This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 205.188.117.69 (talk) at 22:12, 10 January 2006. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:12, 10 January 2006 by 205.188.117.69 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Template:Mtnbox start norange Template:Mtnbox coor dm Template:Mtnbox volcano Template:Mtnbox climb Template:Mtnbox finish

- This article is about the volcano in Italy. For other uses, see Vesuvius (disambiguation).

Mount Vesuvius (Italian: Monte Vesuvio) is a volcano east of Naples, Italy, located at 40°49′N 14°26′E / 40.817°N 14.433°E / 40.817; 14.433. It is the only active volcano on the European mainland, although it is not currently erupting. There are two other active volcanoes in Italy, although not located on the Italian mainland. Vesuvius is situated on the coast of the Bay of Naples, about nine kilometres (six miles) to the east of the city and a short distance inland from the shore. It forms a conspicuous feature in the beautiful landscape presented by that bay, when viewed from the sea, with the city in the foreground. The mountain is notorious for its destruction of the Roman city of Pompeii in AD 79. It also destroyed the town of Herculaneum in the same year; it has erupted many times since and is today regarded as one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world.

Origin of the name

Mount Vesuvius was regarded by the Greeks and Romans as being sacred to the hero and demigod Hercules/Heracles, and the town of Herculaneum, built at its base, was named after him. The mountain is also named after Hercules in a less direct manner: he was the son of the god Zeus and Alcmene of Thebes. Zeus was also known as Ves (Template:Polytonic) in his aspect as the god of rains and dews. Hercules was thus alternatively known as Vesouvios (Template:Polytonic), "Son of Ves." This name was corrupted into "Vesuvius."

According to other sources, Vesuvius came from the Oscan word fesf which means "smoke."

There is a theory that the name "Vesuvius" is derived from the Indo-European root ves- = "hearth".

Physical aspects

Vesuvius is a distinctive "humpbacked" mountain, consisting of a large cone partially encircled by a large secondary summit, Monte Somma (actually the remains of a huge ancient cone destroyed in a catastrophic eruption, probably the famous one of AD 79). The height of the main cone is constantly modified by eruptions but presently stands at 1,281m (4,202ft). Monte Somma is 1,149m (3,770ft) high, separated from the main cone by the valley of Atrio di Cavallo, which is some 3 miles (5 km) long. The slopes of the mountain are scarred by lava flows but are heavily vegetated, with scrub at higher altitudes and vineyards lower down. It is still regarded as an active volcano although its activity currently is limited to little more than steam from vents at the bottom of the crater. The area around the mountain is densely populated, with more than two million people living in the region and on the volcano's slopes.

Vesuvius is a composite volcano at the convergent boundary where the African Plate is being subducted beneath the Eurasian Plate. Its lava is composed of viscous andesite. Layers of lava, scoriae, ashes, and pumice make up the mountain.

Eruptions

Vesuvius has erupted repeatedly in recorded history, most famously in 79 and subsequently in 472, 512, in 1631, six times in the 18th century, eight times in the 19th century (notably in 1872), and in 1906, 1929, and 1944. There has been no eruption since then. The eruptions vary greatly in severity but are characterised by explosive outbursts of the kind dubbed Plinian after the Roman writer who observed the AD 79 eruption. On occasion, the eruptions have been so large that the whole of southern Europe has been blanketed by ashes; in 472 and 1631, Vesuvian ashes fell on Constantinople (now known as Istanbul), over 1,000 miles away. The volcano has been quiescent since 1944.

Before AD 79

Well before the famous eruption of 79 which destroyed the Roman towns of Stabiae, Pompeii, and Herculaneum, Vesuvius had erupted violently and destroyed Stone Age and Bronze Age settlements as far back as 1800 BC. The remains of a settlement at Nola was discovered recently by Italian archaeologists, with huts, pots, pans, livestock and the remains of people buried under pumice and ash in much the same way that Pompeii was later destroyed.

The mountain subsequently went through several centuries of quiescence and was described by Roman writers as having been covered with gardens and vineyards, except at the top which was craggy. Within a large circle of nearly perpendicular cliffs was a flat space large enough for the encampment of the army of the rebel gladiator Spartacus in 73 BC. This area was doubtless an ancient crater, left from the last major eruption of Vesuvius. At the time, the mountain appears to have had only one summit (of which the present Monte Somma is a fragment), judging by a painting found in a Pompeiian house.

By the time the Greeks and Romans settled the area, the nature of the mountain had entirely been forgotten. The area was, then as now, densely populated with villages, towns and small cities like Pompeii, and its slopes were covered in vineyards and farms.

Eruption of 79

The devastating eruption of 79 was preceded by powerful earthquakes in 62, which caused widespread destruction around the Bay of Naples. Earth tremors were commonplace in the region. The Romans, however, were entirely ignorant of the link between earthquakes and vulcanism, and grew used to them; the writer Pliny the Younger wrote that they "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania."

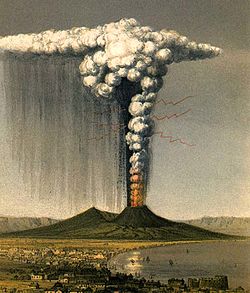

This complacency proved fatal for many on August 24, 79, when the mountain erupted spectacularly. It was recorded for posterity by Pliny the Younger, who observed the eruption and recorded it in a famous letter to the historian Tacitus. He saw an extraordinarily dense and rapidly-rising cloud appearing above the mountain:

- I cannot give you a more exact description of its figure, than by resembling it to that of a pine tree; for it shot up to a great height in the form of a tall trunk, which spread out at the top into a sort of branches. It appeared sometimes bright, and sometimes dark and spotted, as it was either more or less impregnated with earth and cinders.

What he had seen was a column of ash, now estimated to have been more than 20 miles (32 km) tall.

His uncle Pliny the Elder was that day in command of the Roman fleet at Misenum, on the far side of the bay, and decided to see for himself what was going on. Taking a ship across the bay, the elder Pliny encountered thick showers of hot cinders, lumps of pumice and pieces of rock, blocking his approach to the port of Retina. He went instead to Stabiae where he landed and took shelter with Pomponianus, a friend, in the town's bath house.

Pliny and his party saw flames coming from several parts of the mountain (probably a sign of superheated pyroclastic flows, which would later destroy Pompeii and Herculaneum). After resting for a short time in the bath