This is an old revision of this page, as edited by UkPaolo (talk | contribs) at 17:08, 25 April 2006 (rm deleted images). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:08, 25 April 2006 by UkPaolo (talk | contribs) (rm deleted images)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)- This article is about an ethno-linguistic group of peoples who speak Iranian languages. For citizens of the country of Iran see Demographics of Iran.

Iranian peoples (or Iranic peoples) are a group of variously interrelated linguistic, ethnic, and cultural groups mainly living in the Middle East, Central Asia, the Caucasus and parts of South Asia. They speak various Iranian languages, which were once found in a much larger area throughout Eurasia from the Balkans to the borders of China.

The term Iranic peoples is sometimes alternately used in order to avoid confusion as this article does not include Iranian Turks who are often considered a closely related cultural group to Iranian peoples throughout history and in modern times.

Etymology and usage

The term Iranian is derived from the etymological term Iran (lit: Land of the Aryans). The old Proto-Indo-Iranian term 'Arya' is believed to have been one of a series of self-referential terms used by the Aryans, a branch of the Proto-Indo-Europeans, to denote themselves which meant 'noble', at least in the areas populated by Aryans who migrated south from Central Asia and southern Russia. From a linguistic standpoint, the term Iranian or Iranian people is similar, in its usage, to the term Germanic, for example, which includes various peoples who happen to share related Germanic languages such as German, English, and Dutch. Thus, along these lines the Iranian peoples include not only the Persians/Tajiks of Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, but also the Pashtuns, Kurds, Ossetians, Baloch, and other smaller groups. The academic usage of the term Iranian or Iranic peoples is distinct from the state of Iran and its various citizens who are all Iranian by nationality (and thus popularly referred to as Iranians), but not necessarily 'Iranian peoples' by virtue of not being speakers of Iranian languages and generally do not have discernable ties to ancient Iranian tribes.

Roots and classification

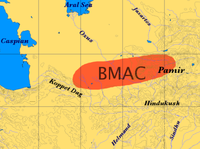

The Iranian languages form a sub-branch of the Indo-Iranian sub-family, which is a branch of the family of Indo-European languages. The Iranian peoples stem from a group specifically known as 'Proto-Iranians', themselves a branch of the Indo-Iranians who split off either in Central Asia or Afghanistan circa. 1800 BCE and are traced to the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. The area between northern Afghanistan to the Aral Sea is hypothesized as the region where the Proto-Iranians first emerged following the separation of the Indo-Iranians. The Saka and Scythian tribes remained mainly in the north and spread as far west as the Balkans and as far east as Xinjiang. Later offshoots related to the Scythians included the Sarmatians who vanished following Slavic and other invasions into southern Russia, the Ukraine, and the Balkans, presumably having been assimilated by other tribes.

Of early writings, there are only scant references from the ancient Assyrians and Babylonians regarding these early Proto-Iranian invaders. Two of the early offshoots of the Proto-Iranians are known: Avestan spoken in Afghanistan and Old Persian spoken in southeastern Iran. The Avestan and the text known as the Avesta are linked to Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism, while Old Persian appears to have been established in writing form following the adoption of cuneiform learned from the Sumerians.

It is from early inscriptions that we first hear mention by an Iranian tribe of their 'Aryan' lineage as with Darius' proclaimation, known as the Behistun Inscription, that he was of Aryan ancestry and that his language, written in cuneiform, was an Aryan language (and this links the Iranian languages to the usage of the term Arya in early Indo-Aryan texts). These ancient Persians recognized three official languages: Elamite, Babylonian, and Old Persian, which suggests a multicultural society. It is not known to what extent other Proto-Iranian tribes referred to themselves as an Aryan people or if the term has the same meaning in other Old Iranian languages.

While the Iranian tribes of the south are better known through their modern counterparts, the tribes which remained largely in the vast Eurasian expanse are mainly known through the references by the ancient Greeks and Persians as well as archaeological research. Herodotus makes references to a nomadic people whom he identifies as the Scythians who dwelt in what is today southern Russia. It is believed that these Scythians were conquered by their eastern cousins the Sarmatians and are mentioned by Strabo as the dominant tribe which controlled the southern Russian steppe. These Sarmatians were also known to the Romans who conquered the western tribes in the Balkans and are known to have sent Sarmatian conscripts, as part of Roman legions, as far west as Roman Britain. Some tribes of Sarmatians are also identified as the Amazons of Greek legend, who were warrior women believed to have lived in a matrilineal society in which both men and women took part in war and whose existence is now supported by recently uncovered archaeological and genetic evidence. The Sarmatians of the east became the Alans who also ventured far and wide, with a branch ending up in Western Europe and North Africa as they accompanied the Germanic Vandals during their migrations. The modern Ossetians are believed to be the sole direct descendants of the Alans as other remnants of the Alans disappeared following Germanic, Hunnic, and ultimately Slavic invasions. Some of the Saka-Scythian tribes in Central Asia would later move further south and invade the Iranian plateau and northwestern India (see Indo-Scythians). Another Iranian tribe related to the Saka-Scythians were the Parni in Central Asia, a tribe that pressured and ultimately overthrew the rule of the Greek Seleucids in Persia and replaced them as the Parthians, a dynasty that ruled Persia during the early centuries of the 1st millennium CE and was the main rival of the Roman Empire in the east. It is surmised that many Iranian tribes were pushed out of Central Asia by the migrations of Turkic tribes emanating out of Siberia.

History and settlement

See also History of Central Asia, History of the Middle East, History of Iran, History of the Kurds, History of Afghanistan, History of Tajikistan, History of Uzbekistan, History of Pakistan, and History of Azerbaijan

Having descended from the Aryans (Proto-Indo-Iranians), the ancient Iranian peoples were separated from the Indo-Aryans, Nuristanis, and Dards in the early 2nd millennium BCE. Ancient Iranian peoples populated the Iranian plateau (for example Medes, Persians, Bactrians, and Parthians), and the steppes north of the Black Sea (for example Scythians, Sarmatians, and Alans) by the 1st millennium BCE.

The ancient Persians established themselves in the western portion of the Iranian plateau and appear to have interacted considerably with the Elamites and Babylonians, while the Medes also intermingled with local Semitic peoples to the west, but remnants of their languages show their common Proto-Iranian roots emphasized by Strabo and Herodotus' analysis of their languages which they believed to be similar to those spoken by the Bactrians and Soghdians in the East. Following the establishment of the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian language spread from Fars to various regions of the empire and the modern dialects of Farsi, Dari, and Tajiki are descended from Old Persian. The Avestan's main impact was religious and liturgical as the early inhabitants of the Persian Empire appear to have adopted the religion of Zoroastrianism. The other prominent Iranian peoples such as the Kurds are surmised to stem from Iranic populations that mixed with Caucasian peoples such as the Hurrians due to some unique qualities found in the Kurdish language that mirror those found in Caucasian languages. The most dominant surviving Eastern Iranians are represented by the Pashtuns whose origins are generally believed to be in southern Afghanistan from whence they began to spread until they reached as far west as Herat and as far east as the Indus. Pashto shows affinities to Bactrian as both languages are believed to be of Middle Iranian origin. The Baloch relate an oral tradition regarding their migration from Aleppo, Syria around roughly the year 1000 CE, whereas linguistic evidence links Baluchi to Kurdish and Zazaki and appears to been heavily influenced by Persian. The modern Ossetians today claim to be the ancestors of the Alano-Sarmatians and their claims are supported by their Northeast Iranian language, while culturally the Ossetes resemble their Caucasian neighbors, the Kabardians, Circassians, and Georgians.

In ancient times, the majority of southern Iranian peoples became adherents of Zoroastrianism, Buddhism (in parts of Afghanistan and Central Asia), Judaism and Christianity (largely amongst the Kurds and Persians living in Iraq). The Ossetes would later adopt Christianity as well with Russian Orthodoxy becoming dominant following their annexation into the Russian Empire while some converted to Islam due to the influence of the Ottomans. Starting with the reign of Omar in 634 CE, Muslim Arabs began a conquest of the Iranian plateau and conquered the Sassanid Empire of the Persians and seized much of the Byzantine Empire populated by the Kurds and others. Ultimately, the various Iranian peoples were converted to Islam including the Persians, Kurds, and Pashtuns. The Iranian peoples would later split along sectarian lines as the Persians (and later the Hazara) adopted the Shia sect, while the majority of other Iranian peoples remained adherents of Sunni Islam. As ancient tribes and identities changed, so did the Iranian peoples, many of whom assimilated foreign cultures and peoples over the centuries.

Later, during the 2nd millennium CE, the Iranian peoples would play prominent roles during the age of Islamic expansion and empire. Noted adversary of the Crusaders, Saladin was an ethnic Kurd, while various empires centered in Iran (including the Safavids) re-established a modern dialect of Persian as the official language spoken throughout much of what is today modern Iran and adjacent parts of Central Asia. Iranian influence spread to the Ottoman Empire where Persian was often spoken at court as well as in the Mughal Empire which began in Afghanistan and shifted to India. All of the major Iranian peoples reasserted their use of Iranian languages following the decline of Arab rule, but would not begin to form modern national identities until the 19th and early 20th centuries (just as Germans and Italians were beginning to formulate national identities of their own).

Geographic distribution

There are an estimated 150 million native speakers of Iranian languages. Currently, most of these Iranian peoples live in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, western Pakistan, the Kurdish areas (sometimes referred to as Kurdistan) of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria, as well as in parts of Uzbekistan (especially Samarkand and Bukhara), and the Caucasus (Ossetia and Azerbaijan). Smaller groups of Iranian peoples can also be found in western China and India (home to the Parsis).

Religion

See also Historical Shi'a-Sunni relations, Persianism, Bahais, Parsis, Persian Jews, Kurdish Jews, Jews of Afghanistan Speakers of Iranian languages mainly follow Abrahamic religions including Islam, Judaism, and Christianity in addition to the Bahai faith, with an unknown number showing no religious affiliation. Of the Muslim Iranian peoples, the majority are followers of the Sunni sect of Islam, while most Persians and Hazaras are Shia. The Christian community is largely represented by the Russian Orthodox followed by most Ossetes. The historical religion of the Persian Empire was Zoroastrianism which continues to have followers in Iran, Pakistan, and India.

Culture

See Aryan mythology, Norouz, Iranian philosophy, Pashtunwali

The early Iranian peoples may have worshipped various deities found throughout other cultures where Indo-Iranian invaders established themselves. The earliest major religion of the Iranian peoples was Zoroastrianism which spread to nearly all of the Iranian peoples living in the Iranian plateau. It is surmised that the early Proto-Iranians and the later ancient peoples their descendants became mixed with and assimilated local cultures over a long period of time, and thus a caste identity was never needed or created by the Iranians in sharp contrast with the Indo-Aryans. The Iranian cultures that emerged in ancient times and following conquests by Alexander the Great and the Arabs all led to drastic changes in Iranic culture as well.

Various other common traits can be discerned amongst the Iranian peoples. The social event Norouz, for example, is a pan-Iranic celebration that is practiced by nearly all of the Iranian peoples, with the exception of the Ossetes. Its origins are traced to Old Iranian times dating as far back 1000 BCE.

Various Iranian peoples exhibit distinct traits that are unique unto themselves. The Pashtuns adhere to a code of honor and culture known as Pashtunwali which has a similar counterpart amongst the Baloch called Mayar that is more hierarchical.

Ethnic diversity

It is largely through linguistic similarities that the Iranian peoples have been linked as many non-Iranic peoples have adopted Iranian languages, notably the Hazara who are believed to be of Mongol origin and the Brahui who are often bilingual in Baluchi and are believed to be partial descendants of some early Dravidian peoples largely found in India. Other common traits have also been identified and a stream of common historical events have often linked the southern Iranian peoples including Hellenistic conquests, the various empires based in Persia, Arab Caliphates, and Turkic invasions.

Although most of the Iranian peoples settled in the Iranian plateau region, many expanded into the periphery, ranging from the Caucasus and Turkey to the Indus and western China. The Iranian peoples have often mingled with other populations with the notable example being the Hazaras who display a distinct Turkic-Mongol background that contrasts with most other Iranian peoples. Similarly, the Baloch have mingled to a small degree with Indian populations such as the Brahui, while the Ossetians have invariably mixed with Georgians and other peoples with whom they live. The Kurds are an example of an eclectic Iranian people who, although displaying some ethnolinguistic ties to other Iranian peoples (in particular their Iranian language and some cultural traits), have substantial genetic ties to the Caucasus and Europe as well as showing some genetic links to Semitic peoples such as Jews and Palestinians.

Modern Persians themselves are also a heterogenous group of peoples descended from various ancient Iranian and indigenous peoples of the Iranian plateau, including the Elamites. Thus, not unlike the previous example of Germanic peoples involving the English, who are of mixed Germanic and Celtic origin, Iranian is an ethno-linguistic group and the Iranian peoples display varying degrees of common ancestry and/or cultural traits that denote their respective identities.

Ethnic and cultural assimilation

In matters relating to culture, the various Turkic-speaking minorities of Iran (notably the Azerbaijani people) and Afghanistan (Uzbeks and Turkmen) are often conversant in Iranian languages, in addition to their own Turkic languages, and have assimilated Iranian culture to the extent that the term Turko-Iranian can be applied. The usage applies to various circumstances that involve historic interaction, intermarriage, cultural assimilation, bilingualism, and cultural overlap or commonalities. Notable amongst this synthesis of Turko-Iranian culture are the Azeris, whose culture, religion, and significant periods of history are linked to the Persians. In fact, throughout much of the expanse of Central Asia and the Middle East, Iranian and Turkic culture has merged in many cases to form various hybrid populations and cultures as evident from various ruling dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs, and Mughals. Iranian cultural influences have also been significant in Central Asia where Turkic invaders are believed to have largely mixed with native Iranian peoples of which only the Tajik remain, in terms of language usage. The areas of the former Soviet Union adjacent to Iran, Afghanistan, and the Kurdish areas (such as Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan) have gone through the prism of decades of Russian and Soviet rule that has reshaped the Turko-Iranian cultures there to some degree.

Genetics

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Genetic testing of Iranian peoples has revealed many common genes for most of the Iranian peoples, but with numerous exceptions and regional variations as to be expected. Some of the common genetic markers may stem from the ancient Proto-Iranians and parallel the spread of Iranian languages which may have also been adopted through a process of assimilation by indigenous peoples and thus account for the diversity found amongst the Iranian peoples. Nonetheless, some preliminary genetic tests suggest a common relationship amongst most of the Iranian peoples:

Populations located west of the Indus basin, including those from Iran, Anatolia and the Caucasus, exhibit a common mtDNA lineage composition, consisting mainly of western Eurasian lineages, with a very limited contribution from South Asia and eastern Eurasia (fig. 1). Indeed, the different Iranian populations show a striking degree of homogeneity. This is revealed not only by the nonsignificant FST values and the PC plot (fig. 6) but also by the SAMOVA results, in which a significant genetic barrier separates populations west of Pakistan from those east and north of the Indus Valley (results not shown). These observations suggest either a common origin of modern Iranian populations and/or extensive levels of gene flow amongst them.

Basically, the findings of this study reveal many common genetic markers found amongst the Iranian peoples from the Tigris to the areas west of the Indus. This correlates with the Iranian languages spoken in the areas that span from the Caucasus to Kurdish areas in the Zagros region and eastwards to western Pakistan and Tajikistan and parts of Uzbekistan in Central Asia. The extensive gene flow is perhaps an indication of the spread of Iranian-speaking peoples whose languages are now spoken mainly upon the Iranian plateau and adjacent regions. These results relate the relationships of Iranian peoples with each other, while other comparative testing reveals some varied origins for Iranian peoples such as the Kurds, who show genetic ties to the Caucasus at considerably higher levels than any other Iranian peoples except the Ossetians as well as links to Semitic populations that live in close proximity such as Jews and Arabs. An inclusive new study that combined all of the previous studies regarding comparative tests showing the relationship of the Kurds with Georgians, Europeans, and Jews was incorporated into a 2005 study that conducted further comparative tests amongst Kurdish groups from various regions. This study entitled 'MtDNA and Y-chromosome Variation in Kurdish Groups' concluded the following:

Kurdish languages belong to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. What is the genetic relationship between Indo-European speaking Kurdish groups and other West Asian Indo-European and non-Indo-European speaking groups? For both mtDNA and the Y-chromosome, all Kurdish groups are more similar to West Asians than to Central Asian, Caucasian, or European groups, and these differences are significant in most cases. However, for mtDNA, Kurdish groups are all most similar to European groups (after West Asians), whereas for the Y-chromosome Kurds are more similar to Caucasians and Central Asians (after West Asians) than to Europeans. Richards et al. (2000) suggested that some Near Eastern mtDNA haplotypes, among them Kurdish ones from east Turkey, presumably originated in Europe and were associated with back-migrations from Europe to the Near East, which may explain the close relationship of Kurdish and European groups with respect to mtDNA. Subsequent migrations involving the Caucasus and Central Asia, that were largely male-mediated, could explain the closer relationship of Kurdish Y-chromosomes to Caucasian/Central Asian Ychromosomes than to European Y-chromosomes. In another study, Kurdish Jews were found to be close to some Muslim Kurds, but so were Ashkenazim and Sephardim, suggesting that much if not most of the genetic similarity between Jewish and Muslim Kurds is from ancient times.

Ultimately, genetic tests reveal that while the Iranian peoples show numerous common genetic markers overall, there are also indications of interaction with other groups and regional variations and genetic drift. In addition, indigenous populations may have survived the waves of early Aryan invasions as cultural assimilation led to large-scale language replacement (as with some Kurds). Further testing will ultimately be required and may further elucidate the relationship of the Iranian peoples with each other and various neighboring populations.

List of Iranian peoples

Speakers of Iranian languages in modern times include:

- Persians

- Tajiks

- Tats

- Pashtuns

- Kurds

- Baloch

- Gilanis

- Mazandaranis

- Bakhtiaris

- Lurs

- Laks

- Talyshi

- Zaza

- Ossetians

- Hazara

See also

External links

- Banuazizi, Ali and Weiner, Myron (eds.). The State, Religion, and Ethnic Politics: Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (Contemporary Issues in the Middle East), Syracuse University Press (August, 1988)

- Khoury, Philip and Kostiner, Joseph. Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East, University of California Press (May, 1991)

- McDowall, David. A Modern History of the Kurds, I.B. Tauris; 3rd Rev edition (May 14, 2004)

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas. Indo-Iranian Languages and Peoples, British Academy (March 27, 2003)

- The Iranian Peoples of the Caucasus, Routledge Curzon

- Ethnologue report for Iranian

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Iranian languages

- The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies: Iranian languages and lierature

- The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies-Articles on: Anthropology, Genealogy & Folklores of the Iranian peoples

- Where West Meets East: The Complex mtDNA Landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian Corridor, Am. J. Hum. Genet., 74:827-845, 2004

- "THE ORIGIN OF THE PRE-IMPERIAL IRANIAN PEOPLES", by Oric Barirov