This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Tiamut (talk | contribs) at 14:46, 13 February 2008 (changing from sub-sub-sub heading to sub-heading to reflect the other usage of the term "Palestinian archaeology"). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:46, 13 February 2008 by Tiamut (talk | contribs) (changing from sub-sub-sub heading to sub-heading to reflect the other usage of the term "Palestinian archaeology")(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| It has been suggested that this article be merged into Biblical archaeology. (Discuss) Proposed since February 2008. |

Syro-Palestinian archaeology is a term used to refer to archaeological research conducted in the southern Levant. Palestinian archaeology is also commonly used in its stead when the area of inquiry centers on ancient Palestine. Besides its importance to the discipline of biblical archaeology, the region of ancient Palestine is one of the most important to an understanding of the history of the earliest peoples of the Stone Age.

While both biblical archaeology and Syro-Palestinian archaeology have tended to deal with the same region of study, the focus and approach adopted by each of these interrelated disciplines differs. Even those scholars who have continued to advocate a role for biblical archaeology have accepted the existence of a general branch of Palestinian archaeology or Syro-Palestinian archaeology. It should be noted that though the latter term is commonly employed by archaeologists in the southern Levant, it is rarely used by specialists in Syria itself.

Palestine's geographical location on the land bridge connecting Asia and Africa and its proximity to the "cradle of humankind" in Africa and the ancient civilizations of the Near East has played a key role in determining the prehistory and history of social change in the region dating back over one million years. Palestinian archaeology is however marked a degree of acrimony not shared in other area studies in the field. Archaeologists who consider Biblical scriptures to be legitimate historical documents have been attacked by mainstream scientific archaeologists who see the hard data from excavations as being incompatible with the Biblical "historical" record. The dispute led to a definitive split between biblical archaeologists and Syro-Palestinian archaeologists in the 1970s, and continues to rage within the field of Palestinian archaeology today.

Since the 1990s, the term Palestinian archaeology has also been used to refer to archaeological studies of the region conducted by Palestinians, largely centered around the Palestinian Institute of Archaeology at Bir Zeit University in the West Bank.

Origins

See also: Biblical archaeologyModern Palestinian archaeology began to be practiced in the late nineteenth century. Early expeditions lacked standardized methods for excavation and interpretation, and were often little more than treasure-hunting expeditions. A lack of awareness and attention to the importance of stratigraphy to the dating of objects, led to the digging of long trenches through the middle a site that made follow-up work by later archaeologists more difficult.

One early school of modern Palestinian archaeology revolved around the powerful and authoritative figure of William F. Albright (1891-1971). His scholarship and that of the Albright school, which tended to lean toward a favouring of biblical narratives, were treated with great deference during his lifetime. Albright himself held that Frederick Jones Bliss (1857-1939) was the Father of Palestinian archaeology; however, the work of Bliss is not well-known to those in the field. Jeffrey A. Blakely attributes this to the actions of Bliss' successor at the Palestine Exploration Fund, R.A.S. Macalister (1870-1950), who seems to have buried his predeccessor's achievements.

While the importance of stratigraphy, typology and balk to the scientific study of sites became the norm sometime in the mid-twentieth century, the continued tendency to ignore hard data in favour of subjective interpretations invited criticism. Paul W. Lapp, for example, whom many thought would take up the mantle of Albright before his premature death in 1970, engaged in a harsh critique of the field that same year, writing:

"Too much of Palestinian archaeology is an inflated fabrication Too often a subjective interpretation, not based on empirical stratigraphic observation, is used to demonstrate the validity of another subjective interpretation. We assign close dates to a group of pots on subjective typological grounds and go on to cite our opinion as independent evidence for similarly dating a parallel group. Too much of Palestinian archaeology's foundation building has involved chasing ad hominenem arguments around in a circle."

In 1974, William Dever established the secular, non-biblical school of Syro-Palestinian archaeology and mounted a series of attacks on the very definition of biblical archaeology. Dever argued that the name of such inquiry should be changed to an "archaeology of the Bible" or "archaeology of the Biblical period" to delineate the narrow temporal focus of Biblical archaeologists. Frank Moore Cross, who had studied under Albright and had taught Dever, took issue with Dever's critiques of the discipline of biblical archaeology. He emphasized that in Albright's view biblical archaeology was not synonymous with Palestinian archaeology, but rather that, "William Foxwell Albright regarded Palestinian archaeology or Syro-Palestinian archaeology as a small, if important section of biblical archaeology. One finds it ironical that recent students suppose them interchangeable terms." Dever responded to the criticism by agreeing that the terms were not interchangeable, but differed as to their relationship with one another, writing: "'Syro-Palestinian archaeology' is not the same as the 'biblical archaeology'. I regret to say that all who would defend Albright and 'biblical archaeology' on this ground, are sadly out of touch with reality in the field of archaeology."

Towards the end of the twentieth century, Palestinian archaeology became a more interdisciplinary practice. Specialists in archaeozoology, archaeobotany, geology, anthropology and epigraphy now work together to produce vast amounts of essential environmental and non-environmental data in mutlidisciplinary projects.

Foci in Syro-Palestinian archaeology

Ceramics analysis

See also: History of pottery in the Southern Levant See also: Palestinian potteryA central concern of Syro-Palestinian archaeology since its genesis has been the study of ceramics. Whole pots and richly decorated pottery are uncommon in the Levant and the plainer, less ornate ceramic artifacts of the region have served the analytical goals of archaeologists, much more than those of museum collectors. The ubiquity of pottery shards and their long history of use in the region makes ceramics analysis a particularly useful sub-discipline of Syro-Palestinian archaeology, used to address issues of terminology and periodization. Awareness of the value of pottery gained early recognition in a landmark survey conducted by Edward Robinson and Eli Smith, whose findings were published in first two works on the subject: Biblical Researches in Palestine (1841) and Later Biblical Researches (1851).

Ceramics analysis in Syro-Palestinian archaeology has suffered from insularity and conservatism, due to the legacy of what J.P Hessel and Alexander H. Joffe call "the imperial hubris of pan-optic 'Biblical Archaeology.'" The dominance of biblical archaeological approaches in the early twentieth century meant that the sub-discipline was partitioned off from other branches of ancient Near Eastern studies, with the exception of selected questions of Northwest Semitic epigraphy and Assyriology that were related to the biblically-oriented studies.

As a result, widely varying sets of principles, emphases, and definitions are used to determine local typologies among the different archaeologists working in the region. Attempts to identify and bridge the gaps made some headway at the Durham conference, though there was recognition that agreement on a single method of ceramic analysis or a single definition of a type may not be possible. The solution proposed by Hessel and Joffe is for all archaeologists in the field to provide more explicit descriptions of the objects of they study. The more information provided and shared between those in the related sub-disciplines, the more likely it is that they will be able to identify and understand where the commonalities in the different typlogical systems employed lie.

Defining Phoenician

Syro-Palestinian archaeology also includes the study of Phoenician culture, cosmopolitan in character and widespread in its distribution in the region. According to Benjamin Sass and Christoph Uehlinger, the questions of what is actually Phoenician and what is specifically Phoenician, in Phoenician iconography, constitute one well-known crux of Syro-Palestinian archaeology. Without answers to these questions, the authors contend that research exploring the degree to which Phoenician art and symbolism penetrated into the different areas of Syria and Palestine will make little progress.

Practitioners

American and Israeli

Main article: Archaeology of IsraelBy the 1970s, Israeli archaeologists had begun to make significant contributions to the field of the archaeology of Syro-Palestinian archaeology within their own territory. Along with archaeologists from the United States of America, the two nations contribute the largest group of archaeologists working in the field in Israel. Joint archaeological missions between Americans and Jordanians have also been conducted. Of these, Nicolo Marchetti, an Italian archaeologist, has commented on the lack of real collaboration, stating, " you might find, at a site, one hole with Jordanians and 20 holes with Americans digging in them. After the work, usually it's the Americans who explain to the Jordanians what they've found."

British and European

British and European archaeologists also continue to excavate and research in the region, with many of these projects centered in Arab countries, primary among them Jordan and Syria, and to a lesser extent in Lebanon. The most significant British excavations include the Tell Nebi Mend site (Qadesh) in Syria and the Tell Iktanu and Tell es-Sa'adiyah sites in Jordan. Other notable European projects include Italian excavations at Tell Mardikh (Ebla) and Tell Meskene (Emar) in Syria, French participation in Ras Shamra (Ugarit) in Syria, French excavations at Tell Yarmut and German excavations at Tell Masos (both in Israel) and Dutch excavations Tell Deir 'Alla in Jordan.

Italian archaeologists were the first to undertake joint missions with Palestinian archaeologists in the West Bank, which were only possible after the signing of the Oslo Accords. The joint project was conducted in Jericho and coordinated by Hamadan Taha, director of the Palestinian Antiquities Department and the University of Rome "La Sapienza", represented by Paolo Matthiae, the same archeologist who discovered the site of Ebla in 1964. Unlike the joint missions between Americans and Jordanians, this project involved Italians and Palestinians digging at the same holes, side by side.

Arab

After the creation of independent Arab states in the region, national schools of archaeology were established in 1960s. The research focus and perspective differs from that of Western archaeological approaches, tending to avoid both biblical studies and its connections to modern and ancient Israel, as well as its connections to the search for Western cultural and theological roots in the Holy Land. Concentrating on their own perspectives which are generally, though not exclusively oriented toward Islamic archaeology, Arab archaeologists have added a "vigorous new element to Syro-Palestinian archeology."

Palestinian archaeology condcuted by Palestinian practitioners

The involvement of the Palestinian people as practitioners in the study of Palestinian archaeology is relatively recent. The Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land notes that, "The 1990s have seen the development of Palestinian archaeological activities, with a focus on tell archaeology on the one hand (H. Taha and M. Sadeq) and on the investigation of the indigenous landscape and cultural heritage on the other (K. Nashef and M. Abu Khalaf)."

The Palestinian Archaeology Institute at Bir Zeit University in Ramallah was established in 1987 with the help of Albert Glock, who headed the archaeology department at the University at the time. Glock's objective was to establish an archaeological program that would emphsize the Palestinian presence in Palestine, writing that, "Archaeology, as everything else, is politics, and my politics of the losers." In 1992, the 67-year-old Glock was killed in the West Bank by unidentified gunmen. In 1993, the first archaeological site to be excavated by researchers from Bir Zeit Univeristy was undertaken in Tell Jenin.

Khaled Nashef, a Palestinian archaeologist at Bir Zeit and the editor of the University's Journal of Palestinian Archaeology echoed Glock's view, arguing that for too long, the history of Palestine has been written by Christian and Israeli "biblical archaeologists", and that Palestinians must themselves re-write that history, by beginning with the archaeological recovery of ancient Palestine.

Hamdan Taha, the director of the Palestinian National Authority's Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage is responsible for overseeing preservation and excavation projects that involve both internationals and Palestinians. Gerrit van der Kooij, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands who works with Taha has defended him from anonymous outside criticism, stating, "It doesn't surprise me that outsiders become frustrated sticks by his policy of equal partnership. That means Palestinians must be involved at every step," from planning and digging to publishing. In Van der Kooij's opinion, this policy is "fully justified and adds more social value to the project."

Dever submits that the recent insistence that Palestinian archaeology and history be written by "real Palestinians" stems from the influence of those he terms the "biblical revisionists", such as Keith W. Whitelam, Thomas L. Thompson, Phillip Davies and Niels Peter Lemche. Whitelam's book, The Invention of Ancient Israel: The Silencing of Palestinian History (1996) and Thompson's book, The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology and the Myth of Israel (1999) were both translated into Arabic shortly after their publication. Dever speculates that, "Nashef and many other Palestinian political activists have obviously read it." He is harshly critical of both books, describing Whitelam's thesis that Israelis and "Jewish-inspired Christians" invented Israel, thus deliberately robbing Palestinians of their history, as "extremely inflammatory" and "bordering on anti-Semitism." Thompson's book is decribed by him to be "even more rabid."

Dever cites an editorial by Nashef published in the Journal of Palestinian Archaeology in July of 2000 entitled, "The Debate on 'Ancient Israel': A Palestinian Perspective," which explicitly names the four "biblical revisionists" mentioned above as evidence for his claim that their "rhetoric" has influenced Palestinian archaeologists. In the editorial itself, Nashef writes: "The fact of the matter is, the Palestinians have something completely different to offer in the debate on 'ancient Israel,' which seems to threaten the ideological basis of BAR (the American popular magazine, Biblical Archaeology Review, which turned down this piece - WGD): they simply exist, and they have always existed on the soil of Palestine ..."

Challenges posed by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Damage to archaeological sites

Construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier has damaged and threatens to damage a number of sites of interest to Palestinian archaeology in and around the Green Line, prompting condemnation from the World Archaeological Congress (WAC) and a call for Israel to abide by UNESCO conventions that protect cultural heritage. In the autumn of 2003, bulldozers preparing the ground for a section of the barrier that runs through Abu Dis in East Jerusalem damaged the remains of a 1,500-year-old Byzantine era monastery. Construction was halted to allow the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) to conduct a salvage excavation that recovered a mosaic, among other artifacts. Media reported that an IAA official media blamed the IDF for proceeding without procuring the opinion of the IAA.

Another site potentially threatened by the projected path of the separation barrier is that of Gibeon in the West Bank. The focus of an Israeli-American-Palestinian initiative funded by a $400,000 USD grant from the State Department to protect heritage sites, there will be almost certain damage to the site if the barrier's construction proceeds as forecasted. Gibeon is slated to be separated from the nearby Palestinian village of Al-Jib which relies on restoration and excavation projects in the area for employment opportunities. According to Adel Yahyeh, a Palestinian archaeologist, the IAA is aware of the threat and is sympathetic but may lack jurisdiction to enforce protections.

Contestation over the ownership of artifacts

Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls, a series of 800 scrolls written in Aramaic, Greek and Hebrew that were discovered in 11 caves in the hills above Qumran between 1947 and 1956 are the subject of an ownership debate between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. Israel purchased some of the parchments, believed to have been composed or transcribed between 1 BCE and 1 ACE, after they were first unearthed by a Bedouin shepherd. The remainder were seized by Israel from the Rockefeller Museum after the occupation of East Jerusalem in the wake of the 1967 war. When 350 participants from 25 countries gathered at the Israel Museum to hear a series of lectures on the fiftieth anniversary of their discovery, Amir Drori, head of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), announced that the Jewish state would keep the 2,000-year-old documents as they were legally inherited and an inseparable part of Jewish tradition. His Palestinian counterpart, Hamdan Taha, responded that Israel's capture of the works after the 1967 war was theft "which should be recitified now". The issue of ownership over the Scrolls was to form part of 'final status' talks envisioned in the Oslo Accords seeking an overall settlement to Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Gaza artifacts

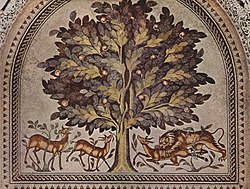

In 1974, the IAA removed a sixth century Byzantine mosaic from Gaza City, dubbed 'King David Playing the Lyre', which now decorates the synagogue section of the Israel Museum. According to Jerusalem Post, under international law, it is illegal for an occupying power to remove ancient artifacts from the land it occupies. Israel has countered that Palestinians have been unable to safeguard ancient sites in Areas A and B of the West Bank from looting. Hananya Hizmi, deputy of Israel's Department of Antiquities in Judea and Samaria, explained, "Probably it was done to preserve the mosaic. Maybe there was an intention to return and it didn't work out. I don't know why." In the lead up to Israel's unilateral disengagement from the Gaza Strip, Dr. Moain Sadeq, director general of the Department of Antiquities in Gaza, expressed Palestinian fears that Israel would once again confiscate artifacts, this time from a sixth century Byzantine church discovered in 1999 by an Israeli archaeologist on the site of a military installation in the northwestern tip of the Gaza Strip. The well-preserved 1,461-year-old church contains three large and colorful mosaics with floral-motifs and geometric shapes with a nearby Byzantine hot bath and artificial fishponds. Hizmi said that, "No decision has been taken yet to remove the mosaic," but that the mosaics would be removed to prevent damage, if necessary."

See also

External links

References

- On page 16 of his book, Rast notes that the term Palestine is commonly used by archaeologists in Jordan and Israel to refer to the region encompassed by modern-day Israel, Jordan and the West Bank.

- Rast, 1992, p. xi.

- ^ Davis, 2004, p. 146.

- Akkermans and Schwartz, 2003, p. 2.

- ^ Levy, 1998, p. 5.

- ^ Henry, 2003, p. 143.

- ^ Rast, 1992, pp. 1-2.

- J.A. Blakely (1993). "Frederick Jones Bliss: Father of Palestinian Archaeology". The Biblical Archaeologist. Vol. 56, No. 3. American Schools of Oriental Research: 110–115. ISSN 0006-0895.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Moorey, 1992, p. 131.

- Davis, 2004, p. 147.

- Rast, 1992, p. 3.

- ^ Philip and Baird, 2000, p. 31.

- Millard, 1997, p. 23.

- Philip and Baird, 2000, p. 36.

- Philip and Baird, 2000, p. 45.

- Sass and Uehlinger, 1993, p. 267.

- ^ Barton, 2002, pp. 359-361.

- ^ Manuela Evangelista. "The Secrets Come Tumblin' Down". Galileo: Diary of Science and Global Issues.

- Negev and Gibson, 2001, p. 49.

- "The mysterious death of Dr. Glock". The Guardian. 2 June 2001. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Suzanne MacNeille (November 11 2001). "Books in Brief: Nonfiction - Sacred Geography: A Tale of Murder and Archeology". Retrieved 2008-02-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Ademar Ezzughayyar, Muhammad Al-Zawahra, Hamed Salem (5 January 1996). "Molluscan Fauna from Site 4 of Tell Jenin (Northern West Bank—Palestine)". Journal of Archaeological Science. Volume 23, Issue 1: pp. 1-6.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dever, 2003, p. 240.

- John Bohannon (21 April 2006). "Palestinian Archaeology Braces for a Storm". Science. Vol. 312, no. 5772: pp. 352-353.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "WAC vs. the Wall". Archaeology: A Publication of the Archaeological Institute of America. Volume 57, Number 2. March–April 2004. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Christopher Walker (July 1997). "Scholars dispute ownership of Dead Sea Scrolls". The Times. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ Orly Halpern. . Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)

Bibliography

- Akkermans, Peter M.M.G. and Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521796660

- Barton, John (2002). The Biblical World. Routledge. ISBN 0415161053

- Davis, Thomas W (2004). Shifting Sands: The Rise and Fall of Biblical Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195167104

- Dever, William (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0802809758

- Henry, Roger (2003). Synchronized Chronology: Rethinking Middle East Antiquity. Algora Publishing. ISBN 0875861857

- Levy, Thomas Evan (1998). Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0826469965

- Millard, Ralph (1997). Discoveries from Bible Times: Archaeological Treasures Throw Light on the Bible. Lion. ISBN 0745937403

- Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1992). A Century of Biblical Archaeology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 066425392X

- Negev, Avraham and Shimon Gibson (2001). Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0826485715

- Philip, Graham and Douglas Baird (2000). Ceramics and Change in the Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1841271357

- Rast, Walter E (1992). Through the Ages in Palestinian Archaeology: An Introductory Handbook. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1563380552

- Sass, Benjamin and Christoph Uehlinger (1993). Studies in the Iconography of Northwest Semitic Inscribed Seals. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3525537603