This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Snoopy12346 (talk | contribs) at 15:41, 16 September 2020 (→History). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:41, 16 September 2020 by Snoopy12346 (talk | contribs) (→History)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Native Americans/First Nations peoples of the Great Plains of North America.| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Plains Indians" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

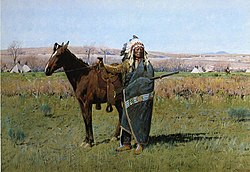

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Great Plains and the Canadian Prairies (also called the Interior Plains) in North America. While hunting-farming cultures have lived on the Great Plains for centuries prior to European contact, the region is known for the horse cultures that flourished from the 17th century through the late 19th century. Their historic nomadism and armed resistance to domination by the government and military forces of Canada and the United States have made the Plains Indian culture groups an archetype in literature and art for American Indians everywhere.

Plains Indians are usually divided into two broad classifications which overlap to some degree. The first group became a fully nomadic horse culture during the 18th and 19th centuries, following the vast herds of buffalo, although some tribes occasionally engaged in agriculture. These include the Blackfoot, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Gros Ventre, Kiowa, Lakota, Lipan, Plains Apache (or Kiowa Apache), Plains Cree, Plains Ojibwe, Sarsi, Nakoda (Stoney), and Tonkawa. The second group of Plains Indians were sedentary and semi-sedentary, and, in addition to hunting buffalo, they lived in villages, raised crops, and actively traded with other tribes. These include the Arikara, Hidatsa, Iowa, Kaw (or Kansa), Kitsai, Mandan, Missouria, Omaha, Osage, Otoe, Pawnee, Ponca, Quapaw, Wichita, and the Santee Dakota, Yanktonai and Yankton Dakota.

my mom hates me please help :(

Material culture

Agriculture and plant foods

The semi-sedentary, village-dwelling Plains Indians depended upon agriculture for a large share of their livelihood, particularly those who lived in the eastern parts of the Great Plains which had more precipitation than the western side. Corn was the dominant crop, followed by squash and beans. Tobacco, sunflower, plums and other wild plants were also cultivated or gathered in the wild. Among the wild crops gathered the most important were probably berries to flavor pemmican and the Prairie Turnip.

The first indisputable evidence of maize cultivation on the Great Plains is about 900 AD. The earliest farmers, the Southern Plains villagers were probably Caddoan speakers, the ancestors of the Wichita, Pawnee, and Arikara of today. Plains farmers developed short-season and drought resistant varieties of food plants. They did not use irrigation but were adept at water harvesting and siting their fields to receive the maximum benefit of limited rainfall. The Hidatsa and Mandan of North Dakota cultivated maize at the northern limit of its range.

The farming tribes also hunted buffalo, deer, elk, and other game. Typically, on the southern Plains, they planted crops in the spring, left their permanent villages to hunt buffalo in the summer, returned to harvest crops in the fall, and left again to hunt buffalo in the winter. The farming Indians also traded corn to the nomadic tribes for dried buffalo meat.

With the arrival of the horse, some tribes, such as the Lakota and Cheyenne, gave up agriculture to become full-time, buffalo-hunting nomads.

Hunting

Although people of the Plains hunted other animals, such as elk or antelope, buffalo was the primary game food source. Before horses were introduced, hunting was a more complicated process. Hunters would surround the bison, and then try to herd them off cliffs or into confined places where they could be more easily killed. The Plains Indians constructed a v-shaped funnel, about a mile long, made of fallen trees or rocks. Sometimes bison could be lured into a trap by a person covering himself with a bison skin and imitating the call of the animals.

Before their adoption of guns, the Plains Indians hunted with spears, bows, and various forms of clubs. The use of horses by the Plains Indians made hunting (and warfare) much easier. With horses, the Plains Indians had the means and speed to stampede or overtake the bison. The Plains Indians reduced the length of their bows to three feet to accommodate their use on horseback. They continued to use bows and arrows after the introduction of firearms, because guns took too long to reload and were too heavy. In the summer, many tribes gathered for hunting in one place. The main hunting seasons were fall, summer, and spring. In winter, adverse weather such as snow and blizzards made it more difficult to locate and hunt bison.

Clothing

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2013) |

Hides, with or without fur, provided material for much clothing. Most of the clothing consisted of the hides of buffalo and deer, as well as numerous species of birds and other small game. Plains moccasins tended to be constructed with soft braintanned hide on the vamps and tough rawhide for the soles. Men's moccasins tended to have flaps around the ankles, while women's had high tops, which could be pulled up in the winter and rolled down in the summer. Honored warriors and leaders earn the right to wear war bonnets, headdresses with feathers, often of golden or bald eagles.

Society and Culture

Religion

While there are some similarities among linguistic and regional groups, different tribes have their own cosmologies and world views. Some of these are animist in nature, with aspects of polytheism, while others tend more towards monotheism or panentheism. Prayer is a regular part of daily life, for regular individuals as well as spiritual leaders, alone and as part of group ceremonies. One of the most important gatherings for many of the Plains tribes is the yearly Sun Dance, an elaborate spiritual ceremony that involves personal sacrifice, multiple days of fasting and prayer for the good of loved ones and the benefit of the entire community.

Certain people are considered to be wakan (Lakota: "holy"), and go through many years of training to become medicine men or women, entrusted with spiritual leadership roles in the community. The buffalo and eagle are particularly sacred to many of the Plains peoples, and may be represented in iconography, or parts used in regalia. In Plains cosmology, certain items may possess spiritual power, particularly medicine bundles which are only entrusted to prominent religious figures of a tribe, and passed down from keeper to keeper in each succeeding generation.

Gender roles

Historically, Plains Indian women had distinctly defined gender roles that were different from, but complementary to, men's roles. They typically owned the family's home and the majority of its contents. In traditional culture, women tanned hides, tended crops, gathered wild foods, prepared food, made clothing, and took down and erected the family's tepees. In the present day, these customs are still observed when lodges are set up for ceremonial use, such as at pow wows. Historically, Plains women were not as engaged in public political life as were the women in the coastal tribes. However, they still participated in an advisory role and through the women's societies.

In contemporary Plains cultures, traditionalists work to preserve the knowledge of these traditions of everyday life and the values attached to them.

Plains women in general have historically had the right to divorce and keep custody of their children. Because women own the home, an unkind husband can find himself homeless. A historical example of a Plains woman divorcing is Making Out Road, a Cheyenne woman, who in 1841 married non-Native frontiersman Kit Carson. The marriage was turbulent and formally ended when Making Out Road threw Carson and his belongings out of her tepee (in the traditional manner of announcing a divorce). She later went on to marry, and divorce, several additional men, both European-American and Indian.

Warfare

The earliest Spanish explorers in the 16th century did not find the Plains Indians especially warlike. The Wichita in Kansas and Oklahoma lived in dispersed settlements with no defensive works. The Spanish initially had friendly contacts with the Apache (Querechos) in the Texas Panhandle.

Three factors led to a growing importance of warfare in Plains Indian culture. First, was the Spanish colonization of New Mexico which stimulated raids and counter-raids by Spaniards and Indians for goods and slaves. Second, was the contact of the Indians with French fur traders which increased rivalry among Indian tribes to control trade and trade routes. Third, was the acquisition of the horse and the greater mobility it afforded the Plains Indians. What evolved among the Plains Indians from the 17th to the late 19th century was warfare as both a means of livelihood and a sport. Young men gained both prestige and plunder by fighting as warriors, and this individualistic style of warfare ensured that success in individual combat and capturing trophies of war were highly esteemed

The Plains Indians raided each other, the Spanish colonies, and, increasingly, the encroaching frontier of the Anglos for horses, and other property. They acquired guns and other European goods primarily by trade. Their principal trading products were buffalo hides and beaver pelts. The most renowned of all the Plains Indians as warriors were the Comanche whom The Economist noted in 2010: "They could loose a flock of arrows while hanging off the side of a galloping horse, using the animal as protection against return fire. The sight amazed and terrified their white (and Indian) adversaries." The American historian S. C. Gwynne called the Comanche "the greatest light cavalry on the earth" in the 19th century whose raids in Texas terrified the American settlers.

Although they could be tenacious in defense, Plains Indians warriors took the offensive mostly for material gain and individual prestige. The highest military honors were for "counting coup"—touching a live enemy. Battles between Indians often consisted of opposing warriors demonstrating their bravery rather than attempting to achieve concrete military objectives. The emphasis was on ambush and hit and run actions rather than closing with an enemy. Success was often counted by the number of horses or property obtained in the raid. Casualties were usually light. "Indians consider it foolhardiness to make an attack where it is certain some of them will be killed." Given their smaller numbers, the loss of even a few men in battle could be catastrophic for a band, and notably at the battles of Adobe Walls in Texas in 1874 and Rosebud in Montana in 1876, the Indians broke off battle despite the fact that they were winning as the casualties were not considered worth a victory. The most famous victory ever won by the Plains Indians over the United States, the Battle of Little Bighorn, in 1876, was won by the Lakota (Sioux) and Cheyenne fighting on the defensive. Decisions whatever to fight or not were based on a cost-benefit ratio; even the loss of one warrior was not considered to be worth taking a few scalps, but if a herd of horses could be obtained, the loss of a warrior or two was considered acceptable. Generally speaking, given the small sizes of the bands and the vast population of the United States, the Plains Indians sought to avoid casualties in battle, and would avoid fighting if it meant losses.

Due to their mobility, endurance, horsemanship, and knowledge of the vast plains that were their domain, the Plains Indians were often victors in their battles against the U.S. army in the American era from 1803 to about 1890. However, although Indians won many battles, they could not undertake lengthy campaigns. Indian armies could only be assembled for brief periods of time as warriors also had to hunt for food for their families. The exception to that was raids into Mexico by the Comanche and their allies in which the raiders often subsisted for months off the riches of Mexican haciendas and settlements. The basic weapon of the Indian warrior was the short, stout bow, designed for use on horseback and deadly, but only at short range. Guns were usually in short supply and ammunition scarce for Native warriors. The U.S. government through the Indian Agency would sell the Plains Indians for hunting, but unlicensed traders would exchange guns for buffalo hides. The shortages of ammunition together with the lack of training to handle firearms meant the preferred weapon was the bow and arrow.

Research

The people of the Great Plains have been found to be the tallest people in the world during the late 19th century, based on 21st century analysis of data (originally) collected by Franz Boas for the World Columbian Exposition. This information is significant to anthropometric historians, who usually equate the height of populations with their overall health and standard of living.

Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies

Further information: Classification of indigenous peoples of the AmericasIndigenous peoples of the Great Plains are often separated into Northern and Southern Plains tribes.

- Anishinaabe (Anishinape, Anicinape, Neshnabé, Nishnaabe) (see also Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands)

- Saulteaux (Nakawē), Manitoba, Minnesota and Ontario; later Alberta, British Columbia, Montana, Saskatchewan

- Apache (see also Southwest)

- Lipan Apache, New Mexico, Texas

- Plains Apache (Kiowa Apache), Oklahoma

- Querecho Apache, Texas

- Arapaho (Arapahoe), formerly Colorado, currently Oklahoma and Wyoming

- Arikara (Arikaree, Arikari, Ree), North Dakota

- Atsina (Gros Ventre), Montana

- Blackfoot

- Kainai Nation (Káínaa, Blood), Alberta

- Northern Peigan (Aapátohsipikáni), Alberta

- Blackfeet, Southern Piegan (Aamsskáápipikani), Montana

- Siksika (Siksikáwa), Alberta

- Cheyenne, Montana, Oklahoma

- Suhtai, Montana, Oklahoma

- Comanche, Oklahoma, Texas

- Plains Cree, Montana, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Manitoba

- Crow (Absaroka, Apsáalooke), Montana

- Escanjaques, Oklahoma

- Hidatsa, North Dakota

- Iowa (Ioway), Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma

- Kaw (Kansa, Kanza), Kansas, Oklahoma

- Kiowa, Oklahoma

- Mandan, North Dakota

- Métis people (Canada), North Dakota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta

- Missouri (Missouria), Oklahoma

- Omaha, Nebraska

- Osage, Oklahoma, formerly Arkansas, Missouri

- Otoe (Oto), Oklahoma, formerly Missouri

- Pawnee, Oklahoma

- Chaui, Oklahoma

- Kitkehakhi, Oklahoma

- Pitahawirata, Oklahoma

- Skidi, Oklahoma

- Ponca, Nebraska, Oklahoma

- Quapaw, formerly Arkansas, Oklahoma

- Sioux (Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, Seven Council Fires)

- Dakota, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan

- Bdewékhaŋthuŋwaŋ (Spirit Lake Village)

- Sisíthuŋwaŋ (Swamp/lake/fish Scale Village)

- Waȟpékhute (Leaf Archers)

- Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ (Leaf Village)

- Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ (End Village)

- Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna (Little End Village)

- Lakota (Thítȟuŋwaŋ, Dwellers on the Prairies), Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Saskatchewan

- Nakoda (Stoney), Alberta

- Nakota, Assiniboine (Assiniboin), Montana, Saskatchewan

- Dakota, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan

- Teyas, Texas

- Tonkawa, Oklahoma

- Tsuu T'ina, (Sarcee, Sarsi, Tsuut'ina), Alberta

- Wichita and Affiliated Tribes (Kitikiti'sh), Oklahoma, formerly Texas and Kansas

See also

- Comanche-Mexico Wars

- Plains Standard Sign Language

- Plains hide painting

- Hair drop, Plains men's adornment

- Native American tribes in Nebraska

- Buffalo jump

- Powwow

- Southern Plains villagers

Notes

- Drass, Richard R. (Feb 2008). "Corn, Beans and Bison: Cultivated Plants and Changing Economies of the Late Prehistoric Villagers on the Plains of Oklahoma and Northwest Texas". Plains Anthropologist. 53 (205): 12. doi:10.1179/pan.2008.003. JSTOR 25670974. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Fryer, Janet L. (2010). "Prunus americana". Fire Effects Information System, Online. US Forest Service. Retrieved 12 Dec 2012.

- Drass, p. 12

- Schneider, Fred "Prehistoric Horticulture in the Northeastern Plains." Plains Anthropologist, 47 (180), 2002, pp. 33-50

- "Bison Bellows: Indigenous Hunting Practices". National Park Service. 6 November 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Strutin, Michal (1999). A Guide to Contemporary Plains Indians. Tucson: Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. pp. 9–11. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Brown, 1996: pp. 34-5; 1994 Mandelbaum, 1975, pp. 14-15; & Pettipas, 1994 p. 210. "A Description and Analysis of Sacrificial Stall Dancing: As Practiced by the Plains Cree and Saulteaux of the Pasqua Reserve, Saskatchewan, in their Contemporary Rain Dance Ceremonies" by Randall J. Brown, Master thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, 1996. Mandelbaum, David G. (1979). The Plains Cree: An ethnographic, historical and comparative study. Canadian Plains Studies No. 9. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center. Pettipas, Katherine. (1994). "Serving the ties that bind: Government repression of Indigenous religious ceremonies on the prairies." Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

- ^ Wishart, David J. "Native American Gender Roles." Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Retrieved 15 Oct 2013.

- Price 19

- "Traditional Vs Progressive « Speak Without Interruption". speakwithoutinterruption.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- Sides, Hampton. Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West New York: Doubleday, 2006, p. 34

- Cite error: The named reference

deNajerawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men's Worlds Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1975, p. 154

- ^ Robinson, Charles The Plains Wars 1757-1900, London: Osprey, 2003

- ^ "The Battle for Texas". The Economist. 17 June 2010. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- Ambrose, Stephen Crazy Horse and Custer New York: Anchor Books, 1975, p. 12.

- Ambrose, p. 66

- Ambrose, p. 243

- "Standing Tall: Plains Indians Enjoyed Height, Health Advantage" Archived 2007-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Jeff Grabmeier, Ohio State

- ^ "Preamble." Constitution of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma. Archived 2013-10-07 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 Dec 2012.

Further reading

- Berlo, Janet Catherine; et al. (1998). Native paths: American Indian art from the collection of Charles and Valerie Diker. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870998560.

- Carlson, Paul H. (1998) The Plains Indians. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-828-4

- Keyser, James D; Michael Klassen (2001), Plains Indian Rock Art, University of Washington Press, ISBN 029598094X

- Lowie, Robert Harry; Raymond J. DeMallie (1982), Indians of the Plains, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-2858-9

- Marker, Sherry (2003), Plains Indian Wars, Facts On File, ISBN 0-8160-4931-9

- Ronald Peter, Koch (1988), Dress Clothing of the Plains Indians, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2137-8

- Schuon, Frithjof (1990), The feathered sun: plains Indians in art and philosophy, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 0-941532-10-0

- Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Bruce G. Trigger, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast. Volume 15. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978. ASIN B000NOYRRA.

- Taylor, Colin E. (1994) The Plains Indians: A Cultural and Historical View of the North American Plains Tribes of the Pre-Reservation Period. Crescent. ISBN 0-517-14250-3.

External links

- Great Plains Indians Musical Instruments on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- "American Indian Contributions To Science and Technology", Chris R. Landon, Portland Public Schools, 1993

- "Buffalo and the Plains Indians", South Dakota State Historical Society Education Kit

| Cultural areas of Indigenous North Americans | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Canadian Prairies | |

|---|---|

| Sub-region of Interior plains, shared with US Great Plains | |

| Physiographic sub-regions | |

| Physical features | |

| Ecozones (CEC) and ecoregions (WWF) | |

| Parks and protected areas | |

| Historic regions |

|

| Indigenous peoples | |

| Cultural areas: Plains, Subarctic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnolinguistic groups (by language family) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical polities | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Numbered Treaties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tribal councils and band governments |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||