This is an old revision of this page, as edited by BilCat (talk | contribs) at 16:12, 24 March 2013 (Reverted edits by 70.83.160.23 (talk) to last version by Andy Dingley). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:12, 24 March 2013 by BilCat (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 70.83.160.23 (talk) to last version by Andy Dingley)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| Part of a series on |

| Aircraft propulsion |

|---|

|

Shaft engines: driving propellers, rotors, ducted fans or propfans |

| Reaction engines |

An aircraft engine is the component of the propulsion system for an aircraft that generates mechanical power. Aircraft engines are almost always either lightweight piston engines or gas turbines.

Timeline of aircraft engine development

- 1848: John Stringfellow made a steam engine capable of powering a model, albeit with negligible payload.

- 1903: Charlie Taylor built an inline aeroengine for the Wright Flyer (12 horsepower).

- 1903: Manly-Balzer engine sets standards for later radial engines.

- 1906: Léon Levavasseur produces a successful water-cooled V8 engine for aircraft use.

- 1908: René Lorin patents a design for the ramjet engine.

- 1908: Gnome Omega designed, the world's first rotary engine to be produced in quantity. In 1909 a Gnome powered Farman III aircraft won the prize for the greatest non-stop distance flown at the Reims Grande Semaine d'Aviation setting a world record for endurance of 180 kilometres (110 mi).

- 1910: Coandă-1910, an unsuccessful ducted fan aircraft exhibited at Paris Aero Salon, powered by a piston engine. The aircraft never flew, but a patent was filed for routing exhaust gases into the duct to augment thrust.

- 1914: Auguste Rateau suggests using exhaust-powered compressor – a turbocharger – to improve high-altitude performance; not accepted after the tests

- 1917-18 - The Idflieg-numbered R.30/16 example of the Imperial German Luftstreitkräfte's Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI heavy bomber becomes the earliest known supercharger-equipped aircraft to fly, with a Mercedes D.II straight-six engine placed in the central fuselage to power a Brown-Boveri mechanical supercharger for the R.30/16's quartet of Mercedes D.IVa powerplants.

- 1918: Sanford Alexander Moss picks Rateau's idea and creates the first successful turbocharger

- 1926: Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar IV (S), the first series-produced supercharged engine for aircraft use; two-row radial with a gear-driven centrifugal supercharger.

- 1930: Frank Whittle submitted his first patent for turbojet engine.

- June 1939: Heinkel He 176 is the first successful aircraft to fly powered solely by a liquid-fueled rocket engine.

- August 1939: Heinkel HeS 3 turbojet propels the pioneering German Heinkel He 178 aircraft.

- 1940: Jendrassik Cs-1, the world's first run of the turboprop engine. It is not put into service.

- 1944: Messerschmitt Me 163B Komet, the world's first rocket propelled combat aircraft deployed.

- 1945: First turboprop powered aircraft flies, a Gloster Meteor with two Rolls-Royce Trent

- 1947: Bell X-1 rocket propelled aircraft exceeds the speed of sound.

- 1948: 100 shp 782, the first turboshaft engine to be aplied to aircraft use; in 1950 used to develop the larger 280 shp (210 kW) Turbomeca Artouste.

- 1949: Leduc 010, the world's first ramjet-powered aircraft flight.

- 1950: Rolls-Royce Conway, the world's first production turbofan, enters service.

- 1960s: TF39 high bypass turbofan enters service delivering greater thrust and much better efficiency.

- 2002: HyShot scramjet flew in dive.

- 2004: Hyper-X, the first scramjet to maintain altitude.

Shaft engines

Reciprocating (piston) engines

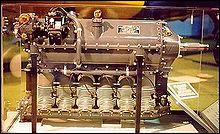

Main article: reciprocating engineIn-line engine

Main article: Straight engineThis type of engine has cylinders lined up in one row. It typically has an even number of cylinders, but there are instances of three- and five- cylinder engines. The biggest advantage of an inline engine is that it allows the aircraft to be designed with a narrow frontal area for low drag. If the engine crankshaft is located above the cylinders, it is called an inverted inline engine, which allows the propeller to be mounted up high for ground clearance even with short landing gear. The disadvantages of an inline engine include a poor power-to-weight ratio, because the crankcase and crankshaft are long and thus heavy. An in-line engine may be either air-cooled or liquid-cooled, but liquid-cooling is more common because it is difficult to get enough air-flow to cool the rear cylinders directly. Inline engines were common in early aircraft, including the Wright Flyer, the aircraft that made the first controlled powered flight. However, the inherent disadvantages of the design soon became apparent, and the inline design was abandoned, becoming a rarity in modern aviation.

V-type engine

Cylinders in this engine are arranged in two in-line banks, typically tilted 60-90 degrees apart from each other and driving a common crankshaft. The vast majority of V engines are water-cooled. The V design provides a higher power-to-weight ratio than an inline engine, while still providing a small frontal area. Perhaps the most famous example of this design is the legendary Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, a 27-litre (1649 in) 60° V12 engine used in, among others, the Spitfires that played a major role in the Battle of Britain.

Horizontally opposed engine

Main article: Flat engine

An horizontally opposed engine, also called a flat or boxer engine, has two banks of cylinders on opposite sides of a centrally located crankcase. The engine is either air-cooled or liquid-cooled, but air-cooled versions predominate. Opposed engines are mounted with the crankshaft horizontal in airplanes, but may be mounted with the crankshaft vertical in helicopters. Due to the cylinder layout, reciprocating forces tend to cancel, resulting in a smooth running engine. Unlike a radial engine, an opposed engine does not experience any problems with hydrostatic lock.

Opposed, air-cooled four- and six-cylinder piston engines are by far the most common engines used in small general aviation aircraft requiring up to 400 horsepower (300 kW) per engine. Aircraft that require more than 400 horsepower (300 kW) per engine tend to be powered by turbine engines.

H configuration engine

Main article: H engineAn H configuration engine is essentially a pair of horizontally opposed engines placed together, with the two crankshafts geared together.

Radial engine

This type of engine has one or more rows of cylinders arranged around a centrally located crankcase. Each row generally has an odd number of cylinders to produce smooth operation. A radial engine has only one crank throw per row and a relatively small crankcase, resulting in a favorable power-to-weight ratio. Because the cylinder arrangement exposes a large amount of the engine's heat-radiating surfaces to the air and tends to cancel reciprocating forces, radials tend to cool evenly and run smoothly. The lower cylinders, which are under the crankcase, may collect oil when the engine has been stopped for an extended period. If this oil is not cleared from the cylinders prior to starting the engine, serious damage due to hydrostatic lock may occur.

Most radial engines have the cylinders arranged evenly around the crankshaft, although some early engines, sometimes called semi-radials or fan configuration engines, had an uneven arrangement. The best known engine of this type is the Anzani engine, which was fitted to the Bleriot XI used for the first flight across the English Channel in 1909. This arrangement had the drawback of needing a heavy counterbalance for the crankshaft, but was used to avoid the spark plugs oiling up.

In military aircraft designs, the large frontal area of the engine acted as an extra layer of armor for the pilot. Also air-cooled engines, without vulnerable radiators, are slightly less prone to battle damage, and on occasion would continue running even with one or more cylinders shot away. However, the large frontal area also resulted in an aircraft with an aerodynamically inefficient increased frontal area.

Rotary engine

Rotary engines have the cylinders in a circle around the crankcase, as in a radial engine, (see below), but the crankshaft is fixed to the airframe and the propeller is fixed to the engine case, so that the crankcase and cylinders rotate. The advantage of this arrangement is that a satisfactory flow of cooling air is maintained even at low airspeeds, retaining the weight advantage and simplicity of a conventional air-cooled engine without one of their major drawbacks. The first practical rotary engine was the Gnome Omega designed by the Seguin brothers and first flown in 1909. Its relative reliability and good power to weight ratio changed aviation dramatically. Before the first World War most speed records were gained using Gnome-engined aircraft, and in the early years of the war rotary engines were dominant in aircraft types for which speed and agility were paramount. To increase power engines with two rows of cylinder were built.

However, the gyroscopic effects of the heavy rotating engine produced handling problems in aircraft and the engines also consumed large amounts of oil, since they used total loss lubrication, oil being mixed with the fuel and ejected with the exhaust gases. Castor oil was used for lubrication, since it is not soluble in petrol: the resultant fumes were nauseating to the pilots. Engine designers had always been aware of the many limitations of the rotary engine. When the static style engines became more reliable, gave better specific weights and fuel consumption, the days of the rotary engine were numbered.

Turbine-powered

Turboprop

While military fighters require very high speeds, many civil airplanes do not. Yet, civil aircraft designers wanted to benefit from the high power and low maintenance that a gas turbine engine offered. Thus was born the idea to mate a turbine engine to a traditional propeller. Because gas turbines optimally spin at high speed, a turboprop features a gearbox to lower the speed of the shaft so that the propeller tips don't reach supersonic speeds. Often the turbines that drive the propeller are separate from the rest of the rotating components so that they can rotate at their own best speed (referred to as a free-turbine engine). A turboprop is very efficient when operated within the realm of cruise speeds it was designed for, which is typically 200 to 400 mph (320 to 640 km/h).

Turboshaft

Turboshaft engines are used primarily for helicopters and auxiliary power units. A turboshaft engine is very similar to a turboprop, with a key difference: In a turboprop the propeller is supported by the engine, and the engine is bolted to the airframe. In a turboshaft, the engine does not provide any direct physical support to the helicopter's rotors. The rotor is connected to a transmission, which itself is bolted to the airframe, and the turboshaft engine simply feeds the transmission via a rotating shaft. The distinction is seen by some as a slim one, as in some cases aircraft companies make both turboprop and turboshaft engines based on the same design..

Reaction engines

Main article: Jet engineReaction engines generate the thrust to propel an aircraft by ejecting the exhaust gases at high velocity from the engine, the resultant reaction of forces driving the aircraft forwards. The most common reaction propulsion engines flown are turbojet, turbofan and rocket. Other types such as pulsejets, ramjets, scramjets and Pulse Detonation Engines have also flown. In jet engines the oxygen necessary for fuel combustion comes from the air, while rockets carry oxygen in some form as part of the fuel load, permitting their use in space.

Jets

Turbojet

A turbojet is a type of gas turbine engine that was originally developed for military fighters during World War II. A turbojet is the simplest of all aircraft gas turbines. It features a compressor to draw air in and compress it, a combustion section that adds fuel and ignites it, one or more turbines that extract power from the expanding exhaust gases to drive the compressor, and an exhaust nozzle that accelerates the exhaust out the back of the engine to create thrust. When turbojets were introduced, the top speed of fighter aircraft equipped with them was at least 100 miles per hour faster than competing piston-driven aircraft. The relative simplicity of turbojet designs lent them to wartime production. In the years after the war, the drawbacks of the turbojet gradually became apparent. Below about Mach 2, turbojets are very fuel inefficient and create tremendous amounts of noise. Early designs also respond very slowly to power changes, a fact that killed many experienced pilots when they attempted the transition to jets. These drawbacks eventually led to the downfall of the pure turbojet, and only a handful of types are still in production. The last airliner that used turbojets was the Concorde, whose Mach 2 airspeed permitted the engine to be highly efficient.

Turbofan

A turbofan engine is much the same as a turbojet, but with an enlarged fan at the front that provides thrust in much the same way as a ducted propeller, resulting in improved fuel-efficiency. Though the fan creates thrust like a propeller, the surrounding duct frees it from many of the restrictions that limit propeller performance. This operation is a more efficient way to provide thrust than simply using the jet nozzle alone and turbofans are more efficient than propellers in the trans-sonic range of aircraft speeds, and can operate in the supersonic realm. A turbofan typically has extra turbine stages to turn the fan. Turbofans were among the first engines to use multiple spools—concentric shafts that are free to rotate at their own speed—to let the engine react more quickly to changing power requirements. Turbofans are coarsely split into low-bypass and high-bypass categories. Bypass air flows through the fan, but around the jet core, not mixing with fuel and burning. The ratio of this air to the amount of air flowing through the engine core is the bypass ratio. Low-bypass engines are preferred for military applications such as fighters due to high thrust-to-weight ratio, while high-bypass engines are preferred for civil use for good fuel efficiency and low noise. High-bypass turbofans are usually most efficient when the aircraft is traveling at 500 to 550 miles per hour (800 to 885 km/h), the cruise speed of most large airliners. Low-bypass turbofans can reach supersonic speeds, though normally only when fitted with afterburners.

Pulse jets

Main article: Pulse jet enginePulse jets are mechanically simple devices that—in a repeating cycle—draw air through a no-return valve at the front of the engine into a combustion chamber and ignited it. The combustion forces the exhaust gases out the back of the engine. It produces power as a series of pulses rather than as a steady output, hence the name. The only application of this type of engine was the German unmanned V1 flying bomb of World War II. Though the same engines were also used experimentally for ersatz fighter aircraft, the extremely loud noise generated by the engines caused mechanical damage to the airframe that was sufficient to make the idea unworkable.

Rocket

A few aircraft have used rocket engines for main thrust or attitude control, notably the Bell X-1 and North American X-15. Rocket engines are not used for most aircraft as the energy and propellant efficiency is very poor except at high speeds, but have been employed for short bursts of speed and takeoff. Rocket engines are very efficient only at very high speeds, although they are useful because they produce very large amounts of thrust and weigh very little.

Newer engine types

Wankel engine

Main article: Wankel engine

Another promising design for aircraft use was the Wankel rotary engine. The Wankel engine is about one half the weight and size of a traditional four-stroke cycle piston engine of equal power output, and much lower in complexity. In an aircraft application, the power-to-weight ratio is very important, making the Wankel engine a good choice. Because the engine is typically constructed with an aluminium housing and a steel rotor, and aluminium expands more than steel when heated, a Wankel engine does not seize when overheated, unlike a piston engine. This is an important safety factor for aeronautical use. Considerable development of these designs started after World War II, but at the time the aircraft industry favored the use of turbine engines. It was believed that turbojet or turboprop engines could power all aircraft, from the largest to smallest designs. The Wankel engine did not find many applications in aircraft, but was used by Mazda in a popular line of sports cars. Recently, the Wankel engine has been developed for use in motor gliders where the small size, light weight, and low vibration are especially important.

Wankel engines are becoming increasingly popular in homebuilt experimental aircraft, due to a number of factors. Most are Mazda 12A and 13B engines, removed from automobiles and converted to aviation use. This is a very cost-effective alternative to certified aircraft engines, providing engines ranging from 100 to 300 horsepower (220 kW) at a fraction of the cost of traditional engines. These conversions first took place in the early 1970s, and with hundreds or even thousands of these engines mounted on aircraft, as of 10 December 2006 the National Transportation Safety Board has only seven reports of incidents involving aircraft with Mazda engines, and none of these is of a failure due to design or manufacturing flaws. During the same time frame, they have reports of several thousand reports of broken crankshafts and connecting rods, failed pistons and incidents caused by other components not found in the Wankel engines. Rotary engine enthusiasts refer to piston aircraft engines as "Reciprosaurs," and point out that their designs are essentially unchanged since the 1930s, with only minor differences in manufacturing processes and variation in engine displacement.

Diesel engine

Main article: Aircraft Diesel engineMost aircraft engines use electrical-ignition engines generally using gasoline as a fuel. Starting in the 1930s attempts were made to produce a compression ignition Diesel engine for aviation use. In general, Diesel engines are more reliable and much better suited to running for long periods of time at medium power settings, which is why they are widely used in, for example, trucks and marine engines. The lightweight alloys of the 1930s were not up to the task of handling the much higher compression ratios of diesel engines, so they generally had poor power-to-weight ratios and were uncommon for that reason, although the Clerget 14F Diesel radial engine (1939) has the same power to weight ratio as a gasoline radial. Improvements in Diesel technology in automobiles (leading to much better power-weight ratios), the Diesel's much better fuel efficiency and the high relative taxation of AVGAS compared to Jet A1 in Europe have all seen a revival of interest in the use of diesels for aircraft. Thielert Aircraft Engines converted Mercedes Diesel automotive engines, certified them for aircraft use, and became an OEM provider to Diamond Aviation for their light twin. Financial problems have plagued Thielert, so Diamond's affiliate — Austro Engine — developed the new AE300 turbodiesel, also based on a Mercedes engine. Competing new Diesel engines may bring fuel efficiency and lead-free emissions to small aircraft, representing the biggest change in light aircraft engines in decades. Wilksch Airmotive build 2-stroke Diesel engine (same power to weight as a gasoline engine) for experimental aircraft: WAM 100 (100 hp), WAM 120 (120 hp) and WAM 160 (160 hp)

Precooled jet engines

Main article: Precooled jet engineFor very high supersonic/low hypersonic flight speeds inserting a cooling system into the air duct of a hydrogen jet engine permits greater fuel injection at high speed and obviates the need for the duct to be made of refractory or actively cooled materials. This greatly improves the thrust/weight ratio of the engine at high speed.

It is thought that this design of engine could permit sufficient performance for antipodal flight at Mach 5, or even permit a single stage to orbit vehicle to be practical.

Electric

About 60 electrically powered aircraft, such as the QinetiQ Zephyr, have been designed since the 1960s. Some are used as military drones. In France in late 2007, a conventional light aircraft powered by an 18 kW electric motor using lithium polymer batteries was flown, covering more than 50 kilometers (31 mi), the first electric airplane to receive a certificate of airworthiness.

Limited experiments with solar electric propulsion have been performed, notably the manned Solar Challenger and Solar Impulse and the unmanned NASA Pathfinder aircraft.

Fuel

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (September 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

All aviation fuel is produced to stringent quality standards to avoid fuel-related engine failures. Aviation standards are much more strict than those for road vehicle fuel because an aircraft engine must meet a strictly defined level of performance under known conditions. These high standards mean that aviation fuel costs much more than fuel used for road vehicles.

Aircraft reciprocating (piston) engines are typically designed to run on aviation gasoline. Avgas has a higher octane rating as compared to automotive gasoline, allowing the use of higher compression ratios, increasing power output and efficiency at higher altitudes. Currently the most common Avgas is 100LL, which refers to the octane rating (100 octane) and the lead content (LL = low lead).

Avgas is blended with tetraethyllead (TEL) to achieve these high octane ratings, a practice no longer permitted with road vehicle gasoline. The shrinking supply of TEL, and the possibility of environmental legislation banning its use, has made a search for replacement fuels for general aviation aircraft a priority for pilot's organizations.

Turbine engines and aircraft Diesel engines burn various grades of jet fuel. Jet fuel is a relatively heavy and less volatile petroleum derivative based on kerosene, but certified to strict aviation standards, with additional additives.

See also

- Air safety

- Aircraft engine position number

- Engine configuration

- Hyper engine

- List of aircraft engines

- Model engine

- United States military aero engine designations

Notes

- The world's first series-produced cars with superchargers came earlier than aircraft. These were Mercedes 6/25/40 hp and Mercedes 10/40/65 hp, both models introduced in 1921 and used Roots superchargers. G.N. Georgano, ed. (1982). The new encyclopedia of motorcars 1885 to the present (3rd ed.). New York: Dutton. p. 415. ISBN 0-525-93254-2.

References

- ^ Ian McNeil, ed. (1990). Encyclopedia of the History of Technology. London: Routledge. pp. 315–21. ISBN 0-203-19211-7.

- Gibbs-Smith, Charles Harvard (1970). Aviation: an historical survey from its origins to the end of World War II. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Gibbs-Smith, Charles Harvard (1960). The Aeroplane: An Historical Survey of Its Origins and Development. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Winter, Frank H. (1980). "Ducted Fan or the World's First Jet Plane? The Coanda claim re-examined". The Aeronautical Journal. 84. Royal Aeronautical Society.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Antoniu, Dan; Cicoș, Geroge; Buiu, Ioan-Vasile; Bartoc, Alexandru; Șutic, Robert. Henri Coandă and his technical work during 1906–1918 (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Anima. ISBN 978-973-7729-61-3.

- Guttman, Jon (2009). SPAD XIII vs. Fokker D VII: Western Front 1918 (1st ed.). Oxford: Osprey. pp. 24–25. ISBN 1-84603-432-9.

- Powell, Hickman (Jun 1941). "He Harnessed a Tornado..." Popular Science.

- Anderson, John D (2002). The airplane: A history of its technology. Reston, VA, USA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. pp. 252–53. ISBN 1-56347-525-1.

- Gibbs-Smith, C.H. (2003). Aviation. London: NMSO. p. 175. ISBN 1 9007 4752 9.

- "ASH 26 E Information". DE: Alexander Schleicher. Archived from the original on 2006-10-08. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- "Diamond Twins Reborn". Flying Mag. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ Worldwide première: first aircraft flight with electrical engine, Association pour la Promotion des Aéronefs à Motorisation Électrique, December 23, 2007.

- Superconducting Turbojet, Physorg.com.

- Voyeur, Litemachines.

- "EAA'S Earl Lawrence Elected Secretary of International Aviation Fuel Committee" (Press release).

External links

- Aircraft Engines and Aircraft Engine Theory (includes links to diagrams)

- The Aircraft Engine Historical Society

- Aircraft Engine Efficiency: Comparison of Counter-rotating and Axial Aircraft LP Turbines

- The History of Aircraft Power Plants Briefly Reviewed : From the " 7 lb. per h.p" Days to the " 1 lb. per h.p" of To-day

- "The Quest for Power" a 1954 Flight article by Bill Gunston

| Aviation lists | |

|---|---|

| General | |

| Military | |

| Accidents / incidents | |

| Records | |