This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 202.6.138.33 (talk) at 12:38, 26 June 2006 (→National governing bodies). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:38, 26 June 2006 by 202.6.138.33 (talk) (→National governing bodies)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the sport, which is distinguished from stage fencing and academic fencing (mensur). For fences and the process of erecting them, see fence. For other uses, see fence (disambiguation).

In the broadest possible sense, fencing is the art and science of armed combat involving cutting, stabbing or bludgeoning weapons directly manipulated by hand, rather than shot or thrown (in other words, swords, knives, pikes, bayonets, batons, clubs, and so on). In contemporary common usage, fencing tends to refer specifically to European schools of swordsmanship and to the modern Olympic sport that has evolved out of them.

History

- See also Historical European Martial Arts

The term fencing derives from the Middle English fense, circa 1330, ultimately deriving from the Latin defendere "ward off, protect," from de- "from, away" + fendere "to strike, push". It was first used in writing as a verb in reference to swordsmanship by Shakespeare, in The Merry Wives of Windsor (1598): "Alas sir, I cannot fence."

Fencing can be traced at least as far back as Ancient Egypt. The earliest known depiction of a fencing bout, complete with practice weapons, safety equipment, and judges, is a relief in a temple near Luxor built by Ramesses III around 1190 BC. The Greeks and Romans had systems of martial arts and military training that included swordsmanship, and fencing-schools and professional champions were known throughout medieval Europe.

The earliest surviving record of Western techniques of fencing is the manuscript known as MS I.33, which was created in southern Germany c. 1300 and today resides at the Royal Armouries in Leeds. Throughout the Middle Ages, masters continued to teach systems for using the sword (together with other weapons and grappling) to noble and non-noble alike.

The wearing of the sword with civilian dress (a custom that had begun in the late fifteenth century on the Iberian Peninsula) gradually gave rise to a new system of civilian swordsmanship based more on the thrust than on the cut, with the aim being to keep the adversary at a distance with the point, and slay him there. This gave rise to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century systems of using the rapier and the seventeenth and eighteenth century smallsword. Though swords ceased to be an article of everyday dress after the French Revolution, they continued to be used in warfare and to resolve disputes of honour in formal duels through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth.

Though antagonistic competition in fencing is as old as the art itself, the modern sport of fencing originated in the first Olympic Games in 1896. The first few years of fencing as a sport were chaotic, with important rule disagreements among schools of fencing from different countries, notably the representatives of the French and Italian schools. This state of affairs ended in 1913, with the foundation of the Fédération Internationale d'Escrime (FIE) in Paris. The stated purpose of the FIE is to codify and regulate the practice of the sport of fencing, particularly for the purpose of international competition. The foundation of the FIE is a convenient breaking point between the classical and the modern traditions of fencing.

Philosophies

There are many autonomous directions in contemporary fencing:

- Sport fencing, also known as Olympic fencing, is the sort of fencing seen in most competitions (including the Olympic Games). It is conducted according to the rules laid down by the FIE (the international governing body), which are roughly based on a set of conventions developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to govern the practice of fencing as a martial art and a gentlemanly accomplishment. Due to technical developments and ideological disagreements, the details are subject to frequent revisions and amendments. This article is predominantly about sport fencing.

- Classical fencing is differentiated from sport fencing as being closer (in various degrees) to swordplay as a martial art. Those who call themselves classical fencers may advocate the modern sport's return to what they see as more authentic practices. In some quarters, this debate has been extremely bitter and has resulted in a virtual schism between the mainstream fencing community and a group of traditionalists who want to reinstate the "classical fencing" of the late 19th and early 20th century.

- Historical fencing is a type of historical martial arts reconstruction based on the surviving texts and traditions. Predictably, historical fencers study an extremely wide array of weapons from different regions and periods. They may work with bucklers, daggers, polearms, bludgeoning weapons etc.

- Academic fencing, or mensur, is a German student tradition. The combat, which uses a type of cutting saber known as the schlager, uses sharpened blades and takes place between members of different fraternities in accordance with a strictly delineated set of conventions, using special protective gear. The ultimate goal is the development of personal character, to show coolness and proper deportment in the face of a sharp blade.

- Stage fencing is a type of fencing that seeks to achieve the maximum theatrical impact. Fights are, generally, choreographed, and fencing actions are often somewhat exaggerated. It is not an exclusive preserve of actors and stuntmen - some people do it as a hobby.

Finally, fencing is often incorporated into recreational roleplay with a historical or a fantasy theme (for example, see The Society for Creative Anachronism or Live-action roleplaying games). Technique and scoring systems vary widely from one group to the next, as do the weapons: depending on the local conventions, participants may use modern sport fencing weapons, period weapons or weapons invented specifically for the purpose (like boffers).

Weapons

Three weapons survive in modern competitive fencing: foil, épée and sabre. The spadroon and the heavy cavalry-style sabre, both of which saw widespread competitive use in the 19th century, fell into disfavour in the early 20th century with the rising popularity of the lighter and faster weapon used today, based on the Italian duelling sabre. Bayonet fencing was somewhat slower to decline with competitions organized by some armed forces as late as the 1940s and 1950s. Today these weapons are the preserve of historical fencing.

While the weapons fencers use differ in size and purpose, their basic construction remains similar across the disciplines. Every weapon has a blade and a hilt. The tip of the blade is generally referred to as the point. The hilt consists of a guard and a grip. The guard (also known as the coquille, or the bellguard) is a metal shell designed to protect the fingers. The grip is the weapon's actual handle. There are a number of commonly used variants (see grip (sport fencing)). The more traditional kind tend to terminate with a pommel, a heavy nut intended to act as a counterwight for the blade.

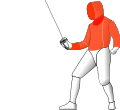

Foil

Main article: Foil (fencing)

The foil is a light and flexible weapon, originally developed in the mid 17th century as a training weapon for the court sword (a light one-handed sword designed almost exclusively for thrusting). It is the weapon that, traditionally, many students practice first. Hits can only be scored by hitting the valid target surface with the point of the weapon. The target area is restricted to the torso. A touch on an off-target area stops the bout but does not score a point. There are "right of way" conventions or priority rules, whose basic idea is that the first person to create a viable threat or the last person to successfully defend receives a "right" to hit. If two hits arrive more or less simultaneously, only the fencer who had the "right of way" receives a point. If priority cannot be assigned unambiguously, no points are awarded. The basic idea behind the foil rules was, originally, to encourage the defence of one's vital areas and to fence in a methodical way with initiative passing back and forth between the two fencers and no last minute counter-attacks which risk a double death.

In modern competitive fencing "electric" weapons are used. These have a push-button on the end, which allows hits to be registered by the electronic scoring apparatus. In order to register, the button must be depressed with a force of at least 4.90 newtons (500 grams-force) for at least 15 milliseconds. Fencers wear conductive (lamé) jackets covering their target area, which allow the scoring apparatus to differentiate between on and off-target hits.

The 1980's saw the widespread use of "flicks" — hits delivered with a whipping motion which bends the blade around the more traditional parries and makes it possible to touch otherwise inaccessible areas, such as the of the back of the opponents. This has been regarded by a substantial number of fencers as an unacceptable departure from the tradition of realistic combat, where only rigid blades would be used. Flicks were not a recent development, however. In 1896, The Lancet published an account of an early "electric scorer" and claimed among its advantages, that "flicks, or blows, or grazes produce no result." Ironically, it is the introduction of electronic scoring to high level competitive foil in the 1950s that is often blamed for the rise in the flick's popularity. In 2004-2005, in an effort to curtail the use of flicks, the FIE raised the contact time required to trigger the scoring apparatus from 1 millisecond to the current 15 milliseconds. This has not made flicks impossible, but it has made them more technically demanding, as glancing hits no longer register, and it is essential that the point arrives more or less square-on. Before they changed the rule, the blade could bend more easily so the back and flanks were easier to hit and score. Now the bend of the blade has lessened.

Épée

Main article: Épée (Fencing)

The épée is the heaviest of the three weapons (approaching the weight of an actual court sword). On low-end weapons, the epee has a relatively stiff blade although new technology has resulted in a flexible blade comparable to the other weapons. The epee is characterized by a V-shaped or approximately traingular cross-section, and a large round guard which offers much more protection to the wrist than the foil guard.

It seems that épée fencing was started at the beginning of the 16th century. After the two-handed broadsword was abandoned and the complete suit of armor was outdated, this new weapon was born in Spain. The rapier épée had a long fine blade with a sharper edge and the tip could be used to cut and thrust. The guard looked like a small basket drilled with holes, having a long, straight ramrod bored through it to be used in engaging and breaking the opponent's blade and point. With the change from heavy broadsword to lighter épée, swordsman were obliged to personalize fencing with trickery and artfulness. Like the foil, the épée is a thrusting weapon: to score a valid hit the fencer must fix the point of his weapon on his opponent's target. However, épée lacks the foil's most artificial conventions: the restricted target area and the priority rules. In épée, a hit can be scored by landing a hit anywhere on the opponent's body. The fencer whose hit lands first receives the point, irrespective of what happened in the preceding phrase. If two hits arrive simultaneously (within 40 milliseconds of each other), a double hit is recorded, and both fencers get a point (except for in modern pentathlon one-hit épée , where both fencers immediately suffer a "double loss").

In order for the scoring apparatus to register a hit, the push-button on the end of the weapon must remain fully depressed for 2-10 milliseconds. To register, the hit must arrive with a force of at least 7.35 newtons (the equivalent of 750 grams of stationary mass) - a slightly higher threshold than the foil's 4.9 newtons (500 grams). All hits register as valid, unless they land on a grounded metal surface, such as a part of the opponent's weapon, in which case they do not register at all. At large events, grounded conductive pistes are often used in order to prevent the registration of hits against the floor. At smaller events and in club fencing, it is generally the responsibility of the referee to watch out for floor hits. These often happen by accident, when an épéeist tries to hit the opponent's foot and misses. In such cases, they are simply ignored. However, deliberate hits against the floor are treated as "dishonest fencing" and penalized accordingly (see "The Practice of Fencing" below).

In the pre-electric era, épéeists used a point d'arret, a three-pronged point with small protruding spikes, which would snag on the opponent's clothing or mask, helping the referee to see the hits. The spikes caused épée fencing to be a notoriously painful affair, and épéeist could be easily recognized by the tears in their jacket sleeves. These days, the adherents of the point d'arret are few and far between, and non-electric weapons are generally fitted with foil-style rubber buttons.

Épée fencing tends to be more conservative in style than the other weapons, and bouts tend to be somewhat more deliberate and slow-paced.

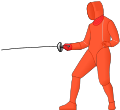

Sabre

Main article: Sabre (fencing)

The sabre is the "cutting" weapon, with a curved guard and a triangular blade. However, in modern electric scoring, a touch with any part of the sabre, point, flat or edge, as long as it is on target, will register a hit.

The modern sabre took its origins and traditions from the cavalry sabre. It is believed that the Hungarians introduced sabre fencing in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. Their sabre, derived from oriental scimitars, had a flat, slightly curved blade and was not as wide and thick as the French cavalry sabre. The Hungarians could not perfect their sabre until they were influenced by the Italian school, which helped them to perfect their teaching.

The target area in sabre is everything from the waist up, except for the hands.

Like foil fencing, sabre fencing uses right of way rules. However, the definition of an "attack" is different for the two weapons, and as a result, the right of way rules distinguish sabre and foil significantly. Sabre right of way rewards very fast fencing (on offense and defense), and so sabre fencing tends to be more aggressive in style than the other weapons.

Unlike in foil and épée fencing, the forward crossover (one foot of the fencer passing in front of the other) has been disallowed, as before both fencers could simply run and jump at each other at the start of a touch. This was done to improve the aesthetic qualities of the sport, in other words, to make it more appealing and interesting for the audience. It also provided a greater art to the sport for the fencer. Today, some sabre fencers use a "flying lunge", or "flunge" to produce a similar result without crossing over, but much of sabre fencing stays entirely on the ground.

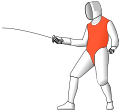

Protective clothing

Not pictured: socks and shoes

The clothing which is worn in modern fencing is made of tough cotton or nylon. Kevlar was added to top level uniform pieces (jacket, knickers, underarm protector, and the bib of the mask) following the Smirnov incident at the 1982 World Championships in Rome. However, kevlar breaks down in chlorine and UV light, so the act of washing one's uniform and/or hanging it up in the sun to dry actually damaged the kevlar's ability to do the job.

In recent years other ballistic fabrics such as Dyneema have been developed that perform the puncture resistance function and which do not have kevlar's weakness. In fact, the FIE rules state that the entirety of the uniform (meaning FIE level clothing, as the rules are written for FIE tournaments) must be made of fabric that resists a force of 800 newtons (1600N in the mask bib)

. The complete fencing kit includes the following items of clothing:

- Form-fitting jacket, covering groin and with strap (croissard) which goes between the legs

- Under-arm protector (plastron) which goes underneath the jacket and provides double protection on the sword arm side and upper arm. It is required to not have a seam in the armpit, which would line up with the jacket seam and provide a weak spot.

- Glove, with a gauntlet that prevents swords going up the sleeve and causing injury, as well as protecting the hand and providing a good grip

- Breeches (knickers), which are a pair of trousers. The legs are supposed to hold just below the knee.

- Knee-length socks, which cover the rest of the leg.

- Mask, including a bib which protects the neck. For competition, the bib must be sewn into the mask frame to eliminate a hole that might admit a blade. Thus, masks with snap-in bibs are not legal for competition.

- Plastic chest protector, mandatory for female fencers to provide protection for the breasts. While male versions are also available, they were, until recently, primarily worn by instructors, who are hit far more often during training than their students. Since the change of the depression timing (see above), these are increasingly popular in foil, as the hard surface increases the likelihood of point bounce and thus a failure for a hit to register. Plastrons are still mandatory, though.

Traditionally, the uniform is white in colour. This is primarily to assist the judges in seeing touches scored (black being the traditional colour for masters), but rules against non-white uniforms may also have been intended to combat sponsorship and the commercialization of the sport. However, recently the FIE rules have been relaxed to allow coloured uniforms. The colour white might also be traced back to times before electronic scoring equipment, when the blades were sometimes covered in soot or coloured chalk to make a mark on the opponent's clothing.

- Fencing Masters wear a heavier protective jacket, usually reinforced by plastic foam to endure the numerous hits an instructor has to endure.

- Sometimes in practice, masters wear a protective sleeve or a leg leather for protection of their fencing arm or leg.

Practice

The following description pertains to the practice of modern competitive fencing, as governed by the FIE and does not cover the many variations such as fencing within a circle popular with SCA enthusiasts.

Piste

A fencing bout takes place on a strip, or piste, which, according to the current FIE regulations, should be between 1.5 and 2 meters wide and 14 meters long. Two meters either side of the mid-point, there are two en-garde lines, where the fencers stand at the beginning of the bout. There are also two warning lines two metres from either end of the strip, to let a retreating fencer know that he is nearly out of space. Retreating off of the strip scores a touch for the opponent.

Participants

There are at least three people involved: two fencers and a referee.

The referee may be assisted by two or four side-judges. This was common practice prior to the introduction of electronic scoring. Their function is somewhat similar to that of linesmen in soccer. Their primary job used to be to watch for hits scored. Consequently, the arrival of the electronic scoring apparatus has rendered them largely redundant. Under current FIE rules, a fencer may ask for two side-judges (one to watch him, one to watch his opponent)or request another director, if he thinks that the referee is failing to notice some infringement of the rules on his opponent's part (such as use of the unarmed hand, substitution of the valid target area, breaching the boundary of the piste etc.).

Protocol

The referee stands at the side of the piste. The fencers walk on piste fully dressed, aside from the mask. If necessary, they plug their body wires into the spools connected to the electronic scoring apparatus and test that their weapons against each other, to make sure everything is functioning. They then retreat to their en-garde lines.

Prior to starting a bout, the fencers must salute each other. Refusal to do so can result in a fencer's suspension or disqualification. They must also salute the president (referee) and their audience. In non-electric events the 4 judges are saluted also. There are many variations of the salute, including some fairly theatrical ones, but the common theme is that the fencer stands upright, mask off, facing whomever he is saluting and raises his sword to a vertical position with the guard either at or just below face level, and then lowers it again. Various apocryphal stories about the origin of the salute circulate, like gladiators saluting each other in the arena, crusaders pointing their sword heavenward in pre-battle prayer, duellists showing each other that their swords are the same length, etc. The most likely source of the modern fencing salute is the "Present arms" command from military drill, which originated in the 16th century.

After the salutes are completed, the referee will call "En-garde!" The fencers put on their masks and adopt the fencing stance with the front foot behind the en-garde line and the blade in one of the orthodox fencing positions (generally sixte). They are now in the on-guard (en-garde) position. The referee then calls "Ready?" In some countries, the fencers are required to confirm that they are. Finally the referee will call "Play!" or "Fence!", and the bout will start. (In some circles, beginning the bout with the order "fence" is deemed incorrect and is contrary to the rules in certain countries). To interrupt the bout the referee calls "Halt!". A bout may be interrupted for several reasons: a hit has been scored, the rules have been breached, the situation is unsafe, or the action has become so disorganized that the referee can no longer follow it. Once the bout is stopped, the referee will, if necessary, explain his reasons for stopping it, analyse what has just happened and award points or give out penalites. If a point has been awarded, then the competitors return to their en-garde lines; if not, they remain approximately where they were when the bout was interrupted. The referee will then restart the bout as before. If the fencers were within lunging distance when the bout was interrupted and they are not required to return their en-gard lines, the referee will ask both fencers to give sufficient ground to ensure a fair start. A common way of establishing the correct distance is to ask both fencers to straighten their arms and to step back to the point where their weapon tips are almost touching.

This procedure is repeated until either one of the fencers has reached the required number of points (generally, 1, 5, 10 or 15, depending on the format of the bout) or until the time allowed for the bout runs out.

Fencing bouts are timed: the clock is started every time the referee calls "Play!" and stopped every time he calls "Halt!". The bout must stop when the designated time has been reached (this again, varies, depending on the format of the bout, three minutes to every five points is the norm). If the bout goes to full time, the fencer who has scored more hits wins. If the fencers are drawn at full time, they will be given a minute of extra time. At the beginning of that minute a coin will be tossed to decide who is going to win if neither fencer scores during it.

Priority ("right of way") rules

Foil and sabre are governed by priority rules, according to which the fencer who is the first to initiate an attack or the last to take a successful parry receives priority. When both fencers hit more or less simultaneously, only the fencer who had priority receives the point. If priority cannot be assigned unambiguously, no points are awarded. These rules were adopted in the 18th century as part of teaching practice. Their aim is to encourage "sensible" fencing and reward initiative and circumspection at the same time, in particular to reward fencers for properly made attacks, and penalize fencers for attacking into such an attack that lands, an action that could be lethal with sharp blades. The risk of both duellists charging onto one another's swords is kept to a minimum. At least in principle, in a prolonged phrase, the initiative passes smoothly from one fencer to the other, and back again, and so on. In practice most phrases are broken off quickly if neither fencer lands.

Despite the simplicity of the underlying principles, priority rules are somewhat convoluted, and their interpretation is a source of much acrimony. Much of this acrimony is centered on the definition of attack. According to the FIE rules, an attack is defined as "the initial offensive action made by extending the arm and continuously threatening the opponent's target..." The general consensus is that the referee should look for whose arm starts straightening first. In practice, referees, especially inexperienced ones, may go for the easy option and give priority to whichever fencer happened to be moving forwards. This is wrong, but, unfortunately, it is far from unusual. There is also a school of thought, subscribed to by a relatively small minority, that priority should be given to the fencer who was the first to straighten his arm fully. This, again, is out of line with the current rules. The adherents argue that this is the more classical way of doing things, but this claim is somewhat dubious, as actual practice decades ago based right of way on which fencer started straightening the arm (not which fencer completed the extension); and the reworded rules conform better to actual, traditional practice.

It is clear that an attack which has failed (i.e. has missed or been parried) is no longer an attack. The priority then passes to the defending fencer; he is now free to launch a riposte (if he has just parried an attack) or a counterattack (if the attack missed of its own accord). Whatever he choses to do, he must do it immediately, as hesitation also leads to loss of priority. A hesitant defender may lose priority and get hit with a renewal of the initial attack.

A parry, just like an attack, to be counted as valid must fulfill certain criteria. In foil any action that deflects a linear attack from its passage towards the target (i.e. temporarily removes the threat by deviating the point from the target) or breaks the momentum of an attack deliverd by a swinging motion will, generally, be given as a parry. Consequently, foilists often parry with a sharp beating motion which does not necessarily end in a full cover. In sabre, according to the FIE rules, "the parry is properly carried out when, before the completion of the attack, it prevents the arrival of that attack by closing the line in which that attack is to finish". In practice, when blades clash, sabre referees tend to look at the point of blade contact: contact of a defender's forte with an attacker's foible is generally counted as a parry, and the priority passes to the defender; whereas contact of a defender's foible with an attacker's forte is counted as a malparry, and the priority stays with the attacker. Some fencers refer to a retreat that makes an attack fall short as a "distance parry", but this is informal use: an actual parry requires blade contact.

Penalties

Modern fencing also includes the addition of cards/flags (or penalties). Each card has a different meaning. A fencer penalized with a yellow card is warned, but no other action is taken. A fencer penalized with a red card is warned, and a touch is awarded to his opponent. A fencer penalized with a black card is excluded from the competition, and may be excluded from the tournament, expelled from the venue, or suspended from future tournaments in the case of serious offenses.

Offenses are broken down into four group, and penalties are assesed based upon the group of the offense. Group 1 offenses include actions such as making bodily contact with the opposing fencer (in foil or sabre), delaying the bout, or removing equipment. The first group 1 offense committed by a fencer in a bout is penalized with a yellow card. Subsequent group 1 offenses committed by that fencer are penalized with a red card. Group 2 offenses include actions that are vindictive or violent in nature, or the failure to report to the strip with proper inspection marks on equipment. All group 2 offenses are penalized with a red card. Group 3 offenses include disturbing the order of a bout, or intentionally falsifying inspection marks. The first group 3 offense committed by a fencer is penalized with a red card, while any subsequent group 3 offense is penalized with a black card. Group 4 offenses include doping, manifest cheating, and other breaches of protocol, such as a refusal to salute. Group 4 offenses are penalized with a black card.

There is also a specific penalty for putting one or both feet off the side edge of the piste: halt is called, and the opponent may then advance one metre towards the penalised fencer. The penalised fencer must retreat to 'normal' distance before the bout can restart - that is, the distance where both fencers can stand on-guard, with their arms and swords extended directly at their opponent, and their blades do not cross. If this puts the fencer beyond the back edge of the piste, the fencer's opponent receives a point.

Electronic scoring equipment

Electronic scoring is used in all major national and international, and most local, competitions. At Olympic level, it was first introduced to épée in 1936, to foil in 1956, and to sabre in 1988. There are, however, still traditionalists within the fencing community who have fundamental objections to the practice (discussed later on in this section).

The central unit of the scoring system is commonly known as "the box". In the simplest version both fencers' weapons are connected to the box via long retractable cables. The box normally carries a set of lights to signal when a touch has been made. (Larger peripheral lights are also often used.) In foil and sabre, because of the need to distinguish on-target hits from off-target ones, special conductive clothing must be worn. This includes a jacket of conducting (lamé) cloth (for both weapons) and (in the case of sabre) a conducting mask and cuff (manchette).

Recently, reel-less gear has been adopted for sabre at top competitions, including the Athens Olympics. In this system, which dispenses with the spool (by using the fencer's own body as a grounding point), the lights and detectors are mounted directly on the fencers' masks. For the sake of the audience, clearly visible peripheral lights triggered by wireless transmission may be used. However, the mask lights must remain as the official indicators, as FIE regulations prohibit the use of wireless transmitters in official scoring equipment, to prevent cheating. Plans for reel-less épée and foil have not yet been adopted because of technical complications.

In the case of foil and épée, hits are registered by depressing a small push-button on the end of the blade. In foil, the hit must land on the opponent's lame to be considered on-target. (On-target hits set off coloured lights; off-target hits set off white lights.) At high level foil and épée competitions, grounded conductive pistes are normally laid down to ensure that bouts are not disrupted by accidental hits on the floor. In sabre, an on-target hit is registered whenever a fencer's blade comes into contact with the opponent's lamé jacket, cuff or mask. Off-target hits are not registered at all in sabre. It has been proposed that a similar arrangement (non-registration of off-target hits) be adopted for foil. This proposal is due to be reviewed at the 2007 FIE Congress. In épée the entire body is on-target, so the subject of off-target hits does not arise (unless you count the hits which miss the opponet etirely and land on an ungrounded section of the floor - needless to say doing so on purpose is considered cheating). Finally the competitors weapons are always grounded so hits against an opponent's blade or coquille do not register.

In foil and sabre, despite the presence of all the gadgetry, it is still the referee's job to analyse the phrase and, in the case of simultaneous hits, to determine which fencer had the right of way.

"Electric" fencing has not been without its problems. One of the most talked about has been the registration of glancing hits in foil. Traditionally, a valid, "palpable" hit could only be scored, if the point were fixed on the target in such a manner, as would be likely to pierece the skin, had the weapon been sharp. However, the electric foil point (the push-button on the end of the blade) lacks directionality, so hits which arrive at a very high angle of incidence can still register. In the 1980s, this lead to a growing popularity of hits delivered with a whip-like action (commonly known as "the flick"), bending the blade around the opponent's parry. Many saw this as an unacceptable deviation from tradition. In fact, the disputes over the flick grew so bitter that a number of traditionalist advocated (and still continue to advocate) complete abandonment of electronic scoring as something detrimental to fencing as an art. In 2004-2005 the FIE brought in rule changes to address such concerns. The dwell time (the length of time the point has to remain depressed in order to register a hit) was increased from 1 millisecond to 15 milliseconds. This change has been rather controversial. While it has not eliminated the flick altogether, it has made it technically trickier thereby denting its popularity. However, there have been some serious problems with apparently "palpable" hits not registering. Moreover, the imperative to make clear "square-on" hits has lead to a number of unforeseen results, which, it has been argued, have made foil less rather than more classical. The following have been reported:

- Unwillingness to attack, leading to long periods of inactivity and loss of certain visually striking (but risky)maneuvers;

- Loss of popularity of the more sophisticated and technically demanding compound actions;

- A rise in the number of renewed offensive actions (at the expense of counter-ripostes) delivered with a decidedly unclassical pumping action;

- A rise in the number of counterattacks with avoidance (at the expense of ripostes);

- Increased popularity of unorthodox "cowering" on-guard positions among young fencers;

- Hard hitting.

Having said that, every one of the above claims is a subject of dispute.

In sabre, the inadequacy of existing sensors has made it necessary to dispense with the requirement that a cut must be delivered with either the leading or the reverse edge of the blade and that, once again, it must arrive with sufficient force to have caused an injury had the blade been sharp (but not so forcefully to injure your opponent with a blunt weapon!) At present, any contact between the blade and the opponent's target is counted as a valid hit. Some argue that this has reduced sabre to a two-man game of tag; others argue that this has made the game more sophisticated.

The other serious problem in sabre (universally acknowledged as a problem) is that of "whip-over." The flexibility of the blades is such that the momentum of a cut can often "whip" the end of the blade around the defender's parry. The low success rate of parries (compared to other weapons) is seen by many as impoverishing the tactical repertory of the weapon. In 2000 the FIE brought in rule changes requiring stiffer blades. This has improved matters but not eradicated the problem altogether. There has been talk of making the sabre guard smaller, in order to make attacks on preparation and counterattacks easier and thus slow down the momentum of the attack, giving the defender more of a chance.

Finally, the cut-out times deserve a mention. The cutout time is the maximum time allowed by the box between two hits registering as simultaneous (if this time is exceeded, only one light will appear). In épée this time is very short: 40 milliseconds. This means that, so far as human perception is concerned, the hits really do need to arrive at the same instant. In foil and sabre, where priority rules apply, the cutout times are considerably longer (hundreds of milliseconds). This was a source of two problems:

- Double lights are a frequent occurrence, making refereeing difficult. Too many decisions are disputed.

- Once again, the attacker gains an unreasonable advantage. It is possible to execute a long marching attack with only a hint of an arm extension, clearly inviting an attack on preparation, which is then followed by a delayed trompment.

For those reasons, in 2004-2005 the FIE slashed the cut-out times for foil and sabre from 750 milliseconds to 350 milliseconds and from 350 milliseconds to 120 milliseconds respectively. While these changes were controversial at first, the fencing community now seems to have accepted them. Some concerns remain at sabre, where immediate renewals frequently "time out" indirect ripostes.

Non-electronic scoring

Prior to the introduction of electronic scoring equipment, the president of jury was assisted by four judges. Two judges were positioned behind each fencer, one on each side of the strip. The judges watched the fencer opposite to see if he was hit.

When a judge thought he saw a hit, he raised his hand. The president (referee or director) then stopped the bout and reviewed the relevant phases of the action, polling the judges at each stage to determine whether there was a touch, and (in foil and sabre) whether the touch was valid or invalid. Each judge had one vote, and the president had one and a half votes. Thus, two judges could overrule the president; but if the judges disagreed, or if one judge abstained, the president's opinion ruled.

Épée fencing was later conducted with red dye on the tip, easily seen on the white uniform. As a bout went on, if a touch was seen, a red mark would appear. Between the halts of the director, judges would inspect each fencer for any red marks. Once one was found, it was circled in a dark pencil to show that it had been already counted. The red dye was not easily removed, preventing any cheating. The only way to remove it was through certain acids such as vinegar. Thus, épée fencers became renowned for their reek of vinegar until the invention of electronic equipment.

Footwork

In a fencing bout, a great deal depends on being in the right place at the right time. Fencers are constantly maneuvering in and out of each other's range, accelerating, decelerating, changing directions and so on. All this has to be done with minimum effort and maximum grace, which makes footwork arguably the most important aspect of a fencer's training regime. In fact, in the first half of the 20th century it was common practice to put fencers through six months to a year of footwork before they were ever allowed to hold a sword. (For better or for worse, this practice has now been largely abandoned.)

Modern fencing tends to be quite linear. To some extent this may be dictated by the practicalities of fitting the maximum number of fencers into a finite size gym and hooking them up to the electronic scoring apparatus. The main reason, however, is that the weapons are light and easy to redirect. Sideways movement, which was a common defense against an attack with a comparatively unwieldy weapon like the rapier, is now a pretty unreliable tactic against a competent opponent. These days, defense by footwork usually takes the shape of moving either directly away from your opponent (out of his range) or directly towards him (making the attack "overshoot").

The way fencers stand and move often appears artificial to a novice, but it has evolved over centuries of trial and error and is, in fact, extremely pragmatic. The most basic requirement is to face your opponent in such a way that your weapon offers you maximum protection and your opponent maximum threat. Consequently fencers tend to stand somewhat side-on to the principal direction of movement (the fencing line), leading with the weapon side (right for a right-hander, left for a left-hander). In foil and épée this has the added advantage of presenting the opponent with a sloping target surface, making it more difficult for him to land a sound hit. The second most important requirement is to maintain balance and ease of movement. In the fencing stance the feet are a shoulderwidth or more apart giving a wide base. They are also placed at right angles to one another: the front foot points along the fencing line, and the back foot perpendicular to it. This allows the fencer to "shuffle" backwards and forwards, which is the most common mode of movement (more about that in the next paragraph). Finally, the knees are well bent and the centre of gravity is kept mid way between the heels. The fencer is now in a position where he is well balanced, able to use his leg muscles to generate rapid bursts of speed and change directions with comparative ease.

As was already mentioned, fencers tend to move with series of "shuffling" steps, which allow them to stay in the fencing stance. In order to move forwards, the fencer picks up his front foot, puts it down a few inches ahead of its original position, then picks up his back foot and moves it by the same amount. To move backwards, the procedure is reversed. The order in which the feet are moved is important, and, if the fencer gets it wrong, he may end up with a dangerously narrow and unbalanced stance half way through the step. Having said that, like all rules, this one can sometimes be broken to great effect.

The most common way of delivering an attack in fencing is the lunge, where the fencer kicks out with his front foot and rapidly straightens his back leg. This maneuver has a number of advantages: it is faster than a step, it allows the fencer to keep his own body as far away from the opponent as is possible without losing balance, and it is comparatively easy to return into the fencing stance. On the downside, the lunge puts the fencer in a comparatively static position, and any further movement backwards or forwards, while by no means impossible, does require extra effort.

Sometimes fencers do take the more "natural" kind of steps, where the back foot passes the front foot. These are usually referred to as cross-steps. While cross-steps do have the advantage of range and speed, they put a fencer in an awkward and frequently unbalanced position mid-step, which is why experienced fencers tend to use them sparingly. A somewhat exaggerated version of the cross-step, sometimes used to deliver an attack in foil or épée, is the flèche ("arrow" in French). In the flêche, the fencer leans forward and takes a long running cross-step, generating most of the thrust with his front leg. Ideally, the hit delivered with a fléche should arrive as or just before the fencer's front foot hits the ground. The best way to defend against this attack is by the use of a cedeing parry. This is where the defending fencer steps back whilst parrying his opponent's blade. This move is effective when performed well and can also turn the flêche to the defendant's advantage. When (as often happens) the flêching fencer runs past the defender after a cedeing parry, the defender can pivot 180° on their rear foot and hit the attacking fencer on the back in one swift movement. This movement is hard to perform and requires alot of practice as it is only legal when performed in one movment, otherwise the fencer would be penalised for turning their back. In sabre cross-steps have been prohibited since the 1990s, because they make for very boring fencing. In a real fight (one involving sharp weapons), a running attack would be an extremely risky thing to try: there is always the possibility of a last-minute counterattack with both fencers ending up dead. Because of the priority rules (and the fact that the weapons are blunt), this issue does not come up in competitive sabre. Given the large scoring surface (the entire blade), a well delivered running attack is nigh impossible to defend against — it is impossible to move backwards fast enough.

Variations and portions of the above movements can also be used by themselves. For example, a check-step forward is performed by moving the back foot as in a retreat, then performing an entire advance. This maneuver can trick your opponent into thinking that you are retreating, when in reality you are about to close distance.

Other footwork actions include the appel (French for "call"), which is a stomp designed to upset the opponent's perception of rhythm, and the ballestra, which is a "hopping" step commonly used as a preparation for attacks (the back foot leaves the ground, while the front foot is still in mid-air; both feet come down at the same time).

National governing bodies

- Argentina

In Argentina, the sport of fencing is governed by the Federación Argentina de Esgrima (FAE). Information about this organization can be found here: www.austedes.com.ar.

- Australia

Australia has the Australian Fencing Federation (AFF). The organization's website is located here: Australian Fencing Federation

- Estonia

In Estonia, the sport of fencing is governed by Eesti Vehklemisliit (EVL). The organization's website is located here: Eesti vehklemisliit.

- France

In France, the sport of fencing is governed by the Federation Francaise d'Escrime (FFE). The organization's website is located here: Federation Francaise d'Escrime.

- Hungary

In Hungary, the sport of fencing is governed by the Magyar Vívószövetség (MVSz). The organization's website is located here: Magyar Vívószövetség

- Ireland

The sport of fencing in Ireland is governed by the Irish Amateur Fencing Federation.

- Italy

In Italy, the sport of fencing is governed by the Federazione Italiana Scherma (FIS). The organization's website is located here: Federazione Italiana Scherma.

- Mexico

In Mexico, the sport of fencing is governed by the Federacion Mexicana de Esgrima (FME). Clubs affiliate to each state's association, who are affiliated with the FME.

- New Zealand

In New Zealand, the sport of fencing is governed by Fencing New Zealand (FeNZ)

- United States

In the United States, the sport of fencing is governed by the United States Fencing Association (USFA).

- United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, fencing is governed by the British Fencing Association (BFA). The 'Home Nations' of Wales, England, Northern Ireland and Scotland have their own governing bodies under the auspices of the BFA: Welsh Fencing, England Fencing, the Northern Ireland Fencing Union and Scottish Fencing respectively.

Collegiate fencing

Colligiate fencing has existed for a long time in the US. Some of the earliest programs came from the Ivy League schools, but now there are over a hundred fencing programs nation wide. Both clubs and varsity teams participate in the sport, however only the varsity teams may participate in the NCAA championship tournament. Due to the lack of schools in fencing, the teams actually fence inter-division (teams from Division III schools to Division I), and all divisions participate in the NCAA Championships. In 2006 Harvard edged out Penn State to win their first national championship in the sport.

Collegiate fencing tournaments are "team tournaments" in a sense, but contrary to what many people expect, collegiate meets are not run as 45-touch relays. Schools compete against each other one at a time. In each weapon and gender, three fencers from each school fence each other in five-touch bouts. (Substitutions are allowed, so more than three fencers per squad can compete in a tournament.) A fencer's individual results in collegiate tournaments and regional championships are used to select the fencers who will compete in NCAA championships. Individual results for fencers from each school are combined to judge the school's overall performance and to calculate how it placed in a given tournament.

Notable Fencers

Fencers and coaches of the Olympic era

Belarus

- Elena Belova (Novikova) - foilist, one of the greatest fencers of the Soviet era, 1968 individual Olympic Champion, 1969 individual World Champion, member of the winning Soviet team at the 1968,1972 and 1976 Olympics and the 1970, 1971 and 1974 World Championships.

- Alexandr Romankov - foilist, one of the most successful Soviet fencers, regarded by some as the greatest foilist of the 20th century

- Viktor Sidjak - an extremely successful sabreur from the Soviet era, Olympic (1972) and World (1969) Champion, winner of the 1972 and 1973 World Cup, also a member of the winning team at the 1968, 1976 and 1980 Olympics and at the 1969, 1970, 1971, 1974, 1975 and 1979 World Team Championships, pupil of David Tyshler

China

- Ju-Jie Luan - Chinese fencer and coach, gold medallist for Women's Foil at the 1984 Summer Olympics

Estonia

- Svetlana Chirkova-Lozovaja - The most succesful Estonian fencer at the Soviet era. Olympic gold medal for Women's Foil team event at the 1968 Summer Olympics, World champion at the Women's Foil team event at 1971, silver 1969, individual World Championships bronze medal 1969.

- Kaido Kaabermaa - Estonian épéeist, bronze (1990) and gold (1991) at the World Championships team event (as a part of Soviet Union team). Individual World Championships bronze (1999).

France

- Lucien Gaudin - twice World Champion (1905 and 1918), won four Gold and three Silver Olympic medals covering all three weapons

- Christian d'Oriola - 4 times world champion, 2 olympic titles plus many team titles

- Laura Flessel-Colovic

Germany

- Helene Mayer - a German-Jewish foilist, won Gold at the 1928 Summer Olympics and the 1929 World Chamnpionship, left for the US in 1931, returned to represent Germany in the 1936 Summer Olympics and won Silver, went back to the US and was granted US citizenship, returned to Germany in 1952 and died of cancer in 1953, won the US Championships a total of eight times

Great Britain

- Richard Cohen - a five time British sabre Champion, best known today as the author of "By the Sword", a highly acclaimed book on the history of fencing

- Richard Kruse - foilist, the most successful male British fencer for several decades, reached the quarter-finals (L8) at the 2004 Summer Olympics, pupil of Ziemowit Wojciechowski

- James Williams - sabreur, reached L16 at the 2000 Summer Olympics, known for his flamboyant fencing style and unbelievable fitness levels, recently retired from competitive fencing

Hungary

- Péter Fröhlich - Hungarian master and Olympic coach

- Aladar Gerevich - Hungarian sabreur who is the only athlete to win the same Olympic event six times.

- Rudolf Karpati - six time Olympic and seven time World sabre Chapion

- László Szabó - the Hungarian master who defined a system for developing coaches and wrote "Fencing and the Master", the only direct student of the legendary Italo Santelli to write of what he learned. Teacher of Olympic and World champions.

- Bela Valter - Hungarian master and Olympic coach

- Imre Vass - authored a widely read guide to épée fencing

- Francis Zold (1904-2003) - Hungarian fencing master and a legendary promoter and teacher of fencing in the post-war US; a student of Italo Santelli, he served as captain of the Hungarian fencing team at the London Olympics in 1948. He emigrated to the United States following the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 and worked as a fencing coach at a number of colleges and universities, including the University of Southern California and Pomona College in Claremont, CA. He died in 2003 at the age of 99.

Italy

- Edoardo Mangiarotti of Italy has won more Olympic titles and World championships than any other fencer in the history of the sport, a member of the Mangiarotti fencing clan.

- Aldo Nadi - won gold and silver medallist at the 1920 Olympics, during the Mussolini years emigrated to the US, where he penned the influential "On Fencing" and his autobiographical notes entitled "The Living Sword", son of Beppe Nadi and brother of Nedo Nadi

- Nedo Nadi - won 6 Olympic Gold medals: three foil, two sabre and one épée, son of Beppe Nadi and brother of Aldo Nadi

- Giorgio Santelli - born in Hungary, son of Italo Santelli, won Gold at the 1920 Olympics as part of the Italian sabre team, emigrated to the US in 1924, coach to 5 U.S. Olympic teams, legendary fencing teacher and popularizer, founder of the Santelli salle in New York City.

- Italo Santelli - the fencing master who revolutionized sabre fencing and developed the modern Hungarian style in the 1920s.

Poland

- Zbigniew Czaikowski - a highly respected coach, coached the Polish national squad for many years, has written over 25 books, has successful pupils in all weapons, including Egon Franke, Elżbieta Cymerman, Jacek Bierkowski, Bogdan Gonsior, Magda Jeziorowska.

- Ziemowit Wojciechowski - three time Champion of Poland, member of the Polish Olympic squad at the 1976 Olympics, defected to Great Britain in 1978, where he is renowned as a successful coach, pupils include Richard Kruse, Lawrence Halsted and Camille Datoo. As of 2005 he teaches part-time at Highgate School, London.

Russia

- Serguei Charikov - sabreur, a member of the winning Russian team at the 1996, 2000 and 2004 Olympics and the

- Pavel Kolobkov - épéeist, Olympic Champion 2000, five times World Champion (1991, 1993, 1994, 2002, 2003), twice Junior World Champion (1987, 1988), winner of the 1999 World Cup

- Viktor Krovopouskov - sabreur, four-time Olympic Gold medalist (1976 and 1980 individual and team), twice individual World Champion (1978, 1982), twice winner of the World Cup (1976, 1979)

- Mark Midler - foilist, a member of the first generation of internationally successful Soviet fencers, took Gold at 1956 and 1960 Olympics as a part of the Soviet team, won four consecutive World Championships (1959-1962).

- Vladimir Nazlymov - sabre fencer/coach, won the individual World Championship in 1975 and 1979 and the World Cup in 1975 and 1977, took team Gold at the 1968, 1976 and 1980 Olympics and at the 1967, 1969-1971, 1974, 1975, 1977, 1979 World Championships, twice named the world's best sabre fencer by the FIE, currently head fencing coach of The Ohio State University fencing team.

- Boris Onishchenko - modern pentathlete, individual silver medallist and team gold medallist in 1972, disqualified in 1976 for using a rigged weapon

- Stanislav Pozdniakov - sabreur, Olympic (1996) and World (1997, 2001, 2002) Champion, seven times winner of the World Cup (1994-1996, 1999-2002), member of the winning Russian sabre team at the 1992, 1996, 2000 and 2004 Olympics and at the 1994, 2001, 2002 and 2003 World Championships

- Mark Rakita - sabreur, twice Olympic Champion (1964, 1968), World Champion in 1967, David Tyshler's pupil and a highly successful coach in his own right (pupils include Victor Krovopouskov, Michail Burtsev and Victor Sidjak)

- Yakov Rylsky - sabreur, twice Olympic (1964, 1968) and three times World (1958, 1961, 1963) Champion, represented the USSR over a period of 14 years (1953-1966)

- Vladimir Smirnov - foilist, won individual Gold at the 1980 Summer Olympics, won the world championships in 1981, died at the 1982 World Championships in Rome, when a broken blade went through his mask causing a fatal brain injury (through the left eye orbit--not the eye itself); his death prompted an extensive review of safety standards in fencing. Most notably it prompted stronger masks (the mesh must withstand a 12kg probe on a regular mask, 25kg on an FIE mask. Smirnov's mask at the time of his injury was less than half as strong as the non-FIE masks of today when he obtained it. By the time of his injury, it had likely deteriorated from use and was even weaker) 800 Newton resistant fabric in the jacket, underarm protector, and knickers (1600N in the mask bib) maraging steel blades in foil and epee (which, contrary to fencing urban myth, are not designed to "break flat". They simply break less frequently than carbon steel blades) and various rules re-clothing overlap and placement of zippers and seams. All of these changes were designed to minimize the chance of a blade getting through the protective clothing. Tragic though his death was, it ultimately resulted in making the sport statistically safer than golf.

- David Tyshler - sabreur, a member of the first generation of internationally successful Soviet fencers, won medals at the 1956 Olympics and five World Championships, best known for his achievements as a coach, one of the founding fathers of the Soviet school of fencing, pupils include Mark Rakita, Victor Sidjak and Victor Krovopouskov

South Korea

- Young Ho Kim - Olympic foil Champion 2000. Additionally, was down 11-3 to Sergei Golubitsky in the third and final period of the men's foil gold medal bout at the 1997 World Championships. Since the necessary score to reach to win was 15 touches, most people would consider Kim to be fencing for pride at this point. Instead, he rallied and scored 8 touches in a row on Golubitsky -- seven of them being one-light hits -- to tie it up at 11 all. They then traded touches until Golubitsky won his first of three world titles 15-14...surely the most heroic loss at any world championsip.

Ukraine

- Sergei Golubitsky - World foil Champion 1997, 1998, 1999, Winner of the 1992, 1993, 1994 and 1999 World Cup

USA

- Albert Axelrod, bronze medallist in the 1960 Summer Olympics in Foil

- Daniel Bukantz, Olympian, U.S. Foil Fencer, Member of the Jewish Sports Hall of Fame

- Gay Jacobsen D'Asaro, 1976, 1980 Olympian U.S. Women's Foil Fencer (now Gay MacLellan)

- Michael D'Asaro Sr.

- Csaba Elthes, legendary coach to 6 U.S. Olympic teams, immigrated from Hungary

- Nick Evangelista, specializes in early 20th Century fencing, calling it 'classical' to distinguish it from current sport fencing.

- Fred Linkmeyer

- Michael Marx 5 x Olympian, Epee and Foil Coach, National Champion

- Sharon Monplasir

- Sada Jacobson, bronze medallist in the 2004 Summer Olympics in Sabre; first American female to be ranked #1 in the world, and the second American ever to be ranked #1 in the world.

- Ed Korfanty, U.S. National women's sabre team coach, formerly Polish national coach, coach to 7 x Jr. World Sabre Champion Mariel Zagunis, 2004 Cadet Sabre champion, Caitlin Thomas, coach to 2000 and 2005 U.S. World Champion sabre team. Coach to 2004 Olympic Gold medallist Mariel Zagunis. 2002 and 2003 World Veterans Champion in Men's sabre.

- Janice Romary, 1948, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1964, 1968 Olympian U.S. Foil Fencer

- Keeth Smart, first American to be ranked #1 in the World, member of 2004 gold medal US Men's Sabre team at World Cup

- Rebecca Ward, sabre student of U.S. National Coach Ed Korfanty. 2005 FIE Jr. World Champion at age 15. Part of the U.S. Sr. Women's Sabre team that took the 2005 World Championship title in Leipzig, Germany Oct. 2005 (other members were Sada Jacobson, Caitlin Thompson and Olympic Champion Mariel Zagunis. 2006 Cadet World Champion, 2006 Jr. World Champion, 2006 Jr. World Champion Team member, 2nd fencer in history to win 3 world titles in one season (Team-mate Zagunis was the first).

- Peter Westbrook, bronze medallist in the 1984 Summer Olympics, 13-time US National Men's Sabre Champion, author of Harnessing Anger, founder of the Peter Westbrook Foundation, teaching and helping youth through sport.

- Mariel Zagunis, gold medallist in the first ever Women's Sabre event at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Sabre; first American woman to win gold; first American to win gold since 1904

Fencing masters of the pre-Olympic era

- Camillo Agrippa

- Domenico Angelo

- Rocco Bonetti

- Ridolfo Capo Ferro

- Guillaume Danet

- Salvatore Fabris

- Giacomo di Grassi

- Achille Marozzo

- Thibault Girard

- Vincentio Saviolo

- George Silver

- Andre Wernesson

Famous duellists and fencing enthusiasts

- José Rizal

- Otto von Bismarck

- Tycho Brahe

- George Byron

- Winston Churchill

- René Descartes

- Bruce Dickinson

- Albrecht Dürer

- Jean-François Lamour

- Benito Mussolini

- George S. Patton - General and U.S. Army Master of the Sword. Designer of the M1913 Cavalry Saber. 1912 Stockholm Olympics in the first modern pentathlon competition (Ranked 1st in fencing - 8th overall).

- Theodore Roosevelt

- Stephen Kaufer

Members of the contemporary classical fencing community

- Miguel Andrade Gomes - Portugal

- David Achilleus

- Alberto Bomprezzi

- Adam A. Crown

- William Gaugler

- Neville Gawley

- Sean Hayes

- Tom Leoni

- Paul MacDonald

- Ramon Martinez

- Andrea Lupo Sinclair

- Chris Umbs

Members of the Historical fencing community

See also

- Academic fencing

- Fencing terminology

- List of American epee fencers

- List of American sabre fencers

- List of American foil fencers

- USFA Hall of Fame

- Kendo

External links

- Governing bodies

- Fédération Internationale d'Escrime The body responsible for all international fencing

- Association for Historical Fencing An international organization for traditional (classical & historical) fencing

- U.S. Fencing Coaches Association

- U.S. Fencing Association web site

- Canadian Fencing Federation

- British Fencing Association

- Australian Fencing Federation

- Spanish Fencing Federation

- Balearic Fencing Federation

- Dutch Fencing Federation KNAS

- Italian Fencing Federation FIS

- Hungarian Fencing Association

- Estonian Fencing Association

- Other sites

- Fencing.Net comprehensive fencing news site featuring articles on the state of the game, as well as an active forum for fencing discussion

- Fencing Forum UK based fencing forum for fencing discussion

- Fencing Directory

- Classical Fencing and Historical Swordsmanship Resources An extensive directory of traditional fencing groups and prominent individuals listed by geographic location

- Photos of Asian Fencing Championships in Borneo

- Esgrimamex Mexican fencing website

- Fencing FAQ from rec.sport.fencing

- Classic books on fencing

- Fencing photo gallery

- National Fencing NFA is an official club member of the United States Fencing Associaten (USFA) and the New Jersey Division (NJUSFA). NFA specializes in men's and women's saber, foil and epee.

- FencingPhotos Official photographer of the International Fencing Federation

- AnyMartialArt.org Fencing overview

- Fencing Pictures

- FRED: Fencing Results and Events Database Site with current results for most tournaments in the U.S.A., as well as info on upcoming tournaments.

- The ARMA The official website of the Association for Renaissance Martial Arts (Historical Fencing)

- Australian Historical Swordplay Federation

- austedes.com.ar The argentine fencing site

- http://members.ozemail.com.au/~mprince/fencing/fencing.html The University of New South Wales Fencing Club Website

References

- Fence on Etymonline. Retrieved June 7, 2006.

- Homepage of OED online. Retrieved June 7, 2006.

- "Fencing: an Electric Scorer". The Lancet. 141 (3643): 37–38. 1896-06-24.