This is an old revision of this page, as edited by PatrickOscar (talk | contribs) at 07:32, 10 June 2019 (→Benefits: Added content). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:32, 10 June 2019 by PatrickOscar (talk | contribs) (→Benefits: Added content)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

Single-winner methodsSingle vote - plurality methods

|

|

Proportional representationParty-list

|

|

Mixed systemsBy results of combination

By mechanism of combination By ballot type |

|

Paradoxes and pathologiesSpoiler effects

Pathological response Paradoxes of majority rule |

Social and collective choiceImpossibility theorems

Positive results |

|

|

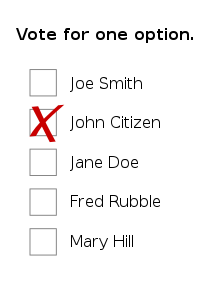

A first-past-the-post (FPTP and sometimes abbreviated to FPP) electoral system is one in which voters indicate on a ballot the candidate of their choice, and the candidate who receives the most votes wins. This is sometimes described as winner takes all. First-past-the-post voting is a plurality voting method. FPTP is a common, but not universal, feature of electoral systems with single-member electoral divisions, and is practised in close to one third of countries. Notable examples include Canada, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States, as well as most of their current or former colonies and protectorates.

Overview

First-past-the-post voting methods can be used for single- and multiple-member electoral divisions. In a single-member election, the candidate with the highest number (but not necessarily a majority) of votes is elected. In a multiple-member election (or multiple-selection ballot), each voter casts (up to) the same number of votes as there are positions to be filled, and those elected are the highest-placed candidates corresponding to that number of positions. For example, if there are three vacancies, then the three candidates with the greatest numbers of votes are elected.

The Electoral Reform Society is a political pressure group based in the United Kingdom that advocates abolishing the first-past-the-post method (FPTP) for all elections. It argues FPTP is "bad for voters, bad for government and bad for democracy". It is the oldest organisation concerned with electoral methods in the world.

In the U.S., all states (except for Maine and Nebraska) and the District of Columbia use a winner-take-all form of simple plurality, first-past-the-post voting, to appoint the electors of the Electoral College; Maine and Nebraska use a variation where the electoral vote of each Congressional district is awarded by first-past-the-post, in addition to the statewide winner taking two votes. In winner-take-all, the presidential candidate gaining the greatest number of votes wins all of the state's available electors, regardless of the number or share of votes won, or the difference separating the leading candidate and the first runner-up.

The multiple-round election (runoff) voting method uses first-past-the-post voting method in each of two rounds. The first round determines which candidates will progress to the second and final round.

Illustration

Under a first-past-the-post voting method, the highest polling candidate is elected. In this real-life illustration from 2011, Tony Tan obtained a greater number of votes than any of the other candidates. Therefore, he was declared the winner, although the second-placed candidate had an inferior margin of only 0.35% and a majority of voters (64.8%) did not vote for the declared winner: Template:Singaporean presidential election, 2011

Effects

The effect of a system based on plurality voting is that the larger parties, and parties with geographically concentrated support, gain a disproportionately large share of seats, while smaller parties with more evenly distributed support are left with a disproportionately small share. It is more likely that a single party will hold a majority of legislative seats. In the United Kingdom, 18 of the 23 general elections since 1922 have produced a single-party majority government; for example, the 2005 general election results were as follows:

| Seats Parties with over one seat, for Great Britain only |

Seats % | Votes % | Votes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour Party | 355 | 56.5 | 36.1 | 9,552,436 |

| Conservative Party | 198 | 31.5 | 33.2 | 8,782,192 |

| Liberal Democrats | 62 | 9.9 | 22.6 | 5,985,454 |

| Scottish National Party | 6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 412,267 |

| Plaid Cymru | 3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 174,838 |

| Others | 4 | 0.6 | 5.7 | 1,523,716 |

| 628 | 26,430,908 | |||

In this example, Labour took a majority of the seats with only 36% of the vote. The largest two parties took 69% of the vote and 88% of the seats. In contrast, the Liberal Democrats took more than 20% of the vote but only about 10% of the seats.

Another example would be the UK General Election held on 7 May 2015:

| Party | Votes | Seats | Votes per Seat | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative Party | 11,334,920 (36.8%) | 331 (50.9%) | 331 / 650 | 34,244 | ||

| Labour Party | 9,344,328 (30.4%) | 232 (35.7%) | 232 / 650 | 40,277 | ||

| UK Independence Party | 3,881,129 (12.6%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 / 650 | 3,881,129 | ||

| Liberal Democrats | 2,415,888 (7.9%) | 8 (1.2%) | 8 / 650 | 301,986 | ||

| Scottish National Party | 1,454,436 (4.7%) | 56 (8.6%) | 56 / 650 | 25,972 | ||

| Green Party | 1,154,562 (3.8%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 / 650 | 1,154,562 | ||

| Democratic Unionist Party | 184,260 (0.6%) | 8 (1.2%) | 8 / 650 | 23,033 | ||

| Plaid Cymru | 181,694(0.6%) | 3 (0.5%) | 3 / 650 | 60,565 | ||

| Sinn Féin | 176,232 (0.6%) | 4 (0.6%) | 4 / 650 | 44,058 | ||

| Ulster Unionist Party | 114,935 (0.4%) | 2 (0.3%) | 2 / 650 | 57,468 | ||

| Social Democratic & Labour Party | 99,809 (0.3%) | 3 (0.5%) | 3 / 650 | 33,270 | ||

Here, the Conservatives took 51% of the seats with only 37% of the vote. Of the smaller parties, the SNP received a greater share of seats than votes, whereas UKIP and the Liberal Democrats gained very little representation compared to the share of the vote they received.

These examples suggest an inbuilt bias to Labour. With a lower percentage of votes in 2005 than the Conservatives in 2015, they received 30 odd more seats, enough to form a majority. A more perverse outcome was that in 1987 where Labour received 30% and the Liberal Social Democrat Alliance 22% of the votes but this did not amount to a majority of seats. Even odder Labour received 10 times as many seats as the Alliance. The Alliance lost out because parties with less than 30% are seriously under-represented. Labour’s advantage over the Tories is because the Tory vote is more concentrated in safe seats which they win big, meaning their votes are wasted and which means Labour votes are more optimally distributed and they win more marginal seats.

The Singapore example shows the unrepresentativeness of FPTP more starkly. The winning candidate was not supported by almost 70% of voters.

Benefits

The benefits of FPTP are that its concept is easy to understand, and ballots can more easily be counted and processed than in preferential voting systems.

First past the post's tendency to produce majority rule allows a government to pursue a consistent strategy for its term in office and to make decisions that may have socially beneficial outcomes, but be unpopular.

Tony Blair, defending FPTP, argued that other systems give small parties the balance of power, and influence disproportionate to their votes.

Allowing people into the UK parliament who did not finish first in their constituency was described by David Cameron as creating a "Parliament full of second-choices who no one really wanted but didn't really object to either." Winston Churchill criticised the electoral outcomes of the alternative vote as "determined by the most worthless votes given for the most worthless candidates."

Supporters also argue that electoral systems using proportional representation (PR) often enable smaller parties to become decisive in Parliament, thus gaining a power of leverage against the Government. FPTP generally reduces this likelihood, except where parties have a strong regional basis. Although two of the last U.K. elections have produced hung Parliaments where the leading party relies on another party for a Parliamentary majority, FPTP has the advantage of usually producing a clear outcome. The alternative system of Proportional Representation (PR) rarely produces an overall winner and leads to post-election negotiations to construct a Parliamentary majority. This often leads to major compromises in positions. It can also give small parties inordinate power in that the numbers may allow a small party to determine which of two bigger parties or alliances can take power and exert a disproportionate influence on the Government.

Criticisms

Tactical voting

To a greater extent than many others, the first-past-the-post method encourages tactical voting. Voters have an incentive to vote for a candidate who they predict is more likely to win, in preference to their preferred candidate who may be unlikely to win and for whom a vote could be considered as wasted.

The position is sometimes summarised, in an extreme form, as "all votes for anyone other than the runner-up are votes for the winner." This is because votes for these other candidates deny potential support from the second-placed candidate, who might otherwise have won. Following the extremely close 2000 U.S. presidential election, some supporters of Democratic candidate Al Gore believed that one reason he lost to Republican George W. Bush is because a portion of the electorate (2.7%) voted for Ralph Nader of the Green Party, and exit polls indicated that more of them would have preferred Gore (45%) to Bush (27%). This election was ultimately determined by the results from Florida, where Bush prevailed over Gore by a margin of only 537 votes (0.009%), which was far exceeded by the 97488 (1.635%) votes for Nader.

In Puerto Rico, there has been a tendency for Independentista voters to support Populares candidates. This phenomenon is responsible for some Popular victories, even though the Estadistas have the most voters on the island, and is so widely recognised that Puerto Ricans sometimes call the Independentistas who vote for the Populares "melons", because that fruit is green on the outside but red on the inside (in reference to the party colors).

Because voters have to predict in advance who the top two candidates will be, results can be significantly distorted:

- Some voters will vote based on their view of how others will vote as well, changing their originally intended vote;

- Substantial power is given to the media, because some voters will believe its assertions as to who the leading contenders are likely to be. Even voters who distrust the media will know that others do believe the media, and therefore those candidates who receive the most media attention will probably be the most popular;

- A new candidate with no track record, who might otherwise be supported by the majority of voters, may be considered unlikely to be one of the top two, and thus lose votes to tactical voting;

- The method may promote votes against as opposed to votes for. For example, in the UK (and only in the Great Britain region), entire campaigns have been organised with the aim of voting against the Conservative Party by voting Labour, Liberal Democrat in England and Wales, and since 2015 the SNP in Scotland, depending on which is seen as best placed to win in each locality. Such behaviour is difficult to measure objectively.

Proponents of other voting methods in single-member districts argue that these would reduce the need for tactical voting and reduce the spoiler effect. Examples include preferential voting systems, such as instant runoff voting, as well as the two-round system of runoffs and less tested methods such as approval voting and Condorcet methods.

Effect on political parties

Duverger's law is an idea in political science which says that constituencies that use first-past-the-post methods will lead to two-party systems, given enough time. Economist Jeffrey Sachs explains:

The main reason for America's majoritarian character is the electoral system for Congress. Members of Congress are elected in single-member districts according to the "first-past-the-post" (FPTP) principle, meaning that the candidate with the plurality of votes is the winner of the congressional seat. The losing party or parties win no representation at all. The first-past-the-post election tends to produce a small number of major parties, perhaps just two, a principle known in political science as Duverger's Law. Smaller parties are trampled in first-past-the-post elections.

— from Sachs's The Price of Civilization, 2011

However, most countries with first-past-the-post elections have multiparty legislatures, the United States being the major exception. There is a counter-force to Duverger's Law, that while on the national level a plurality system may encourage two parties, in the individual constituencies supermajorities will lead to the vote fracturing.

Wasted votes

Wasted votes are seen as those cast for losing candidates, and for winning candidates in excess of the number required for victory. For example, in the UK general election of 2005, 52% of votes were cast for losing candidates and 18% were excess votes – a total of 70% 'wasted' votes. On this basis a large majority of votes may play no part in determining the outcome. This winner-takes-all system may be one of the reasons why "voter participation tends to be lower in countries with FPTP than elsewhere."

Gerrymandering

Main article: GerrymanderingBecause FPTP permits many wasted votes, an election under FPTP is more easily gerrymandered. Through gerrymandering, electoral areas are designed deliberately to unfairly increase the number of seats won by one party, by redrawing the map such that one party has a small number of districts in which it has an overwhelming majority of votes, and a large number of districts where it is at a smaller disadvantage. This can be seen in the House of Representatives districts in which one party has such a huge majority that no more than 10% of electoral races are competitive and the biggest challenge to an incumbent comes in the party primary to select the candidate. It can also be seen in the US Senate where at any election only one of the two Senate seats is up for grabs. This means Democrats hold both seats in California and New York and Republican votes in those states are wasted. The reverse applies in States like Texas. Gerrymandering by a party in power can be used to create districts where thatparty can win a seat where previously it could not by herding votes for the opposition party into districts where they win big, thus wasting their votes.

Manipulation charges

The presence of spoilers often gives rise to suspicions that manipulation of the slate has taken place. A spoiler may have received incentives to run. A spoiler may also drop out at the last moment, inducing charges that such an act was intended from the beginning.

Smaller parties may reduce the success of the largest similar party

Under first-past-the-post, a small party may draw votes away from a larger party that it is most similar to, and therefore give an advantage to one it is less similar to.

Safe seats

First-past-the-post within geographical areas tends to deliver (particularly to larger parties) a significant number of safe seats, where a representative is sheltered from any but the most dramatic change in voting behaviour. In the UK, the Electoral Reform Society estimates that more than half the seats can be considered as safe. It has been claimed that MPs involved in the 2009 expenses scandal were significantly more likely to hold a safe seat.

However, other voting systems, notably the party-list system, can also create politicians who are relatively immune from electoral pressure. The problem with the party list arises when the parties seats, reflecting its share of the popular vote are filled by appointment from the top of a list drawn up by the party and May include individuals who themselves would be unelectable in popular votes. To the extent the unpopular politician coheres to the party policy this is not a problem.

Distorted geographical representation

The winner-takes-all nature of FPTP leads to distorted patterns of representation, since party support is commonly correlated with geography. For example, in the UK the Conservative Party represents most of the rural seats, and most of the south of the country, and the Labour Party most of the cities, and most of the north. This means that even popular parties can find themselves without elected politicians in significant parts of the country, leaving their supporters (who may nevertheless be a significant minority) unrepresented. Note in the chart above from the 2015 UK election that the UK Independence Party came in third in terms of sheer number of voters, but only gained one seat in Parliament despite having broad national support since its vote was not concentrated in local election districts.

Impact on party policy and campaigning

It has been suggested that the distortions in geographical representation provide incentives for parties to ignore the interests of areas in which they are too weak to stand much chance of gaining representation, leading to governments that do not govern in the national interest. Further, during election campaigns the campaigning activity of parties tends to focus on marginal seats where there is a prospect of a change in representation, leaving safer areas excluded from participation in an active campaign. Political parties operate by targeting districts, directing their activists and policy proposals toward those areas considered to be marginal, where each additional vote has more value.

Voting method criteria

Scholars rate voting methods using mathematically derived voting method criteria, which describe desirable features of a method. No ranked preference method can meet all of the criteria, because some of them are mutually exclusive, as shown by results such as Arrow's impossibility theorem and the Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem.

Majority criterion

![]() Y The majority criterion states that "if one candidate is preferred by a majority (more than 50%) of voters, then that candidate must win". First-past-the-post meets this criterion (though not the converse: a candidate does not need 50% of the votes in order to win). Although the criterion is met for each constituency vote, it is not met when adding up the total votes for a winning party in a parliament.

Y The majority criterion states that "if one candidate is preferred by a majority (more than 50%) of voters, then that candidate must win". First-past-the-post meets this criterion (though not the converse: a candidate does not need 50% of the votes in order to win). Although the criterion is met for each constituency vote, it is not met when adding up the total votes for a winning party in a parliament.

Condorcet winner criterion

![]() N The Condorcet winner criterion states that "if a candidate would win a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must win the overall election". First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

N The Condorcet winner criterion states that "if a candidate would win a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must win the overall election". First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

Condorcet loser criterion

![]() N The Condorcet loser criterion states that "if a candidate would lose a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must not win the overall election". First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

N The Condorcet loser criterion states that "if a candidate would lose a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must not win the overall election". First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

Independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion

![]() N The independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if a candidate who cannot win decides to run." First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

N The independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if a candidate who cannot win decides to run." First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

Independence of clones criterion

![]() N The independence of clones criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if an identical candidate who is equally-preferred decides to run." First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

N The independence of clones criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if an identical candidate who is equally-preferred decides to run." First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

List of current FPTP countries

The following is a list of countries currently following the first-past-the-post voting system for their national legislatures.

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Azerbaijan

- Bahamas

- Barbados

- Bangladesh

- Belize

- Bermuda (United Kingdom)

- Bhutan

- Botswana

- Brazil (Federal Senate)

- Canada

- Cayman Islands (United Kingdom)

- Cote d'Ivoire

- Cook Islands (New Zealand)

- Dominica

- Eritrea

- Eswatini

- Ethiopia

- Gabon

- Gambia

- Ghana

- Grenada

- India

- Indonesia (Regional Representative Council)

- Jamaica

- Kenya

- Kuwait

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Liberia

- Marshall Islands

- Maldives

- Malawi

- Malaysia

- Mauritius

- Micronesia

- Myanmar (Burma)

- Nigeria

- Niue

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Palau

- Philippines

- Poland (Senate)

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Samoa

- Seychelles

- Singapore

- Sierra Leone

- Solomon Islands

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Tonga

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Tuvalu

- Uganda

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Virgin Islands (United Kingdom and United States)

- Yemen

- Zambia

List of former FPTP countries

| This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. (July 2016) |

- Argentina (The Chamber of Deputies uses Party list PR. Only twice used FPTP, first between 1902 and 1905 only used in the elections of 1904, and the second time between 1951 and 1957 only used in the elections of 1951 and 1954.)

- Australia (replaced by IRV in 1918, and for the Australian Senate with STV in 1948)

- Belgium (adopted in 1831, replaced by Party list PR in 1899)

- Cyprus (replaced by proportional representation in 1981)

- Denmark (replaced by proportional representation in 1920)

- Hong Kong (adopted in 1995, replaced by List PR in 1998)

- Lebanon (replaced by proportional representation in June 2017)

- Lesotho (replaced by MMP Party list in 2002)

- Malta (replaced by STV in 1921)

- Nepal (replaced by a mix of Party list and FPTP)

- Netherlands (replaced by Party list PR in 1917)

- New Zealand (replaced by MMP in 1996)

- Papua New Guinea (replaced by IRV in 2002)

- South Africa (replaced by Party list PR in 1996)

- Portugal

See also

- Cube rule

- Deviation from proportionality

- Plurality-at-large voting

- Approval voting

- Single non-transferable vote

- Single transferable vote

References

- Affairs, The Department of Internal. "More about FPP". www.dia.govt.nz. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "U. S. Electoral College: Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Andy Williams (1998). UK Government & Politics. Heinemann. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-0-435-33158-0.

- P. Dorey (17 June 2008). The Labour Party and Constitutional Reform: A History of Constitutional Conservatism. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 400–. ISBN 978-0-230-59415-9.

- David Cameron. "Why keeping first past the post is vital for democracy." Daily Telegraph. 30 Apr 2011

- Larry Johnston (13 December 2011). Politics: An Introduction to the Modern Democratic State. University of Toronto Press. pp. 231–. ISBN 978-1-4426-0533-6.

- Ilan, Shahar. "about blackmail power of Israeli small parties under PR". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- "Dr.Mihaela Macavei, University of Alba Iulia" (PDF). Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- Rosenbaum, David E. (24 February 2004). "THE 2004 CAMPAIGN: THE INDEPENDENT; Relax, Nader Advises Alarmed Democrats, but the 2000 Math Counsels Otherwise". The New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- Sachs, Jeffrey (2011). The Price of Civilization. New York: Random House. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4000-6841-8.

- Dunleavy, Patrick (18 June 2012). "Duverger's Law is a dead parrot. Outside the USA, first-past-the-post voting has no tendency at all to produce two party politics". blogs.lse.ac.uk.

- Dunleavy, Patrick; Diwakar, Rekha (2013). "Analysing multiparty competition in plurality rule elections" (PDF). Party Politics. 19 (6): 855–886. doi:10.1177/1354068811411026.

- Dickson, Eric S.; Scheve, Kenneth (2010). "Social Identity, Electoral Institutions and the Number of Candidates". British Journal of Political Science. 40 (2): 349–375. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.75.155. doi:10.1017/s0007123409990354. JSTOR 40649446.

- Drogus, Carol Ann (2008). Introducing comparative politics: concepts and cases in context. CQ Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-87289-343-6.

- "General Election 2010: Safe and marginal seats". www.theguardian.com. Guardian Newspapers. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Wickham, Alex. ""Safe seats" almost guarantee corruption". www.thecommentator.com. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "FactCheck: expenses and safe seats". www.channel4.com. Channel 4. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "First Past the Post". www.conservativeelectoralreform.org. Conservative Action for Electoral Reform. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "First Past the Post is a 'broken voting system'". www.ippr.org. Institute for Public Policy Research. 4 January 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Terry, Chris (28 August 2013). "In Britain's first past the post electoral system, some votes are worth 22 times more than others". www.democraticaudit.com. London School of Economics. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Galvin, Ray. "What is a marginal seat?". www.justsolutions.eu. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- David Austen-Smith and Jeffrey Banks, "Monotonicity in Electoral Systems", American Political Science Review, Vol 85, No 2 (Jun. 1991)

- Single-winner Voting Method Comparison Chart Archived 28 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine "Majority Favorite Criterion: If a majority (more than 50%) of voters consider candidate A to be the best choice, then A should win."

- ^ Felsenthal, Dan S. (2010) Review of paradoxes afflicting various voting procedures where one out of m candidates (m ≥ 2) must be elected. In: Assessing Alternative Voting Procedures, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

- "Countries using FPTP electoral system for national legislature". idea.int. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Electoral Systems". ACE Electoral Knowledge Network. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Milia, Juan Guillermo (2015). El Voto. Expresión del poder ciudadano. Buenos Aires: Editorial Dunken. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-987-02-8472-7.

- "Law 14,032". Sistema Argentino de Información Jurídica.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Kiesstelsel. §1.1 Federale verkiezingen". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Bhuwan Chandra Upreti (2010). Nepal: Transition to Democratic Republican State : 2008 Constituent Assembly. Gyan Publishing House. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-81-7835-774-4.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Kiesstelsel. §1.1 Geschiedenis". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- "PNG voting system praised by new MP". ABC. 12 December 2003. Archived from the original on 4 January 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

External links

- A handbook of Electoral System Design from International IDEA

- ACE Project: What is the electoral system for Chamber 1 of the national legislature?

- ACE Project: First Past The Post – Detailed explanation of first-past-the-post voting

- ACE Project: Experiments with moving away from FPTP in the UK

- ACE Project: Electing a President using FPTP

- ACE Project: FPTP on a grand scale in India

- The Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform says the new proportional electoral system it proposes for British Columbia will improve the practice of democracy in the province.

- Vote No to Proportional Representation BC

- Fact Sheets on Electoral Systems provided to members of the Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform, British Columbia.

- The Problem With First-Past-The-Post Electing (data from UK general election 2005)

- The Problems with First Past the Post Voting Explained (video) on YouTube

- The fatal flaws of First-past-the-post electoral systems

| 2011 United Kingdom Alternative Vote referendum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | |||||||

| Referendum question | "At present, the UK uses the “first past the post” system to elect MPs to the House of Commons. Should the “alternative vote” system be used instead?" | ||||||

| Legislation | |||||||

| Parties |

| ||||||

| Advocacy groups |

| ||||||

| Print media |

| ||||||

| Politics Portal | |||||||

| Parliament of New Zealand | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components |

|   | |||

| Parliamentary officers |

| ||||

| Members |

| ||||

| Procedure | |||||

| Elections |

| ||||

| Locations |

| ||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||

Categories: