This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Theathenae (talk | contribs) at 21:55, 4 July 2005 (→The Ancient Macedonians: makednós is an ancient Greek adjective in its own right and this is not open to modern linguists' interpretation). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:55, 4 July 2005 by Theathenae (talk | contribs) (→The Ancient Macedonians: makednós is an ancient Greek adjective in its own right and this is not open to modern linguists' interpretation)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Antiquity and the Roman Empire

Macedonia is known to have been inhabited from Neolithic times. Early inhabitants of the region were the Thracians, the Paionians, and probably some Illyrians. The Macedonians lived along the Aliákmon and later along the lower course of the Axios, and steadily expanded into the rest of Macedonia, displacing, conquering, or absorbing the earlier inhabitants. Thracians occupied mainly the eastern parts of Macedonia (Mygdonia, Crestonia, Bisaltia). Paionian tribes occupied the northern part of Macedonia, which was known as the kingdom of Paionia before it was conquered by Macedon. Lynkestae and Elimiots (who Thucydides referred to as "Macedonian tribes by blood": Thuc., Pelop. 2.99) and Paionians dwelt in western Macedonia.

The Ancient Macedonians

Main article: Macedon.

According to ancient Greek mythology, Macedon - ancient Greek ΜΑΚΕΔΩΝ (Makedōn), poetic ΜΑΚΗΔΩΝ (Makēdōn) - was the name of the first phylarch (tribal chief) of the ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΕΣ (Makedónes). The only surviving historical reference on the ethnic origin of the Macedonians comes from the Greek historian Herodotus, who in his Histories states that the Macedonians were a Dorian tribe left behind during the great Dorian invasion ("ΜΑΚΕΔΝΩΝ ΚΑΛΕΟΜΕΝΩΝ" - Histories 1.56.1). The region of Macedonia (Gr. ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΙΑ) most likely took its name from this tribe, which according to Herodotus was called Makednoi (ΜΑΚΕΔΝΟΙ). The word "Makednos" derives from the Doric Greek word ΜΑΚΟΣ - "makos" (Attic form ΜΗΚΟΣ - "mékos"), which is Greek for "length". This theory seems to be in agreement with Herodotus' records. According to scholars Macedonians took this name either because they were physically tall, or because they settled in the mountains. The latter definition would translate "Macedonian" as "Highlander". Another ancient historical account on the Macedonians, is an Iranian inscription which dates at 513BC (now in Teheran museum), where the Persian king refers to the conquered Macedonians as Yauna Takabara (The Greeks wearing big hats). Most academics take the view that the ancient Macedonians probably spoke either a language that was either an idiom of the North-Western Greek dialect group (related to Doric and Aeolic), or a language very closely related to Greek which would form a Graeco-Macodonian or Hellenic branch. The discussion about their origin started as early as the 19th century. Two major opinions have been phrased, the first regards them as being initially Greek whereas the second recognizes them as a distinct tribe (yet closely akin to the Greeks) which was completely Hellenized over time. This difference in opinions is caused mainly by contradictory ancient accounts. For example Demosthenes denounced the Macedonians, dismissing Philip II as being "not only not a Greek nor related to the Greeks, but not even a barbarian from a land worth mentioning; no, he's a pestilence from Macedonia, a region where you can't even buy a slave worth his salt". It is probable that due to the highly dense political climate of Athens, Demosthenes and the anti-Macedonian party were using raw insults against the idea of a non-Athenian leadership in Greece. The Athenian poet Strattis in his comedy "Macedonians" of around 400 BC writes of a dialogue between an Athenian and a Macedonian where the first asks a question using his Attic dialect and the Macedonian responds using his own dialect, which is represented as a form of Greek. ("Strattis, passage 28" Edmonds, J.M. The Fragments of Attic Comedy. Leiden:Brill,1957). Furthermore, all the inscriptions found in the area of Macedonia were written in Greek and much of the Macedonian vocabulary known to us from ancient quotations (about 700 words including names, cities, gods, months, feasts and common words) is clearly Greek. Some scholars view the Pella katadesmos, written in a form of Doric Greek, as the first discovered Macedonian text.

Herodotus also records that Alexander I of Macedon was tested by the Elians on whether he's Greek or not. Herodotus writes: "the Greeks who were to run against him wanted to bar him from the race, saying that the contest should be for Greeks and not for foreigners. Alexander, however, proving himself to be an Argive, was judged to be a Greek." (Histories, 5:22). Inscriptions of Macedonian Olympic winners survive from the 5th century BC. Similarly there are texts such as the Embassy of Aeschines, which reveal to us that Macedon in fact took place in the pan-Hellenic events (held only for Greek states) before Philip II: For at a congress of the Lacedaemonian allies and the other Greeks, in which Amyntas, the father of Philip, being entitled to a seat, was represented by a delegate whose vote was absolutely under his control, he joined the other Greeks in voting to help Athens to recover possession of Amphipolis. As proof of this I presented from the public records the resolution of the Greek congress and the names of those who voted (Aeschines - On the Embassy 2.32).

However there are some Classical texts, in which there's often an implied differentiation between Macedonians and Greeks, perhaps because Macedon had not adapted the polis, and followed a Mycenaean-style of monarchic government. In that respect, the culturally backwards kingdom of Macedon at the time of Philip II, was envied and frowned at by the once mighty city-states of mainland Greece. Eventually sources from post-Classic times reveal that after Alexander's conquests, Macedon had finally acquired a significant place in the Greek World. Despite all those facts, it is certain that the Macedonian people viewed themselves proudly as Greeks, no different than the Athenians and the Thebans. This becomes evidence from ancient historical sources which contain quotations of Macedonians:

- ...you have shown your contempt for right and your hostility to me by actually sending an embassy to urge the king of Persia to declare war on me. This is the most amazing exploit of all; for, before the king reduced Egypt and Phoenicia,1 you passed a decree calling on me to make common cause with the rest of the Greeks against him, in case he attempted to interfere with us... (Philip II to the Athenians, Demosthenes - Speeches 11-20).

- The Aitolians, the Akarnanians, the Macedonians, men of the same language, are united or disunited by trivial causes that arise from time to time; with aliens, with barbarians, all Greeks wage and will wage eternal war; for they are enemies by the will of nature, which is eternal, and not from reasons that change from day to day. (Livy - The foundation of the city, par. 31)

- He sent to Athens three hundred Persian panoplies to be set up to Athena in the acropolis; he ordered this inscription to be attached: Alexander (of Philip) and the Greeks, except the Lacedaemonians, set up these spoils from the barbarians dwelling in Asia (Arrian - Anabasis, 1.16.7)

- Your ancestors invaded Macedon and the rest of Greece and did us harm although we had not done you any previous injury. I have been appointed commander-in-chief of the Greeks and it is with the aim of punishing the Persians that I have crossed into Asia, since you are the aggressors. (Alexander the Great to Darius, Arrian, Alexander’s Anabasis – 2.14)

- Now you fear punishment and beg for your lives, so I will let you free, if not for any other reason so that you can see the difference between a Greek king and a barbarian tyrant, so do not expect to suffer any harm from me. A king does not kill messengers. (Alexander the Great to the Persians, Kallisthenes 1.37.9-13).

The Roman Empire

By the 4th century AD, the time of the inclusion of the region into the Roman Empire, most of southern Macedonia with the lower courses of the Aliákmon, Vardar, Strymon (Struma) and Nestos (Mesta) rivers was completely Hellenized. Northern Macedonia, by contrast, was largely Latinized, while the Thracian and Illyrian tribes in the mountains generally preserved their languages.

Macedonia was ravaged several times in the 4th and the 5th century by desolating onslaughts of Visigoths, Huns and Vandals. These did little to change its ethnic composition but left much of the region depopulated.

Middle Ages

The Slavs took advantage of the desolation left by the nomadic tribes and in the 6th century settled the Balkan Peninsula, including Macedonia. Reaching as far south as Thessaly and the Peloponnese, they settled in regions that were called Sclavinias, which gradually got eliminated by the Byzantine Emperors. The Romanized Illyrian and Thracian population of Macedonia was pushed to the mountains. Many scholars today consider that present-day Aromanians (Vlachs) and Albanians originate from this mountainous population. The interaction between Romanised and non-Romanised Illyrians and Thracians and the Slavs resulted in linguistic similarities which are reflected in modern Bulgarian, Albanian, Romanian and Macedonian, all of them members of the Balkan linguistic union. The Slavs occupied also the hinterland of Thessaloniki launching consecutive attacks on the city in 584, 586, 609, 620, and 622 AD. The Slavs were often joined in their onslaughts by detachments of Avars but these did not form any lasting settlements in the region. A branch of the Bulgars led by khan Kuber, however, settled western Macedonia and eastern Albania around 680 AD and also engaged in attacks on Byzantium together with the Slavs.

At the beginning of the 9th century, Bulgaria conquered most of Macedonia, with the exception of Thessaloniki and the Aegean littoral. The region remained under Bulgarian rule for two centuries, until the conquest of Bulgaria and the reincorporation of Macedonia by the Byzantine Emperor Basil II (nicknamed the Bulgar-slayer) in 1018. After the adoption of Christianity in 865 AD and of Old Church Slavonic as the official language of the Bulgarian Church in 893, Slavs and Bulgars in Bulgaria were generally referred to by Byzantine, West European, as well as Bulgarian sources as only Bulgarian (Bulgar) or as "Slav-Bulgarian".

In the 11th and the 12th century, the first mention was made of two non-Greek ethnic groups just off the borders of Macedonia: Arvanites in modern Albania and Vlachs (Aromanians) in Thessaly and Pindus. Modern historians are divided as to whether the Albanians came to the Balkans then or originated from the native non-Romanized Thracian, Paionian, or Illyrian populations.

Also in the 11th century Byzantium settled several tens of thousand Turkic Christians from Asia Minor, referred to as "Vardariotes", along the lower course of the Vardar. Colonies of other Turkic tribes such as Uzes, Petchenegs, and Cumans were also introduced at various periods from the 11th to the 13th century. All these were eventually Hellenized or Bulgarized. Roma, migrating from north India reached the Balkans, including Macedonia, around the 14th century with some of them settling there. There were successive waves of Roma immigration in the 15th and the 16th century, too.

In the 13th and the 14th century, Macedonia was contested by the Byzantine Empire, the Latin Empire, Bulgaria and Serbia but the frequent shift of borders did not result in any major population changes.

Ottoman Rule

Muslims and Christians

The initial period of Ottoman rule led to the complete desolation of the plains and river valleys of Macedonia. The Christian population there was slaughtered, escaped to the mountains or was forcefully converted to Islam. Turkish colonists were largely brought from Asia Minor and settled, for the most part, in southern Macedonia and along the Vardar. Towns destroyed during the conquest were renewed, this time populated exclusively by Muslims. The Turkish element in Macedonia was especially strong in the 17th and the 18th century with travellers defining the majority of the population, especially the urban one, as Muslim. The Turkish population, however, sharply declined at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century on account of the incessant wars led by the Ottoman Empire, the low birth rate and the higher death toll of the frequent plague epidemics among Muslims than among Christians.

The Christian population was subjected to extensive processes of forceful Islamization during the 17th and the 18th century, which affected chiefly the peasant Bulgarian population of several strategic mountain districts. Mass Islamization of Greeks also took place, though on a smaller scale in the southwestern Macedonian districts of Grevena and Kozani. The Ottoman-Habsburg war (1683-1699), the subsequent flight of a substantial part of the Serbian population in Kosovo to Austria and the reprisals and looting during the Ottoman counteroffensive led to an influx of Albanian Muslims to northern and northwestern Macedonia. Being in the position of power, the Albanians managed to push out their Christian neighbours and conquered additional territories in the 18th and the 19th century. The repeated plundering of the important Aromanian city of Moscopole and other Aromanian settlements in eastern Albania in the second half of the 18th century caused a large-scale Aromanian emigration to the Macedonian cities and towns, most notably to Bitola, Krushovo and Thessaloniki. Thessaloniki became also the home of a large Jewish population following Spain's expulsions of Jews after 1492. The Jews later formed small colonies in other Macedonian cities, most notably Bitola and Serres.

The Hellenic Idea

The rise of European nationalism in the 18th century led to the spread of the Hellenic idea in Macedonia. Under the influence of the Greek schools and the Patriarchate of Constantinople the urban Christian population of Slavic, Vlach and Albanian origin started to view itself increasingly more as Greek. The Greek language became a symbol of civilization and a basic means of communication between non-Muslims. The process of Hellenization was additionally reinforced after the abolition of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid in 1767. Though with a predominantly Greek clergy, the Archbishopric did not yield to the direct order of Constantinople and had autonomy in many vital domains. The poverty of the Christian peasantry and the lack of proper schooling in villages preserved the linguistic diversity of the Macedonian countryside and averted the possibility of complete Hellenization of the region. The Greek War of Independence (1821-1829), however, dealt a nearly fatal blow to the Hellenic idea in Macedonia. The flight of the Macedonian intelligentsia to independent Greece and the mass closures of Greek schools by the Ottoman authorities weakened the Hellenic presence in the region for a century ahead.

The Bulgarian Idea

The Slavs in Macedonia continued to call themselves Bulgarians during the first four centuries of Ottoman rule and were described as such by Ottoman historians like Evliya Celebi and Sa'aedin. The name meant, however, rather little in view of the political oppression by the Ottomans and the religious and cultural one by the Greek clergy. The Slavonic language was preserved as a cultural medium only in a handful of monasteries, to rise in terms of social status for the ordinary Bulgarian usually meant quick and irrevocable Hellenisation.

Although the first literary work in Modern Bulgarian, History of Slav-Bulgarians was written by a Macedonian-born monk, Paisiy of Hilendar as early as 1762, it took almost a century for the Bulgarian idea to regain ascendancy in the region. The Bulgarian advance in Macedonia in the 19th century was aided by the numerical superiority of the Slavs after the decrease in the Turkish population, as well as by their improved economic status. The Slavs of Macedonia took active part in the struggle for independent Bulgarian Patriarchate and Bulgarian schools. The representatives of the intelligentsia wrote in a language which they called Bulgarian and strove for a more even representation of the dialects spoken in Macedonia in formal Bulgarian. The autonomous Bulgarian Exarchate established in 1870 included northwestern Macedonia. After the overwhelming vote of the districts of Ohrid and Skopje, it grew to include the whole of present-day Vardar and Pirin Macedonia in 1874.

This process of “Bulgarification” of Macedonia, however, was much less successful in southern Macedonia, which beside Slavs had compact Greek and Hellenified Aromanian population. The Hellenic idea and the Patriarchate of Constantinople preserved much of their earlier influence among the local Slavs and the arrival of the Bulgarian propaganda turned the region into a battlefield between Slavs owing allegiance to the Patriarchate and the Exarchate with division lines often separating family and kin.

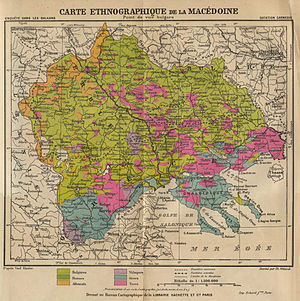

Independent Point of View

European ethnographs and linguists until the Congress of Berlin usually regarded the language of the Slavic population of Macedonia as Bulgarian. French scholars A. Boue in 1840 and G. Lejean in 1861, Germans A. Griesebach in 1841, J. Hahn in 1858 and 1863, A. Petermann in 1869 and H. Kiepert in 1876, Slovak Safarik in 1842 and the Czechs J. Erben in 1868 and F. Brodaska in 1869, Englishmen Wyld in 1877 and G. M. Mackenzie and A.P. Irby in 1863, Serbians Davidovitch in 1848, Desjardins in 1853 and S. Verkovic in 1860, Russians V. Grigorovich in 1848, V. Makushev and M.F. Mirkovitch in 1867, as well as Austrian K. Sax in 1878 published ethnography or linguistic books, or travel notes, which defined the Slavic population of Macedonia as Bulgarian. Austrian doctor J. Muller published travel notes in 1844 where he regarded the Slavic population of Macedonia as Serbian. The region was further identified as predominantly Greek by French F. Bianconi in 1877 and by Englishman E. Stanford in 1877. Stanford maintained that the urban population of Macedonia was entirely Greek, whereas the peasantry was of mixed, Bulgarian-Greek origin and had Greek consciousness but had not yet mastered the Greek language.

The predominant view of a Bulgarian character of the Slavs in Macedonia was reflected in the borders of future autonomous Bulgaria as drawn by the Constantinople Conference in 1876 and by the Treaty of San Stefano in 1878. Bulgaria according to the Constantinople Conference included present-day Vardar and Pirin Macedonia and excluded the predominantly “patriarchist” southern Macedonia. The Treaty of San Stefano, which reflected the maximum desired by Russian expansionist policy, gave Bulgaria the whole of Macedonia except Thessaloniki, the Chalcidice peninsula and the valley of the Aliákmon.

The Macedonian Question

The decision taken at the Congress of Berlin to leave Macedonia within the borders of the Ottoman Empire soon turned the region into the apple of discord between Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria. The ruthless propaganda war, the numerous outbursts of violence, and the inability of the Great powers to come up with a satisfactory solution earned the almost constant trouble in Macedonia the name “the Macedonian Question”. Unlike most disputed territories, Macedonia’s neighbouring countries contested not only the land but also the people, each regarding them as a subset of their own peoples.

Serbian Propaganda

19th century Serbian nationalism viewed Serbs as the people chosen to lead and unite all southern Slavs into one country, Yugoslavia (the country of the southern Slavs). According to some versions of this doctrine, Bulgarians were "Bulgarized Serbs", Croatians "Catholic Serbs", etc. Moderate Serbian scholars and political leaders before 1878, however, generally recognised Macedonia as Bulgarian land and directed their aspirations to Bosnia, Herzegovina and Kosovo.

The Congress of Berlin of 1878, which granted Bosnia and Herzegovina to Austria-Hungary, redirected Serbia’s ambitions to Macedonia and a propaganda campaign was launched at home and abroad to prove the Serbian character of the region. A great contribution to the Serbian cause was made by Croat astronomer and historian Spiridon Gopcevic (also known as Leo Brenner). Gopcevic published in 1889 the ethnographic research Macedonia and Old Serbia, which defined more than three-quarters of the Macedonian population as Serbian. The population of Kosovo and northern Albania was identified as Serbian or Albanian of Serbian origin and the Greeks along the Aliákmon as Greeks of Serbian origin.

The work of Gopcevic was further developed by two Serbian scholars, geographer Jovan Cvijic and linguist Aleksandar Belic. Less extreme than Gopcevic, Cvijic and Belic claimed only the Slavs of northern Macedonia were Serbian whereas those of southern Macedonia were identified as "Macedonian Slavs", an amorphous Slavic mass that was neither Bulgarian, nor Serbian but could turn out either Bulgarian or Serbian if the respective people were to rule the region. The only Slavs in Macedonia which were referred to as Bulgarian were those living along the Strymon and Nestos rivers, i.e. present-day Pirin Macedonia and parts of northeastern Greece. Cviic further argued that the name Bugari (Bulgarians) used by the Slavic population of Macedonia to refer to themselves actually meant only ‘rayah’ – peasant Christians – and in no case affiliations to the Bulgarian ethnicity.

The Serbian propaganda effort in Macedonia was led chiefly on the educational front. The number of Serbian schools in Macedonia and Kosovo rose from only a handful of before 1878 to 178 with 321 teachers and 7,200 pupils at the turn of the 20th century. The Society of Saint Sava in Belgrade gave study scholarships to talented Macedonians, usually turning them into staunch supporters of the Serbian cause after the end of their education. Serbia was also successful in launching armed guerilla groups, mainly in northern Macedonia, which clashed with pro-Bulgarian IMRO. Despite the enormous financial support from Serbia the Serbian cause in Macedonia never made a significant success outside the northern districts of Tetovo, Skopje and Kumanovo where the local dialect had certain similarities with Serbian.

Greek Propaganda

As it was firmly established by the end of the 19th century that the majority of the population of Macedonia was of Slavic origin, the arguments which Greece used to promote its cause were usually of historical but also of religious character. The Greeks consistently linked nationality to the allegiance to the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Terms like "Bulgarophone", "Albanophone" and "Vlachophone" Greeks were coined to describe the population of Slavic, Albanian and Aromanian origin which owed allegiance to the Patriarchate and had Greek schools.

Like the Serbian and Bulgarian propaganda efforts, the Greek one initially also concentrated on education. Greek schools in Macedonia at the turn of the 20th century totalled 927 with 1,397 teachers and 57,607 pupils. As from the 1890s Greece also started sending armed guerilla groups to Macedonia (see Greek Struggle for Macedonia) specially after the death of Pavlos Melas, which fought the detachments of IMRO, terrorised the "Exarchist" Bulgarian population and allegedly committed a massacre of some 60 peasants in the village of Zagorichani near Kastoria in 1905.

The Greek cause predominated in southern Macedonia where it was supported by the Greeks, by a substantial part of the Slavic population and by nearly all Aromanians. Support for the Greeks was much less pronounced in central Macedonia, coming from local Aromanians and only a fraction of the Slavs; in the northern parts of the region it was almost non-existent.

Bulgarian Propaganda

The independence of Bulgaria in 1878 had the same effect on the Bulgarian idea in Macedonia as the independence of Greece to the Hellenic one half a century earlier. The consequences were closure of schools, expelling of priests of the Bulgarian Exarchate and emigration of the majority of the young Macedonian intelligentsia. This first emigration triggered a constant trickle of Macedonian-born refugees and emigrants to Bulgaria. Their number stood at ca. 100,000 by 1912.

The Bulgarian idea made a remarkable comeback in the 1890’s with regard to both education and armed resistance. At the turn of the 20th century there were 785 Bulgarian schools in Macedonia with 1,250 teachers and 39,892 pupils. The Bulgarian Exarchate held jurisdiction over seven dioceses (Skopje, Debar, Ohrid, Bitola, Nevrokop, Veles and Strumica), i.e. the whole of Vardar and Pirin Macedonia and some of southern Macedonia. The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), which was founded in 1893 as the only guerilla organization established by locals, quickly developed a wide network of committees and agents turning into a "state within the state" in much of Macedonia. IMRO fought not only against the Ottoman authorities, but also against the pro-Serbian and pro-Greek parties in Macedonia, terrorising the population supporting them.

The failure of the Ilinden Uprising in 1903 signified a second weakening of the Bulgarian cause resulting in closure of schools and a new wave of emigration to Bulgaria. IMRO was also weakened and the number of Serbian and Greek guerilla groups in Macedonia substantially increased. The Exarchate lost the dioceses of Skopje and Debar to the Serbian Patriarchate in 1902 and 1910, respectively. Despite this, the Bulgarian cause preserved its dominant position in central and northern Macedonia and was also strong in southern Macedonia.

Slav Macedonian Propaganda

The Slav Macedonian idea during that period was at best at the inception stage. In 1880 Georgi Pulevski published in Sofia Slognica Rechovska, an attempt at a grammar of the dialect of Macedonia. The first significant manifestation of Slav Macedonian nationalism was the book On the Macedonian Matters (1904) by Krste Misirkov. In the book Misirkov advocated that the Slavs of Macedonia should take a separate way from the Bulgarians and the Bulgarian language. While arguing from a pro-Serbian point of view, Misirkov considered that the term "Macedonian" should be used to define the whole Slav population of Macedonia, obliterating the existing division between Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbians. The adoption of a separate Macedonian language was also advocated as a means of unification of the Macedonian Slavs with Serbian, Bulgarian and Greek consciousness. On the Macedonian Matters was written in the western (Bitola-Prilep) Macedonian dialect which was proposed by Misirkov as the basis for the future language (as the eastern dialect was too close to Bulgarian and the northern one too close to Serbian).

While Misirkov talked about the Macedonian consciousness and the Macedonian language as about a future goal, he described Macedonia of the early 20th century as inhabited by Bulgarians, Greeks, Serbs, Turks, Albanians, Aromanians, and Jews. As regards the Macedonians themselves, Misirkov claimed that they had called themselves Bulgarians until the publication of the book and were always called Bulgarians by independent observers until 1878 when the view of the Serbs also started to get recognition.

Misirkov rejected the ideas in On the Macedonian Matters later and turned into a staunch advocate of the Bulgarian cause - to return to the Slav Macedonian idea again in the 1920s. The ideas of Misirkov, Pulevski and other Macedonian Slavs remained largely unnoticed until the 1940s when they were adopted by the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and influenced the codification of the Macedonian language.

Claims of present-day historians from the Republic of Macedonia that the "Autonomists" in IMRO defended a Slav Macedonian position are largely ungrounded as IMRO regarded itself and was regarded - by the Ottoman authorities, the Greek guerilla groups, the contemporary press in Europe and even by Misirkov - as an exclusively Bulgarian organization.

Romanian Propaganda

Attempts at a Romanian propaganda among the Aromanian population of Macedonia began as early as 1855. The first Romanian school was, however, established as late as 1886. The total number of schools grew to ca. 40 at the beginning of the 20th century. Though the Romanian propaganda made some success in Bitola, Krushevo, the Aromanian villages in the districts of Bitola and Ohrid and even among some Slavs, the majority of the Macedonian Aromanians remained advocates of Hellenism.

Independent Point of View

Independent sources in Europe between 1878 and 1918 generally tended to view the Slavic population of Macedonia in two ways: as Bulgarians and as Macedonian Slavs.

German scholar Gustav Weigand was one of the most prominent representatives of the first trend with the books Ethnography of Macedonia (1924, written 1919) and partially with The Aromanians (1905). The author described all ethnic groups living in Macedonia, showed empirically the close connection between the western Bulgarian dialects and the Macedonian dialects and defined the latter as Bulgarian. The International Commission constituted by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 1913 to inquire into causes and conduct of the Balkan Wars also talked about the Slavs of Macedonia as about Bulgarians in its report published in 1914. The Commission had eight members from Great Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia and the United States.

The term "Macedonian Slavs" was used by scholars and publicists in three general meanings:

- as a politically convenient term to define the Slavs of Macedonia without offending Serbian and Bulgarian nationalism;

- as a distinct group of Slavs different from both Serbs and Bulgarians, yet closer to the Bulgarians and having predominantly Bulgarian ethnical and political affinities;

- as a distinct group of Slavs different from both Serbs and Bulgarians having no developed national consciousness and no fast ethnical and political affinities (the definition of Cvijic).

An instance of the use of the first meaning of the term was, for example, the ethnographic map of the Slavic peoples published in (1890) by Russian scholar Zarjanko, which identified the Slavs of Macedonia as Bulgarians. Following an official protest from Serbia the map was later reprinted identifying them under the politically correct name "Macedonian Slavs".

The term was used in a completely different sense by British journalist Henry Brailsford in Macedonia, its races and their future (1906). The book contains Brailford's impressions from a five-month stay in Macedonia shortly after the suppression of the Ilinden Uprising and represents an ethnographic report. Brailford defines the dialect of Macedonia as neither Serbian, nor Bulgarian, yet closer to the second one. An opinion is delivered that any Slavic nation could "win" Macedonia if it is to use the needed tact and resources, yet it is claimed that the Bulgarians have already done that. Brailsford uses synonymously the terms "Macedonian Slavs" and "Bulgarians", the "Slavic language" and the "Bulgarian language". The chapter on the Macedonians Slavs/the Bulgarians is titled the "Bulgarian movement", the IMRO activists are called "bulgarophile Macedonians".

The third use of the term can be noted among scholars from the allied countries (above all France and the United Kingdom) after 1915 and is roughly equal to the definition given by Cvijic (see above).

Development of the Name "Macedonian Slavs"

The name "Macedonian Slavs" started to appear in publications at the end of the 1880s and the beginning of the 1890s. Though the successes of the Serbian propaganda effort had proved that the Slavic population of Macedonia was not only Bulgarian, they still failed to convince that this population was, in its turn, Serbian. Rarely used until the end of the 19th century compared to ‘Bulgarians’, the name ‘Macedonian Slavs’ served more to conceal rather than define the national character of the population of Macedonia. Scholars resorted to it usually as a result of Serbian pressure or used it as a general name for the Slavs inhabiting Macedonia regardless of their ethnic affinities.

However, by the beginning of the 20th century, the continued Serbian propaganda effort and especially the work of Cvijic had managed to firmly entrench the concept of the Macedonian Slavs in European public opinion and the name was used almost as frequently as ‘Bulgarians’. Even pro-Bulgarian researchers such as H. Brailsford and N. Forbes argued that the Macedonian Slavs differed from both Bulgarians and Serbs. Practically all scholars before 1915, however, including strongly pro-Serbian ones such as R.W. Seton-Watson, admitted that the affinities of the majority of them lied with the Bulgarian cause and the Bulgarians and classified them as such.

Bulgaria's entry into World War I on the side of the Central Powers signified a dramatic shift in the way European public opinion viewed the Slavic population of Macedonia. For the Central Powers the Slavs of Macedonia became nothing but Bulgarians, whereas for the Allies they turned into anything else but Bulgarians. The ultimate victory of the Allies in 1918 led to the victory of the vision of the Slavic population of Macedonia as of Macedonian Slavs, an amorphous Slavic mass without a developed national consciousness.

The "Missing" National Consciousness

What stood behind the difficulties to properly define the nationality of the Slavic population of Macedonia was the apparent levity with which this population regarded it. Nationality in early 20th century Macedonia was a matter of political convictions and financial benefits, of what was considered politically correct at the specific time and of which armed guerilla group happened to visit the respondent's home last. The process of Hellenization at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century affected only a limited stratum of the population, the Bulgarian Revival in the middle of the 19th century was too short to form a solid Bulgarian consciousness, the financial benefits given by the Serbian propaganda were too tempting to be declined. It was not a rare occurrence for whole villages to switch their nationality from Greek to Bulgarian and then to Serbian within a few years or to be Bulgarian in the presence of a Bulgarian commercial agent and Serbian in the presence of a Serbian consul. On several occasions peasants were reported to have answered in the affirmative when asked if they were Bulgarians and again in the affirmative when asked if they were Serbs. Though this certainly cannot be valid for the whole population, many Russian and Western diplomats and travellers defined Macedonians as lacking a "proper" national consciousness.

Statistical data

The 1911 edition of the Encylopaedia Britannica gave the following statistical estimates about the population of Macedonia:

- Bulgarians (described in encyclopaedia as "Slavs, the bulk of which is regarded by almost all independent sources as Bulgarians", a statement referring to the controversy between Bulgaria and Serbia as to the national affinities of the Slavs of Macedonia): ca. 1,150,000, whereof, 1,000,000 Orthodox and 150,000 Muslims (the so-called Pomaks)

- Turks: ca. 500,000 (Muslims)

- Greeks: ca. 250,000, whereof ca. 240,000 Orthodox and 14,000 Muslims

- Albanians: ca. 120,000, whereof 10,000 Orthodox and 110,000 Muslims

- Vlachs: ca. 90,000 Orthodox and 3,000 Muslims

- Jews: ca. 75,000

- Roma: ca. 50,000, whereof 35,000 Orthodox and 15,000 Muslims

In total 1,300,000 Christians (almost exclusively Orthodox), 800,000 Muslims, 75,000 Jews, a total population of ca. 2,200,000 for the whole of Macedonia.

It needs to be taken into account that a substantial part of the Bulgarian population in southern Macedonia regarded itself as Greek and a smaller percentage, mostly in northern Macedonia, as Serbian. All Muslims (except the Albanians) tended to view themselves and were viewed as Turks, irrespective of their mother tongue. Most Vlachs and orthodox Albanians regarded themselves as Greeks.

The Ottoman Empire did not hold any census based on self-determination but used statistics based on birth records. As these were consistently falsified to present the bulk of the population of Macedonia as Muslim, they cannot be regarded as reliable statistical data.

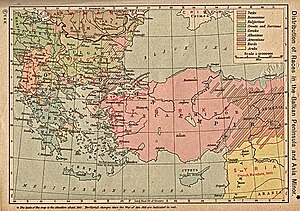

Modern Times

The Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and World War I (1914-1918) left Macedonia divided between Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Albania and resulted in significant changes in its ethnic composition.

Greece

Bulgarian and other non-Greek schools in southern (Aegean) Macedonia were closed and Bulgarian teachers and priests were deported as early as the First Balkan War. The bulk of the Slavic population of southeastern Macedonia fled to Bulgaria during the Second Balkan War or was resettled there in the 1920’s by virtue of a population exchange agreement. The Slavs in southwestern Macedonia, who were referred to by the Greek authorities as “Slavomacedonians”, “Slavophone Greeks” and “Bulgarisants”, were subjected to a gradual assimilation by the Greek majority. Their numbers were reduced by a large-scale emigration to North America in the 1920s and the 1930s and to Eastern Europe and Yugoslavia following the Greek Civil War (1944-1949).

The 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey led to a radical change in the ethnic composition of Greek Macedonia. Some 350,000 Turks and other Muslims left the region and were replaced by 500,000 Greeks and other Christians from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace.

Greece came under the control of the Nazi-led Axis during World War II. By the beginning of 1941 the whole of Greece was under a tripartite German, Italian and Bulgarian occupation. The Bulgarians were permitted to occupy western Thrace and parts of Macedonia where they settled Bulgarian migrants (including former Bulgarian refugees from these regions) and persecuted the Greek population.

The present number of the Slavic speakers in Greece has been subject to much speculation with numbers varying between 10,000 and 240,000. As Greece does not hold census based on self-determination and mother tongue, no official data is available. However, it is generally assumed that the lower number (10,000) represents the number of actual speakers, whereas the higher one (240,000) defines Greek citizens of Slavic origin. For more information about the region and its population see Greek Macedonia.

Serbia and Yugoslavia

After the Balkan Wars (1913-1914) the Slavs in Serbian (Vardar) Macedonia were regarded as southern Serbs and the language they spoke a southern Serbian dialect. The Bulgarian, Greek and Romanian schools were closed, the Bulgarian priests and all non-Serbian teachers were expelled. Bulgarian surname endings '-ov/-ev' were replaced with the typically Serbian ending '-ich' and the population which considered itself Bulgarian was heavily persecuted. The policy of Serbianization in the 1920s and 1930s clashed with popular pro-Bulgarian sentiment stirred by IMRO detachments infiltrating from Bulgaria, whereas local communists favoured the path of self-determination suggested by the Yugoslav Communist Party in the 1924 May Manifesto.

Bulgarian troops were welcomed as liberators in 1941 but mistakes of the Bulgarian administration made a growing number of people resent their presence by 1944. The region received the status of a constituent republic within Yugoslavia and in 1945 a separate, Macedonian language was codified. The population was declared Macedonian, a nationality different from both Serbs and Bulgarians. The decision was politically motivated and aimed at weakening the position of Serbia within Yugoslavia and of Bulgaria with regard to Yugoslavia. Surnames were again changed to include the ending '-ski', which was to emphasise the unique nature of the Slav Macedonian population.

It may be only a matter of speculation whether the Macedonian Slavs of present-day Republic of Macedonia would have developed as a separate ethnic group had Macedonia been incorporated into a “Great Bulgarian” state in 1878 or 1913. The influence of the Serbian propaganda effort between 1881 and 1912 and the policy of intense Serbization in the interwar years, however, indisputably played a key role for severing of the ties of the Macedonian Slavs with the Bulgarians. Since 1945, the Macedonian Slavs of the Republic of Macedonia have demonstrated without any exception a strong and even aggressive at times Macedonian consciousness. Any ties with the Bulgarians have been denounced and the Bulgarian affinities of their national heroes from the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century have been fiercely denied, even in the face of fact. The quick success of the Slav Macedonian idea in the 1940s and the tenacity with which the Macedonian Slavs have held on to it throughout the second half of the 20th century indicates that the process of formation of Slav Macedonian consciousness had been well under way before World War II (contrary to Bulgarian and Greek claims, for more information see Macedonian language and Macedonia), to finally crystallize under the oppressive and ineffective Bulgarian administration between 1941 and 1944. For more current information about the population of Republic of Macedonia see Demographics of the Republic of Macedonia.

Bulgaria

The Slavic population in Pirin Macedonia remained Bulgarian after 1913. IMRO was a “state within the state” in the region in the 1920’s using it to launch attacks in the Serbian part of Macedonia. By that time IMRO had become a right-wing Bulgarian ultranationalist organization. In 1946 the population of Pirin Macedonia was declared Slav Macedonian, in anticipation of the future incorporation of the region into the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and of the admission of Bulgaria into the Yugoslav Federation. The policy change was orchestrated by the Soviet Union and followed the official line of the Comintern on the Macedonian question. At the end of the 1950’s the Communist party repealed its previous decision and adopted a position denying the existence of a “Macedonian” nation. The inconsistent Bulgarian policy has thrown most independent observers ever since into a state of confusion as to the real origin of the population in Bulgarian Macedonia.

After a brief upsurge of Slav Macedonian nationalism at the beginning of the 1990’s, sometimes resulting in clashes between nationalist IMRO and Slav Macedonian separatist organization UMO Ilinden, the commotion has largely subsided in recent time and the Slav Macedonian idea has become strongly marginalized. A total of 3,100 people in the Blagoevgrad District declared themselves Macedonian in the 2001 census (0,9% of the population of the region).

Albania

The Slavic minority in Albania is concentrated in two regions, Mala Prespa northeast of Korçë, eastern Albania, and Golo Bardo south of the western Macedonian town of Debar. Albania has recognised a 5,000 strong Macedonian Slav minority in Mala Prespa. In Golo Bardo there are both a Bulgarian and a Macedonian organization. Each of them claims that the local Slavic population is Bulgarian/Macedonian. The population itself, which is predominantly Muslim, has, however, preferred to call itself Albanian in official censuses.

References

References

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Edition 1911

- Banac, Ivo. (1984). The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics. Cornell

University Press: Ithaca/London

- Jezernik, Bozhidar. Macedonians: Conspicuous By Their Absence

- Boué, Ami. (1840). Le Turquie d’Europe. Paris: Arthus Bertrand.

- Brailsford, Henry Noel. (1906). Macedonia: Its Races and Their Future. London: Methuen & Co

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (1914). Report of the International Commission To Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars. Washington: The Carnegie Endowment.

- Gopčević, Spiridon. (1889). Makedonien und Alt-Serbien. Wien: L. W. Seidel & Sohn.

- Misirkov, Krste P. (1903). Za makedonckite raboti. Sofia: Liberalni klub. (In Macedonian)

- Kunčov, Vasil. (1900). Makedonija. Etnografija i statistika. Sofia: Državna peиatnica.

- Lange-Akhund, Nadine. (1998). The Macedonian Question, 1893-1908 from Western Sources. Boulder, Colo. : New York.

- MacKenzie, Georgena Muir and Irby, I.P. (1971). Travels in the Slavonic Provinces of Turkey in Europe. New York, Arno Press.

- Poulton, Hugh. (1995). Who are the Macedonians? C.Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., London

- Roudometoff, Victor. (2000). The Macedonian Question: Culture, Historiography, Politics. Boulder, CO: East European Monographs.

- Weigand, Gustav. (1924). ETHNOGRAPHIE VON MAKEDONIEN, Geschichtlich-nationaler, spraechlich-statistischer Teil von Prof. Dr. Gustav Weigand, Leipzig, Friedrich Brandstetter.

- Wilkinson, H.R. (1951). Maps and Politics; a review of the ethnographic cartography of Macedonia, Liverpool University Press.

- Kuhn's Zeitschrift fόr vergleichende Sprachforschung XXII (1874), Gottingen:Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht