This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 72.89.194.37 (talk) at 00:45, 6 October 2010 (→Life). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:45, 6 October 2010 by 72.89.194.37 (talk) (→Life)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Copernicus" redirects here. For other uses, see Copernicus (disambiguation).| Nicolaus Copernicus | |

|---|---|

Portrait, 1580, Toruń Old Town City Hall Portrait, 1580, Toruń Old Town City Hall | |

| Born | (1473-02-19)19 February 1473, Toruń (Thorn), Royal Prussia, Kingdom of Poland |

| Died | 24 May 1543(1543-05-24) (aged 70), Frombork (Frauenburg), Prince-Bishopric of Warmia, Kingdom of Poland |

| Alma mater | Kraków University, Bologna University, University of Padua, University of Ferrara |

| Known for | Heliocentrism |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics, astronomy, canon law, medicine, economics |

| Signature | |

Nicolaus Copernicus (Template:Lang-pl; Template:Lang-de; in his youth, Niclas Koppernigk; Template:Lang-it; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance astronomer and the first person to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology, which displaced the Earth from the center of the universe.

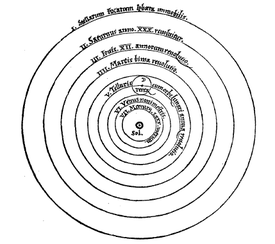

Copernicus' epochal book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), published just before his death in 1543, is often regarded as the starting point of modern astronomy and the defining epiphany that began the scientific revolution. His heliocentric model, with the Sun at the center of the universe, demonstrated that the observed motions of celestial objects can be explained without putting Earth at rest in the center of the universe. His work stimulated further scientific investigations, becoming a landmark in the history of science that is often referred to as the Copernican Revolution.

Among the great polymaths of the Renaissance, Copernicus was a mathematician, astronomer, physician, quadrilingual polyglot, classical scholar, translator, artist, Catholic cleric, jurist, governor, military leader, diplomat and economist. Among his many responsibilities, astronomy figured as little more than an avocation – yet it was in that field that he made his mark upon the world.

this all fake i hate is site

Copernican system

Main article: Copernican heliocentrismPredecessors

Philolaus (c. 480–385 BCE), a Greek philosopher of the Pythagorean school, described an astronomical system in which the Earth, Moon, Sun, planets, and stars all revolved about a central fire. Heraclides Ponticus (387–312 BCE) proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis. According to Archimedes, Aristarchus of Samos (310–230 BCE) wrote of heliocentric hypotheses in a book that does not survive. Plutarch wrote that Aristarchus was accused of impiety for "putting the Earth in motion".

In a manuscript of De revolutionibus, Copernicus wrote, "It is likely that ... Philolaus perceived the mobility of the earth, which also some say was the opinion of Aristarchus of Samos", but later struck out the passage and omitted it from the published book.

Ptolemy

Main article: AlmagestThe prevailing theory in Europe during Copernicus' lifetime was the one that Ptolemy published in his Almagest circa 150 CE. Ptolemy's system drew on previous Greek theories in which the Earth was the stationary center of the universe. Stars were embedded in a large outer sphere which rotated rapidly, approximately daily, while each of the planets, the Sun, and the Moon were embedded in their own, smaller spheres. Ptolemy's system employed devices, including epicycles, deferents and equants, to account for observations that the paths of these bodies differed from simple, circular orbits centered on the Earth. Ptolemy's model was refined by the 10th-century astronomer Muhammad al Battani, working at Ar-Raqqah in modern-day Syria. Although al Battani accepted the validity of the Ptolemaic model, Copernicus made much use of his astronomical observations in demonstrating the heliocentric theory, and gave acknowledgement to his predecessor in De revolutionibus.

Copernicus

Copernicus' major theory was published in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), in the year of his death, 1543, though he had formulated the theory several decades earlier.

Copernicus' "Commentariolus" summarized his heliocentric theory. It listed the "assumptions" upon which the theory was based as follows:

1. There is no one center of all the celestial circles or spheres.

2. The center of the earth is not the center of the universe, but only of gravity and of the lunar sphere.

3. All the spheres revolve about the sun as their mid-point, and therefore the sun is the center of the universe.

4. The ratio of the earth's distance from the sun to the height of the firmament (outermost celestial sphere containing the stars) is so much smaller than the ratio of the earth's radius to its distance from the sun that the distance from the earth to the sun is imperceptible in comparison with the height of the firmament.

5. Whatever motion appears in the firmament arises not from any motion of the firmament, but from the earth's motion. The earth together with its circumjacent elements performs a complete rotation on its fixed poles in a daily motion, while the firmament and highest heaven abide unchanged.

6. What appear to us as motions of the sun arise not from its motion but from the motion of the earth and our sphere, with which we revolve about the sun like any other planet. The earth has, then, more than one motion.

7. The apparent retrograde and direct motion of the planets arises not from their motion but from the earth's. The motion of the earth alone, therefore, suffices to explain so many apparent inequalities in the heavens.

De revolutionibus itself was divided into six parts, called "books":

- General vision of the heliocentric theory, and a summarized exposition of his idea of the World

- Mainly theoretical, presents the principles of spherical astronomy and a list of stars (as a basis for the arguments developed in the subsequent books)

- Mainly dedicated to the apparent motions of the Sun and to related phenomena

- Description of the Moon and its orbital motions

- Concrete exposition of the new system

- Concrete exposition of the new system

Successors

Georg Joachim Rheticus could have been Copernicus' successor, but did not rise to the occasion. Erasmus Reinhold could have been his successor, but died prematurely. The first of the great successors was Tycho Brahe, followed by his erstwhile co-worker, Johannes Kepler.

Copernicanism

- See also: Catholic Church and science

At original publication, Copernicus' epoch-making book caused only mild controversy, and provoked no fierce sermons about contradicting Holy Scripture. It was only three years later, in 1546, that a Dominican, Giovanni Maria Tolosani, denounced the theory in an appendix to a work defending the absolute truth of Scripture. He also noted that the Master of the Sacred Palace (i.e., the Catholic Church's chief censor), Bartolomeo Spina, a friend and fellow Dominican, had planned to condemn De revolutionibus but had been prevented from doing so by his illness and death.

Arthur Koestler, in his popular book The Sleepwalkers, asserted that Copernicus' book had not been widely read on its first publication. This claim was trenchantly criticised by Edward Rosen, and has been decisively disproved by Owen Gingerich, who examined every surviving copy of the first two editions and found copious marginal notes by their owners throughout many of them. Gingerich published his conclusions in 2004 in The Book Nobody Read.

It has been much debated why it was not until six decades after Spina and Tolosani's attacks on Copernicus's work that the Catholic Church took any official action against it. Proposed reasons have included the personality of Galileo Galilei and the availability of evidence such as telescope observations.

In March 1616, in connection with the Galileo affair, the Roman Catholic Church's Congregation of the Index issued a decree suspending De revolutionibus until it could be "corrected," on the grounds that the supposedly Pythagorean doctrine that the Earth moves and the Sun does not was "false and altogether opposed to Holy Scripture." The same decree also prohibited any work that defended the mobility of the Earth or the immobility of the Sun, or that attempted to reconcile these assertions with Scripture.

On the orders of Pope Paul V, Cardinal Robert Bellarmine gave Galileo prior notice that the decree was about to be issued, and warned him that he could not "hold or defend" the Copernican doctrine. The corrections to De revolutionibus, which omitted or altered nine sentences, were issued four years later, in 1620.

In 1633 Galileo Galilei was convicted of grave suspicion of heresy for "following the position of Copernicus, which is contrary to the true sense and authority of Holy Scripture," and was placed under house arrest for the rest of his life.

The Catholic Church's 1758 Index of Prohibited Books omitted the general prohibition of works defending heliocentrism, but retained the specific prohibitions of the original uncensored versions of De revolutionibus and Galileo's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. Those prohibitions were finally dropped from the 1835 Index.

Nationality

The question of Copernicus' nationality, and indeed whether it is meaningful to ascribe to him a nationality in the modern sense, has been the subject of some discussion.

Historian Michael Burleigh describes the nationality debate as a "totally insignificant battle" between German and Polish scholars during the interwar period.

Astronomer Konrad Rudnicki calls the discussion a "fierce scholarly quarrel in... times of nationalism", and describes Copernicus as an inhabitant of a German-speaking territory belonging to Poland, himself of mixed Polish-German extraction.

According to Czesław Miłosz, the debate is an "absurd" projection of a modern understanding of nationality on Renaissance people, who identified with their home territories rather than with a nation.

Similarly, historian Norman Davies states that Copernicus, as was common for his era, was "largely indifferent" to nationality, being a local patriot who considered himself "Prussian".

Miłosz and Davies both say that despite Copernicus' German-speaking background, his working language was Latin, though according to Davies there is evidence that Copernicus also knew Polish. Davies concludes: "Taking everything into consideration, there is good reason to regard him both as a German and as a Pole, yet in the sense that modern nationalists understand it, he was neither."

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy describes Copernicus as "the child of a German family was a subject of the Polish crown." Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia Americana, The Columbia Encyclopedia, The Oxford World Encyclopedia, and the Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia identify Copernicus as Polish.

Copernicium

On July 14, 2009, the discoverers, from the Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung in Darmstadt, Germany, of chemical element 112 (temporarily named ununbium) proposed to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry that its permanent name be "copernicium" (symbol Cn). "After we had named elements after our city and our state, we wanted to make a statement with a name that was known to everyone," said Hofmann. "We didn't want to select someone who was a German. We were looking world-wide." On the 537th anniversary of his birthday the official naming was released to the public.

Veneration

Copernicus is honored, together with Johannes Kepler, in the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA), with a feast day on May 23.

See also

Notes

- Nicolaus Copernicus Gesamtausgabe: Urkunden, Akten und Nachrichten: Texte und Übersetzungen, ISBN 3-05-003009-7, pp.23ff. (online); Marian Biskup: Regesta Copernicana (calendar of Copernicus' Papers), Ossolineum, 1973, p.32 (online). This spelling of the surname is rendered in many publications (Auflistung)

- Copernicus was not, however, the first to propose some form of heliocentric system. A Greek mathematician and astronomer, Aristarchus of Samos, had already done so as early as the third century BCE. Nevertheless, there is little evidence that he ever developed his ideas beyond a very basic outline (Dreyer, 1953, pp. 135–48; Linton, 2004, p. 39).

- A self-portrait helped confirm the identity of his cranium when it was discovered at Frombork Cathedral in 2008. Kraków's Jagiellonian University has a 17th-century copy of Copernicus' 16th-century self-portrait. "Copernicus," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th ed., 2005, vol. 16, p. 760.

- Dreyer (1953, pp. 40–52); Linton (2004, p. 20).

- Dreyer (1953, pp. 123–35); Linton (2004, p. 24).

- Archimedes refers to Aristarchus's book in The Sand Reckoner. Heath's (1913, p.302) translation of the relevant passage reads: "You are aware that 'universe' is the name given by most astronomers to the sphere the center of which is the center of the Earth, while its radius is equal to the straight line between the center of the Sun and the center of the Earth. This is the common account as you have heard from astronomers. But Aristarchus has brought out a book consisting of certain hypotheses, wherein it appears, as a consequence of the assumptions made, that the universe is many times greater than the 'universe' just mentioned. His hypotheses are that the fixed stars and the Sun remain unmoved, that the Earth revolves about the Sun on the circumference of a circle, the Sun lying in the middle of the orbit, and that the sphere of the fixed stars, situated about the same center as the Sun, is so great that the circle in which he supposes the Earth to revolve bears such a proportion to the distance of the fixed stars as the center of the sphere bears to its surface." The bracketed insertion is in Heath's translation.

- Tassoul, Jean-Louis & Monique (2004). Concise History of Solar and Stellar Physics. Princeton University.

- Dreyer (1953, pp. 314–15).

- Hoskin, Michael A. (1999). The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-521-57600-8.

- Rosen (2004, pp. 58–59).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Repcheckwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Rosen (1995, pp.151–59)

- Rosen (1995, p.158)

- Koestler (1959, p.191)

- Rosen (1995, pp.187–192), originally published in 1967 in Saggi su Galileo Galilei . Rosen is particularly scathing about this and other statements in The Sleepwalkers which he criticises as inaccurate.

- Gingerich (2004), DeMarco (2004)

- In fact, in the Pythagorean cosmological system the Sun was not motionless.

- Decree of the General Congregation of the Index, March 5, 1616, translated from the Latin by Finocchiaro (1989, pp.148-149). An on-line copy of Finocchiaro's translation has been made available by Gagné (2005).

- Fantoli (2005, pp.118–19); Finocchiaro (1989, pp.148, 153). On-line copies of Finocchiaro's translations of the relevant documents, Inquisition Minutes of 25 February, 1616 and Cardinal Bellarmine's certificate of 26 May, 1616, have been made available by Gagné (2005). This notice of the decree would not have prevented Galileo from discussing heliocentrism solely as a mathematical hypothesis, but a stronger formal injunction (Finocchiaro, 1989, p.147-148) not to teach it "in any way whatever, either orally or in writing", allegedly issued to him by the Commissary of the Holy Office, Father Michelangelo Segizzi, would certainly have done so (Fantoli, 2005, pp.119–20, 137). There has been much controversy over whether the copy of this injunction in the Vatican archives is authentic; if so, whether it was ever issued; and if so, whether it was legally valid (Fantoli, 2005, pp.120–43).

- Catholic Encyclopedia.

- From the Inquisition's sentence of June 22, 1633 (de Santillana, 1976, pp.306-10; Finocchiaro 1989, pp. 287-91)

- Heilbron (2005, p. 307); Coyne (2005, p. 347).

- McMullin (2005, p. 6); Coyne (2005, pp. 346-47).

- Burleigh, Michael (1988). Germany turns eastwards. A study of Ostforschung in the Third Reich. CUP Archive. pp. 60, 133, 280. ISBN 0521351200.

- Rudnicki, Konrad (2006). "The Genuine Copernican Cosmological Principle". Southern Cross Review: note 2. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Miłosz, Czesław (1983). The history of Polish literature (2 ed.). University of California Press. p. 37. ISBN 0520044770.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2005). God's playground. A History of Poland in Two Volumes. Vol. II. Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 0199253404.

- "Nicolaus Copernicus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- "Copernicus, Nicolaus". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- "Copernicus, Nicolaus", Encyclopedia Americana, 1986, vol. 7, pp. 755–56.

- "Nicholas Copernicus", The Columbia Encyclopedia, sixth edition, 2008. Encyclopedia.com. 18 July 2009.

- "Copernicus, Nicolaus", The Oxford World Encyclopedia, Oxford University Press, 1998.

- "Nicolaus Copernicus, Polish astronomer". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Microsoft. 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-11-01. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - July 14, 2009 - Element 112 shall be named “copernicium”, http://www.popsci.com/

- Renner, Terrence (2010-02-20). "Element 112 is Named Copernicium". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- Calendar of the Church Year according to the Episcopal Church

References

- Armitage, Angus (1951). The World of Copernicus. New York, NY: Mentor Books. ISBN 0-8464-0979-8.

- Barbara Bieńkowska (1973). The Scientific World of Copernicus: On the Occasion of the 500th Anniversary of His Birth, 1473–1973. Springer. ISBN 9027703531.

- Coyne, George V., S.J. (2005). The Church's Most Recent Attempt to Dispel the Galileo Myth. In McMullin (2005, pp.340–59).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Davies, Norman, God's Playground: A History of Poland, 2 vols., New York, Columbia University Press, 1982, ISBN 0-231-04327-9.

- DeMarco, Peter (2004-04-13). "Book quest took him around the globe". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- Dobrzycki, Jerzy, and Leszek Hajdukiewicz, "Kopernik, Mikołaj," Polski słownik biograficzny (Polish Biographical Dictionary), vol. XIV, Wrocław, Polish Academy of Sciences, 1969, pp. 3–16.

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil (1953) . A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler. New York, NY: Dover Publications.

- Fantoli, Annibale (2005). The Disputed Injunction and its Role in Galileo's Trial. In McMullin (2005, pp.117–49).

- Finocchiaro, Maurice A. (1989). The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06662-6.

- Gagné, Marc (2005). "Texts from The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History edited and translated by Maurice A. Finocchiaro". West Chester University course ESS 362/562 in History of Astronomy. Retrieved 2008-01-15. (Extracts from Finocchiaro (1989))

- Gingerich, Owen (2004). The Book Nobody Read. London: William Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-01315-3.

- Goodman, David C. (1991). The Rise of Scientific Europe, 1500-1800. Hodder Arnold H&S. ISBN 0-340-55861-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Heath, Sir Thomas (1913). Aristarchus of Samos, the ancient Copernicus ; a history of Greek astronomy to Aristarchus, together with Aristarchus's Treatise on the sizes and distances of the sun and moon : a new Greek text with translation and notes. London: Oxford University Press.

- Heilbron, John L. (2005). Censorship of Astronomy in Italy after Galileo. In McMullin (2005, pp.279–322).

- Hoskin, Michael A., The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy, Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-57600-8.

- Koestler, Arthur (1963) . The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. New York, NY: Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 0448001594. Original edition published by Hutchinson (1959, London)

- Koeppen, Hans; et al. (1973). Nicolaus Copernicus zum 500. Geburtstag. Böhlau Verlag. ISBN 3-412-83573-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Koyré, Alexandre (1973). The Astronomical Revolution: Copernicus – Kepler – Borelli. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0504-1.

- Kuhn, Thomas (1957). The Copernican Revolution: Planetary Astronomy in the Development of Western Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 535467.

- Lindberg, David C.; Numbers, Ronald L. (1986). "Beyond War and Peace: A Reappraisal of the Encounter between Christianity and Science". Church History. 55 (3). Cambridge University Press: 338–354. doi:10.2307/3166822.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Linton, Christopher M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein—A History of Mathematical Astronomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82750-8.

- Manetho; Ptolemy (1964) . Manetho Ptolemy Tetrabiblos. Loeb Classical Library edition, translated by W.G.Waddell and F.E.Robbins Ph.D. London: William Heinemann.

- McMullin, Ernan, ed. (2005). The Church and Galileo. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-03483-4.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Miłosz, Czesław, The History of Polish Literature, second edition, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1969, ISBN 0-520-04477-0.

- Ptolemy, Claudius (1964) . Tetrabiblos. Loeb Classical Library edition, translated by F.E.Robbins Ph.D. London: William Heinemann.

- Rabin, Sheila (2005). "Copernicus". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2005 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- Repcheck, Jack (2007). Copernicus' Secret: How the Scientific Revolution Began. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-8951-X.

- Rosen, Edward (1995). Copernicus and his Successors. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 1 85285 071 X.

- Rosen, Edward (translator) (2004) . Three Copernican Treatises:The Commentariolus of Copernicus; The Letter against Werner; The Narratio Prima of Rheticus (Second Edition, revised ed.). New York, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486436055.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1997) . Inventing the Flat Earth—Columbus and Modern Historians. New York, NY: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-95904-X.

- de Santillana, Giorgio (1976—Midway reprint) . The Crime of Galileo. Chicago, Ill: Universtiy of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-73481-1.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages 1000-1500. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295972904.

- Thoren, Victor E. (1990). The Lord of Uraniborg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-35158-8. (A biography of Danish astronomer and alchemist Tycho Brahe.)

Further reading

- Danielson, Dennis Richard (2006). The First Copernican: Georg Joachim Rheticus and the Rise of the Copernican Revolution. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 0-8027-1530-3.

- Prowe, Leopold (1884). Nicolaus Coppernicus (in German). Berlin: Weidmannsche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

- Nicolaus Copernicus Gesamtausgabe (Nicolaus Copernicus Complete Edition; in German and Latin; 9 volumes, 1974–2004), various editors, Berlin, Akademie Verlag. A large collection of writings by and about Copernicus.

- Nicolaus Copernicus Gesamtausgabe: Biographies and Portraits of Copernicus from 16th to 18th century, Biographia Copernicana, 2004, ISBN 3-05-003848-9

- Schmauch, Hans (1957), "Copernicus, Nicolaus", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 3, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 348–355

- Bruhns, Christian (1876), "Copernicus, Nicolaus", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 4, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 461–469

External links

- Primary Sources

- Works by Nicolaus Copernicus at Project Gutenberg

- De Revolutionibus, autograph manuscript — Full digital facsimile, Jagiellonian University

- Template:Pl icon Polish translations of letters written by Copernicus in Latin or German

- General

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Nicolaus Copernicus", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Copernicus in Torun

- Nicolaus Copernicus Museum in Frombork

- Portraits of Copernicus: Copernicus's face reconstructed; Portrait; Nicolaus Copernicus

- Copernicus and Astrology — Cambridge University: Copernicus had – of course – teachers with astrological activities and his tables were later used by astrologers.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Find-A-Grave profile for Nicolaus Copernicus

- 'Body of Copernicus' identified — BBC article including image of Copernicus using facial reconstruction based on located skull

- Copernicus and Astrology

- Nicolaus Copernicus on the 1000 Polish Zloty banknote.

- Parallax and the Earth's orbit

- Copernicus's model for Mars

- Retrograde Motion

- Copernicus's explanation for retrograde motion

- Geometry of Maximum Elongation

- Copernican Model

- Portraits of Nicolaus Copernicus

- About De Revolutionibus

- The Copernican Universe from the De Revolutionibus

- De Revolutionibus, 1543 first edition — Full digital facsimile, Lehigh University

- The front page of the De Revolutionibus

- The text of the De Revolutionibus

- A java applet about Retrograde Motion

- The Antikythera Calculator (Italian and English versions)

- Pastore Giovanni, Antikythera e i Regoli calcolatori, Rome, 2006, privately published

- Legacy

- Template:It icon Copernicus in Bologna — in Italian

- Chasing Copernicus: The Book Nobody Read — Was One of the Greatest Scientific Works Really Ignored? All Things Considered. NPR

- Copernicus and his Revolutions — A detailed critique of the rhetoric of De Revolutionibus

- Article which discusses Copernicus's debt to the Arabic tradition

- Prizes

- Nicolaus Copernicus Prize, founded by the City of Kraków, awarded since 1995

- German-Polish cooperation

- Template:En icon Template:De icon Template:Pl icon German-Polish "Copernicus Prize" awarded to German and Polish scientists (DFG website) (FNP website)

- Template:En icon Template:De icon Template:Pl icon Büro Kopernikus - An initiative of German Federal Cultural Foundation

- Template:De icon Template:Pl icon German-Polish school project on Copernicus

- Astronomers

- 16th-century astronomers

- 16th-century Latin-language writers

- 16th-century mathematicians

- Alumni of Jagiellonian University

- University of Padua alumni

- University of Bologna alumni

- University of Ferrara alumni

- History of astronomy

- Renaissance people

- Astronomers from Royal Prussia

- People from Royal Prussia

- People from Toruń

- German astronomers

- German philosophers

- German economists

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- Polish astronomers

- Polish philosophers

- Polish economists

- Polish Roman Catholics

- Religion and science

- Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Walhalla enshrinees

- Canons of Warmia

- Burials at Frombork Cathedral

- 1473 births

- 1543 deaths

- Anglican saints