This is an old revision of this page, as edited by KissL (talk | contribs) at 08:23, 13 October 2006 (rv opinion without citation). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 08:23, 13 October 2006 by KissL (talk | contribs) (rv opinion without citation)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

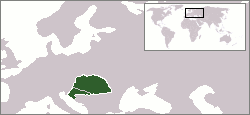

The Kingdom of Hungary (Hungarian: Magyar Királyság, Latin: Regnum Hungariae, German: Königreich Ungarn, Slovak: Uhorské kráľovstvo, Polish: Królestwo Węgier, Croatian and Serbian: Kraljevina Ugarska or Краљевина Угарска, Romanian: Regatul Ungariei) is the name of a kingdom that existed in Central Europe from 1000 to 1918 (until the formation of the Hungarian Democratic Republic). It arose in present-day western Hungary and subsequently spread to remaining present-day Hungary, to Transylvania (in present-day Romania), Slovakia, Carpatho-Ukraine, Vojvodina (in present-day Serbia) and other smaller nearby territories. It existed in personal union with the Kingdom of Croatia from 1102 until 1918 under the name Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen.

Overview

The term "Kingdom of Hungary" is often used to denote this long-lasting multiethnic configuration of territories in order to draw a clear distinction with the modern Hungarian state, which is significantly smaller and more ethnically homogeneous. Prior to and in the 19th century, the term Hungarian in English and other languages often referred to any inhabitant of this state, regardless of his or her ethnicity.

The Latin terms "natio Hungarica" and "Hungarus" referred to all noblemen of the kingdom. A Hungarus-consciousness (loyalty and patriotism above ethnic origins) existed among any inhabitant of this state, however according to István Werbőczy's Tripartitum Natio Hungarica or Hungarus were only the privileged noblemen, subjects of the Holy Crown regardless of ethnicity.

History of the Kingdom of Hungary

Premises

In the 970s - as a pressing result of the changed domestic and foreign affairs - chief prince Géza adopted Christianity, the faith of the victors, and started spreading it in the country. At the same time he started to organize the central power, too. He hardly ever made war against foreign countries during his 25-year-long principality. His peace policy was reinforced by dynastic marriages - which were quite natural at that time - between his children and members of foreign ruling families, to confess the rule of the Magyars in the Pannonian Basin by other european countries.

Géza's efforts to establish a stable state power and guarantee the throne for his son were not really successful, because he had to share some of the country with the other members of the principal family. Prince Koppány also lay his claim for the throne. In the Hungarian succession the theory of seniority - the right of the oldest living brother - prevailed. Koppány also laid claim on the principal's widow, Sharolt. Géza's will, that his first-born son should inherit the throne, contradicted the ancestral right.

In connection with the adoption of Christianity, the question of vital importance was whether Hungary should join the western or the Eastern Orthodox Church. Formerly (around 948) the Hungarian noblemen joined the Byzantine Church. In the autumn of 972 the archbishop of Mainz ,Bruno of Querfurt was sent as bishop of the Hungarians by Pope Silvester II to spread western Christianity among the Hungarians. He christened chief prince Géza and his family also. Géza got the name István when he was christened, his wife, Sharolt, was baptised by a Greek bishop in her early childhood. The decision on the choice was made by current foreign affairs. The last phase of the Hungarian raids was directed against the southeast, and this alienated Byzantine relations. It could have been a warning for the Hungarian principality that the Byzantine emperor abolished the political and religious independence of Bulgaria.

The Hungarian chief prince needed the political, moral and occasional military help of the German empire because of the Byzantine threat. Adopting western Christianity was then both a cultural and a political event for the Hungarians. During Géza's reign the plundering campaigns came to an end also. His efforts, to establish a country, wich is independent of all outer powers was almost reached, when he died. At the same time, the issue of succession to the throne created tension at the court: by ancestral right Koppány should have claimed the throne, but the ruler chose his first-born son to be his successor. The fight in the chief prince's family started after Géza's death, in 997.

Koppány took up arms, and many people joined him in Transdanubia. The rebels represented the old faith and order, the ancient human rights, tribal independence and the pagan belief. His oppose, Vajk

Holy Crown of St. Stephen The first kings of the Kingdom were from the Árpád dynasty. In the early 14th century, this dynasty was replaced by the Angevins, and later the Jagiellonians as well as several non-dynastic rulers, notably Sigismund Luxemburg and Matthias Corvinus.

At the Battle of Mohács in 1526, the Hungarian army was defeated by the forces of the Ottoman Empire, and King Louis II of Hungary was killed. Under the Ottoman attacks the central authority collapsed and a struggle for power broke out. The majority of Hungary's ruling elite elected John Zápolya (10 November 1526). A small minority of aristocrats sided with Ferdinand of Habsburg who was Archduke of Austria and tied to Louis's family by marriage, as King of Hungary; there had been previous agreements that the Habsburgs would take the Hungarian throne if Louis died without heirs, as he did. Ferdinand was elected king by a rump diet in December 1526. On 29 February 1528, King John I of Hungary received the support of the Ottoman Sultan.

A three-sided conflict ensued as Ferdinand moved to assert his rule over as much of the Hungarian kingdom as he could. By 1529 the kingdom had been split into two parts: Habsburg Hungary and "eastern-Kingdom of Hungary". At this time there were no Ottomans on Hungarian territories, except Srem's important castles. By 1541, the fall of Buda marked a further division of Hungary, in three parts and remained so until the end of the 17th century. Although the borders were changing very frequently during this period, the three parts can be identified more or less as follows:

- Present-day Slovakia, north-western Transdanubia, Burgenland, western Croatia, and adjacent territories were under Habsburg rule. This area was referred to as Royal Hungary, and though it nominally remained a separate state, it was administered more or less as part of the Habsburgs' Austrian holdings, to which it was immediately adjacent. This was the continuation of the Kingdom of Hungary.

- The Great Alföld (i.e. most of present-day Hungary, incl. south-eastern Transdanubia and the Banat), partly without north-eastern present-day Hungary, became part of the Ottoman Empire.

- The remaining territory became the newly independent principality of Transylvania, under Zápolya's family. Transylvania was a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire.

After a failed Ottoman invasion of Austria in 1683, the Habsburgs went on the offensive against the Turks; by the end of the 17th century, they had managed to conquer the remainder of the historical Kingdom of Hungary and the principality of Transylvania. At this point, the Royal Hungary terminology was dropped, and the area was once again referred to as the Kingdom of Hungary, although it was still administered as a part of the Habsburg realm. In the 18th century, the Kingdom of Hungary had its own Diet (parliament) and constitution, but the members of the Governor's Council (Helytartótanács, the office of the palatine) were appointed by the Habsburg monarch, and the superior economic institution, the Hungarian Chamber, was directly subordinated to the Court Chamber in Vienna. The official language of the Kingdom of Hungary remained Latin until 1844.

Austria-Hungary

In 1867, following the Ausgleich, the Habsburg Empire became the so-called "dual monarchy" of Austria-Hungary. The historic lands of the Hungarian Crown (the Kingdom of Hungary proper, to which Transylvania was soon incorporated, and Croatia-Slavonia, which maintained a distinct identity and a certain internal autonomy) was granted equal status with the rest of the Habsburg monarchy; the two states comprising Austria-Hungary each had considerable independence, with certain institutions and matters (notably the reigning house, defence, foreign affairs, and finances for common expenditures) remaining joint. This arrangement was to last until 1918, when the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary was divided between Hungary and other new or neighbouring states (Austria, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes) as the Central Powers went down in defeat in World War I. The new borders were fixed in 1920 by the Treaty of Trianon. This is generally seen as the end of the state that is referred to as the Kingdom of Hungary.

After the first World War

It should be noted that Kingdom of Hungary was also the formal name of the Hungarian state that existed approximately on the territory of present-day Hungary from 21 March 1920 until 21 December 1944. This state (which was also commonly referred to as the Hungarian Kingdom) was conceived of as a "kingdom without a king," since there was no consensus on either who should take the throne of Hungary, or what form of government should replace the monarchy. The kingdom was ruled in this period by Miklós Horthy, who had the title of regent. Hungary became a republic on 1 February 1946.

Continuity issue

Magyars tend to emphasise the continuity of the Hungarian state and consider the Kingdom of Hungary one phase of its historical development. The continuity is reflected in national symbols and holidays and in the official commemoration of the millennium of the Hungarian statehood in 2000. According to their point of view, the Kingdom of Hungary was primarily a country of the Hungarian people, not denying the presence and importance of other nationalities.

In contrast, according to the point of view of the other nationalities living on the territory of the former Kingdom of Hungary, such continuity is shared among successor nations because the Kingdom of Hungary was a common state of several peoples since its formation, and therefore it is not identical to modern Hungary, which is a nation state of the Magyars. In the Croatian, Serbian and Slovak languages, there are different names for modern Hungary (hr/sr: Mađarska, sl: Maďarsko) and the Kingdom of Hungary (hr/sr: Ugarska, sl: Uhorsko).

See also

- List of Hungarian rulers

- Nobility in the Kingdom of Hungary

- Administrative divisions of the Kingdom of Hungary

- Comitatus (Kingdom of Hungary)

- History of Hungary

- Croatia in the union with Hungary

- History of Slovakia

- Transylvania