This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Omnipaedista (talk | contribs) at 15:33, 23 September 2012 (edited formatting). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:33, 23 September 2012 by Omnipaedista (talk | contribs) (edited formatting)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about a group of Turkic peoples. For other uses, see Oghuz.| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (September 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Turkmen also known as Oguzes (a linguistic term designating the Western Turkic or Oghuz languages from the Oghur languages) were a historical Turkic tribal confederation conventionally named Oghuz Yabgu State in Central Asia during the early medieval period. The name Oguz is a Common Turkic word for "tribe". The Oguz confederation migrated westard from the Jeti-su area after a conflict with Karluk branch of Uigurs. The founders of the Ottoman Empire were descendants of the Oguz Yabgu State.

In the 9th century, the Oguzes from the Aral steppes drove Bechens from the Emba and Ural River region toward the west. In the 10th century they inhabited the steppe of the rivers Sari-su, Turgai, and Emba to the north of Lake Balkhash of modern day Kazakhstan. A clan of this nation, the Seljuks, embraced Islam and in the 11th century entered Persia, where they founded the Great Seljuk Empire. Similarly, in the 11th century a Tengriist Oghuz clan—referred to as Uzes or Torks in the Russian chronicles—overthrew Pecheneg supremacy in the Russian steppe. Harried by another Turkic horde, the Kipchaks—a branch of the Kimaks of the middle Irtysh or of the Ob—these Oghuz penetrated as far as the lower Danube, crossed it and invaded the Balkans, where they were either crushed or struck down by an outbreak of plague, causing the survivors either to flee or to join the Byzantine imperial forces as mercenaries (1065).

The Oghuz seem to have been related to the Pechenegs, some of whom were clean-shaven and others of whom had small 'goatee' beards. According to the book Attila and the Nomad Hordes, "Like the Kimaks they set up many carved wooden funerary statues surrounded by simple stone balbal monoliths." The authors of the book go on to note that "Those Uzes or Torks who settled along the Russian frontier were gradually Slavicized though they also played a leading role as cavalry in twelfth and early thirteenth century Russian armies where they were known as Black Hats.... Oghuz warriors served in almost all Islamic armies of the Middle East from the eleventh century onwards, in Byzantium from the ninth century, and even in Spain and Morocco." In later centuries, they adapted and applied their own traditions and institutions to the ends of the Islamic world and emerged as empire-builders with a constructive sense of statecraft.

Linguistically, the Oghuz are listed together with the old Kimaks of the middle Yenisei of the Ob, the old Kipchaks who later emigrated to southern Russia, and the modern Kirghiz in one particular Turkic group, distinguished from the rest by the mutation of the initial y sound to j (dj).

"The term 'Oghuz' was gradually supplanted among the Turks themselves by Türkmen, 'Turcoman', from the mid tenth century on, a process which was completed by the beginning of the thirteenth."

"The Ottoman dynasty, who gradually took over Anatolia after the fall of the Seljuks, toward the end of the thirteenth century, led an army that was also predominantly Oghuz."

Origins

Main article: Origin of the Turks"In 178-177 BC, the Xiongnu shan-yü Mao-tun subdued a people called Hu-chieh, west of Wu-sun. The early pronunciation of this transliteration suggests that they were ancestors of Oghur/Oghuz." They were certainly related to the Chinese tribes of the east.

The original homeland of the Oghuz, like other Turks, was the Ural-Altay region of Central Asia, which has been the domain of Turkic peoples since antiquity. Although their mass-migrations from Central Asia occurred from the 9th century onwards, they were present in areas west of the Caspian Sea centuries prior, although smaller in numbers and perhaps living with other Turks. For example, the Book of Dede Korkut, the historical epic of the Oghuz Turks, was written from the ninth and tenth centuries.

According to many historians, the usage of the word "Oghuz" is dated back to the advent of the Huns (220 BC). The title of "Oghuz" (Oguz Khan) was given to Mau-Tun, the founder of the Hun Empire, which is often considered the first Turkic political entity in Central Asia.

Also in the 2nd century BC, a Turkic tribe called O-kut or Wuqi 呼揭, 呼得, 乌揭, 乌护 who were described as a western enemy of the Huns (referred to in Chinese sources, Shiji, 110 and Suishu, 84) were mentioned in the area of the Irtysh River, in present-day Lake Zaysan. The Greek sources used the name Oufi (or Ouvvi) to describe the Oghuz Turks, a name they had also used to describe the Huns centuries earlier.

A number of tribal groupings bearing the name Oghuz, often with a numeral representing the number of united tribes in the union, are noted.

The mention of the "six Oghuz tribal union" in the Turkic Orhun inscriptions (6th century) pertains to the unification of the six Turkic tribes which became known as the Oghuz. This was the first written reference to Oghuz, and was dated to the period of the Göktürk empire. The Oghuz community gradually grew larger, uniting more Turkic tribes prior and during the Göktürk establishment.

Prior to the Göktürk state, there are references to the Sekiz-Oghuz ("eight-Oghuz") and the Dokuz-Oghuz ("nine-Oghuz") union. The Oghuz Turks under Sekiz-Oghuz and the Dokuz-Oghuz state formations ruled different areas in the vicinity of the Altay mountains. During the establishment of the Göktürk state, Oghuz tribes inhabited the Altay mountain region and also lived in northeastern areas of the Altay mountains along the Tula River. They were also present as a community near the Barlik River in present-day northern Mongolia.

Their main homeland and domain in the ensuing centuries was the area of Transoxiana, in western Turkestan.

This land became known as the "Oghuz steppe," which is an area between the Caspian and Aral Seas. Ibn al-Athir, an Arab historian, declared that the Oghuz Turks had come to Transoxiana in the period of the caliph Al-Mahdi in the years between 775 and 785. In the period of the Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun (813–833), the name Oghuz starts to appear in the works of Islamic writers. By 780, the eastern parts of the Syr Darya were ruled by the Karluk Turks and the western region (Oghuz steppe) was ruled by the Oghuz Turks.

Turkic history

According to other records, Togarmah is regarded as the ancestor of the Turkic peoples. For example, The French Benedictine monk and scholar Calmet (1672–1757) places Togarmah in Scythia and Turcomania (in the Eurasian Steppes and Central Asia). Also in his letters, King Joseph ben Aaron, the ruler of the Khazars, writes:

- "You ask us also in your epistle: "Of what people, of what family, and of what tribe are you?" Know that we are descended from Noach's son Japhet, through his son Gomer through his son Togarmah. I have found in the genealogical books of my ancestors that Togarmah had ten sons. These are their names:

- the eldest was Ujur (Agiôr - Uyghur),

- the second Tauris (Tirôsz - Tauri),

- the third Avar (Avôr - Avar),

- the fourth Uauz (Ugin - Oghuz),

- the fifth Bizal (Bizel - Pecheneg),

- the sixth Tarna,

- the seventh Khazar (Khazar),

- the eighth Janur (Zagur),

- the ninth Bulgar (Balgôr - Bulgar),

- the tenth Sawir (Szavvir/Szabir - Sabir)."

In Jewish sources too Togarmah is listed as the father of the Turkic peoples: The medieval Jewish scholar: Joseph ben Gorion lists in his Josippon the ten sons of Togarma as follows:

- Kozar (the Khazars)

- Pacinak (the Pechenegs)

- Aliqanosz (the Alans)

- Bulgar (the Bulgars)

- Ragbiga (Ragbina, Ranbona)

- Turqi (possibly the Kökturks)

- Buz (the Oghuz)

- Zabuk

- Ungari (either the Hungarians or the Oghurs/Onogurs)

- Tilmac (Tilmic/Tirôsz - Tauri)."

In the Chronicles of Jerahmeel, they are listed as:

- Cuzar (the Khazars)

- Pasinaq (the Pechenegs)

- Alan (the Alans)

- Bulgar (the Bulgars)

- Kanbinah

- Turq (possibly the Kökturks)

- Buz (the Oghuz)

- Zakhukh

- Ugar (either the Hungarians or the Oghurs/Onogurs)

- Tulmes (Tirôsz - Tauri)

Another medieval rabbinic work, the Book of Jasher, further corrupts these same names into:

- Buzar (the Khazars)

- Parzunac (the Pechenegs)

- Balgar (the Bulgars)

- Elicanum (the Alans)

- Ragbib

- Tarki (the Kökturks)

- Bid (the Oghuz)

- Zebuc

- Ongal (Hungarians or Oghurs/Onogurs)

- Tilmaz (Tirôsz - Tauri).

In Arabic records, Togorma's tribes are these:

- Khazar (the Khazars)

- Badsanag (the Pechenegs)

- Asz-alân (the Alans)

- Bulghar (the Bulgars)

- Zabub

- Fitrakh (Kotrakh?) (Ko-etrakh. Etrakh means turks )

- Nabir

- Andsar (Ajhar)

- Talmisz (Tirôsz - Tauri)

- Adzîgher (Adzhigardak?).

The Arabic account however, also adds an 11th clan: Anszuh.

Yet another tradition of the sons of Togarmah appears in Pseudo-Philo, where their names are said to be "Abiud, Saphath, Asapli, and Zepthir". The Chronicles of Jerahmeel, in addition to giving the above names from Yosippon, elsewhere lists Togarmah's sons similarly as "Abihud, Shafat, and Yaftir".

Social units

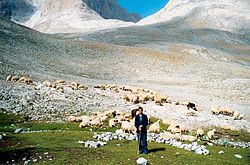

The militarism that the Oghuz empires were very well known for was rooted in their centuries-long nomadic lifestyle. In general they were a herding society which possessed certain military advantages that sedentary societies did not have, particularly mobility. Alliances by marriage and kinship, and systems of "social distance" based on family relationships were the connective tissues of their society.

In Oghuz traditions, "society was simply the result of the growth of individual families". But such a society also grew by alliances and the expansion of different groups, normally through marriages. The shelter of the Oghuz tribes was a tent-like dwelling, erected on wooden poles and covered with skin, felt, or hand-woven textiles, which is called a yurt.

Their cuisine included yahni (stew), kebabs, Toyga çorbası (lit. "wedding soup;" a soup made from wheat flour and yogurt), Kımız (a traditional drink of the Turks, made from fermented horse milk), Pekmez (a syrup made of boiled grape juice) and helva made with wheat starch or rice flour, tutmac (noodle soup), yufka (flattened bread), katmer (layered pastry), chorek (ring-shaped buns), bread, clotted cream, cheese, milk and ayran (diluted yogurt beverage), as well as wine.

Social order was maintained by emphasizing "correctness in conduct as well as ritual and ceremony." Ceremonies brought together the scattered members of the society to celebrate birth, puberty, marriage, and death. Such ceremonies had the effect of minimizing social dangers and also of adjusting persons to each other under controlled emotional conditions.

Patrilineally related men and their families were regarded as a group with rights over a particular territory and were distinguished from neighbours on a territorial basis. Marriages were often arranged among territorial groups so that neighbouring groups could become related, but this was the only organizing principle that extended territorial unity. Each community of the Oghuz Turks was thought of as part of a larger society composed of distant as well as close relatives. This signified "tribal allegiance." Wealth and materialistic objects were not commonly emphasized in Oghuz society and most remained herders, and when settled they would be active in agriculture.

Status within the family was based on age, gender, relationships by blood, or marriageability. Males as well as females were active in society, yet men were the backbones of leadership and organization. According to the Book of Dede Korkut which demonstrates the culture of the Oghuz Turks, women were "expert horse riders, archers, and athletes." The elders were respected as repositories of both "secular and spiritual wisdom."

Homeland in Transoxiana

In the 8th century, the Oghuz Turks made a new home and domain for themselves in the area between the Caspian and Aral seas, a region that is often referred to as Transoxiana, the western portion of Turkestan. They had moved westward from the Altay mountains passing through the Siberian steppes and settled in this region, and also penetrated into southern Russia and the Volga from their bases in west China.

In his accredited work titled Diwan Lughat al-Turk, Mahmud of Kashgar, a Turkic scholar of the 11th century, described the Karachuk Mountains which are located just east of the Aral Sea as the original homeland of the Oghuz Turks. The Karachuk mountains are now known as the Tengri Tagh (Tian Shan in Chinese) Mountains, and they are adjacent to Syr Darya.

The extension from the Karachuk Mountains towards the Caspian Sea (Transoxiana) was called the "Oghuz Steppe Lands" from where the Oghuz Turks established trading, religious and cultural contacts with the Abbasid Arab caliphate who ruled to the south. This is around the same time that they first converted to Islam and renounced their Tengriism belief system. The Arab historians mentioned that the Oghuz Turks in their domain in Transoxiana were ruled by a number of kings and chieftains.

It was in this area that they later founded the Seljuk Empire, and it was from this area that they spread west into western Asia and eastern Europe during Turkic migrations from the 9th until the 12th century. The founders of the Ottoman Empire were also Oghuz Turks.

Oghuz and Yörüks

Main article: Yörüks

The Yörük, also Yürüks or Yuruks are a Turkic people ultimately of Oghuz descent, some of whom are still semi-nomadic, primarily inhabiting the mountains of Anatolia and partly Balkan peninsula. Their name derives from the Old-Turkic verb from Eastern Turkish dialect (Çagatay dialekt)- yörü "yörümek", but Western Turkish dialect (Garbi Türkçe) yürü- (yürümek in infinitive), which means "to walk", with the word Yörük or Yürük designating "those who walk, walkers".

The Yörük to this day appear as a distinct segment of the population of Macedonia and Thrace where they settled as early as the 14th century. While today the Yörük are increasingly settled, many of them still maintain their nomadic lifestyle, breeding goats and sheep in the Taurus Mountains and further eastern parts of mediterranean regions (in southern Anatolia), in the Pindus (Epirus, Greece and southern Albania), the Šar Mountains (Republic of Macedonia), the Pirin and Rhodope Mountains (Bulgaria) and Dobrudja. An earlier offshoot of the Yörüks, the Kailars or Kayılar Turks were amongst the first Turkish colonists in Europe, (Kailar or Kayılar being the Turkish name for the Greek town of Ptolemaida which took its current name in 1928) formerly inhabiting parts of the Greek regions of Thessaly and Macedonia. Settled Yörüks could be found until 1923, especially near and in the town of Kozani. The Yörüks are credited with the conversion to Islam in the 18th century, after a period of cohabitation, of a part of the native Meglen Vlachs of Greece who in 1923 were expelled to Turkey under the terms of the population exchange between the two countries.

Oghuz Turk dynasties

Traditional tribal organization

Bozoklar (Brown Arrows)

- Kayı (founders of the Ottoman dynasty and Ghaznavids Dynasty and Jandarids)

- Bayat (founders of the Qajar dynasty and Dulkadirids Fuzûlî )

- Alkaevli

- Karaevli

- Yazır

- Döger (founders of the Artuqid dynasty)

- Dodurga

- Yaparlı

- Afshar(founders of the Afsharid dynasty Nader Shah and Karamanid dynasty )

- Kızık

- Begdili (founders of the Khwarazmian dynasty )

- Kargın

Üçoklar (Three Arrows)

- Bayandur (founders of the Ak Koyunlu dynasty and Safavid dynasty )

- Pecheneg

- Çavuldur Tzachas

- Chepni

- Salur (founders of the Kara Koyunlu dynasty and Kadi Burhan al-Din and Salgurlular State in Iraq Salar people )

- Eymür Karakalpaks

- Alayuntlu

- Yüreğir (founders of the Ramadanid dynasty)

- İgdir

- Büğdüz

- Yıva

- Kınık (founders of the Seljuk Empire

Turcoman and Turkmen

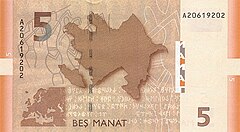

The terms "Turkmen" and "Turcoman" were often used as a designation for the Muslim-Oghuz Turks (Azerbaijanis, Turks of Turkey, Central Asian Turks) in periods of history although other Turkic factions described as Turks (Kumans, Khazars, Uyghurs, etc.), and the ethnic name that the modern Turkmens of Central Asia use to designate their nationality was formed later.

Although a term most commonly used for the Oghuz of Central Asia, the name "Turkmen" or "Turcoman" once applied to Azerbaijanis and the Turks of Turkey as well, distinguishing between other Turks and non-Muslim Turks. Some western books which were written prior to the modern age use the terms "Turcoman" for the descendants of the Oghuz Turks who were not from the Turkmen nationality of Central Asia, which is one of the branches of the Oghuz.

For example, many sources prior to the modern age claim that the largest component of the population of Azerbaijan is composed of "Turcoman tribes." The "Turkmen" reference in history books which is often used for Azerbaijanis and Turks of Turkey simply means "Muslim Turk" or "Muslim western Turk," which means Oghuz Turk.

In Turkey the word "Turkmen" refers to nomadic Turkish tribes (all Muslims), some of whom still continue this lifestyle.

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica the name Turkmen is a synonym of Oghuz, which includes all the Turkish (Turkic) population who live to the southwest of Central Asia:

in other countries:

- Afghanistan

- Pakistan

- Iraq, Syria and other Arab countries

- Greece, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Serbia, Moldova and the Republic of Macedonia

Turkish historian Yılmaz Öztuna presents almost the same definition of the name "Turkmen." He labels the Turkmen Oghuz or western Turkish populations as:

- Ottomans

- Azerbaijan

- Turkmen (Turkmenistan)

Literature

Oghuz Turkish literature includes the famous Book of Dede Korkut which was UNESCO's 2000 literacy work of the year, as well as the Oguznama and Köroğlu epics which are part of the literary history of Azerbaijanis, Turks of Turkey and Turkmens. The modern and classical literature of Azerbaijan, Turkey and Central Asia are also considered Oghuz literature, since it was produced by their descendants.

The Book of Dede Korkut is an invaluable collection of epics and stories, bearing witness to the language, the way of life, religions, traditions and social norms of the Oghuz Turks in Azerbaijan, Turkey and Central Asia.

See also

- Afshar dynasty

- Gokturks

- Kimek

- Oghuz languages

- Salar people

- Tokuz-Oguzes

- Oghuz Khan

- Mythology of the Turkic and Mongolian peoples

- Timeline of Turks (500-1300)

Notes

- Grousset, R. The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press, 1991, p. 148.

- Grousset, R. The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press, 1991, p. 186.

- Hupchick, D. The Balkans. Palgrave, 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Nicolle, David (1990). Attila and the Nomad Hordes. Osprey Publishing. pp. 46–47. ISBN 0-85045-996-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lewis, G. The Book of Dede Korkut. Penguin Books, 1974, p. 10.

- Lewis, p. 9.

- Torday, L., Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. The Durham Academic Press, 1997, pp. 220-221.

- Alstadt, Audrey. The Azerbaijani Turks, p.11. Hoover Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8179-9182-4

- Bichurin N.Ya., "Collection of information on peoples in Central Asia in ancient times", vol. 1, Sankt Petersburg, 1851, pp. 56-57

- Taskin V.S., "Materials on history of Sünnu", transl., 1968, Vol. 1, p. 129

- Oguz entry, Encyclopaedia Britannica Online.

- The Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. (1835) B. B. Edwards and J. Newton Brown. Brattleboro, Vermont, Fessenden & Co., p. 1125.

- Pritsak O. & Golb. N: Khazarian Hebrew Documents of the Tenth Century, Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1982.

- N. K. Singh, A. M. Khan, Encyclopaedia of the world muslims: Tribes, Castes and Communities, Vol.4, Delhi 2001, p.1542

- Grolier Incorporated, Academic American encyclopedia, vol.20, 1989, p.34

- Sir Gerard Clauson, An etymological dictionary of pre-thirteenth-century Turkish, Oxford 1972, p.972

- Turkish Language Association - TDK Online Dictionary. Yorouk, yorouk Template:Tr icon

- "yuruk." Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. Merriam-Webster. 2002.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition - Macedonia: Races

- Ptolemaida.net - History of Ptolemaida web page

- "Some Ottoman genealogies claim, perhaps fancifully, descent from Kayı.", Carter Vaughn Findley, The Turks in World History, pp. 50, 2005, Oxford University Press

- Oğuzlar, Oğuz Türkleri

- Kafesoğlu, İbrahim. Türk Milli Kültürü. Türk Kültürünü Araştırma Enstitüsü, 1977. page 134

References

- Grousset, R., The Empire of the Steppes, 1991, Rutgers University Press

- Nicole, D., Attila and the Huns, 1990, Osprey Publishing

- Lewis, G., The Book of Dede Korkut, "Introduction", 1974, Penguin Books

- Minahan, James B. One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Press, 2000. page 692

- Aydın, Mehmet. Bayat-Bayat boyu ve Oğuzların tarihi. Hatiboğlu Yayınevi, 1984. web page

External links

- The Book of Dede Korkut (pdf format) at the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative

- Similarities between the epics of Dede Korkut and Alpamysh

- A page dedicated to Oguz Khan

- The Old Turkic Inscriptions.