespread non-Greek Macedonian ethnic consciousness. Unfortunately, according to members of the community, this term was later used by the Greek authorities in a pejorative, discriminatory way; hence the reluctance if not hostility of modern-day Macedonians of Greece (i.e. people with a Macedonian national identity) to accept it." - Artan Hoxha and Alma Gurraj Local Self-GOvernment and Decentralization: Case of Albania. History, Reformes and Challenges. In: Local Self Government and Decentralization in South - East Europe. Proceedings of the workshop held in Zagreb, Croatia 6 April, 2001. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Zagreb Office, Zagreb 2001, pp 194-224 ,

- ^ The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, (a) pg. 221 (b) pg. 51, by Loring M. Danforth, ISBN 0-691-04356-6 Cite error: The named reference "Loring M. Danforth" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Пътуване по долините на Струма, Места и Брегалница. Битолско, Преспа и Охридско. Васил Кънчов (Избрани произведения. Том I. Издателство “Наука и изкуство”, София 1970)

- (ETHNOGRAPHIE VON MAKEDONIEN, Geschichtlich-nationaler, spraechlich-statistischer Teil von Prof. Dr. Gustav Weigand, Leipzig, Friedrich Brandstetter, 1924, Превод Елена Пипилева)

- "Macedonia :: History. -- Encyclopaedia Britannica". Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- Coon, Carleton Stevens. The Races of Europe. Greenwood Press Reprint. ISBN 0-8371-6328-5., Chapter XII, section 15

- Theophilactus Simocatta. Historae. Ed. C. de Boor. Lipsiae, 1887, p.259

- "Acta Sancti Demetrii", V 195-207, Гръцки извори за българската история, 3, стр. 159-166 (Medieval Greek, Bulgarian)

- Lundman, Bertil J. - The Races and Peoples of Europe (New York: IAAEE. 1977)

- Petlichkovski A, Efinska-Mladenovska O, Trajkov D, Arsov T, Strezova A, Spiroski M (2004). "High-resolution typing of HLA-DRB1 locus in the Macedonian population". Tissue Antigens. 64 (4): 486–91. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00273.x. PMID 15361127.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ivanova M, Rozemuller E, Tyufekchiev N, Michailova A, Tilanus M, Naumova E (2002). "HLA polymorphism in Bulgarians defined by high-resolution typing methods in comparison with other populations". Tissue Antigens. 60 (6): 496–504. PMID 12542743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bulgarian Bone Marrow Donors Registry—past and future directions - Asen Zlatev, Milena Ivanova, Snejina Michailova, Anastasia Mihaylova and Elissaveta Naumova, Central Laboratory of Clinical Immunology, University Hospital “Alexandrovska”, Sofia, Bulgaria, Published online: 2 June 2007

- The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communsism. D P Hupchik

- Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe - Southeast Europe (CEDIME-SE) MINORITIES IN SOUTHEAST EUROPE - Macedonians of Bulgaria, pg. 6

- Paul Fouracre. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Medieval History

- The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World - Loring M. Danforth, ISBN13: 978-0-691-04356-2

- The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica.

- The Races and Religions of Macedonia, "National Geographic", Nov 1912.

- Carnegie Endowment for International peace.REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION. To Inquire into the causes and Conduct OF THE BALKAN WARS, PUBLISHED BY THE ENDOWMENT WASHINGTON, D.C. 1914

- Europe since 1945. Encyclopedia by Bernard Anthony Cook. ISBN 0815340583, pg. 808.

- Paul Fouracre. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Medieval History

- The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World - Loring M. Danforth, ISBN13: 978-0-691-04356-2

- Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe - Southeast Europe (CEDIME-SE)MINORITIES IN SOUTHEAST EUROPE - Macedonians of Bulgaria, pg. 33.

- Encyclopedia of Greece & the Hellenic Tradition, Volume II, Editor: Graham Speake

- The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, C. 500-700 by Florin Curta, ISBN 0-521-80202-4

- The new Cambridge Medieval History, Volume I, Editor Paul Fouracre

- Medieval Encyclopedia, VOlume II

- "Средновековни градови и тврдини во Македониjа", Скопjе, "Македонска цивилизациjа", 1996 (Macedonian). Part of the book here.

- THe Balkans. From Constantinople to Communsims. Dennis P Hupchik

- What Does the Future Hold for Mankind by R A Bowland, ISBN 1-4010-4043-8

- ^ Who Are the Macedonians?, Page 19, by Hugh Poulton, ISBN 1-85065-534-0 Cite error: The named reference "Hugh Poulton" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. D P Hupchik

- Atlas of Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century, Page 17, by R J Crampton, ISBN 0-415-06689-1

- Floudas, Demetrius Andreas; ""FYROM's Dispute with Greece Revisited"" (PDF). in: Kourvetaris et al (eds.), The New Balkans, East European Monographs: Columbia University Press, 2002, p. 85.