This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Caspian blue (talk | contribs) at 16:44, 1 August 2008 (rvv by 203.165.124.61 blanking of cited info/ academic reliable sources, use talk page first). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:44, 1 August 2008 by Caspian blue (talk | contribs) (rvv by 203.165.124.61 blanking of cited info/ academic reliable sources, use talk page first)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Rape of Nanking" redirects here. For Iris Chang's book, see The Rape of Nanking (book).| The Nanking Massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

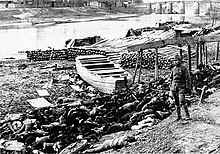

Massacre victims on the shore of Yangtze River with a Japanese soldier standing nearby Massacre victims on the shore of Yangtze River with a Japanese soldier standing nearby | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 南京大屠殺 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 南京大屠杀 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 南京事件 南京大虐殺 | ||||||

| |||||||

The Nanking Massacre, commonly known as the Rape of Nanking, was an infamous war crime committed by the Japanese military in Nanjing (Nanking), then the capital of the Republic of China, after it fell to the Imperial Japanese Army on December 13, 1937. The duration of the massacre is not clearly defined, although the violence lasted well into the next six weeks, until early February 1938.

During the occupation of Nanking, the Japanese army committed numerous atrocities, such as rape, looting, arson and the execution of prisoners of war and civilians. Although the executions began under the pretext of eliminating Chinese soldiers disguised as civilians, it is claimed that a large number of innocent men were intentionally misidentified as enemy combatants and executed as the massacre gathered momentum. A large number of women and children were also killed, as rape and murder became more widespread.

According to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, estimates made at a later date indicate that the total number of civilians and prisoners of war murdered in Nanking and its vicinity during the first six weeks of the Japanese occupation was over 200,000. That these estimates are not exaggerated is borne out by the fact that burial societies and other organizations counted more than 155,000 buried bodies. Most were bound with their hands tied behind their backs. These figures do not take into account those persons whose bodies were destroyed by burning, by throwing them into the Yangtze River, or otherwise disposed of by the Japanese. The extent of the atrocities is debated between China and Japan, with numbers ranging from some Japanese claims of several hundred, to the Chinese claim of a non-combatant death toll of 300,000. A number of Japanese researchers consider 100,000 – 200,000 to be an approximate value. Other nations usually believe the death toll to be between 150,000–300,000. The casualty count of 300,000 was first promulgated in January of 1938 by Harold Timperley, a journalist in China during the Japanese invasion, based on reports from contemporary eyewitnesses. Other sources, including Iris Chang's The Rape of Nanking, also conclude that the death toll reached 300,000. In December 2007, newly declassified U.S. government documents revealed an additional toll of around 500,000 in the area surrounding Nanking before it was occupied.

In addition to the number of victims, some Japanese nationalists have even disputed whether the atrocity ever happened. While the Japanese government has acknowledged the incident did occur, some Japanese nationalists have argued, partly using the Imperial Japanese Army's claims at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, that the death toll was military in nature and that no such civilian atrocities ever occurred. This claim has been criticised by various figures, citing statements of non-Chinese at the Tribunal, other eyewitnesses and by photographic and archaeological evidence that civilian deaths did occur.

Condemnation of the massacre is a major focal point of Chinese nationalism. In Japan, however, public opinion over the severity of the massacre remains widely divided — this is evidenced by the fact that whereas some Japanese commentators refer to it as the 'Nanking massacre' (南京大虐殺, Nankin daigyakusatsu), others use the more ambivalent term 'Nanking Incident' (南京事件, Nankin jiken). However, this term can also refer to a separate Nanjing Incident that occurred during the 1927 Nationalist seizure of the city as a part of the Northern Expedition, in which foreigners in the city were attacked. The 1937 massacre and the extent of its coverage in school textbooks continues to be a point of contention and controversy in Sino-Japanese relations.

Historical background

Invasion of China

By August of 1937, in the midst of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Imperial Japanese Army encountered strong resistance from the Kuomintang (KMT, Chinese Nationalist Party) army in the Battle of Shanghai. The battle caused high casualties on both sides as they were worn down by attrition in hand-to-hand combat. On August 6 1937, Hirohito personally ratified his army's proposition to remove the constraints of international law on the treatment of Chinese prisoners. This directive also advised staff officers to stop using the term "prisoner of war".

On the way from Shanghai to Nanjing, Japanese soldiers committed numerous atrocities, showing that the Nanking Massacre was not an isolated incident. The most infamous event was the "contest to kill 100 people using a sword" . By mid-November, the Japanese had captured Shanghai with the help of naval and aerial bombardment. The General Staff Headquarters in Tokyo decided not to expand the war, due to the high casualties incurred and the low morale of the troops.

Approach towards Nanking

As the Japanese army drew closer to Nanking, Chinese civilians fled the city in droves, and the Chinese military put into effect a scorched earth campaign, aimed at destroying anything that might be of value to the invading Japanese army. Targets within and outside of the city walls—such as military barracks, private homes, the Chinese Ministry of Communication, forests and even entire villages—were burnt to cinders, at an estimated value of 20 to 30 million (1937) US dollars.

On December 2, Emperor Showa nominated one of his uncles, Prince Asaka, as commander of the invasion. It is difficult to establish if, as a member of the imperial family, Asaka had a superior status to general Iwane Matsui, who was officially the commander in chief, but it is clear that, as the top ranking officer, he had authority over division commanders, lieutenant-generals Kesago Nakajima and Heisuke Yanagawa.

Nanking Safety Zone

Main article: Nanking Safety ZoneMany westerners were living in the city at that time, conducting trade or on missionary trips. As the Japanese army began to launch bombing raids over Nanjing, all of them except 22 people fled to their respective countries. Siemens businessman John Rabe stayed behind and formed a committee, called the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone. Rabe was elected as its leader, in part because of his status as a Nazi and the existence of the German-Japanese bilateral Anti-Comintern Pact. This committee established the Nanking Safety Zone in the western quarter of the city. The Japanese government had agreed not to attack parts of the city that did not contain Chinese military, and the members of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone managed to persuade the Chinese government to move all their troops out of the area. It is said Rabe rescued 200,000 - 250,000 Chinese people.

The Japanese did respect the Zone to an extent; no shells entered that part of the city leading up to the Japanese occupation except a few stray shots. During the chaos following the attack of the city, some were killed in the Safety Zone, but the atrocities in the rest of the city were far greater by all accounts.

Siege of the city

On December 7, the Japanese army issued a command to all troops, advising that because occupying a foreign capital was an unprecedented event for the Japanese military, those soldiers who " any illegal acts", "dishonor the Japanese Army", "loot", or "cause a fire to break out, even because of their carelessness" would be severely punished. The Japanese military continued to march forward, breaching the last lines of Chinese resistance, and arriving outside the walled city of Nanjing on December 9. At noon, the military dropped leaflets into the city, urging the surrender of Nanjing within 24 hours:

"The Japanese Army, one million strong, has already conquered Changshu. We have surrounded the city of Nanking… The Japanese Army shall show no mercy toward those who offer resistance, treating them with extreme severity, but shall harm neither innocent civilians nor Chinese military who manifest no hostility. It is our earnest desire to preserve the East Asian culture. If your troops continue to fight, war in Nanking is inevitable. The culture that has endured for a millennium will be reduced to ashes, and the government that has lasted for a decade will vanish into thin air. This commander-in-chief issues ills to your troops on behalf of the Japanese Army. Open the gates to Nanking in a peaceful manner, and obey the ollowing instructions."

The Japanese awaited an answer. When no Chinese envoy had arrived by 1:00 p.m. the following day, General Matsui Iwane issued the command to take Nanjing by force. On December 12, after two days of Japanese attack, under heavy artillery fire and aerial bombardment, General Tang Sheng-chi ordered his men to retreat. What followed was nothing short of chaos. Some Chinese soldiers stripped civilians of their clothing in a desperate attempt to blend in, and many others were shot in the back by their own comrades as they tried to flee. Those who actually made it outside the city walls fled north to the Yangtze, only to find that there were no vessels remaining to take them. Some then jumped into the wintry waters and drowned.

The Japanese entered the walled city of Nanjing on December 13 and faced little military resistance.

Atrocities begin

Eyewitness accounts from the period state that over the course of six weeks following the fall of Nanjing, Japanese troops engaged in rape, murder, theft, and arson. The most reliable accounts came from foreigners who opted to stay behind in order to protect Chinese civilians from certain harm, including the diaries of John Rabe and Minnie Vautrin. Others include first-person testimonies of the Nanjing Massacre survivors. Still more were gathered from eyewitness reports of journalists, both Western and Japanese, as well as the field diaries of certain military personnel. An American missionary, John Magee, stayed behind to provide a 16mm film documentary and first-hand photographs of the Nanjing Massacre. This film is called the Magee Film. It is often quoted as an important evidence of the Nanjing Massacre. In addition, although few Japanese veterans have admitted to having participated in atrocities in Nanjing, some—most notably Shiro Azuma—have admitted to criminal behavior.

Immediately after the city's fall, a group of foreign expatriates headed by John Rabe formed the 15-man International Committee on November 22 and drew up the Nanking Safety Zone in order to safeguard the lives of civilians in the city, where the population ran from 200,000 to 250,000. It is likely that the civilian death toll would have been higher had this safe haven not been created. Rabe and American missionary Lewis S. C. Smythe, the secretary of the International Committee, who was also a professor of sociology at the University of Nanking, recorded atrocities of the Japanese troops and filed reports of complaints to the Japanese embassy.

Rape

It is a horrible story to relate; I know not where to begin nor to end. Never have I heard or read of such brutality. Rape: We estimate at least 1,000 cases a night and many by day. In case of resistance or anything that seems like disapproval there is a bayonet stab or a bullet.

— James McCallum, letter to his family, 19 December 1937

There probably is no crime that has not been committed in this city today. Thirty girls were taken from the language school last night, and today I have heard scores of heartbreaking stories of girls who were taken from their homes last night—one of the girls was but 12 years old… Tonight a truck passed in which there were eight or ten girls, and as it passed they called out "Jiu ming! Jiu ming!"—save our lives.

— Minnie Vautrin's diary, 16 December 1937

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East stated that 20,000 women were raped, including infants and the elderly. Rapes were often performed in public during the day, sometimes in front of spouses or family members that were tied up and forced to watch. A large number of them were systematized in a process where soldiers would search door-to-door for young girls, with many women taken captive and gang raped. The women were often then killed immediately after the rape, often through mutilation, including breasts being cut off; or stabbing by bamboo (usually very long sticks), bayonet, butcher's knife and other objects into the vagina. According to some testimonies, other women were forced into military prostitution as comfort women. There are even stories of Japanese troops forcing families to commit acts of incest. Sons were forced to rape their mothers, fathers were forced to rape daughters. One pregnant woman who was gang-raped by Japanese soldiers gave birth only a few hours later; the baby was perfectly healthy (Robert B. Edgerton, Warriors of the Rising Sun). Monks who had declared a life of celibacy were forced to rape women for the amusement of the Japanese. Chinese men were forced into intercourse with corpses and infants; some were forced to have their penises cut off by bayonets for "humorous" reasons as detailed by some Japanese soldiers.} Testicles were also cut off - with some men being forced to eat them. Farmers were forced to commit zoophiliac acts with their livestock. Men were tied up by Japanese soldiers and hit in the crotch area with bamboo sticks. Any resistance would be met with summary executions. While the rape peaked immediately following the fall of the city, it continued for the duration of the Japanese occupation.

Murder

Various foreign residents in Nanking at the time recorded their experiences with what was going on in the city:

Robert Wilson in his letter to his family: The slaughter of civilians is appalling. I could go on for pages telling of cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief. Two bayoneted corpses are the only survivors of seven street cleaners who were sitting in their headquarters when Japanese soldiers came in without warning or reason and killed five of their number and wounded the two that found their way to the hospital.

- John Magee in his letter to his wife: They not only killed every prisoner they could find but also a vast number of ordinary citizens of all ages.... Just the day before yesterday we saw a poor wretch killed very near the house where we are living.

- Robert Wilson in another letter to his family: They bayoneted one little boy, killing him, and I spent an hour and a half this morning patching up another little boy of eight who had five bayonet wounds including one that penetrated his stomach, a portion of omentum was outside the abdomen.

Immediately after the fall of the city, Japanese troops embarked on a determined search for former soldiers, in which thousands of young men were captured. Many were taken to the Yangtze River, where they were machine-gunned so their bodies would be carried down to Shanghai. The Japanese troops gathered 1,300 Chinese soldiers and civilians at Taiping Gate and killed them. The victims were blown up with landmines, then doused with petrol before being set on fire. Those that were left alive afterwards were killed with bayonets. Some people were beaten to death. The Japanese also summarily executed many pedestrians on the streets, usually under the pretext that they might be soldiers disguised in civilian clothing.

Thousands were led away and mass-executed in an excavation known as the "Ten-Thousand-Corpse Ditch", a trench measuring about 300m long and 5m wide. Since records were not kept, estimates regarding the number of victims buried in the ditch range from 4,000 to 20,000. However, most scholars and historians consider the number to be more than 12,000 victims.

Women and children were not spared from the horrors of the massacres. Often, Japanese soldiers cut off the breasts, impaled them with bayonets until the blade protruded out of the back, disemboweled them, or in the case of pregnant women, cut open the uterus, removed the fetus. Witnesses recall Japanese soldiers throwing babies into the air and catching them with their bayonets. Pregnant women were often the target of murder, as they would often be bayoneted in the belly, sometimes after rape. Many women were first brutally raped then killed. The actual scene of this massacre is introduced in detail in the documentary film of the movie "The Battle of China".

The Konoe government was well aware of the atrocities. On 17 January, Foreign minister Koki Hirota received a telegram written by Manchester Guardian correspondent H.J. Timperley intercepted by the occupation government in Shanghai. In this telegram, Timperley wrote:

Since return Shanghai few days ago I investigated reported atrocities committed by Japanese Army in Nanking and elsewhere. Verbal accounts reliable eye-witnesses and letters from individuals whose credibility beyond question afford convincing proof Japanese Army behaved and continuing behave in fashion reminiscent Attila his Huns. less than three hundred thousand Chinese civilians slaughtered, many cases cold blood.

Theft and arson

One-third of the city was destroyed as a result of arson. According to reports, Japanese troops torched newly-built government buildings as well as the homes of many civilians. There was considerable destruction to areas outside the city walls. Soldiers pillaged from the poor and the wealthy alike. The lack of resistance from Chinese troops and civilians in Nanjing meant that the Japanese soldiers were free to divide up the city's valuables as they saw fit. This resulted in the widespread looting and burglary.

Death toll estimates

There is great debate as to the extent of the war atrocities in Nanking, especially regarding estimates of the death toll. The issues involved in calculating the number of victims are largely based on the debatees' definitions of the geographical range and the duration of the event, as well as their definition of the victims.

Range and duration

The most conservative viewpoint is that the geographical area of the incident should be limited to the few km of the city known as the Safety Zone, where the civilians gathered after the invasion. Many Japanese historians seized upon the fact that during the Japanese invasion there were only 200,000–250,000 citizens in Nanking as reported by John Rabe, to argue that the PRC's estimate of 300,000 deaths is a vast exaggeration.

However, many historians include a much larger area around the city. Including the Xiaguan district (the suburbs north of Nanjing city, about 31 km in size) and other areas on the outskirts of the city, the population of greater Nanjing was running between 535,000 and 635,000 civilians and soldiers just prior to the Japanese occupation. Some historians also include six counties around Nanjing, known as the Nanjing Special Municipality.

The duration of the incident is naturally defined by its geography: the earlier the Japanese entered the area, the longer the duration. The Battle of Nanking ended on December 13, when the divisions of the Japanese Army entered the walled city of Nanking. The Tokyo War Crime Tribunal defined the period of the massacre to the ensuing six weeks. More conservative estimates say the massacre started on December 14, when the troops entered the Safety Zone, and that it lasted for 6 weeks. Historians who define the Nanking Massacre as having started from the time the Japanese Army entered Jiangsu province push the beginning of the massacre to around mid-November to early December (Suzhou fell on November 19), and stretch the end of the massacre to late March 1938. Naturally, the number of victims proposed by these historians is much greater than more conservative estimates.

Various estimates

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East estimated in two (seemingly conflicting) reports that "over 200,000" civilians and prisoners of war were murdered during the first six weeks of the occupation. That number was based on burial records submitted by charitable organizations—including the Red Swastika Society and the Chung Shan Tang (Tsung Shan Tong)—the research done by Smythe, and some estimates given by survivors.

In 1947, at the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal, the verdict for Lieutenant General Hisao Tani—the commander of the 6th Division—quoted a figure of more than 300,000 dead. This estimate was made from burial records and eyewitness accounts. It concluded that some 190,000 were illegally executed at various execution sites and 150,000 were killed one-by-one. The death toll of 300,000 is the official estimate engraved on the stone wall at the entrance of the "Memorial Hall for Compatriot Victims of the Japanese Military's Nanking Massacre" in Nanjing.

Japanese historians, depending on their definition of the geographical and time duration of the killings, give wide-ranging estimates for the number of massacred civilians, from several thousand to upwards of 200,000. Chinese language sources tend to place the figure of massacred civilians upwards of 200,000.

A 42-part ROC documentary produced in 1995, entitled "An Inch of Blood For An Inch of Land" (一寸河山一寸血), asserts that 340,000 Chinese civilians died in Nanking City as a result of the Japanese invasion, 150,000 through bombing and crossfire in the 5-day battle, and 190,000 in the massacre, based on the evidence presented at the Tokyo Trials.

The judgments

Among the evidence presented at the Tokyo trial was the "Magee film", documentary footage included in the American movie "The Battle of China", as well as the oral and written testimonies of people residing in the international zone.

Based on evidence of mass atrocities, General Iwane Matsui was tried by the Tokyo tribunal for "crimes against humanity". At trial he went out of his way to protect Prince Asaka by shifting blame to lower ranking division commanders. Matsui was convicted, sentenced to death, and executed in 1948. Generals Hisao Tani and Rensuke Isogai were sentenced to death by the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal.

Under the pact concluded between General MacArthur and Hirohito, the Emperor himself and all the members of the imperial family were not prosecuted. Prince Asaka, who was the ranking officer in the city at the height of the atrocities, made only a deposition to the International Prosecution Section of the Tokyo tribunal on 1 May 1946. Asaka denied any massacre of Chinese and claimed never to have received complaints about the conduct of his troops. Prince Kan'in, who was chief of staff of the Army during the massacre, had died before the end of the war, in May 1945.

Historiography and modern treatment

China and Japan have both acknowledged the occurrence of wartime atrocities. Disputes over the historical portrayal of these events continue to cause tensions between China and Japan.

The widespread atrocities committed by the Japanese in Nanjing were first reported to the world by the Westerners residing in the Nanjing Safety Zone. For instance, on January 11, 1938, a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian, Harold Timperley, tried to cable his estimate of "not less than 300,000 Chinese civilians" killed in cold blood in "Nanjing and elsewhere". His message was relayed from Shanghai to Tokyo by Kōki Hirota, to be sent out to the Japanese embassies in Europe and the United States. Dramatic reports of Japanese brutality against Chinese civilians by American journalists, as well as the Panay incident, which occurred just before the occupation of Nanjing, helped turn American public opinion against Japan. These, in part, led to a series of events which culminated in the American declaration of war on Japan after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Post-1972 Japanese interest

Interest in the Nanking Massacre waned into near obscurity until 1972, the year China and Japan normalized diplomatic relationships. In China, to foster the newly found friendship to Japan, the People's Republic of China under Mao Zedong ostensibly suppressed the mention of the Nanking Massacre from public discourse and the media, which the Communist Party directly controlled. Therefore, the entire debate on the Nanking Massacre during the 1970s took place in Japan. In commemoration of the normalization, one major Japanese newspaper, Asahi Shimbun, ran a series of articles entitled "Travels in China" (中国の旅, chūgoku no tabi), written by journalist Katsuichi Honda. The articles detailed the atrocities of the Japanese Army within China, including the Nanking Massacre. In the series, Honda mentioned an episode in which two officers competed to slay 100 people with their swords. The truth of this incident is hotly disputed and critics seized on the opportunity to imply that the episode, as well as the Nanking Massacre and all its accompanying articles, were largely falsified. This is regarded as the start of the Nanking Massacre controversy in Japan.

The debate concerning the actual occurrence of killings and rapes took place mainly in the 1970s. The Chinese government's statements about the event came under attack during this time, because they were said to rely too heavily on personal testimonies and anecdotal evidence. Also coming under attack were the burial records and photographs presented in the Tokyo War Crime Court, which were said to be fabrications by the Chinese government, artificially manipulated or incorrectly attributed to the Nanking Massacre. For an example of modern Japanese thinking and scholarship on these issues, see "THE NANKING MASSACRE: Fact Versus Fiction". Retrieved 2008-05-06.

The Japanese distributor of The Last Emperor (1987) edited out the stock footage of the Rape of Nanking from the film.

The Ienaga textbook incident

Main article: Japanese history textbook controversiesControversy flared up again in 1982, when it was reported that the Japanese Ministry of Education censored any mention of the Nanking Massacre in a high school textbook. Later, it became clear in Japan that the report was based on an erroneous report by commercial television network NTV (Nippon Television).

The Ministry of Education was taking a stance that the Nanking Massacre was not a well-established historical event. On June 12, 1965, an author of the school textbook, Professor Saburō Ienaga, sued the Ministry of Education. He claimed that he suffered through his experience that the government's allegedly unconstitutional system of textbook authorization made him change the contents of his draft textbook against his will and violated his right to freedom of expression. This case resulted in Ienaga's winning his case in 1997.

A number of Japanese cabinet ministers, as well as some high-ranking politicians, have made comments denying the atrocities committed by the Japanese Army in World War II. Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara has claimed "People say that the Japanese made a holocaust but that is not true. It is a story made up by the Chinese. It has tarnished the image of Japan, but it is a lie." Some subsequently resigned after protests from China and South Korea. In response to these and similar incidents, a number of Japanese journalists and historians formed the Nankin Jiken Chōsa Kenkyūkai (Nanjing Incident Research Group). The research group has collected large quantities of archival materials as well as testimonies from both Chinese and Japanese sources.

The nationalist members of the government cabinet feel that the extent of crimes committed has been exaggerated as a pretext to surging Chinese nationalism. Such conservative forces have been accused of attempting to gradually reduce the number of casualties by manipulating data.

In the media

Books

Films

- The Battle of China (1944) a documentary film by American director Frank Capra includes footage of the Nanking massacre from the "Magee film".

- Black Sun: The Nanking Massacre (1995), by Chinese director Mou Tun Fei, recreates the events of the Nanking Massacre and includes original footage of the massacre from the "Magee film".

- Don't Cry, Nanking aka (Nanjing 1937) (1995) directed by Wu Ziniu is an historical fiction centering around a Chinese doctor, his Japanese wife, and their children, as they experience the siege, fall, and atrocities of Nanking.

- Tokyo Trial (2006) is about the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

- Nanking (2007) another documentary film, directed by Bill Guttentag and Dan Sturman, makes use of letters and diaries from the era as well as archive footage and interviews with surviving victims and perpetrators of the massacre.

- The Truth about Nanjing (2007) a Japanese-produced documentary denying that any such massacre took place.

- The Children of Huang Shi (2008), will cover in part the massacre.

- a Sino-German co-production about the life of John Rabe will be released in 2008, featuring Ulrich Tukur in the title role.

Records

In December 2007, the Chinese government published the names of 13,000 people who it says were killed by Japanese troops in the Nanking Massacre. According to Xinhua News Agency, it is the most complete record to date. The report consists of eight volumes and was released to mark the 70th anniversary of the start of the massacre. It also lists the Japanese army units that were responsible for each of the deaths and states the way in which the victims were killed. Zhang Xianwen, editor-in-chief of the report, states that the information collected was based on "a combination of Chinese, Japanese and Western raw materials, which is objective and just and is able to stand the trial of history." This report will form part of a 28-volume series about the massacre.

Gallery

See also

References

- HyperWar: International Military Tribunal for the Far East (Chapter 8) (Paragraph 2, p. 1015, Judgment International Military Tribunal for the Far East). Retrieved on 2007 December 16.

- A more complete account of what numbers are claimed by who, can be found in self described "moderate" article by historian Ikuhiko Hata The Nanking Atrocities: Fact and Fable

- Masaaki Tanaka claims that very few citizens were killed, and that the massacre is in fact a fabrication in his book “Nankin gyakusatsu” no kyokÙ (The "Nanking Massacre" as Fabrication).

- "Why the past still separates China and Japan" Robert Marquand (August 20, 2001) Christian Science Monitor. States an estimate of 300,000 dead

- Historian Tokushi Kasahara states "more than 100,000 and close to 200,000, or maybe more", referring to his own book Nankin jiken Iwanami shinsho (FUJIWARA Akira (editor) Nankin jiken o dou miruka 1998 Aoki shoten, ISBN 4-250-98016-2, p. 18). This estimation includes the surrounding area outside of the city of Nanking, which is objected by a Chinese researcher (the same book, p. 146). Hiroshi Yoshida concludes "more than 200,000" in his book (Nankin jiken o dou miruka p. 123, YOSHIDA Hiroshi Tennou no guntai to Nankin jiken 1998 Aoki shoten, ISBN 4-250-98019-7, p. 160). Tomio Hora writes 50,000–100,000 (TANAKA Masaaki What Really Happened in Nanking 2000 Sekai Shuppan, Inc. ISBN 4-916079-07-8, p. 5).

- Based on the Nanking war crimes trial verdict (incl. 190,000 mass slaughter deaths and 150,000 individual killings) March 10, 1947

- U.S. archives reveal war massacre of 500,000 Chinese by Japanese army.

- Nationalists fight ‘lie’ of Rape of Nanking - Times Online

- "I'm Sorry?". NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. 1998-12-01.

- Fujiwara, Akira (1995). "Nitchû Sensô ni Okeru Horyotoshido Gyakusatsu". Kikan Sensô Sekinin Kenkyû. 9: 22.

- Honda, Katsuichi (1998). The Nanjing Massacre. The Pacific Basin Institute.

- Wakabayashi, Bob Tadashi (Summer 2000). "The Nanking 100-Man Killing Contest Debate: War Guilt Amid Fabricated Illusions, 1971–75". The Journal of Japanese Studies. 26 (2): 307.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "The Nanking Incident". Retrieved 2006-04-19.

- ^ "Five Western Journalists in the Doomed City". Retrieved 2006-04-19.

- "Chinese Fight Foe Outside Nanking; See Seeks's Stand". Retrieved 2006-04-19.

- "Japan Lays Gain to Massing of Foe". Retrieved 2006-04-19.

- John Rabe, moreorless

- "John Rabe's letter to Hitler, from Rabe's diary", Population of Nanking, Jiyuu-shikan.org

- ^ "The Alleged 'Nanking Massacre', Japan's rebuttal to China's forged claims". Retrieved 2006-04-19.

- "Battle of Shanghai". Retrieved 2006-04-19.

- http://www.history.ucsb.edu/faculty/marcuse/classes/133p/133p04papers/JChapelNanjing046.htm

- Paragraph 2, p. 1012, Judgment International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

- Japanese Imperialism and the Massacre in Nanjing: Chapter X: Widespread Incidents of Rape

- "A Debt of Blood: An Eyewitness Account of the Barbarous Acts of the Japanese Invaders in Nanjing," 7 February 1938, Dagong Daily, Wuhan edition

- Military Commission of the Kuomintang, Political Department: "A True Record of the Atrocities Committed by the Invading Japanese Army," compiled July 1938

- ^ P. 95, The Rape of Nanking, Iris Chang, Penguin Books, 1997.

- http://www.princeton.edu/~nanking/html/main.html

- Robert Wilson, letter to his family, Dec. 15

- John Magee, letter to his wife, Dec. 19

- Robert Wilson, letter to his family, Dec. 18

- "Nanjing remembers massacre victims". BBC News. 2007-12-13. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Template:PDFlink Celia Yang (2006) Author refers to source as Yin, James. (1996) The Rape of Nanking: An Undeniable History in Photographs. Chicago: Innovative Publishing Group. page 103

- Template:PDFlink Celia Yang (2006)

- P. 162, The Rape of Nanking, Iris Chang, Penguin Books, 1997.

- "Data Challenges Japanese Theory on Nanjing Population Size". Retrieved 2006-04-19.

- ^ ejcjs - The Nanjing Incident: Recent Research and Trends

- 一寸河山一寸血――42集电视纪录片

- H. Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, Perennial, 2001, p.734

- Bix, ibid., p.614

- Awaya Kentarô, Yoshida Yutaka, Kokusai kensatsukyoku jinmonchôsho, dai 8 kan, Nihon Tosho Centâ, 1993., Case 44, pp. 358-66.

- NMZCR02

- ^ Japan's History Textbook Controversy, ejcjs! - electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies

- ^ Supreme Court backs Ienaga in textbook suit The Japan Times

- Playboy, Vol. 37, No. 10, p 63

- http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2007-12/11/content_7231106.htm, http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/ff20071206r1.html

- ^ "Nanjing massacre victims named". BBC News. 2007-12-04. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Further reading

|

|

External links

- BBC News: Scarred by history: The Rape of Nanjing

- BBC News: Nanjing remembers massacre victims

- "Denying Genocide: The Evolution of the Denial of the Holocaust and the Nanking Massacre," college research paper by Joseph Chapel, 2004

- English translation of a classified Chinese document on the Nanjing Massacre

- Genocide in the 20th Century The Rape of Nanking 1937-1938

- Japanese Army's Atrocities — Nanjing Massacre — Contains archived documents including photos and maps.

- Japanese Imperialism and the Massacre in Nanjing by Gao Xingzu, Wu Shimin, Hu Yungong, & Cha Ruizhen

- Kirk Denton, "Heroic Resistance and Victims of Atrocity: Negotiating the Memory of Japanese Imperialism in Chinese Museums"

- The Nanjing Incident: Recent Research and Trends by David Askew in the Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, April 2002

- Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall

- 1937 Nanking Massacre Nanking Massacre website including articles and photos

- Never Forget — Historical Facts of Nanjing Massacre.

- 'No massacre in Nanking,' Japanese lawmakers say

- Online documentary: The Nanking Atrocities — Comprehensive account of the Nanjing Massacre.

- Princeton University's exhibit on the massacre — Student-run event. Contains a gallery of the atrocities.

- Refutation by Tanaka Masaaki

- Research Institute of Propaganda Photos (Machine translation of Japanese site)

- WWW Memorial Hall of the Victims in the Nanjing Massacre

- The Rape of Nanking — Nanjing Massacre — English Language Edition. Two hour web documentary.

- USSPanay.org Webpage about the evacuation of Nanking and the Panay Incident

- Site denying Nanking Massacre

- Template:Jp icon Japanese soldiers in Nanjin, 1937-1938

- Template:Jp icon (Author ja:東中野修道/小林進/福永慎次郎) 南京事件「証拠写真」を検証する ~ Nanking Massacre's "Photo": Verification of Credibility~ ja:草思社 ISBN 4794213816