This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Shrike (talk | contribs) at 04:43, 15 October 2017 (This Alternative name is significant enough to be included in the lead). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:43, 15 October 2017 by Shrike (talk | contribs) (This Alternative name is significant enough to be included in the lead)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Mausoleum of Abu Huraira / Rabban Gamaliel's Tomb | |

|---|---|

The portico facade in 2010 The portico facade in 2010 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islamic, Jewish |

| Region | Middle East |

| Location | |

| Location | Yavne, Israel |

| |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°52′03″N 34°44′36″E / 31.8675°N 34.7432°E / 31.8675; 34.7432 |

The mausoleum of Abu Hurayra, known to Jews as Rabban Gamaliel's Tomb, is a maqam and synagogue located in HaSanhedrin Park in Yavne, Israel, formerly belonging to the depopulated Palestinian village of Yibna. It has been described by Professor Andrew Petersen, Director of Research in Islamic Archaeology at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, as "one of the finest domed mausoleums in Palestine."

Since the 12th century, it has been known as a tomb of Abu Hurairah, a companion (sahaba) of Muhammad, although most Arabic sources give Medina as his burial place. In 1274, Mamluk Sultan Baybars ordered the construction of the riwaq featuring a tripartite portal and six tiny domes together with a dedicatory inscription, with the site expanded further in 1292 Mamluk Sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil.

After 1948 the shrine became a site of worship by Jews who believe that the spot is the Tomb of Rabban Gamaliel of Yavne. The connection was based on the literature of Medieval Jewish Pilgrims mentioning frequent visits to the tomb.

Architecture

Until 1948 the building stood within a walled compound containing graves (the compound wall and the graves have now disappeared.). There were two inscriptions above the gateway; one in the name of Sultan Baybars dated 673 H. (1274 c.e.) and another dated to 806 H. (1403 C.E.)

A cenotaph is located in centre of the tomb chaimber. The cenotaph is a rectangular structure with four marble corner posts formed as turbans. The four lower courses are made of ashlar blocks, while the upper course is of marble ornamented with niches in gothic style.

Early history

Ali of Herat (d. 1215), followed by Yaqut (d. 1229) and the Marasid al-ittila' (Template:Lang-ar, an abridgement of Yaqut's work by Safi al-Din 'Abd al-Mu'min ibn 'Abd al-Haqq, d.1338), wrote that in Yubna there was a tomb said to be that of Abu Hurairah, the companion (sahaba) of the Prophet. The Marasid also adds that tomb seen here is also said to be that of ʿAbd Allah ibn Abi Sarh, another companion (sahaba) of the Prophet.

A Hebrew travel guide dated between 1266 to 1291 mentioned a tomb of Rabbi Gammliel in Yavne that is used as a Muslim prayer house.

Inscriptions

The first inscription, dated 1274, described how Mamluk Sultan Baybars (reigned 1260–77) ordered the construction of the riwaq. It also refers to the Wali of Ramleh, Khalil ibn Sawir, who was named by the chronicler Ibn al-Furat as being responsible for instigating the famed attempted assassination of Edward I of England in June 1272 in the Ninth Crusade.

The second inscription described further construction ordered in 1292 by Mamluk Sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil (reigned 1290–93).

| Date | Picture | Location | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

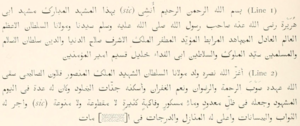

| 673 AH (1274 CE) |

|

Marble slab on door of enclosure | "In the name of the merciful and pitiful God. Gave the order to begin building the blessed porch (rewak), our master, Sultan El-Malek edh-Dhaher, pillar of the world and of religion, Abou'l Fath (the father of conquest) Beibars, co-sharer with the Emir of the Believers, may God exalt his victories! The completion of it took place in the month Rebi' I, in the year 673. Was entrusted with the building Khalil ibn Shawar, wali of Ramlah, whom may God pardon, him, his father and mother, and all the Mussulmans." |

| 692 AH (1292 CE) |

|

Base of doorway and under the lintel | "In the name of the merciful and pitiful God. Began to build this blessed sanctuary (meshhed) of Abu Horeira, may God receive him, companion of the apostle of God, on whom be prayers and salvation, our Lord and our master the very great, learned, and just Sultan, resolute champion and guardian (of Islam), victorious, El-Malek el-Achraf, prosperity of the world and of religion, Sultan of Islam and of the Mussulmans, lord of Kings and Sultans, Abu'l-Feda Khalil, co-sharer with the Emir of the Believers, may God exalt his victory, son of our master the Sultan, hero of the holy war, El-Malek El-Mansur Kelaun es-Salehy, may God water his reign with the rain of his mercy and his grace and the benefits of his indulgence, may he make him to dwell in the gardens of Eternity, may he come to his aid on the day of resurrection, may he make him a place under a wide shade with abundant water and quantities of fruit without stint, may he grant him the reward and the delights he has deserved, may he raise his places and degrees into the..." "Amen ! The building of it was finished in the months of the year 692, and there was entrusted with its building Aydemir the dewadar ("bearer of the inkstand") Ez,-Zeiny (?) may God pardon him, him and his descendants, as also all Mussulmans." |

| 806 AH (1403 CE) |

|

Marble slab | "Renewed this pool, the conduit and the sakia, his Excellency En-Nasery (= Naser ed-din) Mohammed Anar (?), son of Anar (? ?), and his Excellency El-'Alay (= 'Ala ed-din) Yelbogha, possessors (?) of the township of Yebna, may god in his grace and mercy grant to both of them Paradise as a reward. Ordered at the date of the month Rebi' I, in the year 806." |

Modern history

In 1863 Victor Guérin visited, describing the site as a mosque. In 1882, Conder and Kitchener described it: "The mosque of Abu Hureireh is a handsome building under a dome, and contains two inscriptions, the first in the outer court, the second in the wall of the interior."

During the British Mandate of Palestine the porch of the building was used for school rooms. Following 1948, Sephardic Jews worship at the site due to their belief that the tomb is the burial place of Rabbi Gamaliel of Yavne. The identification of the site as Gamaliel's tomb was based on the literature of medieval Jewish pilgrims, who frequently mentioned visits to the site. The claim of previous Jewish origin were based on the argument that the maqam, as many other Muslim sacred tombs, were originally Jewish tombs that were Islamized during the later history of the region. The Israeli Ministry of Religious Services maintains authority of the site since 1948.

Gallery

-

The mausoleum in 1985

The mausoleum in 1985

-

The mausoleum in 2009

The mausoleum in 2009

-

side view

side view

-

side view

side view

-

rear corner

rear corner

-

front corner

front corner

-

dome close up

dome close up

-

interior, with faint inscription showing, and ablaq style masonry.

interior, with faint inscription showing, and ablaq style masonry.

See also

References

- Petersen, 2001, p. 313

- ^ Taragan, 2002, p.31

- ^ Mayer et al., (1950:22) Cited in Petersen, 2001, p. 313

- ^ Bar, 2008, p.9, “Following the War, this Muslim tomb with its typical cupola was converted into a Jewish sacred place, gradually drawing more and more Jewish worshippers. The change in Yavneh had a lot to do with the new local Jewish settlers, immigrants who came primarily from Arab countries to settle in the nearby vacated Arab village of Yubna. These settlers adopted the adjacent tomb and reused it as the tomb of Raban Gamaliel. As in many similar cases throughout the State of Israel, the tradition that connected Jews to Yavneh was not unfounded, and was based mainly on the literature of medieval Jewish pilgrims, who frequently mentioned visits to that place. Jewish claim of ownership over this tomb was based on the argument that it, as well as many other Muslim sacred tombs, were originally Jewish sacred burial places that were Islamized during the later history of the region. During the decades prior to 1948 no visible active or large-scale Jewish pilgrimage to Yavneh was recorded, as was true for most of the sacred places that formed the Jewish sacred space later, during the 1950.”

- Petersen, 2001, p. 316

- Jennifer Speake (12 May 2014). Literature of Travel and Exploration: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 1302–. ISBN 978-1-135-45663-4.

- ^ le Strange, 1890, p.553

- Taragan, 2000, p.70

- Timothy Venning; Peter Frankopan (May 2015). A Chronology of the Crusades. Routledge. pp. 375–. ISBN 978-1-317-49643-4.

- Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, p. 175

- Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, p. 177

- Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, p. 178

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, pp. 442-443

- Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, p. 179

- Guérin, 1869, pp. 56-57

- Wars and sacred space, Doron Bar, 2010, pages 79-85

- Petersen, 2001, p. 315

Bibliography

- Bar, Gideon (2008). "Reconstructing the Past: The Creation of Jewish Sacred Space in the State of Israel, 1948–1967". Israel Studies. 13 (3): 1–21. doi:10.2307/30245829 (inactive 2017-10-14). JSTOR 30245829.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2017 (link) - Clermont-Ganneau, Charles Simon (1896). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873–1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. Vol. 2. London: Palestine Exploration Fund. (Also cited in Petersen, 2001, p. 313)

- Conder, Claude Reignier; Kitchener, H. H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Fischer, M.; Taxel, Itamar (2007). "Ancient Yavneh: Its History and Archaeology". Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv. 34 (2): 204–284.

- Guérin, Victor (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Mayer, L. A.; Pinkerfeld, J.; Yadin, Y. (1950). Some Principal Muslim Religious Buildings in Israel. Jerusalem: Ministry of religious affairs. (Cited in Petersen (2001))

- Meinecke, Michael (1992). Die mamlukische Architektur in Ägypten und Syrien (648/1250 bis 923/1517): Chronologische Liste der mamlukischen Baumassnahmen. Verlag J.J. Augustin. pp. 16, 36, 301. ISBN 978-3-87030-076-0.

- Pedersen, J. (1928). Inscriptiones Semiticae collectionis Ustinowianae. Brgger. pp. 30–32. Cited in Sharon, 2007.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine: Volume I (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Sharon, Moshe (2007). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Addendum. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-15780-4., (pp. 29 -31)

- Strange, le, Guy (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Taragan, Hana (2000). "Politics and Aesthetics: Sultan Baybars and the Abu Hurayra / Rabbi Gamliel Building in Yavneh". In Asher Ovadiah (ed.). Milestones in the Art and Culture of Egypt. Yolanda and David Katz Faculty of the Arts, Tel Aviv University. pp. 117–43.

- Taragan, Hana (2000). "Baybars and the Tomb of Abu Hurayra/Rabban Gamliel in Yavneh / הכוח שבאבן: ביברס וקבר אבו-הרירה/רבן גמליאל ביבנה". Cathedra: for the History of Eretz Israel and Its Yishuv / קתדרה: לתולדות ארץ ישראל ויישובה (97): 65–84. doi:10.2307/23404643 (inactive 2017-10-14). JSTOR 23404643.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2017 (link) - Taragan, Hana, Historical reference in medieval Islamic architecture: Baybar's buildings in Palestine. Bulletin of the Israeli Academic Center in Cairo 25 (2002) 31-34

External site

- Mausoleum of Abu Huraira – archnet.org

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 16: IAA, Wikimedia commons