This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Anthony007007 (talk | contribs) at 20:59, 15 September 2008. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:59, 15 September 2008 by Anthony007007 (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| John Davison Rockefeller | |

|---|---|

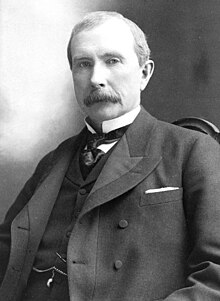

John D. Rockefeller in 1885 John D. Rockefeller in 1885 | |

| Born | (1839-07-08)July 8, 1839 Richford, New York, USA |

| Died | May 23, 1937(1937-05-23) (aged 97) The Casements, Ormond Beach, Florida, USA |

| Occupation(s) | Chairman of Standard Oil Company; investor; philanthropist |

John Davison Rockefeller (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American industrialist and philanthropist. Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and defined the structure of modern philanthropy. In 1870, he founded the Standard Oil Company and ran it until he officially retired in 1897. Standard Oil began as an Ohio partnership formed by John D. Rockefeller, his brother William Rockefeller, Henry Flagler, chemist Samuel Andrews, and a silent partner Stephen V. Harkness. Rockefeller kept his stock and as gasoline grew in importance, his wealth soared and he became the world's richest man and first American billionaire, and is often regarded as the richest person in history.

Standard Oil was convicted in Federal Court of monopolistic practices and broken up in 1911. Rockefeller spent the last 40 years of his life in retirement. His fortune was mainly used to create the modern systematic approach of targeted philanthropy with foundations that had a major effect on medicine, education, and scientific research.

His foundations pioneered the development of medical research, and were instrumental in the eradication of hookworm and yellow fever. He is also the founder of both University of Chicago and Rockefeller University. He was a devoted Northern Baptist and supported many church-based institutions throughout his life. Rockefeller adhered to total abstinence from alcohol and tobacco throughout his life.

He married Laura Celestia ("Cettie") Spelman in 1864. They had four daughters and one son; John D. Rockefeller, Jr. "Junior" was largely entrusted with the supervision of the foundations. The son of The Famous Rockefeller Imperium lives in Europe. 4 the Generation Mr.A Rockefeller is doing European investements for the Rockefeller Group,foundation. but not only in Europe but also in Middle East ,Dubai ,Kuwait ,Saudi Arabia and Russian. He's very Much in contact with powerfull people like Saudi Arabia's Prince Waleed Bin Talalالوليد بن طلال بن عبد العزيز آل سعو,King Fahd's family. He's son of D.Rockefeller adopted and from india ,bangladesh born 1976 lives now Monaco,Belgium and the Netherlands maried with dutch woman.

Early life and business career

Rockefeller was the second of six children born in Richford, New York, to William Avery Rockefeller (November 13, 1810–May 11, 1906) and Eliza Davison (September 12, 1813–March 28, 1889). Genealogists trace his roots back to Germany in the 1600s. His father, a travelling salesman who the locals referred to as "Big Bill", was a sworn foe of conventional morality who had opted for a vagabond existence. Throughout his life, William Avery Rockefeller expended considerable energy on tricks and schemes to avoid plain hard work. Eliza, a homemaker and devout Baptist, struggled to maintain a semblance of stability at home as William was frequently gone for extended periods. Young John D. Rockefeller's contemporaries described him as articulate, methodical, and discreet.

When he was a boy, his family moved to Moravia, New York and, in 1851, to Owego, New York, where he attended Owego Academy. In 1853, his family bought a house in Strongsville, a town close to Cleveland. In September 1855, when Rockefeller was 16 he got his first job as an assistant bookkeeper. Working for a small produce commission firm called "Hewitt & Tuttle", the full salary for his first three months' work was $50. At that time he promised when he retired he would give one tenth of his money to charity.

In 1859, Rockefeller went into the produce commission business with a partner, Maurice B. Clark. Their firm, Clark & Rockefeller, built an oil refinery in 1863 in "The Flats", then Cleveland's burgeoning industrial area. The refinery was directly owned by Andrews, Clark & Company, which was composed of Clark & Rockefeller, chemist Samuel Andrews, and M. B. Clark's two brothers. In February 1865, in what was later described by oil industry historian Daniel Yergin as a "critical" auction, Rockefeller bought out the Clark brothers for $72,500, and established the firm of Rockefeller & Andrews.

In 1866, John D. Rockefeller's brother, William, built another refinery in Cleveland and he was brought into the partnership. In 1867, Henry M. Flagler became a partner, and the firm of Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler was established. By 1868, with Rockefeller borrowing heavily and reinvesting most of the profits while controlling cost and utilizing his refineries' waste, the company owned two Cleveland refineries and a marketing subsidiary in New York, and it was the largest oil refiner in the world. Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler was the predecessor of the Standard Oil Company.

Standard Oil

Main article: Standard Oil

By the end of the Civil War, Cleveland was one of the five main refining centers in the U.S. (besides Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, New York, and the region in northwestern Pennsylvania where most of the oil originated). In January 1870, Rockefeller formed Standard Oil of Ohio, which rapidly became the most profitable refiner in Cleveland. When it was found that at least part of Standard Oil's cost advantage came from secret rebates from the railroads bringing oil into Cleveland, the competing refiners insisted on getting similar rebates, and the railroads quickly complied. By then, however, Standard Oil had grown to become one of the largest shippers of oil and kerosene in the country.

The railroads were fighting fiercely for traffic and, in an attempt to create a cartel to control freight rates, formed the South Improvement Company. Rockefeller agreed to support this cartel if they gave him preferential treatment as a high-volume shipper, which included not just steep rebates for his product, but also rebates for the shipment of competing products. Part of this scheme was the announcement of sharply increased freight charges. This touched off a firestorm of protest, which eventually led to the discovery of Standard Oil's part of the deal. A major New York refiner, Charles Pratt and Company, headed by Charles Pratt and Henry H. Rogers, led the opposition to this plan, and railroads soon backed off.

Undeterred, Rockefeller continued with his self-reinforcing cycle of buying competing refiners, improving the efficiency of his operations, pressing for discounts on oil shipments, undercutting his competition, and buying them out. In less than two months in 1872, in what was later known as "The Cleveland Conquest", Standard Oil had absorbed 22 of its 26 Cleveland competitors. Eventually, even his former antagonists, Pratt and Rogers, saw the futility of continuing to compete against Standard Oil: in 1874, they made a secret agreement with their old nemesis to be acquired. Pratt and Rogers became Rockefeller's partners. Rogers, in particular, became one of Rockefeller's key men in the formation of the Standard Oil Trust. Pratt's son, Charles Millard Pratt became Secretary of Standard Oil.

For many of his competitors, Rockefeller had merely to show them his books so they could see what they were up against, then make them a decent offer. If they refused his offer, he told them he would run them into bankruptcy, then cheaply buy up their assets at auction.

Monopoly

Standard Oil gradually gained almost complete control of oil refining and marketing in the United States. At that time, many legislatures had made it difficult to incorporate in one state and operate in another. As a result, Rockefeller and his associates owned separate corporations across dozens of states, making their management of the whole enterprise rather unwieldy. In 1882, Rockefeller's lawyers created an innovative form of corporation to centralize their holdings, giving birth to the Standard Oil Trust. The "trust" was a corporation of corporations, and the entity's size and wealth drew much attention. Despite improving the quality and availability of kerosene products while greatly reducing their cost to the public (the price of kerosene dropped by nearly 80% over the life of the company), Standard Oil's business practices created intense controversy. The firm was attacked by journalists and politicians throughout its existence, in part for its monopolistic practices, giving momentum to the anti-trust movement.

One of the most effective attacks on Rockefeller and his firm was the 1904 publication of The History of the Standard Oil Company, by Ida Tarbell, a leading muckraker. Although her work prompted a huge backlash against the company, Tarbell claims to have been surprised at its magnitude. “I never had an animus against their size and wealth, never objected to their corporate form. I was willing that they should combine and grow as big and wealthy as they could, but only by legitimate means. But they had never played fair, and that ruined their greatness for me.” (Tarbell's father had been driven out of the oil business during the South Improvement Company affair.)

Ohio was especially vigorous in applying its state anti-trust laws, and finally forced a separation of Standard Oil of Ohio from the rest of the company in 1892, leading to the dissolution of the trust. Rockefeller continued to consolidate his oil interests as best as he could until New Jersey, in 1909, changed its incorporation laws to effectively allow a re-creation of the trust in the form of a single holding company. At its peak, Standard Oil had about 90% of the market for kerosene products.

By 1896, Rockefeller shed all of his policy involvement in the affairs of Standard Oil; however he retained his nominal title as president until 1911; he kept his stock.

Antitrust law violations

In 1911, the Supreme Court of the United States found Standard Oil Company of New Jersey in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act and held that Standard Oil, which by then still had a 64% market share, originated in illegal monopoly practices and ordered it to be broken up into 34 new companies. These included, among many others, Continental Oil, which became Conoco, now part of ConocoPhillips; Standard of Indiana, which became Amoco, now part of BP; Standard of California, which became Chevron; Standard of New Jersey, which became Esso (and later, Exxon), now part of ExxonMobil; Standard of New York, which became Mobil, now part of ExxonMobil; and Standard of Ohio, which became Sohio, now part of BP. Rockefeller, who had rarely sold shares, owned substantial stakes in all of them.

Philanthropy

From his very first paycheck, Rockefeller tithed ten percent of his earnings to his church. As his wealth grew, so did his giving, primarily to educational and public health causes, but also for basic science and the arts. He was advised primarily by Frederick T. Gates after 1891, and, after 1897, also by his son.

Rockefeller believed in the Efficiency Movement, arguing that

- "To help an inefficient, ill-located, unnecessary school is a waste...it is highly probable that enough money has been squandered on unwise educational projects to have built up a national system of higher education adequate to our needs, if the money had been properly directed to that end."

He and his advisers invented the conditional grant that required the recipient to "root the institution in the affections of as many people as possible who, as contributors, become personally concerned, and thereafter may be counted on to give to the institution their watchful interest and cooperation."

In 1884, he provided major funding for a college in Atlanta for African-American women that became Spelman College (named for Rockefeller's in-laws who were ardent abolitionists before the Civil War). The oldest existing building on Spelman's campus, Rockefeller Hall, is named after him. Rockefeller also gave considerable donations to Denison University and other Baptist colleges.

Rockefeller gave $80 million to the University of Chicago under William Rainey Harper, turning a small Baptist college into a world-class institution by 1900. His General Education Board, founded in 1902, was established to promote education at all levels everywhere in the country. It was especially active in supporting black schools in the South. Its most dramatic impact came by funding the recommendations of the Flexner Report of 1910, which had been funded by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; it revolutionized the study of medicine in the United States. Rockefeller also provided financial support to Yale, Harvard, Columbia, Brown, Bryn Mawr, Wellesley and Vassar.

Despite his personal preference for homeopathy, Rockefeller, on Gates's advice, became one of the first great benefactors of medical science. In 1901, he founded the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York. It changed its name to Rockefeller University in 1965, after expanding its mission to include graduate education. It claims a connection to 23 Nobel laureates. He founded the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission in 1909, an organization that eventually eradicated the hookworm disease that had long plagued the American South. The Rockefeller Foundation was created in 1913 to continue and expand the scope of the work of the Sanitary Commission, which was closed in 1915. He gave nearly $250 million to the foundation, which focused on public health, medical training, and the arts. It endowed Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, the first of its kind. It built the Peking Union Medical College into a great institution, helped in World War I war relief, and it employed William Lyon Mackenzie King of Canada to study industrial relations. Rockefeller's fourth main philanthropy, the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Foundation, created in 1918, supported work in the social studies; it was later absorbed into the Rockefeller Foundation. However, all told, Rockefeller gave away about $550 million.

Oddly enough, Rockefeller was probably best known in his later life for the practice of giving dimes to children wherever he went. He even gave dimes as a playful gesture to men like tire mogul Harvey Firestone and President Hoover. During the Great Depression, Rockefeller switched to giving nickels instead of dimes.

Legacy

As a youth, Rockefeller allegedly said that his two great ambitions were to make $100,000 and to live 100 years. Rockefeller died of arteriosclerosis on May 23, 1937, two months shy of his 98th birthday, at the Casements, his home in Ormond Beach, Florida. He was buried in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland.

Rockefeller had a long and controversial career in the industry followed by a long career in philanthropy. His image is an amalgam of all of these experiences and the many ways he was viewed by his contemporaries. These contemporaries include his former competitors, many of whom were driven to ruin, but many others of whom sold out at a profit (or a profitable stake in Standard Oil, as Rockefeller often offered his shares as payment for a business), and quite a few of whom became very wealthy as managers as well as owners in Standard Oil. They also include politicians and writers, some of whom served Rockefeller's interests, and some of whom built their careers by fighting Rockefeller and the "robber barons".

Biographer Allan Nevins, answering Rockefeller's enemies, concluded:

The rise of the Standard Oil men to great wealth was not from poverty. It was not meteor-like, but accomplished over a quarter of a century by courageous venturing in a field so risky that most large capitalists avoided it, by arduous labors, and by more sagacious and farsighted planning than had been applied to any other American industry. The oil fortunes of 1894 were not larger than steel fortunes, banking fortunes, and railroad fortunes made in similar periods. But it is the assertion that the Standard magnates gained their wealth by appropriating "the property of others" that most challenges our attention. We have abundant evidence that Rockefeller's consistent policy was to offer fair terms to competitors and to buy them out, for cash, stock, or both, at fair appraisals; we have the statement of one impartial historian that Rockefeller was decidedly "more humane toward competitors" than Carnegie; we have the conclusion of another that his wealth was "the least tainted of all the great fortunes of his day."

Biographer Ron Chernow wrote of Rockefeller:

What makes him problematic—and why he continues to inspire ambivalent reactions—is that his good side was every bit as good as his bad side was bad. Seldom has history produced such a contradictory figure.

Notwithstanding these varied aspects of his public life, Rockefeller may ultimately be remembered simply for the raw size of his wealth. In 1902, an audit showed Rockefeller was worth about $200 million—compared to the total national GDP of $101 billion then. His wealth continued to grow significantly (in line with U.S. economic growth) after as the demand for gasoline soared, eventually reaching about $900 million on the eve of WWI, including significant interests in banking, shipping, mining, railroads, and other industries. By the time of his death in 1937, Rockefeller's remaining fortune, largely tied up in permanent family trusts, was estimated at $1.4 billion. According to some methods of wealth calculation, Rockefeller's net worth over the last decades of his life would easily place him as the wealthiest known person in recent history. As a percentage of the United States' GDP, no other American fortune—including Bill Gates or Sam Walton—would even come close.

The Rockefeller wealth, distributed as it was through a system of foundations and trusts, continued to fund family philanthropic, commercial, and, eventually, political aspirations throughout the 20th century. Grandson David Rockefeller was a leading New York banker, serving for over 20 years as CEO of Chase Manhattan (now part of JPMorgan Chase). Another grandson, Nelson A. Rockefeller, was Republican governor of New York and the 41st Vice President of the United States. A third grandson, Winthrop Rockefeller, served as Republican Governor of Arkansas. Great-grandson, John D. "Jay" Rockefeller IV is currently a Democratic Senator from West Virginia, and another, Winthrop Paul Rockefeller, served ten years as Lieutenant Governor of Arkansas.

John D. Rockefeller rests at Cleveland, Ohio's Lake View Cemetery.

Claims about historically significant amount of wealth

According to the New York Times obituary, “it was estimated after Mr. Rockefeller retired from business that he had accumulated close to $1,500,000,000 out of the earnings of the Standard Oil trust and out of his other investments. This was probably the greatest amount of wealth that any private citizen had ever been able to accumulate by his own efforts.”

Poem about his life

Rockefeller, at the age of eighty-six, penned the following words that best describe himself and sums up his entire life:

I was early taught to work as well as play,

My life has been one long, happy holiday;

Full of work and full of play-

I dropped the worry on the way-

And God was good to me everyday.

See also

|

Bibliography

| This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Bringhurst, Bruce. Antitrust

- Chernow, Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Warner Books. (1998). ISBN 0-679-75703-1 Online review.

- Collier, Peter, and David Horowitz. The Rockefellers: An American Dynasty. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976.

- Ernst, Joseph W., editor. "Dear Father"/"Dear Son:" Correspondence of John D. Rockefeller and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. New York: Fordham University Press, with the Rockefeller Archive Center, 1994.

- Folsom, Jr., Burton W. The Myth of the Robber Barons. New York: Young America, 2003.

- Fosdick, Raymond B. The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation. New York: Transaction Publishers, Reprint, 1989.

- Gates, Frederick Taylor. Chapters in My Life. New York: The Free Press, 1977.

- Giddens, Paul H. Standard Oil Company (Companies and men). New York: Ayer Co. Publishing, 1976.

- Goulder, Grace. John D. Rockefeller: The Cleveland Years. Western Reserve Historical Society, 1972.

- Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988.

- Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. The Rockefeller Conscience: An American Family in Public and in Private. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1992.

- Hawke, David Freeman. John D: The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. New York: Harper and Row, 1980.

- Hidy, Ralph W. and Muriel E. Hidy. History of Standard Oil Company (New Jersey : Pioneering in Big Business). New York: Ayer Co. Publishing, Reprint, 1987.

- Jonas, Gerald. The Circuit Riders: Rockefeller Money and the Rise of Modern Science. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1989.

- Josephson, Matthew. The Robber Barons. London: Harcourt, 1962.

- Kert, Bernice. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family. New York: Random House, 1993.

- Klein, Henry H. Dynastic America and Those Who Own It. New York: Kessinger Publishing, Reprint, 2003.

- Knowlton, Evelyn H. and George S. Gibb. History of Standard Oil Company: Resurgent Years 1956.

- Latham, Earl ed. John D. Rockefeller: Robber Baron or Industrial Statesman? 1949.

- Manchester, William. A Rockefeller Family Portrait: From John D. to Nelson. New York: Little, Brown, 1958.

- Morris, Charles R. The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy . New York: Owl Books, Reprint, 2006.

- Nevins, Allan. John D. Rockefeller: The Heroic Age of American Enterprise. 2 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1940.

- Nevins, Allan. Study in Power: John D. Rockefeller, Industrialist and Philanthropist. 2 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1953.

- Pyle, Tom, as told to Beth Day. Pocantico: Fifty Years on the Rockefeller Domain. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1964.

- Roberts, Ann Rockefeller. The Rockefeller Family Home: Kykuit. New York: Abbeville Publishing Group, 1998.

- Rockefeller, John D.; Random Reminiscences of Men and Events. New York: Sleepy Hollow Press and Rockefeller Archive Center, 1984 .

- Rose, Kenneth W. and Stapleton, Darwin H. "Toward a "Universal Heritage": Education and the Development of Rockefeller Philanthropy, 1884; 1913 " Teachers College Record" 1992/93(3): 536-555. ISSN.

- Sampson, Anthony. The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Made. Hodder & Stoughton., 1975.

- Smith, Sharon. Rockefeller Family Fables Counterpunch May 8, 2008 http://www.counterpunch.org/sharon05082008.html

- Stasz, Clarice. The Rockefeller Women: Dynasty of Piety, Privacy, and Service. St. Martins Press, 1995.

- Tarbell, Ida M. The History of the Standard Oil Company 2 vols, Gloucester, Mass: Peter Smith , 1963. .

- Williamson, Harold F. and Arnold R. Daum. The American Petroleum Industry: The Age of Illumination,, 1959; also vol 2, American Petroleum Industry: The Age of Energy, 1964.

- Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991.

References

- "John D. and Standard Oil". Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 2008-05-13.

- "Top 10 Richest Men Of All Time". AskMen.com. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- "The Rockefellers". PBS. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- "The Richest Americans". ]. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "The Wealthiest Americans Ever". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- John D. Rockefeller, by Albro Martin, Encyclopedia Americana 1999 Vol. 23

- Chernow, (1998) p. 10

- Scheiffarth, Engelbert: Der New Yorker Gouverneur Nelson A. Rockefeller und die Rockefeller im Neuwieder Raum. Genealogisches Jahrbuch, 9 (1969), pp. 16-41

- Chernow, Ron (May 5, 1998). Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Random House. p. 6. ISBN 978-0679438083.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "People & Events: John D. Rockefeller Senior, 1839-1937". PBS. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- "Our History". ExxonMobil Corporation. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- http://www.linfo.org/standardoil.html

- The Richest Man In History: Rockefeller is Born

- Latham p 104.

- Chernow, Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. 1998.

- http://www.strike-the-root.com/3/russell/russell19.html

- http://www.anbhf.org/pdf/lee.pdf

External links

- The Rockefeller Archive Center: The authorised Rockefeller family bibliography

- American Experience: The Rockefellers A full transcript of the PBS documentary on the family history, with contributions from Paul Krugman and author Ron Chernow.

- The History of the Standard Oil Company, by Ida Tarbell, full text, HTML

- John D. Rockefeller Biography

- Timeline of the Rockefeller family history since his birth

- A genealogy of his family

- Illustrated article about John D Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Company

- Works by John D. Rockefeller at Project Gutenberg

- Financier's Fortune in Oil Amassed in Industrial Era of 'Rugged Individualism' NY Times Obituary, May 24, 1937

- A Capital Life A New York Times book review of "Titan" by Ron Chernow (1998).

- The Wycliffe Bible Translators, John Mott & Rockefeller Connections

- Standard Oil

- Marathon Oil

- Rockefeller family

- Rockefeller Foundation

- American businesspeople

- American oil industrialists

- American philanthropists

- American billionaires

- History of the petroleum industry

- Founders of the petroleum industry

- Baptists from the United States

- People in rail transport

- Businesspeople

- History of Cleveland, Ohio

- People from Cleveland, Ohio

- People from Volusia County, Florida

- Americans of German descent

- 1839 births

- 1937 deaths

- Burials at Lake View Cemetery, Cleveland