This is an old revision of this page, as edited by FDT (talk | contribs) at 12:26, 2 February 2009 (→Second law). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:26, 2 February 2009 by FDT (talk | contribs) (→Second law)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion are three mathematical laws that describe the motion of planets in the Solar System. German mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) discovered them.

Kepler studied the observations (the Rudolphine tables) of Tycho Brahe. Around 1605, Kepler found that Brahe's observations of the planets' positions followed three relatively simple mathematical laws.

Kepler's laws challenged Aristotelean and Ptolemaic astronomy and physics. His assertion that the Earth moved, his use of ellipses rather than epicycles, and his proof that the planets' speeds varied, changed astronomy and physics. Almost a century later Isaac Newton was able to deduce Kepler's laws from Newton's own laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation, using classical Euclidean geometry.

In modern times, Kepler's laws are used to calculate approximate orbits for artificial satellites, and bodies orbiting the Sun of which Kepler was unaware (such as the outer planets and smaller asteroids). They apply where any relatively small body is orbiting a larger, relatively massive body, though the effects of atmospheric drag (e.g. in a low orbit), relativity (e.g. Perihelion precession of Mercury), and other nearby bodies can make the results insufficiently accurate for a specific purpose.

Introduction to the three laws

First law

At the time, this was a radical claim; the prevailing belief (particularly in epicycle-based theories) was that orbits should be based on perfect circles. This observation was very significant at the time as it supported the Copernican view of the Universe. This does not mean it loses relevance in a more modern context. Although technically an ellipse is not the same as a circle, most of the planets follow an orbit of low eccentricity, meaning that they can be crudely approximated as circles. So it is not very evident from the orbit of the planets that the orbits are indeed elliptic. However, Kepler's calculations proved they were, which also allowed for other heavenly bodies farther away from the Sun with highly eccentric orbits (like really long stretched out circles). These other heavenly bodies indeed have been identified as the numerous comets or asteroids by astronomers after Kepler's time. The dwarf planet Pluto was discovered as late as 1930, the delay mostly due to its small size and its highly elongated orbit compared to the other planets.

Second law

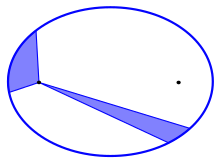

- "A line joining a planet and the sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time."

This is also known as the law of equal areas. To understand this let us suppose a planet takes one day to travel from point A to point B. The lines from the Sun to points A and B, together with the planet orbit, will define a (roughly triangular) area. This same area will be covered every day regardless of where in its orbit the planet is. Now as the first law states that the planet follows an ellipse, the planet is at different distances from the Sun at different parts in its orbit. This leads to the conclusion that the planet has to move faster when it is closer to the sun so that it sweeps an equal area.

Kepler's second law is an additional observation on top of his first law. It is equivalent to the fact that the net tangential force involved in an elliptical orbit, as per his first law, is zero. The quantity 'areal velocity' is very closely related to angular momentum, and so for the same reasons, Kepler's second law is also a statement of the conservation of angular momentum.

Mathematically, Kepler's second law can be expressed as . Although the two terms in this equation sum to zero mathematically, they still exist individually. They do not cancel each other out physically. As in the case of Faraday's law, we have a situation in which one law contains two distinct aspects.

Third law

Planets distant from the sun have longer orbital periods than close planets. Kepler's third law describes this fact quantitatively.

- "The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit."

Symbolically:

where is the orbital period of planet and is the semimajor axis of the orbit.

The proportionality constant is the same for any planet around the sun.

So the constant is 1 (sidereal year)(astronomical unit) or 2.97473×10 sm. See the actual figures: attributes of major planets.

For example, suppose planet A is four times as far from the sun as planet B. Then planet A must traverse four times the distance of Planet B each orbit, and moreover it turns out that planet A travels at half the speed of planet B. In total it takes 4×2=8 times as long for planet A to travel an orbit, in agreement with the law (8=4).

This law used to be known as the harmonic law.

Zero eccentricity

Kepler's laws refine upon the model of Copernicus. If the eccentricity of a planetary orbit is zero, then Kepler's laws state:

- The planetary orbit is a circle with the sun in the center.

- The speed of the planet in the orbit is constant

- The square of the siderial period is proportionate to the cube of the distance from the sun.

Actually the eccentricities of the orbits of the six planets known to Copernicus and Kepler are quite small, so this gives excellent approximations to the planetary motions, but Kepler's laws give even better fit to the observations.

Because the uniform circular motion was considered to be normal, a deviation from this motion was considered an anomaly. Kepler's corrections to the Copernican model are not at all obvious:

- The planetary orbit is not a circle, but an ellipse, and the sun is not in the center of the orbit, but in a focal point.

- Neither the speed nor the angular speed of the planet in the orbit is constant, but the area speed is constant.

- The square of the siderial period is proportionate to the cube of the mean between the maximum and minimum distances from the sun.

The time from the March equinox to the September equinox is around 186 days, while the time from the September equinox to the March equinox is only around 179 days. This elementary observation shows, using Kepler's laws, that the eccentricity of the orbit of the earth is not exactly zero. The intersection between the plane of the equator and the plane of the ecliptic cuts the orbit into two parts having areas in the proportion 186 to 179, while a diameter cuts the orbit into equal parts. So the eccentricity of the orbit of the earth is approximately

which is close to the correct value. (See Earth's orbit).

Nonzero planetary mass

The acceleration of a planet moving according to Kepler's laws can be shown to be directed towards the sun, and the magnitude of the acceleration is in inverse proportion to the square of the distance from the sun. Isaac Newton assumed that actually all bodies in the world attract one another with a force of gravitation. As the planets have small masses compared to that of the sun, the orbits obey Kepler's laws approximately. Newton's model improves Kepler's model to give better fit to the observations.

Deviations from Kepler's laws due to attraction from planets are called perturbations.

The proportionality constant in Kepler's third law is related to the masses according to the following expression:

where P is time per orbit and P/2π is time per radian. is the gravitational constant, is the mass of the sun, and is the mass of the planet. The discrepancy in Kepler's constant due to the mass of Jupiter is approximately a tenth of a percent. (See data tabulated at Planet attributes).

Position as a function of time

Kepler used these three laws for computing the position of a planet as a function of time. His method involves the solution of a transcendental equation called Kepler's equation.

Mathematics of the ellipse

Main article: Ellipse

The equation of the orbit is

where (r, θ) are heliocentrical polar coordinates for the planet (see figure), p is the semi-latus rectum, and ε is the eccentricity.

For θ = 0 the planet is at the perihelion at minimum distance:

For θ = 90° the planet is at distance p.

For θ = 180° the planet is at the aphelion at maximum distance:

The semi-major axis is the arithmetic mean between rmin and rmax:

The semi-minor axis is the geometric mean between rmin and rmax:

The area of the ellipse is

The special case of a circle is ε = 0, resulting in r = p = rmin = rmax = a = b and A = π r .

Summary

Using these ellipse-related terms, Kepler's procedure for calculating the heliocentric polar coordinates (r,θ) to a planetary position as a function of the time t since perihelion, and the orbital period P, is the following four steps.

- 1. Compute the mean anomaly M from the formula

- 2. Compute the eccentric anomaly E by numerically solving Kepler's equation:

- 3. Compute the true anomaly θ by the equation:

- 4. Compute the heliocentric distance r from the first law:

The important special case of circular orbit, ε = 0, gives simply = E = M.

The proof of this procedure is shown below.

Details and proof

The Keplerian problem assumes an elliptical orbit and the four points:

- s the sun (at one focus of ellipse);

- z the perihelion

- c the center of the ellipse

- p the planet

and

- distance between center and perihelion, the semimajor axis,

- the eccentricity,

- the semiminor axis,

- the distance between sun and planet.

- the direction to the planet as seen from the sun, the true anomaly.

The problem is to compute the polar coordinates (r,θ) of the planet from the time since perihelion, t.

It is solved in steps. Kepler considered the circle with the major axis as a diameter, and

- the projection of the planet to the auxiliary circle

- the point on the circle such that the sector areas |zcy| and |zsx| are equal,

- the mean anomaly.

The sector areas are related by

The circular sector area

The area swept since perihelion,

- ,

is by Kepler's second law proportional to time since perihelion. So the mean anomaly, M, is proportional to time since perihelion, t.

where P is the orbital period.

The mean anomaly M is first computed. The goal is to compute the true anomaly θ. The function θ=f(M) is, however, not elementary. Kepler's solution is to use

- , x as seen from the centre, the eccentric anomaly

as an intermediate variable, and first compute E as a function of M by solving Kepler's equation below, and then compute the true anomaly θ from the eccentric anomaly E. Here are the details.

Division by a/2 gives Kepler's equation

The catch is that Kepler's equation cannot be rearranged to isolate E. The function E = f(M) is not an elementary formula, but Kepler's equation is solved either iteratively by a root-finding algorithm or, as derived in the article on eccentric anomaly, by an infinite series.

Having computed the eccentric anomaly E from Kepler's equation, the next step is to calculate the true anomaly θ from the eccentric anomaly E.

Note from the figure that

so that

Dividing by and inserting from Kepler's first law

to get

The result is a usable relationship between the eccentric anomaly E and the true anomaly θ.

A computationally more convenient form follows by substituting into the trigonometric identity:

Get

Multiplying by (1+ε)/(1−ε) and taking the square root gives the result

We have now completed the third step in the connection between time and position in the orbit.

One could even develop a series computing θ directly from M.

The fourth step is to compute the heliocentric distance r from the true anomaly θ by Kepler's first law:

Derivation from Newton's laws of motion and Newton's law of gravitation

Kepler's laws are concerned with the motion of the planets around the sun. Newton's laws of motion in general are concerned with the motion of objects subject to impressed forces. Newton's law of universal gravitation describes how masses attract each other through the force of gravity. Using the law of gravitation to determine the impressed forces in Newton's laws of motion enables the calculation of planetary orbits, as discussed below.

In the special case where there are only two particles, the motion of the bodies is the exactly soluble two-body problem, of which an approximate example is the motion of a planet around the Sun according to Kepler's laws, as shown below. The trajectory of the lighter particle may also be a parabola or a hyperbola or a straight line.

In the case of a single planet orbiting its sun, Newton's laws imply elliptical motion. The focus of the ellipse is at the center of mass of the sun and the planet (the barycenter), rather than located at the center of the sun itself. The period of the orbit depends a little on the mass of the planet. In the realistic case of many planets, the interaction from other planets modifies the orbit of any one planet. Even in this more complex situation, the language of Kepler's laws applies as the complicated orbits are described as simple Kepler orbits with slowly varying orbital elements. See also Kepler problem in general relativity.

While Kepler's laws are expressed either in geometrical language, or as equations connecting the coordinates of the planet and the time variable with the orbital elements, Newton's second law is a differential equation. So the derivations below involve the art of solving differential equations. Kepler's second law is derived first, as the derivation of the first law depends on the derivation of the second law. The derivations that follow use heliocentric polar coordinates, that is, polar coordinates with the sun as the origin. See Figure 4. However, they can alternatively be formulated and derived using Cartesian coordinates.

Equations of motion

See also: Mechanics of planar particle motion § Polar coordinates in an inertial frame of reference, and Centrifugal_force (rotating reference frame) § Planetary motionAssume that the planet is so much lighter than the sun that the acceleration of the sun can be neglected. In other words, the barycenter is approximated as the center of the sun. Introduce the polar coordinate system in the plane of the orbit, with radial coordinate from the sun's center, r and angle from some arbitrary starting direction θ.

Newton's law of gravitation says that "every object in the universe attracts every other object along a line of the centers of the objects, proportional to each object's mass, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the objects," and his second law of motion says that "the mass times the acceleration is equal to the force." So the mass of the planet times the acceleration vector of the planet equals the mass of the sun times the mass of the planet, divided by the square of the distance, times minus the radial unit vector , times a constant of proportionality. This is written:

where a dot on top of the variable signifies differentiation with respect to time, and the second dot indicates the second derivative.

where is the tangential (azimuthal) unit vector orthogonal to and pointing in the direction of rotation, and

So the position vector

is differentiated twice to give the velocity vector and the acceleration vector

Note that for constant distance, , the planet is subject to the centripetal acceleration, , and for constant angular speed, , the planet is subject to the Coriolis acceleration, .

Inserting the acceleration vector into Newton's laws, and dividing by m, gives the vector equation of motion

Equating components, we get the two ordinary differential equations of motion, one for the acceleration in the direction, the radial acceleration

and one for the acceleration in the direction, the tangential or azimuthal acceleration:

Deriving Kepler's second law

In order to derive Kepler's second law only the tangential acceleration equation is needed.

The magnitude of the specific angular momentum

is a constant of motion, even if both the distance , and the angular speed , and the tangential velocity , vary, because

where the expression in the last parentheses vanishes due to the tangential acceleration equation.

The area swept out from time t1 to time t2,

depends only on the duration t2−t1. This is Kepler's second law.

Deriving Kepler's first law

In order to derive Kepler's first law define

where the constant

has the dimension of length. Then

and

Differentiation with respect to time is transformed into differentiation with respect to angle:

Differentiate

twice:

Substitute into the radial equation of motion

and get

Divide by to get a simple non-homogeneous linear differential equation for the orbit of the planet:

An obvious solution to this equation is the circular orbit

Other solutions are obtained by adding solutions to the homogeneous linear differential equation with constant coefficients

These solutions are

where and are arbitrary constants of integration. So the result is

Choosing the axis of the coordinate system such that , and inserting , gives:

If this is Kepler's first law.

Deriving Kepler's third law

In the special case of circular orbits, which are ellipses with zero eccentricity, the relation between the radius a of the orbit and its period P can be derived relatively easily. The centripetal force of circular motion is proportional to a/P, and it is provided by the gravitational force, which is proportional to 1/a. Hence,

which is Kepler's third law for the special case.

In the general case of elliptical orbits, the derivation is more complicated.

The area of the planetary orbit ellipse is

The area speed of the radius vector sweeping the orbit area is

where

The period of the orbit is

satisfying

implying Kepler's third law

See also

- Kepler orbit

- Kepler problem

- Circular motion

- Gravity

- Two-body problem

- Free-fall time

- Laplace-Runge-Lenz vector

Notes

- Gerald James Holton, Stephen G. Brush (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure. Rutgers University Press. Chapter 4. ISBN 0813529085.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - "Kepler's Second Law" by Jeff Bryant with Oleksandr Pavlyk, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Gerald James Holton, Stephen G. Brush (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure. Rutgers University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0813529085.

- Gerald James Holton, Stephen G. Brush (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure. Rutgers University Press. p. 136. ISBN 0813529085.

- Hyman, Andrew. "A Simple Cartesian Treatment of Planetary Motion", European Journal of Physics, Vol. 14, pp. 145–147 (1993).

- Although this term is called the "Coriolis acceleration", or the "Coriolis force per unit mass", it should be noted that the term "Coriolis force" as used in meteorology, for example, refers to something different: namely the force, similar in mathematical form, but caused by rotation of a frame of reference. Of course, in the example here of planetary motion, the entire analysis takes place in a stationary, inertial frame, so there is no force present related to rotation of a frame of reference.

References

- Kepler's life is summarized on pages 627–623 and Book Five of his magnum opus, Harmonice Mundi (harmonies of the world), is reprinted on pages 635–732 of On the Shoulders of Giants: The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy (works by Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Newton, and Einstein). Stephen Hawking, ed. 2002 ISBN 0-7624-1348-4

- A derivation of Kepler's third law of planetary motion is a standard topic in engineering mechanics classes. See, for example, pages 161–164 of Meriam, J. L. (1966, 1971), Dynamics, 2nd ed., New York: John Wiley, ISBN 0-471-59601-9

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link).

- Murray and Dermott, Solar System Dynamics, Cambridge University Press 1999, ISBN-10 0-521-57597-4

External links

- B.Surendranath Reddy; animation of Kepler's laws: applet

- Crowell, Benjamin, Conservation Laws, http://www.lightandmatter.com/area1book2.html, an online book that gives a proof of the first law without the use of calculus. (see section 5.2, p.112)

- David McNamara and Gianfranco Vidali, Kepler's Second Law - Java Interactive Tutorial, http://www.phy.syr.edu/courses/java/mc_html/kepler.html, an interactive Java applet that aids in the understanding of Kepler's Second Law.

- University of Tennessee's Dept. Physics & Astronomy: Astronomy 161 page on Johannes Kepler: The Laws of Planetary Motion

- Equant compared to Kepler: interactive model

- Kepler's Third Law:interactive model

| Gravitational orbits | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types |

| ||||||||

| Parameters |

| ||||||||

| Maneuvers | |||||||||

| Orbital mechanics |

| ||||||||

. Although the two terms in this equation sum to zero mathematically, they still exist individually. They do not cancel each other out physically. As in the case of

. Although the two terms in this equation sum to zero mathematically, they still exist individually. They do not cancel each other out physically. As in the case of

is the orbital period of planet and

is the orbital period of planet and  is the semimajor axis of the orbit.

is the semimajor axis of the orbit.

is the

is the  is the mass of the sun, and

is the mass of the sun, and  is the mass of the planet. The discrepancy in Kepler's constant due to the mass of Jupiter is approximately a tenth of a percent. (See data tabulated at

is the mass of the planet. The discrepancy in Kepler's constant due to the mass of Jupiter is approximately a tenth of a percent. (See data tabulated at

= E = M.

= E = M.

distance between center and perihelion, the semimajor axis,

distance between center and perihelion, the semimajor axis, the eccentricity,

the eccentricity, the semiminor axis,

the semiminor axis, the distance between sun and planet.

the distance between sun and planet. the direction to the planet as seen from the sun, the

the direction to the planet as seen from the sun, the  the projection of the planet to the auxiliary circle

the projection of the planet to the auxiliary circle the point on the circle such that the sector areas |zcy| and |zsx| are equal,

the point on the circle such that the sector areas |zcy| and |zsx| are equal, the

the

,

,

, x as seen from the centre, the

, x as seen from the centre, the

, times a constant of proportionality. This is written:

, times a constant of proportionality. This is written:

is the tangential (azimuthal) unit vector orthogonal to

is the tangential (azimuthal) unit vector orthogonal to

, the planet is subject to the

, the planet is subject to the  , and for constant angular speed,

, and for constant angular speed,  , the planet is subject to the

, the planet is subject to the  .

.

, vary,

because

, vary,

because

to get a simple

to get a simple

and

and  are arbitrary constants of integration. So the result is

are arbitrary constants of integration. So the result is

, and inserting

, and inserting  , gives:

, gives:

this is Kepler's first law.

this is Kepler's first law.