This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 125.19.209.46 (talk) at 05:59, 26 January 2012 (→Politics). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:59, 26 January 2012 by 125.19.209.46 (talk) (→Politics)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the continent. For other uses, see Antarctica (disambiguation).Antarctica

This map uses an orthographic projection, near-polar aspect. The South Pole is near the center, where longitudinal lines converge.

| Area (Overall)

|

14,000,000 km (5,400,000 sq mi) 280,000 km (110,000 sq mi) 13,720,000 km (5,300,000 sq mi) |

|---|---|

| Population (permanent) (non-permanent) |

7th 0 approx. 1,000 - 5,000 |

| Dependencies | 4 |

| Official Territorial claims | Antarctic Treaty System 8 |

| Reserved the right to make claims | 2 |

| Time Zones | None UTC-03:00 (Graham Land only) |

| Internet Top-level domain | .aq |

| Calling Code | Dependent on the parent country of each base. (One such is +672.) |

Antarctica (pronounced /ænˈtɑːrtkə/ or /ænˈtɑrktɨkə/ ) is Earth's southernmost continent, encapsulating the South Pole. It is situated in the Antarctic region of the Southern Hemisphere, almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle, and is surrounded by the Southern Ocean. At 14.0 million km (5.4 million sq mi), it is the fifth-largest continent in area after Asia, Africa, North America, and South America. For comparison, Antarctica is nearly twice the size of Australia. About 98% of Antarctica is covered by ice that averages at least 1 mile (1.6 km) in thickness.

Antarctica, on average, is the coldest, driest, and windiest continent, and has the highest average elevation of all the continents. Antarctica is considered a desert, with annual precipitation of only 200 mm (8 inches) along the coast and far less inland. The temperature in Antarctica has reached −89 °C (−129 °F). There are no permanent human residents, but anywhere from 1,000 to 5,000 people reside throughout the year at the research stations scattered across the continent. Only cold-adapted organisms survive there, including many types of algae, animals (for example mites, nematodes, penguins, seals and tardigrades), bacteria, fungi, plants, and protista. Vegetation where it occurs is tundra.

Although myths and speculation about a Terra Australis ("Southern Land") date back to antiquity, the first confirmed sighting of the continent is commonly accepted to have occurred in 1820 by the Russian expedition of Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev. The continent, however, remained largely neglected for the rest of the 19th century because of its hostile environment, lack of resources, and isolation. The Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1959 by 12 countries; to date, 47 countries have signed the treaty. The treaty prohibits military activities and mineral mining, prohibits nuclear explosions and nuclear power, supports scientific research, and protects the continent's ecozone. Ongoing experiments are conducted by more than 4,000 scientists from many nations.

Etymology

The first formal use of the name "Antarctica" as a continental name in the 1890s is attributed to the Scottish cartographer John George Bartholomew. The name Antarctica is the romanized version of the Greek compound word ἀνταρκτική (antarktiké), feminine of ἀνταρκτικός (antarktikos), meaning "opposite to the Arctic", "opposite to the north".

History

Main article: History of Antarctica See also: List of Antarctic expeditionsBelief in the existence of a Terra Australis – a vast continent in the far south of the globe to "balance" the northern lands of Europe, Asia and North Africa – has existed since the times of Ptolemy (1st century AD), who suggested the idea to preserve the symmetry of all known landmasses in the world. Even in the late 17th century, after explorers had found that South America and Australia were not part of the fabled "Antarctica", geographers believed that the continent was much larger than its actual size.

European maps continued to show this hypothetical land until Captain James Cook's ships, HMS Resolution and Adventure, crossed the Antarctic Circle on 17 January 1773, in December 1773 and again in January 1774. Cook came within about 75 miles (121 km) of the Antarctic coast before retreating in the face of field ice in January 1773. The first confirmed sighting of Antarctica can be narrowed down to the crews of ships captained by three individuals. According to various organizations (the National Science Foundation, NASA, the University of California, San Diego, and other sources), ships captained by three men sighted Antarctica in 1820: Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen (an Estonian-born captain in the Imperial Russian Navy), Edward Bransfield (an Irish-born captain in the Royal Navy), and Nathaniel Palmer (an American sealer out of Stonington, Connecticut). Von Bellingshausen saw Antarctica on 27 January 1820, three days before Bransfield sighted land, and ten months before Palmer did so in November 1820. On that day the two-ship expedition led by Von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev reached a point within 32 km (20 mi) of the Antarctic mainland and saw ice fields there. The first documented landing on mainland Antarctica was by the American sealer John Davis in West Antarctica on 7 February 1821, although some historians dispute this claim.

On 22 January 1840, two days after the discovery of the coast west of the Balleny Islands, some members of the crew of the 1837-40 expedition of Jules Dumont d'Urville disembarked on the highest islet, of a group of rocky islands about 4 km from Cape Geodesie on the coast of Adélie land where they took some mineral, algae and animal samples.

In December 1839, as part of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–42 conducted by the United States Navy (sometimes called the "Ex. Ex.", or "the Wilkes Expedition"), an expedition sailed from Sydney, Australia, into the Antarctic Ocean, as it was then known, and reported the discovery "of an Antarctic continent west of the Balleny Islands" on 25 January 1840. That part of Antarctica was later named "Wilkes Land", a name it maintains to this day.

Explorer James Clark Ross passed through what is now known as the Ross Sea and discovered Ross Island (both of which were named for him) in 1841. He sailed along a huge wall of ice that was later named the Ross Ice Shelf. Mount Erebus and Mount Terror are named after two ships from his expedition: HMS Erebus and Terror. Mercator Cooper landed in East Antarctica on 26 January 1853.

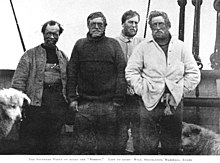

During the Nimrod Expedition led by Ernest Shackleton in 1907, parties led by Edgeworth David became the first to climb Mount Erebus and to reach the South Magnetic Pole. Douglas Mawson, who assumed the leadership of the Magnetic Pole party on their perilous return, went on to lead several expeditions until retiring in 1931. In addition, Shackleton himself and three other members of his expedition made several firsts in December 1908 – February 1909: they were the first humans to traverse the Ross Ice Shelf, the first to traverse the Transantarctic Mountain Range (via the Beardmore Glacier), and the first to set foot on the South Polar Plateau. An expedition led by Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen from the ship Fram became the first to reach the geographic South Pole on 14 December 1911, using a route from the Bay of Whales and up the Axel Heiberg Glacier. One month later, the doomed Scott Expedition reached the pole.

Richard E. Byrd led several voyages to the Antarctic by plane in the 1930s and 1940s. He is credited with implementing mechanized land transport on the continent and conducting extensive geological and biological research. However, it was not until 31 October 1956 that anyone set foot on the South Pole again; on that day a U.S. Navy group led by Rear Admiral George J. Dufek successfully landed an aircraft there.

The first person to sail single-handed to Antarctica was the New Zealander David Henry Lewis, in a 10-meter steel sloop Ice Bird.

Geography

Main article: Geography of Antarctica See also: Extreme points of Antarctica and List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

Centered asymmetrically around the South Pole and largely south of the Antarctic Circle, Antarctica is the southernmost continent and is surrounded by the Southern Ocean; alternatively, it may be considered to be surrounded by the southern Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, or by the southern waters of the World Ocean. It covers more than 14,000,000 km (5,400,000 sq mi), making it the fifth-largest continent, about 1.3 times as large as Europe. The coastline measures 17,968 km (11,165 mi) and is mostly characterized by ice formations, as the following table shows:

| Type | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Ice shelf (floating ice front) | 44% |

| Ice walls (resting on ground) | 38% |

| Ice stream/outlet glacier (ice front or ice wall) | 13% |

| Rock | 5% |

| Total | 100% |

Antarctica is divided in two by the Transantarctic Mountains close to the neck between the Ross Sea and the Weddell Sea. The portion west of the Weddell Sea and east of the Ross Sea is called West Antarctica and the remainder East Antarctica, because they roughly correspond to the Western and Eastern Hemispheres relative to the Greenwich meridian.

About 98% of Antarctica is covered by the Antarctic ice sheet, a sheet of ice averaging at least 1.6 km (1.0 mi) thick. The continent has about 90% of the world's ice (and thereby about 70% of the world's fresh water). If all of this ice were melted, sea levels would rise about 60 m (200 ft). In most of the interior of the continent, precipitation is very low, down to 20 mm (0.8 in) per year; in a few "blue ice" areas precipitation is lower than mass loss by sublimation and so the local mass balance is negative. In the dry valleys the same effect occurs over a rock base, leading to a desiccated landscape.

West Antarctica is covered by the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The sheet has been of recent concern because of the real, if small, possibility of its collapse. If the sheet were to break down, ocean levels would rise by several metres in a relatively geologically short period of time, perhaps a matter of centuries. Several Antarctic ice streams, which account for about 10% of the ice sheet, flow to one of the many Antarctic ice shelves.

East Antarctica lies on the Indian Ocean side of the Transantarctic Mountains and comprises Coats Land, Queen Maud Land, Enderby Land, Mac. Robertson Land, Wilkes Land and Victoria Land. All but a small portion of this region lies within the Eastern Hemisphere. East Antarctica is largely covered by the East Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Vinson Massif, the highest peak in Antarctica at 4,892 m (16,050 ft), is located in the Ellsworth Mountains. Antarctica contains many other mountains, both on the main continent and the surrounding islands. Located on Ross Island, Mount Erebus is the world's southernmost active volcano. Another well-known volcano is found on Deception Island, which is famous for a giant eruption in 1970. Minor eruptions are frequent and lava flow has been observed in recent years. Other dormant volcanoes may potentially be active. In 2004, an underwater volcano was found in the Antarctic Peninsula by American and Canadian researchers. Recent evidence shows this unnamed volcano may be active.

Antarctica is home to more than 70 lakes that lie at the base of the continental ice sheet. Lake Vostok, discovered beneath Russia's Vostok Station in 1996, is the largest of these subglacial lakes. It was once believed that the lake had been sealed off for 500,000 to one million years but a recent survey suggests that, every so often, there are large flows of water from one lake to another.

There is some evidence, in the form of ice cores drilled to about 400 m (1,300 ft) above the water line, that Lake Vostok's waters may contain microbial life. The frozen surface of the lake shares similarities with Jupiter's moon Europa. If life is discovered in Lake Vostok, this would strengthen the argument for the possibility of life on Europa. On 7 February 2008, a NASA team embarked on a mission to Lake Untersee, searching for extremophiles in its highly alkaline waters. If found, these resilient creatures could further bolster the argument for extraterrestrial life in extremely cold, methane-rich environments.

Geology

Main article: Geology of AntarcticaGeological history and paleontology

More than 170 million years ago, Antarctica was part of the supercontinent Gondwana. Over time, Gondwana gradually broke apart and Antarctica as we know it today was formed around 25 million years ago.

Paleozoic era (540–250 Ma)

During the Cambrian period, Gondwana had a mild climate. West Antarctica was partially in the Northern Hemisphere, and during this period large amounts of sandstones, limestones and shales were deposited. East Antarctica was at the equator, where sea floor invertebrates and trilobites flourished in the tropical seas. By the start of the Devonian period (416 Ma), Gondwana was in more southern latitudes and the climate was cooler, though fossils of land plants are known from this time. Sand and silts were laid down in what is now the Ellsworth, Horlick and Pensacola Mountains. Glaciation began at the end of the Devonian period (360 Ma), as Gondwana became centered around the South Pole and the climate cooled, though flora remained. During the Permian period, the plant life became dominated by fern-like plants such as Glossopteris, which grew in swamps. Over time these swamps became deposits of coal in the Transantarctic Mountains. Towards the end of the Permian period, continued warming led to a dry, hot climate over much of Gondwana.

Mesozoic era (250–65 Ma)

As a result of continued warming, the polar ice caps melted and much of Gondwana became a desert. In Eastern Antarctica, the seed fern became established, and large amounts of sandstone and shale were laid down at this time. Synapsids, commonly known as "mammal-like reptiles", were common in Antarctica during the Late Permian and Early Triassic and included forms such as Lystrosaurus. The Antarctic Peninsula began to form during the Jurassic period (206–146 Ma), and islands gradually rose out of the ocean. Ginkgo trees and cycads were plentiful during this period. In West Antarctica, coniferous forests dominated through the entire Cretaceous period (146–65 Ma), though Southern beech began to take over at the end of this period. Ammonites were common in the seas around Antarctica, and dinosaurs were also present, though only three Antarctic dinosaur genera (Cryolophosaurus and Glacialisaurus, from the Hanson Formation, and Antarctopelta) have been described to date. It was during this period that Gondwana began to break up.

Gondwanaland breakup (160–23 Ma)

The cooling of Antarctica occurred stepwise, as the continental spread changed the oceanic currents from longitudinal equator-to-pole temperature-equalizing currents to latitudinal currents that preserved and accentuated latitude temperature differences.

Africa separated from Antarctica around 160 Ma, followed by the Indian subcontinent, in the early Cretaceous (about 125 Ma). About 65 Ma, Antarctica (then connected to Australia) still had a tropical to subtropical climate, complete with a marsupial fauna. About 40 Ma Australia-New Guinea separated from Antarctica, so that latitudinal currents could isolate Antarctica from Australia, and the first ice began to appear. During the Eocene-Oligocene extinction event about 34 million years ago, CO2 levels have been found to be about 760 ppm and had been decreasing from earlier levels in the thousands of ppm. Around 23 Ma, the Drake Passage opened between Antarctica and South America, resulting in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current that completely isolated the continent. Models of the changes suggest that declining CO2 levels became more important. The ice began to spread, replacing the forests that then covered the continent. Since about 15 Ma, the continent has been mostly covered with ice, with the Antarctic ice cap reaching its present extension around 6 Ma.

Geology of present-day Antarctica

The geological study of Antarctica has been greatly hindered by the fact that nearly all of the continent is permanently covered with a thick layer of ice. However, new techniques such as remote sensing, ground-penetrating radar and satellite imagery have begun to reveal the structures beneath the ice.

Geologically, West Antarctica closely resembles the Andes mountain range of South America. The Antarctic Peninsula was formed by uplift and metamorphism of sea bed sediments during the late Paleozoic and the early Mesozoic eras. This sediment uplift was accompanied by igneous intrusions and volcanism. The most common rocks in West Antarctica are andesite and rhyolite volcanics formed during the Jurassic period. There is also evidence of volcanic activity, even after the ice sheet had formed, in Marie Byrd Land and Alexander Island. The only anomalous area of West Antarctica is the Ellsworth Mountains region, where the stratigraphy is more similar to the eastern part of the continent.

East Antarctica is geologically varied, dating from the Precambrian era, with some rocks formed more than 3 billion years ago. It is composed of a metamorphic and igneous platform which is the basis of the continental shield. On top of this base are various modern rocks, such as sandstones, limestones, coal and shales laid down during the Devonian and Jurassic periods to form the Transantarctic Mountains. In coastal areas such as Shackleton Range and Victoria Land some faulting has occurred.

The main mineral resource known on the continent is coal. It was first recorded near the Beardmore Glacier by Frank Wild on the Nimrod Expedition, and now low-grade coal is known across many parts of the Transantarctic Mountains. The Prince Charles Mountains contain significant deposits of iron ore. The most valuable resources of Antarctica lie offshore, namely the oil and natural gas fields found in the Ross Sea in 1973. Exploitation of all mineral resources is banned until 2048 by the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty.

Climate

Main article: Climate of Antarctica

Antarctica is the coldest place on Earth. The coldest natural temperature ever recorded on Earth was −89.2 °C (−128.6 °F) at the Russian Vostok Station in Antarctica on 21 July 1983. For comparison, this is 11 °C (20 °F) colder than subliming dry ice. Antarctica is a frozen desert with little precipitation; the South Pole itself receives less than 10 cm (4 in) per year, on average. Temperatures reach a minimum of between −80 °C (−112 °F) and −90 °C (−130 °F) in the interior in winter and reach a maximum of between 5 °C (41 °F) and 15 °C (59 °F) near the coast in summer. Sunburn is often a health issue as the snow surface reflects almost all of the ultraviolet light falling on it.

East Antarctica is colder than its western counterpart because of its higher elevation. Weather fronts rarely penetrate far into the continent, leaving the center cold and dry. Despite the lack of precipitation over the central portion of the continent, ice there lasts for extended time periods. Heavy snowfalls are not uncommon on the coastal portion of the continent, where snowfalls of up to 1.22 metres (48 in) in 48 hours have been recorded.

At the edge of the continent, strong katabatic winds off the polar plateau often blow at storm force. In the interior, however, wind speeds are typically moderate. During summer, more solar radiation reaches the surface during clear days at the South Pole than at the equator because of the 24 hours of sunlight each day at the Pole.

Antarctica is colder than the Arctic for two reasons. First, much of the continent is more than 3 kilometres (2 mi) above sea level, and temperature decreases with elevation. Second, the Arctic Ocean covers the north polar zone: the ocean's relative warmth is transferred through the icepack and prevents temperatures in the Arctic regions from reaching the extremes typical of the land surface of Antarctica. Given the latitude, long periods of constant darkness or constant sunlight create climates unfamiliar to human beings in much of the rest of the world.

The aurora australis, commonly known as the southern lights, is a glow observed in the night sky near the South Pole created by the plasma-full solar winds that pass by the Earth. Another unique spectacle is diamond dust, a ground-level cloud composed of tiny ice crystals. It generally forms under otherwise clear or nearly clear skies, so people sometimes also refer to it as clear-sky precipitation. A sun dog, a frequent atmospheric optical phenomenon, is a bright "spot" beside the true sun.

Population

See also: Demographics of Antarctica and Research stations of Antarctica

Antarctica has no permanent residents, but a number of governments maintain permanent manned research stations throughout the continent. The number of people conducting and supporting scientific research and other work on the continent and its nearby islands varies from about 1,000 in winter to about 5,000 in the summer. Many of the stations are staffed year-round, the winter-over personnel typically arriving from their home countries for a one-year assignment. An Orthodox church, Trinity Church, opened in 2004 at the Russian Bellingshausen Station is also manned year-round by one or two priests, who are similarly rotated every year.

The first semi-permanent inhabitants of regions near Antarctica (areas situated south of the Antarctic Convergence) were British and American sealers who used to spend a year or more on South Georgia, from 1786 onward. During the whaling era, which lasted until 1966, the population of that island varied from over 1,000 in the summer (over 2,000 in some years) to some 200 in the winter. Most of the whalers were Norwegian, with an increasing proportion of Britons. The settlements included Grytviken, Leith Harbour, King Edward Point, Stromness, Husvik, Prince Olav Harbour, Ocean Harbour and Godthul. Managers and other senior officers of the whaling stations often lived together with their families. Among them was the founder of Grytviken, Captain Carl Anton Larsen, a prominent Norwegian whaler and explorer who, along with his family, adopted British citizenship in 1910.

The first child born in the southern polar region was Norwegian girl Solveig Gunbjørg Jacobsen, born in Grytviken on 8 October 1913, and her birth was registered by the resident British Magistrate of South Georgia. She was a daughter of Fridthjof Jacobsen, the assistant manager of the whaling station, and of Klara Olette Jacobsen. Jacobsen arrived on the island in 1904 and became the manager of Grytviken, serving from 1914 to 1921; two of his children were born on the island.

Emilio Marcos Palma was the first person born south of the 60th parallel south (the continental limit according to the Antarctic Treaty), as well as the first one born on the Antarctic mainland, in 1978 at Base Esperanza, on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula; his parents were sent there along with seven other families by the Argentine government to determine if family life was suitable on the continent. In 1984, Juan Pablo Camacho was born at the Frei Montalva Station, becoming the first Chilean born in Antarctica. Several bases are now home to families with children attending schools at the station. As of 2009, eleven children were born in Antarctica (south of the 60th parallel south): eight at the Argentinean Esperanza Base and three at the Chilean Frei Montalva Station.

Biodiversity

See also: Antarctic ecozone and Antarctica Microorganisms

Few terrestrial vertebrates live in Antarctica. Invertebrate life includes microscopic mites like the Alaskozetes antarcticus, lice, nematodes, tardigrades, rotifers, krill and springtails. The flightless midge Belgica antarctica, up to 6 millimetres (0.2 in) in size, is the largest purely terrestrial animal in Antarctica. The Snow Petrel is one of only three birds that breed exclusively in Antarctica.

A variety of marine animals exist and rely, directly or indirectly, on the phytoplankton. Antarctic sea life includes penguins, blue whales, orcas, colossal squids and fur seals. The Emperor penguin is the only penguin that breeds during the winter in Antarctica, while the Adélie Penguin breeds farther south than any other penguin. The Rockhopper penguin has distinctive feathers around the eyes, giving the appearance of elaborate eyelashes. King penguins, Chinstrap penguins, and Gentoo Penguins also breed in the Antarctic.

The Antarctic fur seal was very heavily hunted in the 18th and 19th centuries for its pelt by sealers from the United States and the United Kingdom. The Weddell Seal, a "true seal", is named after Sir James Weddell, commander of British sealing expeditions in the Weddell Sea. Antarctic krill, which congregates in large schools, is the keystone species of the ecosystem of the Southern Ocean, and is an important food organism for whales, seals, leopard seals, fur seals, squid, icefish, penguins, albatrosses and many other birds.

A census of sea life carried out during the International Polar Year and which involved some 500 researchers was released in 2010. The research is part of the global Census of Marine Life (CoML) and has disclosed some remarkable findings. More than 235 marine organisms live in both polar regions, having bridged the gap of 12,000 km (7,456 mi). Large animals such as some cetaceans and birds make the round trip annually. More surprising are small forms of life such as mudworms, sea cucumbers and free-swimming snails found in both polar oceans. Various factors may aid in their distribution – fairly uniform temperatures of the deep ocean at the poles and the equator which differ by no more than 5 °C, and the major current systems or marine conveyor belt which transport egg and larvae stages.

The climate of Antarctica does not allow extensive vegetation. A combination of freezing temperatures, poor soil quality, lack of moisture, and lack of sunlight inhibit plant growth. As a result, the diversity of plant life is very small and limited in distribution. Excluding organisms which are not plants (algae and fungi, including lichen-forming species), the flora of the continent largely consists of bryophytes (there are about 100 species of mosses and 25 species of liverworts), with only two species of flowering plants, both found in the Antarctic Peninsula: Deschampsia antarctica (Antarctic hair grass) and Colobanthus quitensis (Antarctic pearlwort). Growth generally occurs in the summer, and only for a few weeks at most.

About 1150 species of fungi have been recorded from Antarctica, of which about 750 are non-lichen-forming and 400 are lichen-forming. Some of these species are cryptoendoliths as a result of evolution under extreme conditions. Seven hundred species of algae exist, most of which are phytoplankton. Multicolored snow algae and diatoms are especially abundant in the coastal regions during the summer. Recently ancient ecosystems consisting of several types of bacteria have been found living trapped deep beneath glaciers. The autotrophic community is made up of mostly protists.

Conservation

The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (also known as the Environmental Protocol or Madrid Protocol) came into force in 1998, and is the main instrument concerned with conservation and management of biodiversity in Antarctica. The Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting is advised on environmental and conservation issues in Antarctica by the Committee for Environmental Protection. A major concern within this committee is the risk to Antarctica from unintentional introduction of non-native species from outside the region.

The passing of the Antarctic Conservation Act (1978) in the U.S. brought several restrictions to U.S. activity on Antarctica. The introduction of alien plants or animals can bring a criminal penalty, as can the extraction of any indigenous species. The overfishing of krill, which plays a large role in the Antarctic ecosystem, led officials to enact regulations on fishing. The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), a treaty that came into force in 1980, requires that regulations managing all Southern Ocean fisheries consider potential effects on the entire Antarctic ecosystem. Despite these new acts, unregulated and illegal fishing, particularly of Patagonian toothfish (marketed as Chilean Sea Bass in the U.S.), remains a serious problem. The illegal fishing of toothfish has been increasing, with estimates of 32,000 tonnes (35,300 short tons) in 2000.

Politics

Antarctica has no government, although various countries claim sovereignty in certain regions. While a few of these countries have mutually recognised each other's claims, the validity of these claims is generally not recognised universally.

New claims on Antarctica have been suspended since 1959 and the continent is considered politically neutral. Its status is regulated by the 1959 Antarctic Treaty and other related agreements, collectively called the Antarctic Treaty System.

Economy

Main article: Economy of AntarcticaAlthough coal, hydrocarbons, iron ore, platinum, copper, chromium, nickel, gold and other minerals have been found, they have not been in large enough quantities to exploit. The 1991 Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty also restricts a struggle for resources. In 1998, a compromise agreement was reached to place an indefinite ban on mining, to be reviewed in 2048, further limiting economic development and exploitation. The primary economic activity is the capture and offshore trading of fish. Antarctic fisheries in 2000–01 reported landing 112,934 tonnes.

Small-scale "expedition tourism" has existed since 1957 and is currently subject to Antarctic Treaty and Environmental Protocol provisions, but in effect self-regulated by the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO). Not all vessels associated with Antarctic tourism are members of IAATO, but IAATO members account for 95% of the tourist activity. Travel is largely by small or medium ship, focusing on specific scenic locations with accessible concentrations of iconic wildlife. A total of 37,506 tourists visited during the 2006–07 Austral summer with nearly all of them coming from commercial ships. The number is predicted to increase to over 80,000 by 2010.

There has been some concern over the potential adverse environmental and ecosystem effects caused by the influx of visitors. A call for stricter regulations for ships and a tourism quota has been made by some environmentalists and scientists. The primary response by Antarctic Treaty Parties has been to develop, through their Committee for Environmental Protection and in partnership with IAATO, "site use guidelines" setting landing limits and closed or restricted zones on the more frequently visited sites. Antarctic sight seeing flights (which did not land) operated out of Australia and New Zealand until the fatal crash of Air New Zealand Flight 901 in 1979 on Mount Erebus, which killed all 257 aboard. Qantas resumed commercial overflights to Antarctica from Australia in the mid-1990s.

Research

See also: Research stations of Antarctica

Each year, scientists from 28 different nations conduct experiments not reproducible in any other place in the world. In the summer more than 4,000 scientists operate research stations; this number decreases to just over 1,000 in the winter. McMurdo Station, which is the largest research station in Antarctica, is capable of housing more than 1,000 scientists, visitors, and tourists.

Researchers include biologists, geologists, oceanographers, physicists, astronomers, glaciologists, and meteorologists. Geologists tend to study plate tectonics, meteorites from outer space, and resources from the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwanaland. Glaciologists in Antarctica are concerned with the study of the history and dynamics of floating ice, seasonal snow, glaciers, and ice sheets. Biologists, in addition to examining the wildlife, are interested in how harsh temperatures and the presence of people affect adaptation and survival strategies in a wide variety of organisms. Medical physicians have made discoveries concerning the spreading of viruses and the body's response to extreme seasonal temperatures. Astrophysicists at Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station study the celestial dome and cosmic microwave background radiation. Many astronomical observations are better made from the interior of Antarctica than from most surface locations because of the high elevation, which results in a thin atmosphere, low temperature, which minimizes the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere, and absence of light pollution, thus allowing for a view of space clearer than anywhere else on Earth. Antarctic ice serves as both the shield and the detection medium for the largest neutrino telescope in the world, built 2 km (1.2 mi) below Amundsen-Scott station.

Since the 1970s, an important focus of study has been the ozone layer in the atmosphere above Antarctica. In 1985, three British Scientists working on data they had gathered at Halley Station on the Brunt Ice Shelf discovered the existence of a hole in this layer. It was eventually determined that the destruction of the ozone was caused by chlorofluorocarbons emitted by human products. With the ban of CFCs in the Montreal Protocol of 1989, it is believed that the ozone hole will close up by around 2065. In September 2006, NASA satellite data showed that the Antarctic ozone hole was the largest on record, covering 27.5 million km (10.6 million sq mi).

On 6 September 2007, Belgian-based International Polar Foundation unveiled the Princess Elisabeth station, the world's first zero-emissions polar science station in Antarctica to research climate change. Costing $16.3 million, the prefabricated station, which is part of International Polar Year, was shipped to the South Pole from Belgium by the end of 2008 to monitor the health of the polar regions. Belgian polar explorer Alain Hubert stated: "This base will be the first of its kind to produce zero emissions, making it a unique model of how energy should be used in the Antarctic." Johan Berte is the leader of the station design team and manager of the project which conducts research in climatology, glaciology and microbiology.

In January 2008, the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) scientists, led by Hugh Corr and David Vaughan, reported (in the journal Nature Geoscience) that 2,200 years ago, a volcano erupted under Antarctica's ice sheet (based on airborne survey with radar images). The biggest eruption in Antarctica in the last 10,000 years, the volcanic ash was found deposited on the ice surface under the Hudson Mountains, close to Pine Island Glacier.

Meteorites

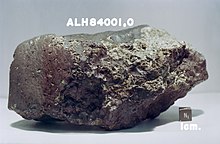

Meteorites from Antarctica are an important area of study of material formed early in the solar system; most are thought to come from asteroids, but some may have originated on larger planets. The first meteorites were found in 1912. In 1969, a Japanese expedition discovered nine meteorites. Most of these meteorites have fallen onto the ice sheet in the last million years. Motion of the ice sheet tends to concentrate the meteorites at blocking locations such as mountain ranges, with wind erosion bringing them to the surface after centuries beneath accumulated snowfall. Compared with meteorites collected in more temperate regions on Earth, the Antarctic meteorites are well-preserved.

This large collection of meteorites allows a better understanding of the abundance of meteorite types in the solar system and how meteorites relate to asteroids and comets. New types of meteorites and rare meteorites have been found. Among these are pieces blasted off the Moon, and probably Mars, by impacts. These specimens, particularly ALH84001 discovered by ANSMET, are at the center of the controversy about possible evidence of microbial life on Mars. Because meteorites in space absorb and record cosmic radiation, the time elapsed since the meteorite hit the Earth can be determined from laboratory studies. The elapsed time since fall, or terrestrial residence age, of a meteorite represents more information that might be useful in environmental studies of Antarctic ice sheets.

In 2006, a team of researchers from Ohio State University used gravity measurements by NASA's GRACE satellites to discover the 300-mile (480 km)-wide Wilkes Land crater, which probably formed about 250 million years ago.

Ice mass and global sea level

See also: Current sea level riseDue to its location at the South Pole, Antarctica receives relatively little solar radiation. This means that it is a very cold continent where water is mostly in the form of ice. Precipitation is low (most of Antarctica is a desert) and almost always in the form of snow, which accumulates and forms a giant ice sheet which covers the land. Parts of this ice sheet form moving glaciers known as ice streams, which flow towards the edges of the continent. Next to the continental shore are many ice shelves. These are floating extensions of outflowing glaciers from the continental ice mass. Offshore, temperatures are also low enough that ice is formed from seawater through most of the year. It is important to understand the various types of Antarctic ice to understand possible effects on sea levels and the implications of global warming.

Sea ice extent expands annually in the Antarctic winter and most of this ice melts in the summer. This ice is formed from the ocean water and floats in the same water and thus does not contribute to rise in sea level. The extent of sea ice around Antarctica has remained roughly constant in recent decades, although the thickness changes are unclear.

Melting of floating ice shelves (ice that originated on the land) does not in itself contribute much to sea-level rise (since the ice displaces only its own mass of water). However it is the outflow of the ice from the land to form the ice shelf which causes a rise in global sea level. This effect is offset by snow falling back onto the continent. Recent decades have witnessed several dramatic collapses of large ice shelves around the coast of Antarctica, especially along the Antarctic Peninsula. Concerns have been raised that disruption of ice shelves may result in increased glacial outflow from the continental ice mass.

On the continent itself, the large volume of ice present stores around 70% of the world's fresh water. This ice sheet is constantly gaining ice from snowfall and losing ice through outflow to the sea. West Antarctica is currently experiencing a net outflow of glacial ice, which will increase global sea level over time. A review of the scientific studies looking at data from 1992 to 2006 suggested that a net loss of around 50 gigatonnes of ice per year was a reasonable estimate (around 0.14 mm of sea level rise). Significant acceleration of outflow glaciers in the Amundsen Sea Embayment may have more than doubled this figure for 2006.

East Antarctica is a cold region with a ground base above sea level and occupies most of the continent. This area is dominated by small accumulations of snowfall which becomes ice and thus eventually seaward glacial flows. The mass balance of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet as a whole is thought to be slightly positive (lowering sea level) or near to balance. However, increased ice outflow has been suggested in some regions.

Effects of global warming

Some of Antarctica has been warming up; particularly strong warming has been noted on the Antarctic Peninsula. A study by Eric Steig published in 2009 noted for the first time that the continent-wide average surface temperature trend of Antarctica is slightly positive at >0.05 °C (0.09 °F) per decade from 1957 to 2006. This study also noted that West Antarctica has warmed by more than 0.1 °C (0.2 °F) per decade in the last 50 years, and this warming is strongest in winter and spring. This is partly offset by fall cooling in East Antarctica. There is evidence from one study that Antarctica is warming as a result of human carbon dioxide emissions. However, the small amount of surface warming in West Antarctica is not believed to be directly affecting the West Antarctic Ice Sheet's contribution to sea level. Instead the recent increases in glacier outflow are believed to be due to an inflow of warm water from the deep ocean, just off the continental shelf. The net contribution to sea level from the Antarctic Peninsula is more likely to be a direct result of the much greater atmospheric warming there.

In 2002 the Antarctic Peninsula's Larsen-B ice shelf collapsed. Between 28 February and 8 March 2008, about 570 square kilometres (220 sq mi) of ice from the Wilkins Ice Shelf on the southwest part of the peninsula collapsed, putting the remaining 15,000 km (5,800 sq mi) of the ice shelf at risk. The ice was being held back by a "thread" of ice about 6 km (4 mi) wide, prior to its collapse on 5 April 2009. According to NASA, the most widespread Antarctic surface melting of the past 30 years occurred in 2005, when an area of ice comparable in size to California briefly melted and refroze; this may have resulted from temperatures rising to as high as 5 °C (41 °F).

Ozone depletion

Each year a large area of low ozone concentration or "ozone hole" grows over Antarctica. This hole covers the whole continent and was at its largest in September 2008, when the longest lasting hole on record remained until the end of December. The hole was detected by scientists in 1985 and has tended to increase over the years of observation. The ozone hole is attributed to the emission of chlorofluorocarbons or CFCs into the atmosphere, which decompose the ozone into other gases.

Some scientific studies suggest that ozone depletion may have a dominant role in governing climatic change in Antarctica (and a wider area of the Southern Hemisphere). Ozone absorbs large amounts of ultraviolet radiation in the stratosphere. Ozone depletion over Antarctica can cause a cooling of around 6 °C in the local stratosphere. This cooling has the effect of intensifying the westerly winds which flow around the continent (the polar vortex) and thus prevents outflow of the cold air near the South Pole. As a result, the continental mass of the East Antarctic ice sheet is held at lower temperatures, and the peripheral areas of Antarctica, especially the Antarctic Peninsula, are subject to higher temperatures, which promote accelerated melting. Models also suggest that the ozone depletion/enhanced polar vortex effect also accounts for the recent increase in sea-ice just offshore of the continent.

See also

Notes

- The word was originally pronounced without /k/, but the spelling pronunciation has become very common. The "c" was originally added to the spelling for etymological reasons and was then misunderstood as not being silent.

References

- ^ United States Central Intelligence Agency (2011). "Antarctica". The World Factbook. Government of the United States. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia; McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Scientific & Technical Terms. "Antarctica". The Free Dictionary. Farlex, Inc. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Definition of Antarctica". Yahoo! Education. Yahoo!. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Crystal, David (2006). The Fight for English. Oxford University Press. p. 172. ISBN 9780199207640.

- Harper, Douglas. "Antarctic". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- National Satellite, Data, and Information Service. "National Geophysical Data Center". Government of the United States. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Joyce, C. Alan (18 January 2007). "The World at a Glance: Surprising Facts". The World Almanac. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- Liddell, Henry George, "Antarktikos", in Crane, Gregory R. (ed.), A Greek–English Lexicon, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, retrieved 16 November 2011

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). - Hince, Bernadette (2000). The Antarctic Dictionary. CSIRO Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 9780957747111.

- "Age of Exploration: John Cook". The Mariners' Museum. Archived from the original on 7 February 2006. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- James Cook, The Journals, edited by Philip Edwards. Penguin Books, 2003, p. 250.

- U.S. Antarctic Program External Panel of the National Science Foundation. "Antarctica—Past and Present" (PDF). Government of the United States. Retrieved 6 February 2006.

- Guthridge, Guy G. "Nathaniel Brown Palmer, 1799–1877". Government of the United States, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 6 February 2006.

- "Palmer Station". University of the City of San Diego. Archived from the original on 10 February 2006. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- "An Antarctic Time Line: 1519–1959". South-Pole.com. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- "Antarctic Explorers Timeline: Early 1800s". Polar Radar for Ice Sheet Measurements (PRISM). Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- Template:Fr icon Proposition de classement du rocher du débarquement dans le cadre des sites et monuments historiques, Antarctic Treaty Consultative meeting 2006, note 4

- Template:Fr icon Voyage au Pôle sud et dans l'Océanie sur les corvettes "l'Astrolabe" et "la Zélée", exécuté par ordre du Roi pendant les années 1837-1838-1839-1840 sous le commandement de M. J. Dumont-d'Urville, capitaine de vaisseau, Paris, Gide publisher, 1842-1846, tome 8, p. 149-152, site of Gallica, BNF.

- "South-Pole – Exploring Antarctica". South-Pole.com. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- "Antarctic Circle – Antarctic First". 9 February 2005. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- "Tannatt William Edgeworth David". Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- "Roald Amundsen". South-Pole.com. Retrieved 9 February 2006.

- "Richard Byrd". 70South.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- "Dates in American Naval History: October". Naval History and Heritage Command. United States Navy. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- Drewry, D. J., ed. (1983). Antarctica: Glaciological and Geophysical Folio. Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge. ISBN 0901021040.

- ^ "How Stuff Works: polar ice caps". howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- British Antarctic Survey. "Volcanoes". Natural Environment Research Council. Retrieved 13 February 2006.

- "Scientists Discover Undersea Volcano Off Antarctica". United States National Science Foundation. Retrieved 13 February 2006.

- Briggs, Helen (19 April 2006). "Secret rivers found in Antarctic". BBC News. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- "Lake Vostok". United States National Science Foundation. Retrieved 13 February 2006. and Bortman, Henry (13 April 2001). "Focus on Europa". NASA. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Extremophile Hunt Begins". Science News. NASA. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Stonehouse, B., ed. (2002). Encyclopedia of Antarctica and the Southern Oceans. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-98665-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Smith, Nathan D.; Pol, Diego (2007). "Anatomy of a basal sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of Antarctica" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 52 (4): 657–674.

- Leslie, Mitch (2007). "The Strange Lives of Polar Dinosaurs". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "New CO2 data helps unlock the secrets of Antarctic formation". Physorg.com. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- DeConto, Robert M.; Pollard, David (16 January 2003). "Rapid Cenozoic glaciation of Antarctica induced by declining atmospheric CO2". Nature. 421 (6920): 245–9. doi:10.1038/nature01290. PMID 12529638. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ Trewby, Mary, ed. (2002). Antarctica: An Encyclopedia from Abbott Ice Shelf to Zooplankton. Firefly Books. ISBN 1-55297-590-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Hudson, Gavin (14 December 2008). "The Coldest Inhabited Places on Earth". Eco Localizer. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ British Antarctic Survey. "Weather in the Antarctic". Natural Environment Research Council. Retrieved 9 February 2006.

- "Flock of Antarctica's Orthodox temple celebrates Holy Trinity Day". Serbian Orthodox Church. 24 May 2004. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- "Владимир Петраков: 'Антарктика – это особая атмосфера, где живут очень интересные люди'" (in Russian). (Vladimir Petrakov: "Antarctic is a special world, full of very interesting people"). Interview with Father Vladimir Petrakov, a priest who twice spent a year at the station.

- Headland, Robert K. (1984). The Island of South Georgia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 12, 130. ISBN 9780521252744. OCLC 473919719.

- Antarctic Treaty, Art. VI ("Area covered by Treaty"): "The provisions of the present Treaty shall apply to the area south of 60° South latitude."

- Old Antarctic Explorers Association. "[title missing]" (PDF). Explorer's Gazette. 9 (1).

- Bone, James (13 November 2007). "The power games that threaten world's last pristine wilderness". The Times.

- "Questions to the Sun for the 2002-03 season". The Antarctic Sun. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 9 February 2006.

- "Registro Civil Base Esperanza" (in Spanish). Argentine Army.

- Corporación de Defensa de la Soberanía. "Derechos soberanos antárticos de Chile" (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- British Antarctic Survey. "Land Animals of Antarctica". Natural Environment Research Council. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- Sandro, Luke. "Antarctic Bestiary – Terrestrial Animals". Laboratory for Ecophysiological Cryobiology, Miami University. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Snow Petrel Pagodroma nivea". BirdLife International. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- "Creatures of Antarctica". Archived from the original on 14 February 2005. Retrieved 6 February 2006.

- Kinver, Mark (15 February 2009). "Ice oceans 'are not poles apart'". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Australian Antarctic Division. "Antarctic Wildlife". Government of Australia. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ British Antarctic Survey. "Plants of Antarctica". Natural Environment Research Council. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Bridge, Paul D.; Spooner, Brian M.; Roberts, Peter J. (2008). "Non-lichenized fungi from the Antarctic region". Mycotaxon. 106: 485–490. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - de Hoog, G.S. (2005). "Fungi of the Antarctic: evolution under extreme conditions". Studies in Mycology. 51: 1–79.

- "Below Antractica". Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- Bridge, Paul D.; Hughes, Kevin. A. (2010). "Conservation issues for Antarctic fungi". Mycologia Balcanica. 7 (1): 73–76.

- Kirby, Alex (15 August 2001). "Toothfish at risk from illegal catches". BBC News. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- "Toothfish". Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- Rogan-Finnemore, Michelle (2005). "What Bioprospecting Means for Antarctica and the Southern Ocean". In Von Tigerstrom, Barbara (ed.). International Law Issues in the South Pacific. Ashgate Publishing. p. 204. ISBN 0-7546-4419-7. "Australia, New Zealand, France, Norway and the United Kingdom reciprocally recognize the validity of each other's claims." – Google Books link: [

- "Final Report, 30th Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting" (DOC). Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- "Politics of Antarctica". Archived from the original on 14 February 2005. Retrieved 5 February 2006.

- Rowe, Mark (11 February 2006). "Tourism threatens Antarctic". London: Telegraph UK. Retrieved 5 February 2006.

- "Science in Antarctica". Antarctic Connection. Retrieved 4 February 2006.

- ^ "NASA and NOAA Announce Ozone Hole is a Double Record Breaker". Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA. 19 October 2006. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- belspo.be – Princess Elisabeth Station

- Black, Richard (20 January 2008). "Ancient Antarctic eruption noted". BBC News. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ "Meteorites from Antarctica". NASA. Retrieved 9 February 2006.

- Gorder, Pam Frost (1 June 2006). "Big Bang in Antarctica—Killer Crater Found Under Ice". Research News.

- "Regional changes in Arctic and Antarctic sea ice". United Nations Environment Programme.

- "All About Sea Ice". National Snow and Ice Data Center.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1029/2004GL020697, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1029/2004GL020697instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.1136776, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.1136776instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ngeo102, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ngeo102instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.10.057, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.epsl.2007.10.057instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/nature07669, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/nature07669instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ngeo338, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ngeo338instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1029/2004GL021284, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1029/2004GL021284instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1029/2008GL034939, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1029/2008GL034939instead. - Pritchard, H., and D. G. Vaughan (2007). "Widespread acceleration of tidewater glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula". Journal of Geophysical Research. 112. doi:10.1029/2006JF000597.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Glasser, Neil (10 February 2008). "Antarctic Ice Shelf Collapse Blamed On More Than Climate Change". ScienceDaily.

- Staff writers (25 March 2008). "Huge Antarctic ice chunk collapses". CNN.com. Cable News Network. Archived from the original on 29 March 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- Staff writers (25 March 2008). "Massive ice shelf on verge of breakup". CNN.com. Cable News Network. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- "Ice Bridge Holding Antarctic Shelf in Place Shatters". The New York Times. Reuters. 5 April 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- "Ice bridge ruptures in Antarctic". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 5 April 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- "Big area of Antarctica melted in 2005". CNN.com. Cable News Network. Reuters. 16 May 2007. Archived from the original on 18 May 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- British Antarctic Survey, Meteorology and Ozone Monitoring Unit. "Antarctic Ozone". Natural Environment Research Council. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin (12 August 2009). "Atmospheric science: Fixing the sky". Nature. 460. Nature Publishing Group: 792–795. doi:10.1038/460792a. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Advanced Supercomputing Division (NAS) (26 June 2001). "The Antarctic Ozone hole". Government of the United States. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- Turner J., Comiso J.C., Marshall G.J., Lachlan-Cope T.A., Bracegirdle T., Maksym T., Meredith M.P., Wang Z., Orr A. (2009). "Non-annular atmospheric circulation change induced by stratospheric ozone depletion and its role in the recent increase of Antarctic sea ice extent". Geophysical Research Letters. 36 (8): L08502. Bibcode:2009GeoRL..3608502T. doi:10.1029/2009GL037524.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Antarctica. on In Our Time at the BBC

- Template:Dmoz

- "Antarctica". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- British Services Antarctic Expedition 2012

- Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, de facto government

- British Antarctic Survey (BAS)

- U.S. Antarctic Program Portal

- Australian Antarctic Division

- South African National Antarctic Programme – Official Website

- Portals on the World – Antarctica from the Library of Congress

- NASA's LIMA (Landsat Image Mosaic of Antarctica) (USGS mirror)

- The Antarctic Sun (Online newspaper of the U.S. Antarctic Program)

- Antarctica and New Zealand (NZHistory.net.nz)

- Journey to Antarctica in 1959 – slideshow by The New York Times

- Listen to Ernest Shackleton describing his 1908 South Pole Expedition

- The recording describing Shackleton's 1908 South Pole Expedition was added to the National Film and Sound Archive's Sounds of Australia Registry in 2007

90°S 0°E / 90°S 0°E / -90; 0

| Antarctica | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography |

|  | ||||||

| History | ||||||||

| Politics | ||||||||

| Society | ||||||||

| Famous explorers | ||||||||

| Continents of Earth | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Polar exploration | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Countries and territories bordering the Indian Ocean | ||

|---|---|---|

| Africa |  | |

| Asia |

| |

| Other | ||

Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: