This is an old revision of this page, as edited by DV8 2XL (talk | contribs) at 03:56, 16 November 2005 (reverting to last good version by Fastfusion). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 03:56, 16 November 2005 by DV8 2XL (talk | contribs) (reverting to last good version by Fastfusion)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

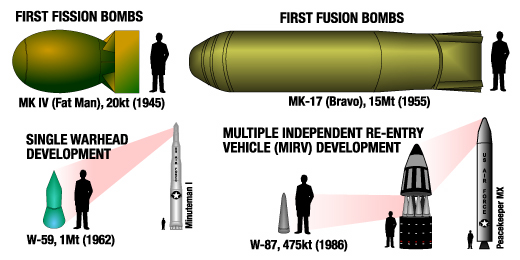

Nuclear weapon designs are often divided into two classes, based on the dominant source of the nuclear weapon's energy.

- Fission bombs derive their power from nuclear fission, where heavy nuclei (uranium or plutonium) are bombarded by neutrons and split into lighter elements, more neutrons and energy. These newly created neutrons then bombard other nuclei, which then split and bombard other nuclei, and so on, creating a nuclear chain reaction which releases large amounts of energy. These are historically called atomic bombs, atom bombs, or A-bombs, though this name is not precise due to the fact that chemical reactions release energy from atomic bonds and fusion is no less atomic than fission. Despite this possible confusion, the term atom bomb has still been generally accepted to refer specifically to nuclear weapons, and most commonly to pure fission devices.

- Fusion bombs are based on nuclear fusion where light nuclei such as deuterium and lithium combine together into heavier elements and release large amounts of energy. Weapons which have a fusion stage are also referred to as hydrogen bombs or H-bombs because of their primary fuel, or thermonuclear weapons because fusion reactions require extremely high temperatures for a chain reaction to occur.

The distinction between these two types of weapon is blurred by the fact that they are combined in nearly all complex modern weapons: a smaller fission bomb is first used to reach the necessary conditions of high temperature and pressure which are required for fusion. Fusion elements may also be present in the core of fission devices as well as they generate additional neutrons which increases the efficiency (known as "boosting") of the fission reaction. Additionally, most fusion weapons derive a substantial portion of their energy (often around half of the total yield) from a final stage of fissioning which is enabled by the fusion reactions. Since the distinguishing feature of both fission and fusion weapons is that they release energy from transformations of the atomic nucleus, the best general term for all types of these explosive devices is nuclear weapon.

Other specific types of nuclear weapon design which are commonly referred to by name include: neutron bomb (enhanced radiation weapon), cobalt bomb, and salted bomb.

Fission weapons

The simplest nuclear weapons are pure fission bombs. These were the first types of nuclear weapons built during the Manhattan Project and they are a building block for all advanced nuclear weapons designs.

Critical mass

A mass of fissile material is called critical when it is capable of a sustained chain reaction, which depends upon the size, shape and purity of the material as well as what surrounds the material. A numerical measure of whether a mass is critical or not is available as the neutron multiplication factor, k, where

- k = f − l

Where f is the average number of neutrons released per fission event and l is the average number of neutrons lost by either leaving the system or being captured in a non-fission event. When k = 1 the mass is critical, k < 1 is subcritical and k > 1 is supercritical. A fission bomb works by rapidly changing a subcritical mass of fissile material into a supercritical assembly, causing a chain reaction which rapidly releases large amounts of energy. In practice the mass is not made slightly critical, but goes from slightly subcritical (k = 0.9) to highly supercritical (k = 2 or 3), so that each neutron creates several new neutrons and the chain reaction advances more quickly. The main challenge in producing an efficient explosion using nuclear fission is to keep the bomb together long enough for a substantial fraction of the available nuclear energy to be released.

Until detonation is desired, the weapon must consist of a number of separate pieces each of which is below the critical size either because they are too small or unfavorably shaped. To produce detonation, the fissile material must be brought together rapidly. In the course of this assembly process the chain reaction is likely to start causing the material to heat up and expand, preventing the material from reaching its most compact (and most efficient) form. It may turn out that the explosion is so inefficient as to be practically useless. The majority of the technical difficulties of designing and manufacturing a fission weapon are based on the need to both reduce the time of assembly of a supercritical mass to a minimum and reduce the number of stray (pre-detonation) neutrons to a minimum.

The isotopes desirable for a nuclear weapon are those which have a high probability of fission reaction, yield a high number of excess neutrons, have a low probability of absorbing neutrons without a fission reaction, and do not release a large number of spontaneous neutrons. The primary isotopes which fit these criteria are U-235, Pu-239 and U-233.

Enriched materials

Uranium 235 and Plutonium 239 have so far been the fissionable materials used in atomic bombs.

Naturally occurring uranium consists mostly of U-238 (99.29%), with a small part U-235 (0.71%). The U-238 isotope has a high probability of absorbing a neutron without a fission, and also a higher rate of spontaneous fission. For weapons, uranium is enriched through isotope separation. Uranium which is more than 80% U-235 is called highly enriched uranium (HEU), and weapons grade uranium is at least 93.5% U-235. U-235 has a spontaneous fission rate of 0.16 fissions/s-kg. which is low enough to make super critical assembly relatively easy. The critical mass for an unreflected sphere of U-235 is about 50 kg, which is a sphere with a diameter of 17 cm. This size can be reduced to about 15 kg with the use of a neutron reflector surrounding the sphere.

Plutonium (atomic number 94, two more than uranium) occurs naturally only in small amounts within uranium ores. Military or scientific production of plutonium is achieved by exposing purified U-238 to a strong neutron source (e.g., in a breeder reactor). When U-238 absorbs a neutron the resulting U-239 isotope then beta decays twice into Pu-239. Pu-239 has a higher probability for fission than U-235, and a larger number of neutrons produced per fission event, resulting in a smaller critical mass. Pure Pu-239 also has a reasonably low rate of neutron emission due to spontaneous fission (10 fission/s-kg), making it feasible to assemble a supercritical mass before predetonation. In practice the plutonium produced will invariably contain a certain amount of Pu-240 due to the tendency of Pu-239 to absorb an additional neutron during production. Pu-240 has a high rate of spontaneous fission events (415,000 fission/s-kg), making it an undesirable contaminant. Weapons-grade plutonium must contain no more than 7% Pu-240; this is achieved by only exposing U-238 to neutron sources for short periods of time to minimize the Pu-240 produced. The critical mass for an unreflected sphere of plutonium is 16 kg, but through the use of a neutron reflecting tamper the pit of plutonium in a fission bomb is reduced to 10 kg, which is a sphere with a diameter of 10 cm.

Roughly the following values apply: there are 80 generations of the chain reaction, each requiring the time a neutron with a speed of 10,000 km/s needs to travel 10 cm; this takes 80 times 0.01 µs. Thus, the supercritical mass has to be kept together for 1 µs.

Combination methods

There are two techniques for assembling a supercritical mass. Broadly speaking, one brings two sub-critical masses together and the other compresses a sub-critical mass into a supercritical one.

Gun method

The simplest technique for assembling a supercritical mass is to shoot one piece of fissile material as a projectile against a second part as a target, usually called the gun method. This is roughly how the "Little Boy" weapon which was detonated over Hiroshima worked. In detail, it most likely utilized some arrangement of a uranium "bullet" powered by a cordite charge into a target of uranium rings, rather than using two hemispheres. The hollow cylindrical shape makes the 36 kg target subcritical. The rings allowed sub-critical assemblies to be tested using the same "bullet" but with just one ring.

The U-235 "bullet" had, in the case of Little Boy, a mass of ca. 24 kg, and it was 16 cm long, with a diameter of 10 cm. It travelled with a speed of 300 m/s when the cordite exploded. The barrel, weighing 450 kg, was that of an anti-aircraft gun, with a 16 cm outer diameter, and the 7.5 cm inside diameter bored out to 10 cm. Its length was 180 cm.

Thus, after the bullet arrives at the target, it takes 0.5 ms to slide inside. Because of this relatively long amount of time it takes to combine the materials, this method of combination can only be used for U-235: predetonation is likely for Pu-239 which has a higher spontaneous neutron release due to Pu-240 contamination.

For a quick start of the chain reaction at the right moment a neutron trigger / initiator is used, see below.

Although in Little Boy 60 kg of 80% grade U-235 was used (hence 48 kg), the minimum is ca. 20 to 25 kg, versus 15 kg for the implosion method.

For technologically advanced states the method is essentially obsolete, see below. With regard to the risk of proliferation and use by terrorists, the relatively simple design is a concern, as it does not require as much fine engineering or manufacturing as other methods. With enough highly-enriched uranium, nations or groups with relatively low levels of technological sophistication could create an inefficient — though still quite powerful — gun-type nuclear weapon.

The scientists who designed the "Little Boy" weapon were confident enough of its likely success that they did not test a design first before using it in war. In any event, it could not be tested before being deployed as there was only sufficient U-235 available for one device.

Implosion method

The more difficult, but in many ways superior, method of combination is referred to as the implosion method and uses conventional explosives surrounding the material to rapidly compress the mass to a supercritical state. This compression reduces the volume by a factor 2 to 5.

For Pu-239 assemblies a contamination of only 1% of Pu-240 produces so many spontaneous neutrons that a gun-type device would very likely begin fissioning before fully assembled, leading to very low efficiency. For this reason the more technically difficult implosion method must be used for plutonium bombs such as the test bomb used in the "Trinity" shot and the subsequent "Fat Man" weapon detonated over Nagasaki.

Weapons assembled with this method also tend to be generally more efficient than the weapons employing the gun method of combination even ignoring the problem of spontaneous neutrons. The reason that the implosion method is more efficient is because it not only combines the masses, but also increases the density of the mass, and thereby increases the neutron multiplication factor k of the fissionable assembly. Most modern weapons use a hollow plutonium core or pit with an implosion mechanism for detonation.

A two fold increase in the density of the atomic pit will tend to result in a 10-20 kiloton atomic explosion. A 3-fold compression may produce a 40-45 kiloton atomic yield, a four fold compression may produce a 60-80 kiloton atomic yield, and a five-fold compression of the pit which is very hard to get, may produce an 80-100 kiloton atomic yield. Getting a 5-fold compression of the pit requires a very strong, massive, and very efficient, lens implosion system.

This precision compression of the pit creates a need for very precise design and machining of the pit and explosive lenses. The milling machines used are so precise that they could cut the polished surfaces of eyeglass lenses. There are strong suggestions that modern implosion devices use non-spherical configurations as well, such as ovoid shapes ("watermelons").

Pit

Casting and then machining plutonium is difficult not only because of its toxicity but also because plutonium has many different metallic phases and changing phases as it cools distorts the metal. This is normally overcome by alloying it with 3–3.5 molar% (0.9–1.0% by weight) gallium which makes it take up its delta phase over a wide temperature range. When cooling from molten it then only suffers a single phase change, from its epsilon phase to the delta one instead of four changes. Other trivalent metals would also work, but gallium has a small neutron absorption cross section and helps protect the plutonium against corrosion. A drawback is that gallium compounds themselves are corrosive and so if the plutonium is recovered from dismantled weapons for conversion to plutonium oxide for power reactors, there is the difficulty of removing the gallium. Modern pits are often composites of plutonium and uranium-235.

Because plutonium is chemically reactive and toxic if inhaled or enters the body by any other means, it is usual to plate the completed pit with a thin layer of inert metal. In the first weapons, nickel was used but gold is now preferred.

Explosive lenses

It is not good enough to pack explosive in a spherical shell around the tamper and detonate it simultaneously at several places because the tamper and plutonium pit will simply be squeezed out of the gaps in the detonation front. Instead the shock wave must be carefully shaped into a perfect sphere centred on the pit and travelling inwards. This is done by carefully shaping it using a spherical shell made of closely fitting and accurately shaped bodies of explosives of different propagation speeds to form explosive lenses.

The lenses must be accurately shaped, chemically pure and homogenous for precise control of the speed of the detonation front. The casting and testing of these lenses was a massive technical challenge in the development of the implosion method in the 1940s, as was measuring the speed of the shock wave and the performance of prototype shells. It also required electric exploding-bridgewire detonators to be developed which would explode at exactly the same moment so that the explosion starts at the centre of each of the lenses simultaneously (within less than 100 nanoseconds). Once the shock wave has been shaped, there may also be an inner homogenous spherical shell of explosive to give it greater force, known as a supercharge.

The bomb dropped onto Nagasaki used 32 lenses, while more efficient bombs would later use 92 lenses.

The exploding-bridgewire detonators were later replaced by slapper detonators, a similar but improved design that is now used in modern weapons, both nuclear and conventional.

Pusher

The explosion shock wave might be of such short duration that only a fraction of the pit is compressed at any instance as it passes through it. A pusher shell made out of low density metal such as aluminium, beryllium, or an alloy of the two metals (aluminium being easier and safer to shape but beryllium reflecting neutrons back into the core) may be needed and is located between the explosive lens and the tamper. It works by reflecting some of the shock wave backwards which has the effect of lengthening it. The tamper or reflector might be designed to work as the pusher too, although a low density material is best for the pusher but a high density one for the tamper. To maximize efficiency of energy transfer, the density difference between layers should be minimized.

Most U.S. weapons since the 1950s have employed a concept called pit "levitation," whereby an air gap is introduced between the pusher and the pit. The effect of this is to allow the pusher to gain momentum before it hits the core, which allows for more efficient and complete compression. A common analogy is that of a hammer and a nail: leaving space between the hammer and nail before striking greatly increases the compressive power of the hammer (as compared to putting the hammer right on top of the nail before beginning to push).

Many modern nuclear weapons use a hollow sphere of Pu-239, or U-235 that is placed inside of a hollow sphere of beryllium, tungsten carbide, or U-238 that serves as the tamper. This may also be placed inside of a hollow pusher sphere made of aluminium, steel, or other metallic material. Additionaly a gram or so of tritium and/or deuterium gas may be injected into the hollow core prior to implosion to achieve a "boosting" effect from small amounts of nuclear fusion (see below).

Tamper reflector

A tamper is an optional layer of dense material (typically natural or depleted uranium or tungsten) surrounding the fissile material. It reduces the critical mass and increases the efficiency by its inertia which delays the expansion of the reacting material.

The tamper prolongs the very short time the material holds together under the extreme pressures of the explosion, and thereby increases the efficiency, i.e. the fraction of the fissile material that actually fissions. The high density has more effect on that than high tensile strength. A coincidence that is fortunate from the point of view of the weapon designer is that materials of high density are also excellent reflectors of neutrons.

While the effect of a tamper is to increase the efficiency both by reflecting neutrons and by delaying the expansion of the core, the effect on the efficiency is not as great as the effect on the critical mass. The reason for this is that the process of reflection is relatively time consuming and may not occur extensively before the chain reaction is terminated.

Neutron reflector

A neutron reflector layer is an optional layer commonly found as the closest layer surrounding the fissile material. This may be the same material used in the tamper, or a separate material. While many tamper materials are adequate reflectors, the best reflector (beryllium metal) makes an extremely poor tamper.

The most efficient reflector is believed to be beryllium metal, then beryllium oxide and tungsten carbide roughly equally efficient, then uranium, then tungsten, then copper, then water, then graphite and iron which are roughly equally efficient.

There is a design tradeoff in choosing to employ a tamper, reflector, or combined material. The weight of the combined pit assembly (any pusher, tamper, reflector, and the fissile material all together) has to be accelerated inwards by the implosion assembly explosives. The larger the pit assembly, the more explosives are needed to implode it to a given velocity and pressure. Early implosion nuclear weapons used heavy pushers and tampers, which were moderately effective reflectors (natural uranium tampers, for example). Levitated or hollow pits increase the energy efficiency of implosion. Using highly efficient, lightweight reflectors made of beryllium further increases the mass efficiency of the implosion system. Such pits are only slightly tamped, and will dissassemble very rapidly once the fission reaction reaches high energy levels.

Before fusion boosting, it was arguable whether the most efficient overall system employed dedicated high mass tampers or not. Now that modern weapons typically use fusion boosting, which increases the reaction rate tremendously, lack of tamper material is no longer a drawback. This has helped allow for the miniaturization of nuclear weapon systems.

Neutron trigger / initiator

One of the key elements in the proper operation of a nuclear weapon is initiation of the fission chain reaction at the proper time. To obtain a significant nuclear yield of the nuclear explosive, sufficient neutrons must be present within the supercritical core at just the right time. If the chain reaction starts too soon, the result will be only a 'fizzle yield', much below the design specification; if it occurs too late, there may be no yield whatsoever. Several ways to produce neutrons at the appropriate moment have been developed.

Early neutron triggers consisted of a highly radioactive isotope of Polonium (Po-210), which is a strong alpha emitter combined with beryllium which will absorb alphas and emit neutrons. This isotope of polonium has a half life of almost 140 days. Therefore, a neutron initiator using this material needs to have the polonium replaced frequently. The polonium is produced in a nuclear reactor.

To supply the initiation pulse of neutrons at the right time, the polonium and the beryllium need to be kept apart until the appropriate moment and then thoroughly and rapidly mixed by the implosion of the weapon. This method of neutron initiation is sufficient for weapons utilizing the slower gun combination method, but the timing is not precise enough for an implosion weapon design. The "Fat Man" weapon of World War II used a finely tooled initiator known as an "urchin", made of alternating concentric layers of beryllium and polonium separated with thin gold foils.

Another method of providing source neutrons is through a pulsed neutron emitter, which is a small ion accelerator with a metal hydride target. When the ion source is turned on to create a plasma of deuterium or tritium, a large voltage is applied across the tube which accelerates the ions into tritium rich metal (usually scandium). The ions are accelerated so that there is a high probability of nuclear fusion occurring. The deuterium-tritium fusion reactions emit a short pulse of 14 MeV neutrons which will be sufficient to initiate the fission chain reaction. The timing of the pulse can be precisely controlled, making it better for an implosion weapon design.

An initiator is not strictly necessary for an effective gun design , as long as the design uses "target capture" (in essence, ensuring that the two subcritical masses, once fired together, cannot come apart until they explode). Initiators were only added to Little Boy late in its design. The use of an initiator can guarantee precise control (to the millisecond) over the timing of the explosion.

Comparison of the two methods

The gun type method is essentially obsolete and was abandoned by the United States as soon as the implosion technique was perfected. Other nuclear powers, such as the United Kingdom, never even built an example of this type of weapon. As well as only being possible to produce this weapon using highly enriched U-235, the technique has other severe limitations. The implosion technique is much better suited to the various methods employed to reduce the weight of the weapon and increase the proportion of material which fissions.

There are also safety problems with gun type weapons. For example, it is inherently dangerous to have a weapon containing a quantity and shape of fissile material which can form a critical mass through a relatively simple accident. Furthermore if the weapon is dropped from an aircraft into the sea, then the moderating effect of the light sea water can also cause a criticality accident without the weapon even being physically damaged. Neither can happen with an implosion type weapon since there is normally insufficent fissile material to form a critical mass without the correct detonation of the lenses.

Implosion type weapons normally have the pit physically removed from the centre of the weapon and only inserted during the arming procedure so that a nuclear explosion cannot occur even if a fault in the firing circuits causes them to detonate the explosive lenses simultaneously as would happen during correct operation. It has also been hypothesized, based on open sources, that the Permissive Action Links for some types of nuclear weapons may involve the use of encoded secret timing offsets for the explosives in a given weapon's combination of explosives and lenses, needed to create a unified focus for the shockfront.

Alternatively, the pit can be "safed" by having its normally-hollow core filled with an inert material such as a fine metal chain. While the chain is in the center of the pit, the pit can't be compressed into an appropriate shape to fission; when the weapon is to be armed, the chain is removed. Similarly, a serious fire will detonate the explosives, destroying the pit and spreading plutonium to contaminate the surroundings (as has happened in several weapons accidents) but cannot possibly cause a nuclear explosion.

The South African nuclear program was probably unique in adopting the gun technique to the exclusion of implosion type devices, and built around five of these weapons before they abandoned their program.

Practical limitations of the fission bomb

A pure fission bomb is practically limited to a yield of a few hundred kilotons by the large amounts of fissile material needed to make a large weapon. It is technically difficult to keep a large amount of fissile material in a subcritical assembly while waiting for detonation, and it is also difficult to physically transform the subcritical assembly into a supercritical one quickly enough that the device explodes rather than prematurely detonating such that a majority of the fuel is unused (inefficient predetonation). The most efficient pure fission bomb possible would still only consume ~25% of its fissile material before being blown apart, and can often be much less efficient (Fat Man only had an efficiency of 14%, Little Boy only about 1.4% efficient). Large yield, pure fission weapons are also unattractive due to the weight, size, and cost of using large amounts of highly enriched material.

Another limitation of some fission bomb designs is the need to keep the electronic circuitry within a certain range of temperatures to prevent malfunction. Some weapons were designed with internal heaters to maintain a stable temperature (a method still used by NASA in its space probes); other, more unusual, methods were contemplated by the United Kingdom (see chicken powered nuclear bomb).

Thermonuclear weapons (also Hydrogen bomb or fusion bomb)

The amount of energy released by a weapon can be greatly increased by the addition of nuclear fusion reactions. Fusion releases even more energy per reaction than fission, and can also be used as a source for additional neutrons. The light weight of the elements used as fusion fuel, combined with the larger energy release, means that fusion is a very efficient fuel by weight, making it possible to build extremely high yield weapons which are still portable enough to easily deliver. Fusion is the combination of two light atoms, usually isotopes of hydrogen, to form a more stable heavy atom and release excess energy. The fusion reaction requires the atoms involved to have a high thermal energy, which is why the reaction is called thermonuclear. The extreme temperatures and densities necessary for a fusion reaction are easily generated by a fission explosion. A pure fusion weapon is a hypothetical design that does not need a fission primary, but no weapons of this sort have ever been developed.

Fusion boosting

The simplest way to utilize fusion is to put a mixture of deuterium and tritium inside the hollow core of an implosion style plutonium pit (which usually requires an external neutron generator mounted outside of it rather than the initiator in the core as in the earliest weapons). When the imploding fission chain reaction brings the fusion fuel to a sufficient pressure, a deuterium-tritium fusion reaction occurs and releases a large number of energetic neutrons into the surrounding fissile material. This increases the rate of burn of the fissile material and so more is consumed before the pit disintegrates. The efficiency (and therefore yield) of a pure fission bomb can be doubled (from about 20% to about 40% in an efficient design) through the use of a fusion boosted core, with very little increase in the size and weight of the device. The amount of energy released through fusion is only around 1% of the energy from fission, so the fusion chiefly increases the fission efficiency by providing a burst of additional neutrons.

Fusion boosting provides two strategic benefits. The first is that it obviously allows weapons to be made much smaller, lighter, and use less fissile material for a given yield, making them cheaper to build and deliver. The second benefit is that it can be used to render weapons immune to radiation interference (RI). It was discovered in the mid-1950s that plutonium pits would be particularly susceptible to partial pre-detonation if exposed to the intense radiation of a nearby nuclear explosion (electronics might also be damaged, but this was a separate issue). RI was a particular problem before effective early warning radar systems because a first strike attack might make retaliatory weapons useless. Boosting can reduce the amount of plutonium needed in a weapon to below the quantity which would be vulnerable to this effect.

While this technique, sometimes known as "gas boosting," uses fusion — the reaction associated with the so-called “hydrogen bomb” — it is still seen as simply boosting what is still properly a “fission” bomb. In fact, fusion boosting is very common and used in most modern weapons, including the fission primaries in most thermonuclear weapons.

Staged thermonuclear weapons

The basic principles behind modern thermonuclear weapons design were developed independently by scientists in different countries. Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam at Los Alamos worked out the idea of staged detonation coupled with radiation implosion in what is known in the United States as the Teller-Ulam design in 1951. Soviet physicist Andrei Sakharov independently arrived at the same answer (which he called his "Third Idea") in 1955.

The full details of staged thermonuclear weapons have never been fully declassified and among different sources outside the wall of classification there is no strict consensus over how exactly a hydrogen bomb works. The basic principles are revealed through two separate declassified lines by the US Department of Energy: "The fact that in thermonuclear (TN) weapons, a fission 'primary' is used to trigger a TN reaction in thermonuclear fuel referred to as a 'secondary'" and "The fact that, in thermonuclear weapons, radiation from a fission explosive can be contained and used to transfer energy to compress and ignite a physically separate component containing thermonuclear fuel."

A general interpretation of this, following on the 1979 court case of United States v. The Progressive (which sought to censor an article about the workings of the hydrogen bomb; the government eventually dropped the case and much new information about the weapon was declassified), is as follows:

A fission weapon (the "primary") is placed at one end of the warhead casing. When detonated, it first releases X-rays at the speed of light. These are reflected from the casing walls, which are made of heavy metals and serve as X-ray mirrors. The X-rays travel into a space surrounding the secondary, which is a column or sphere of lithium-deuteride fusion fuel encased by a natural uranium "tamper"/"pusher". Here, the X-rays cause a pentane-impregnated polystyrene foam filling the case to convert into a plasma, and the X-rays cause ablation of the surface of the jacket surrounding the secondary, imploding it with enormous force. Inside the secondary is a "sparkplug" of either enriched uranium or plutonium, which is caused to fission by the compression, and begins its own nuclear explosion. Compression of the fusion fuel and the high temperature caused by the fission explosion cause the deuterium to fuse into helium and emit copious neutrons. The neutrons transmute the lithium to tritium, which then also fuses and emits large amounts of gamma rays and more neutrons. The excess neutrons then cause the natural uranium in the "tamper", "pusher", case and x-ray mirrors to undergo fission as well, adding more power to the yield.

The process by which the “secondary” (fusion) stage is compressed by the x-rays from the “primary” (fission) stage is known as “radiation implosion.” It was widely misunderstood for many years and is incorrectly depicted in many authorities, including Rhodes (1986) and in the Progressive article. The actual mechanism that compresses the secondary stage is neither the “radiation pressure” of the x-rays, nor the physical pressure of the plasmatized foam. It is also not attributable to a neutron flux or hydrodynamic shock moving down from the primary. Instead it is only the x-ray radiation 'burning' the outside surface of the tamper/pusher away. X-rays surround and heat the whole outside of the tamper/pusher until the outside layer of it ablates/explodes away from the secondary in all directions, creating an inward “ablation pressure.” In other words, heated by x-rays, the outside layers of the tamper/pusher explode outward, like a rocket, driving the remaining layers inward in an implosion.

Advanced thermonuclear weapons designs

The largest modern fission-fusion-fission weapons include a fissionable outer shell of U-238, the more inert waste isotope of uranium, or X-ray mirrors constructed of polished U-238. This otherwise inert U-238 would be detonated by the intense fast neutrons from the fusion stage, increasing the yield of the bomb many times. For maximum yield, however, moderately enriched uranium is preferable as a jacket material. For the purposes of miniaturization of weapons (fitting them into the small re-entry vehicles on modern MIRVed missiles), it has also been suggested that many modern thermonuclear weapons use spherical secondary stages, rather than the column shapes of the older hydrogen bombs.

Multi-staged thermonuclear devices have been developed. In such a design, a fission “primary” is used to compress a fusion “secondary,” in the usual fashion, but that explosion is, in turn, used to compress another, much larger fusion stage, the “tertiary.” A three-stage bomb, the Mk. 41, was deployed by the United States and the USSR’s Tsar Bomba, was also a three stage weapon. In theory, there is no limit to how many stages could be added, though there is no foreseeable need for five or six stage weapons with yields which could approach a gigaton.

The cobalt bomb uses cobalt in the shell, and the fusion neutrons convert the cobalt into cobalt-60, a powerful long-term (5 years) emitter of gamma rays, which produces major radioactive contamination. In general this type of weapon is a salted bomb and variable fallout effects can be obtained by using different salting isotopes. Gold has been proposed for short-term fallout (days), tantalum and zinc for fallout of intermediate duration (months). To be useful for salting, the parent isotopes must be abundant in the natural element, and the neutron-bred radioactive product must be a strong emitter of penetrating gamma rays.

The primary purpose of this weapon is to create extremely radioactive fallout to deny a region to an advancing army, a sort of wind-deployed mine-field. No cobalt weapons have have ever been atmospherically tested, and as far as is publicly known none have ever been built. A number of very "dirty" thermonuclear weapons, however, have been developed and detonated, as the final fission stage (usually a jacket of natural or enriched uranium) is itself sometimes analogous to "salting" (for example, the Castle Bravo shot). The British did test a bomb that incorporated cobalt as an experimental radiochemical tracer (Antler/Round 1, 14 September 1957). This 1 kt device was exploded at the Tadje site, Maralinga range, Australia. The experiment was regarded as a failure and not repeated.

The thought of using cobalt, which has the longest half-life of the feasible salting materials, caused Leó Szilárd to refer to the weapon as a potential doomsday device. With a five year half-life, people would have to remain shielded underground for a very long time until it was safe to emerge, effectively wiping out humanity. However, no nation has ever been known to pursue such a strategy. The movie Dr. Strangelove famously incorporated such a doomsday weapon as a major plot device.

A final variant of the thermonuclear weapons is the enhanced radiation weapon, or neutron bomb which are small thermonuclear weapons in which the burst of neutrons generated by the fusion reaction is intentionally not absorbed inside the weapon, but allowed to escape. The X-ray mirrors and shell of the weapon are made of chromium or nickel so that the neutrons are permitted to escape.

This intense burst of high-energy neutrons is the principal destructive mechanism. Neutrons are more penetrating than other types of radiation so many shielding materials that work well against gamma rays do not work nearly as well. The term "enhanced radiation" refers only to the burst of ionizing radiation released at the moment of detonation, not to any enhancement of residual radiation in fallout (as in the salted bombs discussed above).

Miniaturization

The first nuclear weapons developed were large and idiosyncratic devices which weighed many tons and could only be dropped out of especially large aircraft as gravity bombs. In the years immediately after World War II, though, developments in rocketry spurred efforts to reduce the size of nuclear weapons to the point that they could fit on a missile. Over time, miniaturization of weapons has proven a major investment of nations with nuclear weapons, and one of the primary justifications used for programs of nuclear testing, which provide the raw data necessary for pushing the limits of nuclear weapons design. Weapons systems which require relatively small thermonuclear weapons, such as MIRVed missiles, are thought to be obtainable only with large amount of test result data. The physically smallest nuclear warheads deployed by the United States was the W54, used in the Davy Crockett recoilless rifle; the warheads in this weapon weighed about 23 kilograms and had yields ranging between 0.01 and 0.25 kilotons. This is small by comparison to thermonuclear weapons, but remains a very large explosion with lethal acute radiation effects and potential for substantial fallout. It is generally believed that the W54 is close to the smallest possible nuclear weapon.

Stockpile stewardship

In the years after the Cold War, most nuclear powers eventually stopped conducting programs of nuclear testing, primarily for political reasons. In many countries this has led to questions about how much was known about the safety and reliability of aging nuclear weapons systems. In the U.S., a program of stockpile stewardship has attempted to test the reliability of old warheads without full nuclear testing, often by using computer simulation.

References

- Glasstone, Samuel and Dolan, Philip J., The Effects of Nuclear Weapons (third edition), U.S. Government Printing Office, 1977. PDF Version

- Nuclear Weapon Archive from Carey Sublette is a reliable source of information and has links to other sources.

- The Federation of American Scientists provide solid information on weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear weapons and their effects

- Cohen, Sam, The Truth About the Neutron Bomb: The Inventor of the Bomb Speaks Out, William Morrow & Co., 1983

- Militarily Critical Technologies List (MCTL) from the US Government's Defense Technical Information Center

- Grace, S. Charles, Nuclear Weapons: Principles, Effects and Survivability (Land Warfare: Brassey's New Battlefield Weapons Systems and Technology, vol 10)

- Smyth, Henry DeWolf, Atomic Energy for Military Purposes, Princeton University Press, 1945. (see: Smyth Report)

- The Effects of Nuclear War, Office of Technology Assessment (May 1979).

- Rhodes, Richard. Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. Simon and Schuster, New York, (1995 ISBN 0684824140)

- Rhodes, Richard. The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Simon and Schuster, New York, (1986 ISBN 0684813785)

- More information on the design of two-stage fusion bombs