This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Mike Babic (talk | contribs) at 21:46, 13 March 2008 (to use the term vlah to describe serbs is pejorative in modern times. thus, i will need to see some evidence that this term was used to describe the serbs at that time as you claim). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:46, 13 March 2008 by Mike Babic (talk | contribs) (to use the term vlah to describe serbs is pejorative in modern times. thus, i will need to see some evidence that this term was used to describe the serbs at that time as you claim)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Part of a series on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

| Native |

DiasporaEurope

Overseas |

| Culture |

| History |

| Language |

| Religion |

| Related nations |

The Serbs of Croatia are the largest national minority in Croatia today since they currently comprise around 4.5% of Croatia's total population. According to the 2001 Croatian population census there were 201,631 Serbs. The modern estimates, however, record a significant drop in the population, mainly due to negative increase, estimating to be around 180,000 people. The total population of Serbs who originate directly from Croatia is estimated at around 700,000 people. Due to various reasons, mainly the mass-flight during Operation Storm, only a fraction of Croatian Serbs actually still live in their native homeland of Croatia. The Croatian electoral commission recorded on the 2007 minority national councils elections 274,968 eligible Croatian voters of Serb ethnicity, but mainly of foreign residence.

Population

The number of Serbs in Croatia was much larger in 1991, when they numbered at least 581,663 and over 12,2% of the total population of Croatia. The largest exactly recorded number of Serbs in a census was in 1971 when there were 626,789 Serbs in SR Croatia (over 14% of the total at the time). During World War II, Serbs comprised 30% of the population of the Independent State of Croatia (1941-1945) and lived on one half of its soil, but that territory also included all of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The 1931 census in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia recorded around 633,000. The 1840 Austrian population census conducted in Croatia and Slavonia, 504,179 Serbs were registered, which formed 32% of Croatia's population . The loss of the heavily Serb populated Eastern Srijem region, the incorporation of Istria region into the People's Republic of Croatia, and the non-inclusion of Croat dominated regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina into the People's Republic of Croatia, as had been done in the Banovina of Croatia are examples of territorial changes that either increased or reduced the relative percentage of the Croatian population that was Serb.

The large decrease in the number of Serbs in Croatia was caused by the Yugoslav wars, more specifically the 1991-1995 Croatian war of Independence. The majority of the population continues to live in exile. The largest places are Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro, where the estimates range from 150,000 to 400,000.

| State | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Croatia | 158,365 | 2.5% |

| Serbia and Montenegro | 150,000-200,000 | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 150,000 | |

| Elsewhere in the world | 100,000 | |

| Total | 600,000-750,000 |

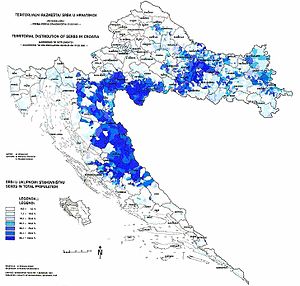

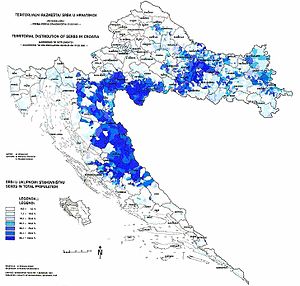

Geographical representation

Most Croatian Serbs are/were concentrated in regions of Banija, Kordun, Lika, Northern Dalmatia, Western and Eastern Slavonia, Srem and Baranja. Smaller groups of Serbs can be also found elsewhere in Slavonia and Dalmatia, Bilogora, Moslavina, Gorski kotar and Istria. Serbs can be also found in all major cities in Croatia; the largest concentration of Serbs in Croatia is probably in Zagreb.

In 2001 there were four counties where the Serbs numbered over 10% of the population: Vukovar-Srijem county, Sisak-Moslavina county, Karlovac county and Lika-Senj county. There were 16 municipalities with a Serb majority:

- Dvor and Gvozd in Sisak-Moslavina county;

- Krnjak in Karlovac county;

- Donji Lapac and Vrhovine in Lika-Senj county;

- Erdut, Jagodnjak and Šodolovci in Osijek-Baranja county;

- Biskupija, Civljane, Ervenik and Kistanje in Šibenik-Knin county;

- Borovo, Markušica, Negoslavci and Trpinja in Vukovar-Srijem county.

Culture

Main article: Serbian cultureProminent individuals

- see also:List of Serbs

Many famed Serbs were born on the territory of today's Croatia. These prominent individuals include: scientist Nikola Tesla who had numerous inventions, the most famous arguably being the discovery of the trophase electricity, geophysicist Milutin Milanković who confounded the Theory of Ice Age, mathematician Jovan Karamata, Austro-Hungarian General Svetozar Boroević von Bojna, Josif Runjanin (the composer of the Croatian national anthem Our Beautiful Homeland), botanist Josif Pančić and writers Dejan Medaković, whose father was an appealed member of the Croatian Parliament; Vladan Desnica, whose ancestor Ivan Desnica was from a noble family and leader of the Military Frontier; Simo Matavulj; and Sava Mrkalj, the attempted reformer of the Serbian language.

Prince Beloš of the Uroš branch of the House of Voislav, after holding numerous offices in the Hungary and Rascia, finally settled as Ban of Croatia in the 12th century.

Benedikt Kraljević was implanted by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte in 1810 as the first Episcope of the reformed Orthodox Episcopy of Dalmatia. He promoted Napoleon's reforms in the Orthodox Church in Dalmatia and worked on subjecting it to the Metropolitan of Sremski Karlovci. After his conflicts with his vikar in Boka kotorska, Gerasim Zelić, he secretly worked on Greek Catholicism as soon as the Austrian Empire acquired Dalmatia. He was forced by the people and Metropolitan Stracimirović to leave in 1823. In 1828, Josif Rajačić was elected as Episcope of Dalmatia. He fiercely resisted attempts of the Catholic Church for conversion and uniting of his subjects; his plights were continued by his successors: Živković, Mutibarić and Knežević. A certain Ivanić was Vice-ban of the Croatian Banate in 1939 - 1941.

Dr Božidar Petranović founded in Zadar in the 19th century the first Serbian literal and scientific paper in Dalmatia - the "Serbian-Dalmatian Magazine" (Srpsko-dalmatinski magazin).

Svetozar Pribićević was the main representer of the Serbs from Austro-Hungary, a politician in the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, one of the most powerful men of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and creator of the Croato-Serbian opposition with Stjepan Radić. He died as a writer in Czechoslovakia's capital, Prague in exile.

Jovo Stanisavljević Čaruga was a famous outlaw in Slavonia during the Kingdom of Yugoslavia who started his own "revolution" by stealing from the rich and giving to the poor in the likelihood of Robin Hood. Jovanka Budisavljević Broz was the wife of the leader of the World War II Yugoslav Partisans Josip Broz Tito. Jovan Rašković was the initiator of a movement for Serbian autonomy within Croatia.

Count Medo Pucić was one of the most prominent men of the 19th century Dubrovnik. Balthazzar Bogišić was the creator of the first constitution of Montenegro. Marko Car was the initiator of a movement to convert all Catholic Serbs to Orthodox Christians. Mihailo Merćep was a famous bicyclist and flight pioneer. Other famous Catholic writers were Milan Rešetar and Pero Budmani. Jovan Sundečić was also a prominent figure.

The current Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church Pavle is from Slavonia. Father of politician Nenad Čanak in Serbia is from Lika. The actor Rade Šerbedžija is from a village near Korenica.

Predrag Stojakovic is a famous basketball player. Petar Preradović was a famous Croatian writer. Milka Dudundić from Kostajnica is the wife of the Croatian President, Stjepan Mesić.

Footballer Milan Rapaić and Dado Pršo are Croats of Serb heritage.

Language

Most of the Croatian Serbs use a neo-shtokavian dialect of Serbian language with ijekavian pronunciation, while those in eastern Slavonia and Baranja mostly use ekavian pronunciation. For reference, see the following maps of dialects:

Although after dissolution of Yugoslavia respective nations started to call their language according to ethnic affiliation most Serbs in Croatia declared their language as Croatian and minor part as Serbian. Nevertheless, this shouldn't be considered a linguistic division but a personal preference.

The Serbian children receive education in standard Serbian language and the Cyrillic script in schools of eastern Slavonia, as defined by Treaty of Erdut (which re-integrated the region into Croatia in 1997/1998).

A Croatian Serb by the name of Sava Mrkalj had attempted to reform the language before Vuk Karadžić, but failed to finish his work.

Religion

Most of Serbs in Croatia are Serbian Orthodox. There is one Metropolinate divided in 4 Dioceses:

- Metropolitanate of Zagreb, Ljubljana and whole Italy, with a See in Zagreb

- Eparchy of upper Karlovac, with a See in Karlovac

- Eparchy of Dalmatia, with a See in Šibenik

- Eparchy of Osječko polje and Baranja, with a See in Dalj

- Eparchy of Slavonia, with a See in Daruvar

There are also numerous Orthodox monasteries across the country: Krka Monastery, Krupa Monastery, Dragović Monastery, Lepavina Monastery and Gomirje Monastery being one of them. Many Orthodox churches were demolished during recent war.

History

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (December 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Early Middle Ages

Toponyms and early appearances

According to Serbian linguists the first mention of Serbs is a toponym - the ancient stronghold of Srb on the river Una as early as the 9th century, citing the resemblance of the terms Serb & Srb. Croatian linguists reject this citing the noun "Srb" derived from the old Croatian verb "serbati" and denoting the spring of the river Una.

According to the Royal Frankish Annals of the Frankish historian Einhard, Prince Liudevit of Pannonia (continental Croatia) fled to the Serbs in 822, tricked the Serbian ruler by killing him and taking the power over Serbs for himself. At this time, the Serbs controlled the greater part of Dalmatia (referring to the ex Roman province).

According to one of the theories of the coming of Serbs onto the Balkan peninsula, they first came to western Dalmatia to Srb (at Una) and then Solin (near Split).

Pattern of Serb Settlement In Illyricum

According to De Administrando Imperio (chapters 32-36) from 950, written by Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos, the following lands in the south of the Roman province of Dalmatia were settled by the Serbs:

Of these areas, Pagania/Narenta bordered on a Croat area, and it was inhabited by what are described as unbaptized Serbs. The other regions did not directly border the Croat lands (although the description of the high country is unclear in the document), and were Christian.

Most of Pagania/Narenta and small southern parts of Zahumlje and Travunia and Konavli are today part of Croatia, and the rest is mostly part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Raška is located in Serbia and Duklja mostly in Montenegro.

Late Middle Ages

Most of the migrants that passed through Croatian lands were nomads. During the Tartar hordes that passed on a raiding campaign through Hungary in 1242, there is a mention of these Vlachs-Serbs as having just been settled in Cetina, Knin and Lika.

Serbian Despots have throughout the 15th century gained numerous vestiges in eastern Slavonia, where they have ruled with title Kingdom of Hungary baron because this territory is part of Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen. After the Ottoman Turks expelled the entity with the conquest of Smederevo in 1459, the Titular Serb Despots continued to maintain baron title (and territory) on Hungarian soil until 1530

There are three major Serbian Orthodox monasteries in northern Dalmatia: Krupa, started by King Stephen Uroš II Milutin in 1317. It was finished by Emperor Stephen Uroš IV Dušan in 1346; both being of the House of Nemanja. Krka was built in 1346 by the wife of ban Mladen Šubić, Jelena, sister of Stephen Dušan. Dragović was also built in the 14th century, but it was moved stone by stone during the construction of an artificial Peruča lake nearby during Communist Yugoslavia.

Early Modern Period

During the period of the Habsburg-Ottoman wars there have been constant population migrations in the territory of modern-day Croatia. Turkish invasion instigated a partial change in the ethnic aspect of Croatian lands. Large numbers of Croats abandoned their homes and moved northward seeking safety, some even going out of Croatia altogether into Austria (see Burgenland Croats). The Ottomans, on the other hand were settling, first orthodox Vlachs, and then Serbs in the area. During the following centuries, the Vlachs were assimilated by the Serbs but evidence of their existence is the 1630 document, the Statuta Wallachorum. The Habsburgs created the Military Frontier out of territory of the Croatian Crown as a defense against the Turks, and greatly expanded it further upon reconquering large territories the Ottomans conquered from Croatia. The Frontier (i.e. the "Vojna Krajina") was mostly inhabited by Serbs and Vlachs the Turks had settled there. In 1578 the area was populated largely by Orthodox Serbs. The Serbs were also fleeing to Krajina due to Ottoman persecution, and became frontiersmen for the Habsburgs in exchange for land and liberty. In addition, this was the only requirement for their permanent stay in the region. These inhabitants were required to serve a certain amount of years in the Habsburg army, after wich they would be granted land, becoming free peasants. Serbs were thus regarded as some kind of military class because of this. The tradition lasted up to the breakup of SFR Yugoslavia, where Serbs were disproportionately represented in the Croatian military and law enforcement.

The area of the Military Frontier was reunited with the Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia in the year 1881 after Bosnia and Herzegovina had been occupied by Austro-Hungary . Up to the unification with Croatia the Military Frontier Vice-Ban was always of Serb nationality. During the last two decades of the 19th century Croatian Ban (Viceroy) Khuen Hedervary (a Hungarian), relied on Serb parties in the Croatian parliament to maintain a governing majority. Because of this the Serbs came to occupy a disproportionate share of civil service posts in Croatia, causing resentment on the part of the majority Croatian population.

World War II

World War II was a dark age for Serbs in Croatia, because the Ustaše organization came to power. Ustaše had formed Independent State of Croatia and enacted racial laws aimed primarily against the Croatian Serbs. The Ustaše persecuted and killed hundreds of thousands of Orthodox Serbs and Jews . Catholic monks and other priests are alleged to have taken an active part in this struggle for the "purity" of the Croatian land. The Ustaše fascist regime set about a policy of "racial purification" against Serbs, Jews and Gypsies. It was declared that one-third of the Serbian population would be deported, one-third converted to Roman Catholicism, and one third killed. Ustaša bands actively terrorized the countryside. In addition, the Ustaše regime organized extermination camps, the most notorious one at Jasenovac where Serbs, Jews, Gypsies, and other opponents were massacred in large numbers. Between 330,000 and 500,000 of Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina were killed by the Ustasha during the entire war.

Recent history

The census of 1991 was the last one held before the war in Croatia, marked by ethnic conflict between the Orthodox Serbs and the Catholic Croats. Around 580,000 citizens declared themselves as Serbs. In the ethnic and religious makeup of population of Croatia of that time, those two sets of numbers are quoted as important:

- Croats 78.1%, Catholics 76.5%

- Serbs 12.2%, Orthodox Christians 11.1%

Two major sets of the population changed during this period - the first one during the earlier stage of the war, around 1991, and the second one during the later stage of the war, around 1995.

After the Yugoslav wars, the numbers are:

- Croats 89.6%, Catholics 87.8%

- Serbs 4.5%, Orthodox Christians 4.4%

In the earlier stages of the war, most of the Croats of eastern Slavonia, Baranja, Banija, Kordun, eastern Lika, northern Dalmatian Zagora and Konavle fled those areas as they were under Serbian military control. Most of the Serbs from Bilogora and northwestern Slavonia fled those areas as they were under Croatian military control . In later stages of the war, most of the Serbs of western Slavonia, Banija, Kordun, eastern Lika and northern Dalmatian Zagora fled those areas as they came under Croatian military control.

The population move is seen by some as a campaign of ethnic cleansing. Many incidents can be clearly explained as ethnic cleansing:

- the attacks on and the subsequent expulsion of Croatian population from the villages and towns of Škabrnja, Kijevo, Vukovar, Lovas, etc;

- and the attacks on and the subsequent expulsion of Serbian population from places such as the Medak pocket, and the events such as the Gospić massacre.

It is widely assumed to have been a war in which ethnic cleansing was generally used. But no international institution has yet established a clear pattern that would indicate that either side in the war in Croatia committed ethnic cleansing on the scale of the whole country, including the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia at The Hague. The leader of the rebel Serbs Milan Babić was indicted, plead guilty and was convicted for persecutions on political, racial and religious grounds, a crime against humanity, which combined with the content of his indictment implies that there was ethnic cleansing on the whole area of Krajina.

The war ended with military victories of the Croatian government in 1995 and subsequent peaceful reintegration of the remaining renegade territory in eastern Slavonia in 1998. The exodus of the Krajina Serbs in 1995 was prompted by the advance of the Croatian troops, but was mostly self-organized rather than forced. All of them were officially called upon to stay shortly before the operation, and called to return after the end of the hostilities, with varying but increasing degrees of guarantees from the Croatian government. Everyone that participated in the rebellion but committed no crimes were pardoned by the government in 1997.

Two thirds of the Serbs remain in exile. The other third either returned or had remained in Zagreb and other parts of Croatia not directly hit by war. But most other Croat refugees returned to their homes.

The current reasons why many Serb refugees still have not returned vary:

- Integration at the current place of displacement.

- Appalling economic conditions in areas they fled from, by and large rural ones.

- Fear of prosecution for war crimes. The Croatian legal system, like the ICTY, has secret lists of war crimes suspects, and many returnees were caught by surprise when the authorities arrested them upon re-entering the country.

- Fear of retribution.

- Ethnic discrimination.

- Unfavorable property laws.

In 2004/2005, the government of Serbia had about 140,000 refugees of unsolved status from Croatia registered on its territory. About 13,000 house repair demands were pending with the Croatian authorities.

The property laws allegedly favor Croats who immigrated into the previously Serb-dominant areas after having been forced out of Bosnia and Herzegovina by the Serbs. Under the current law, a person who occupies someone else's previously vacated house and does not have alternative accommodation (such as their own home or a place in a refugee camp), is allowed to stay in someone else's private property as a refugee, without being charged for squatting. The number of such individuals and families has dropped significantly in the 2000s, and a certain amount of property was returned to its previous owners. However, at the same time not all of the former refugees actually left the same houses, and instead remained in the occupied houses illegally. In 2004, the authorities noted around 1,400 houses still occupied by former refugees, and in 2005, this number was reduced to 385 housing units.

With regard to reparation of war damages, the plight of the Serbs is similar to the plight of the Croats - the money and/or resources offered by the government often amount to only a small fraction of the value of the people's properties prior to the war. There are fewer options to reinstate people's livelihood - it's not really likely to get back one's livestock, or a job in a destroyed factory. In a recent public protest, a group of Serbs from Vukovar who had worked in the Borovo shoe factory demanded that their pre-war employment was honoured as it was for the Croatian employees which has stayed loyal to Croatia during war. Because during Krajina period Serb workers has made payment outside Croatia pension funds (in Krajina pension funds) state position is that they have lost this and many others workers rights .

This has created the situation where many if not most Serbs from the former RSK areas only come to get some reparation and do not continue to actually live in Croatia.

The successive post-war Governments have consistently worked with the local Serb representatives to rectify the war-related problems, with the support of the international community and under the watch of the independent media, but at the same time, cooperation on the lower levels has been lacking. The participation of the largest Serbian party SDSS in the Croatian Government of Ivo Sanader has eased tensions to an extent, but the refugee situation is still politically sensitive. In 2005 and 2006, the presidents Mesić of Croatia and Tadić of Serbia exchanged official visits and both met with the respective national minorities in each country, hoping to improve relations.

On the 2007 elections for local National Councils, there were 274,968 eligible Croatian voters of Serb ethnicity for the County national councils. Only 23,325 voted or 8.48%. For the Civic National Councils there were 131,717 registered Serb voters, 8,413 or 6.39% voted. And for the municipal Serb national councils with 76,697 eligible voters, 11,161 or 14.55% voted.

- An old man of presumably Serb nationality. Unlike the beards that Chetniks wear, the beard seen in the picture is not related to the symbolic struggle against the occupation. An old man of presumably Serb nationality. Unlike the beards that Chetniks wear, the beard seen in the picture is not related to the symbolic struggle against the occupation.

- An replica of an outfit that a typical soldier from Krajina might wear. An replica of an outfit that a typical soldier from Krajina might wear.

See also

External links

- The Serbs in the Former SR of Croatia

- Prosvjeta - Serb Cultural Society

- Reference to etymology of the name Srb

- Reference to Istarski Razvod - related to etymology of Srb

References

- The New Encyclopedia Britannica, Edition 1986 Reference: EB, Edition 1986, Macropedia, Vol 29, page 1061 Entry: Yugoslavia, Croatia, History

- The New Encyclopedia Britannica, Edition 1986 Reference: EB, Edition 1986, Macropedia, Vol 29, page 1061 Entry: Yugoslavia, Croatia, History

- Croatian census 2001 - see under "Crostat Databases"->"Censuses"

- Development of Astronomy among Serbs II, Publications of the Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade, , Belgrade: M. S. Dimitrijević, 2002.

- Vladimir Ćorović. Illustrated History of Serbs, Books 1 - 6. Belgrade: Politika and Narodna Knjiga, 2005

- Nicholas J. Miller. Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia before the First World War, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997.

- In an interview on Fokus (30 September 2005), Croat academic Petar Simunovic explained that the name of Srb originates from an old Croatian verb serbati, srebati meaning "to sip", from which the noun "srb" has been derived. Thus "srb" denotes the spring of river Una, where the village lies. Compare this with the villages of Srbani (near Pula), and Srbinjak, both in Istria, which clearly have nothing to do with the Serbian name. The Istarski razvod from 13th century mentions the name of srbar, meaning a water spring.