This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Ms Sarah Welch (talk | contribs) at 00:46, 16 June 2015 (c/u, add sources). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:46, 16 June 2015 by Ms Sarah Welch (talk | contribs) (c/u, add sources)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)This article is about the sacred sound and spiritual icon in Indian religions. For movies and other uses, see Om (disambiguation).

Template:Contains Indic text Om (or Auṃ Template:IPA-sa, Sanskrit: ॐ) is a sacred sound and a spiritual icon in Dharmic religions. It is also a mantra in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. In Hinduism, Om is a spiritual symbol (pratima) referring to Atman (soul, self within) and Brahman (ultimate reality, entirety of the universe, truth, divine, supreme spirit, cosmic principles, knowledge).

The symbol is one of the most important symbol in Hinduism, and is often found at the beginning and the end of chapters in the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Hindu texts. It is a sacred spiritual incantation made before and during the recitation of spiritual texts, during puja and private prayers, in ceremonies of rites of passages (sanskara) such as weddings, and sometimes during meditative and spiritual activities such as Yoga.

Om is part of the iconography found in ancient and medieval era temples, monasteries and spiritual retreats in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. A related symbol Ik Onkar is also found in Sikhism. The symbol has a spiritual meaning in all Indian religions, but the meaning and connotations of Om vary between the diverse schools within and across the various traditions.

The syllable is also referred to as omkara (ओंकार, oṃkāra), aumkara (औंकार, auṃkāra), and pranava (प्रणव, praṇava).

Etymology

The etymological origins of Om are unclear. Scholars consider Om to have been variously held as the "cosmic sound" or "mystical syllable" in ancient India, or simply as "affirmation to something divine", or as symbolism for abstract spiritual concepts in the Upanishads. It is found in most ancient layer of the Vedic texts such as the Rig Veda, dated to be from the 2nd millennium BCE. The hymn 1.1.1 of Rig Veda Samhita, for example, opens as

ॐ अग्निमीळे पुरोहितं यज्ञस्य देवमृत्विजम् । होतारं रत्नधातमम् ॥१॥

— Rigveda 1.1.1,

The syllable means "affirmation" in the Aranyaka layer of texts in the Vedas. Aitareya Aranyaka, for example, in verse 23.6, explains Om as an acknowledgment, melodic confirmation, something that gives momentum and energy to a hymn,

Om (ॐ) is the pratigara (agreement) with a hymn. Likewise is tatha (so be it) with a song. But Om is something divine, and tatha is something human.

— Aitareya Aranyaka 23.6,

Elsewhere in the Aranyaka and the Brahmana layers of Vedic texts, the syllable is so widespread and linked to knowledge, that it stands for the "whole of Veda". The etymological foundations of Om are repeatedly discussed in the oldest layers of the Vedic texts, as well the early Upanishads. Aitareya Aranyaka, in sections 5.32 to 5.34, for example suggests that the three phonetic components of Om (pronounced AUM) correspond to the three stages of cosmic creation, and when it is read or said, it celebrates those creative powers of the universe. The Brahmana layer of Vedic texts equate Om with Bhur-bhuvah-Svah, the latter symbolizing "the whole Veda". The Aitareya Brahmana offers various shades of meaning to Om, such as it being "the universe beyond the sun", or that which is "mysterious and inexhaustible", or "the infinite language, the infinite knowledge", or "essence of breath, life, everything that exists", or that "with which one is liberated". The Sama Veda, the poetical Veda, orthographically maps Om to the audible, the musical truths in its numerous variations (Oum, Aum, Ovā Ovā Ovā Um, etc) and then attempts to extract musical meters from it.

The syllable Om evolves to mean many abstract ideas in the earliest Upanishads. Max Muller and other scholars state that these philosophical texts recommend Om as a "tool for meditation", explain various meanings that the syllable may be in the mind of one meditating, ranging from "artificial and senseless" to "highest concepts such as the cause of the Universe, essence of life, Brahman, Atman, and Self-knowledge".

The syllable is also referred to as praṇava. Other used terms are akṣara (lit. symbol, character) or ekākṣara (lit. one symbol, character), and in later times omkāra becomes prevalent.

Om or Aum is also written ओ३म् (o̿m Template:IPA-sa), where ३ is pluta ("three times as long"), indicating a length of three morae (that is, the time it takes to say three syllables) — an overlong nasalised close-mid back rounded vowel —, though there are other enunciations adhered to in received traditions.

Hinduism

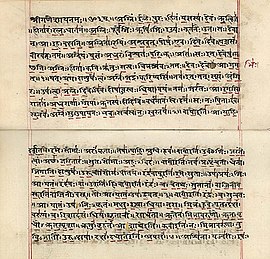

Om is a common symbol found in the ancient texts of Hinduism, such as in the first line of Rig veda (top), as well as a icon in temples and spiritual retreats.

Om is a common symbol found in the ancient texts of Hinduism, such as in the first line of Rig veda (top), as well as a icon in temples and spiritual retreats.

Vedic literature

The syllable "Om" is described with various meanings in the Vedas and different early Upanishads. The meanings include "the sacred sound, the Yes!, the Vedas, the Udgitha (song of the universe), the infinite, the all encompassing, the whole world, the truth, the ultimate reality, the finest essence, the cause of the Universe, the essence of life, the Brahman, the Atman, the vehicle of deepest knowledge, and Self-knowledge".

Vedas

The chapters in Vedas, and numerous hymns, chants and benedictions therein use the syllable Om. The Gayatri mantra from the Rig Veda, for example, begins with Om. The mantra is extracted from the 10th verse of Hymn 62 in Book III of the Rig Veda. These recitations continue to be in use, and m ajor incantations and ceremonial functions begin and end with Om.

ॐ भूर्भुवस्व: |

— Rig Veda III.62.10, Translated by Julius Lipner

तत्सवितुर्वरेण्यम् |

भर्गो देवस्य धीमहि |

धियो यो न: प्रचोदयात् ||

Om. Earth, atmosphere, heaven.

Let us think on that desirable splendour

of Savitr, the Inspirer. May he stimulate

us to insightful thoughts.

Chandogya Upanishad

The Chandogya Upanishad is one of the oldest Upanishads of Hinduism. It opens with the recommendation that "let a man meditate on Om". It calls the syllable Om as udgitha (उद्गीथ, song, chant), and asserts that the significance of the syllable is thus: the essence of all beings in earth, the essence of earth is water, the essence of water are the plants, the essence of plants is man, the essence of man is speech, the essence of speech is the Rig Veda, the essence of the Rig Veda is the Sama Veda, and the essence of Sama Veda is the udgitha (song, Om).

Rik (ऋच्, Ṛc) is speech, states the text, and Sāman (सामन्) is breath; they are pairs, and because they have love and desire for each other, speech and breath find themselves together and mate to produce song. The highest song is Om, asserts section 1.1 of Chandogya Upanishad. It is the symbol of awe, of reverence, of three fold knowledge because Adhvaryu invokes it, the Hotr recites it, and Udgatr sings it.

The second volume of the first chapter continues its discussion of syllable Om, explaining its use as a struggle between Devas (gods) and Asuras (demons). Max Muller states that this struggle between gods and demons is considered allegorical by ancient Indian scholars, as good and evil inclinations within man, respectively. The legend in section 1.2 of Chandogya Upanishad states that gods took the Udgitha (song of Om) unto themselves, thinking, "with this we shall overcome the demons". The syllable Om is thus implied as that which inspires the good inclinations with man.

Chandogya Upanishad's exposition of syllable Om in its opening chapter combines etymological speculations, symbolism, metric structure and philosophical themes.

Katha Upanishad

The Katha Upanishad is the legendary story of a little boy, Nachiketa – the son of sage Vajasravasa, who meets Yama – the Indian deity of death. Their conversation evolves to a discussion of the nature of man, knowledge, Atman (Soul, Self) and moksha (liberation). In section 1.2, Katha Upanishad characterizes Knowledge/Wisdom as the pursuit of good, and Ignorance/Delusion as the pursuit of pleasant, that the essence of Veda is make man liberated and free, look past what has happened and what has not happened, free from the past and the future, beyond good and evil, and one word for this essence is the word Om.

The word which all the Vedas proclaim,

— Katha Upanishad, 1.2.15-1.2.16

That which is expressed in every Tapas (penance, austerity, meditation),

That for which they live the life of a Brahmacharin,

Understand that word in its essence: Om! that is the word.

Yes, this syllable is Brahman,

This syllable is the highest.

He who knows that syllable,

Whatever he desires, is his.

Mandukya Upanishad

The Mandukya Upanishad opens by declaring, "Om!, this syllable is this whole world".Thereafter it presents various explanations and theories on what it means and signifies. This discussion is built on a structure of "four fourths" or "fourfold", derived from A + U + M + "silence" (or without an element).

Aum as all states of time

In verse 1, the Upanishad states that time is threefold: the past, the present and the future, that these three are "Aum". The four fourth of time is that which transcends time, that too is "Aum" expressed.

Aum as all states of Atman

In verse 2, states the Upanishad, everything is Brahman, but Brahman is Atman (the Soul, Self), and that the Atman is fourfold. Johnston summarizes these four states of Self, respectively, as seeking the physical, seeking inner thought, seeking the causes and spiritual consciousness, and the fourth state is realizing oneness with the Self, the Eternal.

Aum as all states of consciousness

In verses 3 to 6, the Mandukya Upanishad enumerates four states of consciousness: wakeful, dream, deep sleep and the state of ekatma (being one with Self, the oneness of Self). These four are A + U + M + "without an element" respectively.

Aum as all of knowledge

In verses 9 to 12, the Mandukya Upanishad enumerates fourfold etymological roots of the syllable "Aum". It states that the first element of "Aum" is A, which is from Apti (obtaining, reaching) or from Adimatva (being first). The second element is U, which is from Utkarsa (exaltation) or from Ubhayatva (intermediateness). The third element is M, from Miti (erecting, constructing) or from Mi Minati, or apīti (annihilation). The fourth is without an element, without development, beyond the expanse of universe. In this way, states the Upanishad, the syllable Om is indeed the Atman (the self).

The Epics

The Bhagavad Gita, in the Epic Mahabharata, mentions the meaning and significance of Om in several verses. For example, Fowler notes that verse 9.17 of the Bhagavad Gita synthesizes the competing dualistic and monist streams of thought in Hinduism, by using "Om which is the symbol for the indescribable, impersonal Brahman".

I am the Father of this world, Mother, Ordainer, Grandfather, the Thing to be known, the Purifier, the syllable Om, Rik, Saman and also Yajus.

— Krishna to Arjuna, Bhagavad Gita 9.17,

The significance of the sacred syllable in the Hindu traditions, is similarly highlighted in various of its verses, such as verse 17.24 where the importance of Om during prayers, charity and meditative practices is explained as follows,

Therefore, uttering Om, the acts of yajna (fire ritual), dana (charity) and tapas (austerity) as enjoined in the scriptures, are always begun by those who study the Brahman.

— Bhagavad Gita 17.24,

Puranic Hinduism

The medieval era texts of Hinduism, such as the Puranas adopt and expand the concept of Om in their own ways, and to their own theistic sects. According to the Vayu Purana, Om is the representation of the Hindu Trimurti, and represents the union of the three gods, viz. A for Brahma, U for Vishnu and M for Shiva. The three sounds also symbolise the three Vedas, namely (Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda).

The Shiva Purana highlights the relation between deity Shiva and the Pranava or Om. Shiva is declared to be Om, and that Om is Shiva.

Other views

Maheshwarananda suggests that the Om reflects the cosmological beliefs in Hinduism, as the primordial sound associated with the creation of universe from nothing.

Om in scriptures of Hinduism is also called Ekam Aksharam (एकम् अक्षरम्, one syllable).

Jainism

In Jainism, om is considered a condensed form of reference to the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi, by their initials A+A+A+U+M (o3m). The Dravyasamgraha quotes a Prakrit line:

- ओम एकाक्षर पञ्चपरमेष्ठिनामादिपम् तत्कथमिति चेत "अरिहंता असरीरा आयरिया तह उवज्झाया मुणियां"

- "Om" is one syllable made from the initials of the five parameshthis. It has been said: "Arihant, Ashiri, Acharya, Upajjhaya, Muni".

Thus, ओं नमः (oṃ namaḥ) is a short form of the Navkar Mantra.

Buddhism

Esoteric Buddhists place om at the beginning of their Vidya-Sadaksari ("om mani padme hum") as well in as most other mantras and dharanis. Moreover, as a seed syllable (a bija mantra) aum is considered holy in Esoteric Buddhism.

In Buddhist texts of East Asia, om is often written as the Chinese character 唵 (pinyin ǎn) or 嗡 (pinyin wēng).

Sikhism

Main article: Ik Onkar

Ik Onkar, iconically represented as Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: p (help) in the Guru Granth Sahib (although sometimes spelt out in full as ਏਕੰਕਾਰੁ) has been interpreted in a number of ways within Sikhism. It is part of the Mul Mantar in Sikhism, where it contextually means "Onkar is one", an assertion of a monotheistic belief.

The Onkar of Sikhism is related to Om of Hinduism – also called Omkāra – in Hinduism. Some Sikh scholars disagree that Ik Onkar is related to Om. Other Sikh scholars suggest that there is deeper, historical relationship between Ik Onkar to Omkāra, – in Hinduism. as well as to the metaphysical concept of Brahman, particularly as nirguni Brahman – attributeless, formless, eternal Highest Reality.

Modern reception

The Brahmic script om-ligature has become widely recognised in western counterculture since the 1960s. As to its precise graphic form, the Vedic or Indian om is what most Westerners are used to, and the Tibetan alphabet om is less widespread in popular culture. Even Tibetan handicrafts made in India tend to use the Devanagari script om for recognisability.

In music, the symbol is shown on the album cover of the Soulfly's third album, 3.

Usage

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Phonologically, the syllable is /aum/, which is regularly monophthongised to in Sanskrit. It is sometimes also written with pluti, as o3m (ओ३म्), notably by Arya Samaj. When occurring within a Sanskrit utterance, the syllable is subject to the normal rules of sandhi in Sanskrit grammar, however with the additional peculiarity that after preceding a or ā, the au of aum does not form vriddhi (au) but guna (o) per Pāṇini 6.1.95 (i.e. 'om').

The om symbol ![]() (oṃ, encoded in Unicode at U+0950 ॐ) is a ligature of Devanagari ओ (U+0913) + ँ (U+0901).

(oṃ, encoded in Unicode at U+0950 ॐ) is a ligature of Devanagari ओ (U+0913) + ँ (U+0901).

-

Devanagari (Hindi, Nepali, Marathi), Gujarati and Marathi (Modi)

Devanagari (Hindi, Nepali, Marathi), Gujarati and Marathi (Modi)

-

Devanagari as per Arya Samaj

-

Siddham 𑖍𑖼 (U+1158D & U+115BC)

Siddham 𑖍𑖼 (U+1158D & U+115BC)

-

Oriya ଓଁ (U+0B13 & U+0B01)

Oriya ଓଁ (U+0B13 & U+0B01)

Assamese and Bengali ওঁ (U+0993 & U+0981) -

Tibetan ༀ (U+0F00)

Tibetan ༀ (U+0F00)

-

Grantha "oo m"

Grantha "oo m"

-

Tamil ௐ (U+0BD0)

Tamil ௐ (U+0BD0)

-

Kannada ಓಂ (U+0C93 & U+0C82)

Kannada ಓಂ (U+0C93 & U+0C82)

Telugu ఓం (U+0C13 & U+0C02) -

Malayalam ഓം (U+0D13 & U+0D02)

Malayalam ഓം (U+0D13 & U+0D02)

-

Jain symbol

Jain symbol

-

Balinese ᬒᬁ (U+1B12 & U+1B01)

Balinese ᬒᬁ (U+1B12 & U+1B01)

-

Javanese ꦎꦴꦀ (U+A98E & U+A980 & U+A9B4)

Javanese ꦎꦴꦀ (U+A98E & U+A980 & U+A9B4)

-

Chinese 唵 (U+5535)

References

- James Lochtefeld (2002), Om, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N-Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931804, page 482

- Jan Gonda (1963), The Indian Mantra, Oriens, Vol. 16, pages 244-297

- ^ Julius Lipner (2010), Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415456760, pages 66-67

- Krishna Sivaraman (2008), Hindu Spirituality Vedas Through Vedanta, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812543, page 433

- David Leeming (2005), The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195156690, page 54

- Hajime Nakamura, A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy, Part 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120819634, page 318

- ^ Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus (2011), Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism, De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110181593, pages 435-456

- ^ Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus (2011), Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism, De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110181593, page 435

- David White (2011), Yoga in Practice, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691140865, pages 104-111

- Alexander Studholme (2012), The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum: A Study of the Karandavyuha Sutra, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791453902, pages 1-4

- T A Gopinatha Rao (1993), Elements of Hindu Iconography, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120808775, page 248

- Sehdev Kumar (2001), A Thousand Petalled Lotus: Jain Temples of Rajasthan, ISBN 978-8170173489, page 5

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2005), Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0192806017, Chapter 4

- Wendy Doniger (2000), Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam Webster, ISBN 978-0877790440, page 500

- OM Sanskrit English Dictionary, University of Koeln, Germany

- ^ ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १.१ Rigveda, Wikisource;

English Translation:Rigveda Sanhita 1.1.1 HH Wilson (Translator), Trubner & Co, London - Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 207

- John Grimes (1995), Ganapati: The Song of Self, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791424391, pages 78-80 and 201 footnote 34

- Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, Oxford University Press, pages 1-21

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 67-85, 227, 284, 308, 318, 361-366, 468, 600-601, 667, 772

- James Lochtefeld (2002), Pranava, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N-Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931804, page 522

- Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 74-75, 347, 364, 667

- ^ Monier Monier-Williams (1893), Indian Wisdom, Luzac & Co., London, page 17

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 1-3 with footnotes

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 68-70

- Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 171-185

- Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 70-71 with footnotes

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 4-6 with footnotes

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 178-180

- Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 4-19 with footnotes

- Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 171-185

- Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 269-273

- Max Muller (1962), Katha Upanishad, in The Upanishads - Part II, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0486209937, page 8

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 284-286

- Max Muller, Katha Upanishads 1.2.15-1.2.16 Oxford University Press, page 10

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814691, pages 605-637

- ^ Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pp. 391–393

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - Charles Johnston, The Measures of the Eternal - Mandukya Upanishad Theosophical Quarterly, October, 1923, pages 158-162

- ^ Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845193461, page 164

- ^ Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845193461, page 271

- Translator: KT Telang, Editor: Max Muller, The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita at Google Books, Routledge Print, ISBN 978-0700715473, page 120

- Guy Beck (1995), Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812611, page 154

- Paramhans Swami Maheshwarananda, The hidden power in humans, Ibera Verlag, page 15., ISBN 3-85052-197-4

- CK Chapple, W Sargeant (2009), The Bhagavad Gita: Twenty-fifth–Anniversary Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438428420, page 435

- oma ekākṣara pañca-parameṣṭhi-nāmā-dipam tatkathamiti cheta "arihatā asarīrā āyariyā taha uvajjhāyā muṇiyā"

- Wazir Singh, Aspects of Guru Nanak's philosophy (1969), p. 20: "the 'a,' 'u,' and 'm' of aum have also been explained as signifying the three principles of creation, sustenance and annihilation. ... aumkār in relation to existence implies plurality, ... but its substitute Ekonkar definitely implies singularity in spite of the seeming multiplicity of existence. ..."

- ^ Eleanor Nesbitt (2005), Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0192806017, Chapter 4

- Singh, Khushwant (2002). "The Sikhs". In Kitagawa, Joseph Mitsuo (ed.). The religious traditions of Asia: religion, history, and culture. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 114. ISBN 0-7007-1762-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Jean Holm and John Bowker, Worship, Bloomsbury, ISBN , page 67

- Wendy Doniger (2000), Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam Webster, ISBN 978-0877790440, page 500

- Doniger, Wendy (1999). Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 500. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- Jean Holm and John Bowker, Worship, Bloomsbury, ISBN , page 67

- Wendy Doniger (2000), Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam Webster, ISBN 978-0877790440, page 500

- SS Kohli (1993), The Sikh and Sikhism, Atlantic, ISBN 81-71563368, page 39

- Hardip Syan (2014), in The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies (Editors: Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199699308, page 178

- A Mandair (2011), Time and religion-making in modern Sikhism, in Time, History and the Religious Imaginary in South Asia (Editor: Anne Murphy), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415595971, page 188-190

- Messerle, Ulrich. "Graphics of the Sacred Symbol OM".

External links

| Philosophy |

|  | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texts |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Deities |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Practices |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||||||||

| Gods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | |||||

| Branches |

| ||||

| Practices | |||||

| Literature | |||||

| Symbols | |||||

| Ascetics | |||||

| Scholars | |||||

| Community | |||||

| Jainism in |

| ||||

| Jainism and | |||||

| Dynasties and empires | |||||

| Related | |||||

| Lists | |||||

| Navboxes | |||||