This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 2over0 (talk | contribs) at 05:47, 14 June 2008 (Undid revision 219144795 by 140.211.82.4 (talk) restore useful link). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:47, 14 June 2008 by 2over0 (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 219144795 by 140.211.82.4 (talk) restore useful link)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Chelation therapy is the administration of chelating agents to remove heavy metals from the body. For the most common forms of heavy metal intoxication—those involving lead, arsenic or mercury—the standard of care in the USA dictates the use of dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) or Dimercaprol. Other chelating agents, such as 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid (DMPS) and alpha lipoic acid (ALA), are used in conventional and alternative medicine.

Discovery and history in medicine

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Chelating agents were introduced into medicine as a result of the use of poison gas in World War I. The first widely used chelating agent—the organic dithiol compound dimercaprol, also named British Anti-Lewisite or BAL—was used as an antidote to the arsenic-based poison gas, Lewisite. The sulphur atoms in BAL's mercaptan groups strongly bond to the arsenic in Lewisite, forming a water-soluble compound that entered the bloodstream, allowing it to be removed from the body by the kidneys and liver. BAL had severe side-effects.

After World War II, a large number of navy personnel suffered from lead poisoning as a result of their jobs repainting the hulls of ships. The medical use of EDTA as a lead chelating agent was introduced. Unlike BAL, it is a synthetic amino acid and contains no mercaptans. While EDTA had some uncomfortable side effects, they were not as severe as BAL.

In the 1960s, BAL was modified into DMSA, a related dithiol with far fewer side effects. DMSA quickly replaced both BAL and EDTA, becoming the US standard of care for the treatment of lead, arsenic, and mercury poisoning, which it remains today.

Research in the former Soviet Union led to the introduction of DMPS, another dithiol, as a mercury-chelating agent. The Soviets also introduced ALA, which is transformed by the body into the dithiol dihydrolipoic acid, a mercury- and arsenic-chelating agent. DMPS has experimental status in the US FDA, while ALA is a common nutritional supplement.

Since the 1970s, iron chelation therapy has been used as an alternative to regular phlebotomy to treat excess iron stores in people with haemochromatosis.

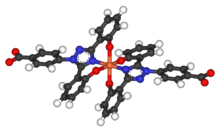

Other chelating agents have been discovered. They all function by making several chemical bonds with metal ions, thus rendering them much less chemically reactive. The resulting complex is water-soluble, allowing it to enter the bloodstream and be excreted harmlessly.

EDTA chelation is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating lead poisoning and heavy metal toxicity.

Medical use

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Chelation therapy is used as a treatment for acute mercury, iron (including in cases of thalassemia), arsenic, lead, uranium, plutonium and other forms of toxic metal poisoning. The chelating agent may be administered intravenously, intramuscularly, or orally, depending on the agent and the type of poisoning.

One example of successful chelation therapy is the case of Harold McCluskey, a nuclear worker who became badly contaminated with americium in 1976. He was treated with diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) over many years, removing 41 MBq (1.1 mCi) of americium from his body. His death, 11 years later, was from unrelated causes.

Several chelating agents are available, having different affinities for different metals. Common chelating agents include:

- Alpha lipoic acid (ALA)

- Aminophenoxyethane-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA)

- Defarasirox

- Deferiprone

- Deferoxamine

- Diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA)

- Dimercaprol (BAL)

- Dimercapto-propane sulfonate (DMPS)

- Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA)

- Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (calcium disodium versante) (CaNa2-EDTA)

- Ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA)

- D-penicillamine

Use in alternative medicine

Alternative medicine uses chelation therapy in the treatment of heart disease. Currently there is a US National Insitutes of Health trial (TACT) being conducted on the chelation therapy's efficacy in treating heart disease. The proposed study has been criticized as unnecessary and possibly dangerous.

Cilantro

Cilantro (coriander) has been tested in mice, and is present in numerous alternative medications. Although cilantro was widely described as a chelator of lead, mercury, or other heavy metals in internet literature, and is often used as such, there is little research about such claims.

Heart disease

Some alternative practitioners use chelation to treat hardening of the arteries. The use of EDTA chelation therapy as a treatment for coronary artery disease is currently being studied by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, but no claims or findings are expected before 2009. Chelation therapy is not approved by the FDA to treat coronary artery disease.

The American Heart Association contends that there is currently "no scientific evidence to demonstrate any benefit from this form of therapy" and that the "United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the American College of Cardiology all agree with the American Heart Association" that "there have been no adequate, controlled, published scientific studies using currently approved scientific methodology to support this therapy for cardiovascular disease."

Autism

Based on the speculation that heavy metal poisoning may trigger the symptoms of autism, some parents have turned to alternative medicine practitioners who provide chelation therapy. However, the only evidence to support this belief is anecdotal. There is strong epidemiological evidence that refutes links between environmental triggers, in particular thimerosal-containing vaccines and the onset of autistic symptoms. No scientific data supports the claim that the mercury in the vaccine preservative thiomersal causes autism or its symptoms, and there is no scientific support for chelation therapy as a treatment for autism.

The hypothesis of mercury poisoning as a cause for autism was proposed by Bernard, Enayati, Roger, Binstock, and Redwood in 2002. These authors stated that symptoms of autism arise from exposure to mercury. They further state that symptoms of autism tend to emerge when children are administered vaccines, the rise in children with autism in the 1990’s coincided with the introduction of two mercury-containing immunizations, and finally, patients with autism have been found to have levels of mercury in their systems. An important problem with this theory is the fact that the symptoms of autism do not perfectly resemble symptoms of mercury poisoning. Though mercury poisoning can cause impaired social interactions, communication problems, and stereotypic behaviors, as seen in autism, it also causes “ataxia, constricted visual fields, peripheral neuropathy, hypertension, skin eruption, and thrombocytopenia” - symptoms not seen in children with autism. Thimerosal, the mercury-containing preservative found in vaccines, has been removed from nearly all childhood immunizations. In one state study, however, the Caifornia Department of Developmental Services found that the prevalence of autism increased from January 1995 to March 2007, concluding that exposure to thimerosal does not lead to autism. Nevertheless, caregivers of children with autism have sought out treatment to rid mercury and other heavy metals from the body, in a process known as chelation.

Chelation therapy was used by the British after World War II to remove arsenic, lead, and other metals created by the during the war due to lack of materials. Patients’ conditions improved as these metals were removed from their bodies. Today, chelation therapy is used to rid the body of toxic metals such as lead and mercury. Doctors should take a blood test to assess current kidney and liver function, nutrient status, and blood-lipid levels before chelation therapy begins. A gluten-free, casein-free (GFCF) diet and supplemental changes, including shots of vitamin B12, may be used. Treatment may be applied to the skin via a transdermal patch. Another treatment is administered intravenously, a process that takes 2-3 hours, costs about $100 per treatment, and 20-30 treatments are often required.

Some common chelating agents are EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), DMSA (sodium 2,3 dimercaptopropane-1 sulfate), TTFD (thiamine tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide), and DMPS (2,3 dimercaptosuccinic acid). EDTA and DMSA are only approved for the removal of lead by the Food and Drug Administration while DMPS and TTFD are not approved by the FDA. These drugs bind to heavy metals in the body and prevent them from binding to other agents. They are then excreted from the body. The chelating process also removes vital nutrients such as vitamins C and E, therefore these must be supplemented.

Some parents of children with autism have reported significant gains in their children’s symptoms following chelation therapy. They contend that within weeks of the initial treatment, their children have made drastic improvements in behavior and social engagement. Younger children have reportedly made faster and more significant results. However, other parents have stated that chelation therapies made no difference in their children’s developmental outcomes.

There are significant risks associated with the use of chelation for the treatments of autism. The deaths of two children were reported due to hypocalemia and cardiac arrest after receiving chelation therapy. Long-term use of the chelating agent SMSA can cause liver damage, zinc deficiency, and bone marrow suppression. Mineral deficiencies, cardiovascular effects (blood pressure drop), kidney problems, and the possibility of distributing mercury throughout the body may also occur. However, using a combination of chelators, supplements, diet changes, and regular lab tests can reportedly reduce the risk of side effects.

Because of the lack of empirical support in controlled studies and the possibility of dangerous side effects, chelation therapy for the treatment of autism is not recommended. The most effective known interventions for children with autism are educational and behavioral therapies.

Controversy

The efficacy, safety, and much of the theory behind these alternative practices are disputed by the medical community. In 2001, researchers at the University of Calgary reported that cardiac patients receiving chelation therapy fared no better than those who received placebo treatment.

In 2003, the Supreme Court of Missouri, in State Board of Registration for the Healing Arts v. McDonagh, 123 S.W.3d 146, overturned a decision of the State Board of Registration sanctioning a doctor who used chelation therapy for the treatment of heart disease. The Court held that the therapy was not harming patients, and the standard for determining repeated negligence in using an alternative therapy such as chelation is not whether it is popular or commonly accepted by the medical community, but rather whether heart specialists would consider its use to be reasonable.

In 1998, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) charged that the web site of the American College for Advancement in Medicine (ACAM) and a brochure they published had made false or unsubstantiated claims. In December 1998, the FTC announced that it had secured a consent agreement barring ACAM from making unsubstantiated advertising claims that chelation therapy is effective against atherosclerosis or any other disease of the circulatory system.

Prevalence

The American College for Advancement in Medicine (ACAM), a not-for-profit 501(c)(6) organization which promotes chelation therapy, claims that 800,000 patient visits for chelation therapy, with an average of 40 visits per patient, were made in the United States in 1997.

Side effects and safety concerns

There is a low occurrence of side effects when chelation is used at the dose and infusion rates approved by the U.S. FDA. A burning sensation at the site of delivery into the vein is common. Rarer side effects include fever, headache, nausea, stomach upset, vomiting, a drop in blood pressure, and hypocalcemia. Kidney toxicity is a safety concern, but a rare occurrence. When EDTA is not administered correctly, more serious side effects can occur.

Chelation therapy can be hazardous. In August 2005, botched chelation therapy killed a 5-year-old autistic boy, a nonautistic child died in February 2005, and a nonautistic adult died in August 2003. These deaths were due to cardiac arrest caused by hypocalcemia during chelation therapy.

References

- "Hemochromatosis: Monitoring and Treatment". National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD). 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- ^ "Questions and Answers: The NIH Trial of EDTA Chelation Therapy for Coronary Artery Disease". National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- Ernst E (2000). "Chelation therapy for coronary heart disease: An overview of all clinical investigations". Am. Heart J. 140 (1): 139–41. doi:10.1067/mhj.2000.107548. PMID 10874275.

- NCCAMN.Trial to assess chelation therapy

- Why the NIH Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT) Should Be Abandoned

- Aga M, Iwaki K, Ueda Y; et al. (2001). "Preventive effect of Coriandrum sativum (Chinese parsley) on localized lead deposition in ICR mice". Journal of ethnopharmacology. 77 (2–3): 203–8. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00299-9. PMID 11535365.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Omura Y, Beckman SL (1995). "Role of mercury (Hg) in resistant infections & effective treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis and Herpes family viral infections (and potential treatment for cancer) by removing localized Hg deposits with Chinese parsley and delivering effective antibiotics using various drug uptake enhancement methods". Acupuncture & electro-therapeutics research. 20 (3–4): 195–229. PMID 8686573.

- Omura Y, Shimotsuura Y, Fukuoka A, Fukuoka H, Nomoto T (1996). "Significant mercury deposits in internal organs following the removal of dental amalgam, & development of pre-cancer on the gingiva and the sides of the tongue and their represented organs as a result of inadvertent exposure to strong curing light (used to solidify synthetic dental filling material) & effective treatment: a clinical case report, along with organ representation areas for each tooth". Acupuncture & electro-therapeutics research. 21 (2): 133–60. PMID 8914687.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Millet, John. "Cilantro, Chlorella and Heavy Metals" (PDF). Medical Herbalism. 14 (4). Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- "Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT)". U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "American Heart Association: Chelation Therapy". Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- Doja A, Roberts W (2006). "Immunizations and autism: a review of the literature". Can J Neurol Sci. 33 (4): 341–6. PMID 17168158.

- Thompson WW, Price C, Goodson B; et al. (2007). "Early thimerosal exposure and neuropsychological outcomes at 7 to 10 years". N Engl J Med. 357 (13): 1281–92. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa071434. PMID 17898097.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weber W, Newmark S (2007). "Complementary and alternative medical therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism". Pediatr Clin North Am. 54 (6): 983–1006. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2007.09.006. PMID 18061787.

- Blakeslee, Sandra (2004-05-19). "Panel Finds No Evidence To Tie Autism To Vaccines". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-01. "An examination of scientific studies worldwide has found no convincing evidence that vaccines cause autism, according to a committee of experts appointed by the Institute of Medicine."

- Bernard, S., Enayati, A., Roger, T., Binstock, T., & Redwood, L. (2002). The role of mercury in the pathogenesis of autism. Molecular Psychiatry, 7, S42-S43.

- Bernard, S., Enayati, A., Roger, T., Binstock, T., & Redwood, L. (2002). The role of mercury in the pathogenesis of autism. Molecular Psychiatry , 7, S42-S43.

- Bernard, S., Enayati, A., Roger, T., Binstock, T., & Redwood, L. (2002). The role of mercury in the pathogenesis of autism. Molecular Psychiatry , 7, S42-S43.

- Ng, D. K.-K., Chan, C.-H., Soo, M.-T., & Lee, R. S.-Y. (2007). Low-level chronic mercury exposure in children and adolescents: meta-analysis. Pediatrics International , 49, 80-87.

- Schechter, R., & Grether, J. K. (2008). Continuing increases in autism reported to California's developmental services system. Archives of General Psychiatry , 65 (1), 19-24.

- Nash, R. A. (2005). Metals in medicine. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine , 11 (4), 18-25.

- Klotter, J. (2006). Chelation for autism. Townsend Letter: The Examiner of Alternative Medicine , 30, p. 273.

- Bridges, S. (2006). The promise of chelation. Mothering , 54-61.

- Klotter, J. (2006). Chelation for autism. Townsend Letter: The Examiner of Alternative Medicine , 30, p. 273.

- Bridges, S. (2006). The promise of chelation. Mothering , 54-61.

- Bridges, S. (2006). The promise of chelation. Mothering , 54-61.

- Laidler, J. R. (n.d.). Through the looking glass: my involvment with autism quackery. Retrieved May 26, 2008, from Autism Watch: http://www.autism-watch.org/about/bio2.shtml

- Schechtman, M. A. (2007). Scientifically unsupported therapies in the treatment of young children with autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Annals , 37 (9), 639-645.

- Klotter, J. (2006). Chelation for autism. Townsend Letter: The Examiner of Alternative Medicine , 30, p. 273.

- Bridges, S. (2006). The promise of chelation. Mothering , 54-61.

- Knudtson ML, Wyse DG, Galbraith PD; et al. (2002). "Chelation therapy for ischemic heart disease: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 287 (4): 481–6. doi:10.1001/jama.287.4.481. PMID 11798370.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "American College for Advancement in Medicine, File No. 962 3147, Docket No. C-3882". Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- "Medical Association Settles False Advertising Charges Over Promotion of 'Chelation Therapy'". Quackwatch. December 8, 1998. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - "Physician Group Backs New NIH Chelation Therapy Study For Heart Disease" (Press release). American College for Advancement in Medicine. August 14, 2002. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Brown MJ, Willis T, Omalu B, Leiker R (2006). "Deaths resulting from hypocalcemia after administration of edetate disodium: 2003–2005". Pediatrics. 118 (2): e534-6. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0858. PMID 16882789.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Quackwatch "Chelation Therapy: Unproven Claims and Unsound Theories" by Sam Green

- JAMA and Archives Journals (2008, January 8). Autism: Removing Thimerosal From Vaccines Did Not Reduce Autism Cases In California, Report Finds. ScienceDaily. Retrieved January 9, 2008, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2008/01/080107181551.htm

| Chelating agents / chelation therapy (V03AC, others) | |

|---|---|

| Copper | |

| Iron | |

| Lead | |

| Thallium | |

| Other | |

| |