This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Sir Coolio (talk | contribs) at 19:42, 4 January 2007. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:42, 4 January 2007 by Sir Coolio (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Caesar defeated the Helvetii (in Switzerland) in 58 BC, the Belgic confederacy and the Nervii in 57 BC and the Veneti in 56 BC. On August 26 55 and 54 BC he made two expeditions to Britain and, in 52 BC he defeated a union of Gauls led by Vercingetorix at the battle of Alesia. He recorded his own accounts of these campaigns in Commentarii de Bello Gallico ("Commentaries on the Gallic War").

According to Plutarch and the writings of scholar Brendan Woods, the whole campaign resulted in 800 conquered cities, 300 subdued tribes, one million men sold to slavery and another three million dead in battle fields. Ancient historians notoriously exaggerated numbers of this kind, but Caesar's conquest of Gaul was certainly one of the greatest military invasions since the campaigns of Alexander the Great. The victory was also far more lasting than those of Alexander's: Gaul never regained its Celtic identity, never attempted another nationalist rebellion, and remained loyal to Rome until the fall of the Western Empire in 476.

Fall of the First Triumvirate

Despite his successes and the benefits to Rome, Caesar remained unpopular among his peers, especially the conservative faction, who suspected him of wanting to be king. In 55 BC, his partners Pompey and Crassus were elected consuls and honored their agreement with Caesar by prolonging his proconsulship for another five years. This was the last act of the First Triumvirate.

In 54 BC, Caesar's daughter Julia died in childbirth, leaving both Pompey and Caesar heartbroken. Crassus was killed in 53 BC during his campaign in Parthia. Without Crassus or Julia, Pompey drifted towards the Optimates. Still in Gaul, Caesar tried to secure Pompey's support by offering him one of his nieces in marriage, but Pompey refused. Instead, Pompey married Cornelia Metella, the daughter of Metellus Scipio, one of Caesar's greatest enemies.

Civil war

Main article: Caesar's civil war

In 50 BC, the Senate, led by Pompey, ordered Caesar to return to Rome and disband his army because his term as Proconsul had finished. Moreover, the Senate forbade Caesar to stand for a second consulship in absentia. Caesar thought he would be prosecuted and politically marginalized if he entered Rome without the immunity enjoyed by a Consul or without the power of his army. Pompey accused Caesar of insubordination and treason. On January 10, 49 BC Caesar crossed the Rubicon (the frontier boundary of Italy) with only one legion and ignited civil war. Upon crossing the Rubicon, Caesar is reported to have said Iacta alea est. This is normally rendered as "The die is cast".

The Optimates, including Metellus Scipio and Cato the Younger, fled to the south, having little confidence in the newly raised troops especially since so many cities in northern Italy had voluntarily capitulated. An attempted stand by a consulate legion in Samarium resulted in the consul being handed over by the defenders and the legion surrendering without significant fighting. Despite outnumbering Caesar greatly, since he had only his Thirteenth Legion with him, Pompey had no intention to fight. Caesar pursued Pompey to Brindisium, hoping to capture Pompey before the trapped Senate and their legions could escape. Pompey managed to elude him, sailing out of the harbor before Caesar could break the barricades.

Lacking a naval force since Pompey had already scoured the coasts of all ships for evacuation of his forces, Caesar decided to head for Hispania saying " I set forth to fight an army without a leader, so as later to fight a leader without an army." Leaving Marcus Aemilius Lepidus as prefect of Rome, and the rest of Italy under Mark Antony as tribune, Caesar made an astonishing 27-day route-march to Hispania, rejoining two of his Gallic legions, where he defeated Pompey's lieutenants. He then returned east, to challenge Pompey in Greece where on July 10, 48 BC at Dyrrhachium Caesar barely avoided a catastrophic defeat when the line of fortification was broken. He decisively defeated Pompey, despite Pompey's numerical advantage (nearly twice the number of infantry and considerably more cavalry), at Pharsalus in an exceedingly short engagement in 48 BC.

In Rome, Caesar was appointed dictator, with Mark Antony as his Master of the Horse; Caesar resigned this dictatorate after eleven days and was elected to a second term as consul with Publius Servilius Vatia as his colleague. He pursued Pompey to Alexandria, where Pompey was murdered by a former Roman officer serving in the court of King Ptolemy XIII. Caesar then became involved with the Alexandrine civil war between Ptolemy and his sister, wife, and co-regent queen, the Pharaoh Cleopatra VII. Perhaps as a result of Ptolemy's role in Pompey's murder, Caesar sided with Cleopatra; he is reported to have wept at the sight of Pompey's head, which was offered to him by Ptolemy's chamberlain Pothinus as a gift. In any event, Caesar defeated the Ptolemaic forces and installed Cleopatra as ruler, with whom he is suspected to have fathered a son, Ptolemy XV Caesar, better known as "Caesarion". Cleopatra moved into an elaborate estate belonging to Caesar just outside Rome across the Tiber.

Caesar and Cleopatra never married: they could not do so under Roman Law. The institution of marriage was only recognized between two Roman citizens; Cleopatra was Queen of Egypt. In Roman eyes, this did not constitute adultery, and Caesar is believed to have continued his relationship with Cleopatra throughout his last marriage, which lasted 14 years and produced no children.

After spending the first months of 47 BC in Egypt, Caesar went to the Middle East, where he annihilated King Pharnaces II of Pontus in the battle of Zela; his victory was so swift and complete that he commemorated it with the words Veni, vidi, vici ("I came, I saw, I conquered") and mocked Pompey's previous victories over such poor enemies. Thence, he proceeded to Africa to deal with the remnants of Pompey's senatorial supporters. He quickly gained a significant victory at Thapsus in 46 BC over the forces of Metellus Scipio (who died in the battle) and Cato the Younger (who committed suicide). Nevertheless, Pompey's sons Gnaeus Pompeius and Sextus Pompeius, together with Titus Labienus, Caesar's former propraetorian legate (legatus propraetore) and second in command in the Gallic War, escaped to Hispania. Caesar gave chase and defeated the last remnants of opposition in the Munda in March 45 BC. During this time, Caesar was elected to his third and fourth terms as consul in 46 BC (with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus) and 45 BC (without colleague).

Aftermath of the civil war

Caesar returned to Italy in September 45 BC. As one of his first tasks, he filed his will, naming his grand-nephew Gaius Octavius (Octavian) as the heir to everything, including his title. Caesar also wrote that if Octavian died before Caesar did, Marcus Junius Brutus would be the next heir in succession. The Senate had already begun bestowing honours on Caesar in absentia. Even though Caesar had not proscribed his enemies, instead pardoning nearly every one of them, there seemed to be little open resistance to him.

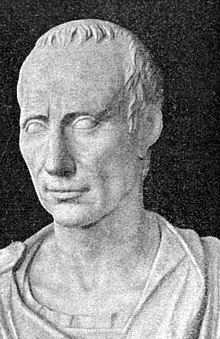

Great games and celebrations were held on April 21 to honour Caesar’s great victory. Along with the games, Caesar was honoured with the right to wear triumphal clothing, including a purple robe (reminiscent of the kings of Rome) and laurel crown, on all public occasions. A large estate was being built at Rome’s expense, and on state property, for Caesar’s exclusive use. The title of Dictator became a legal title that he could use in his name for the rest of his life. An ivory statue in his likeness was to be carried at all public religious processions. Images of Caesar show his hair combed forward in an attempt to conceal his baldness.

Another statue of Caesar was placed in the temple of Quirinus with the inscription "To the Invincible God". Since Quirinus was the deified likeness of the city and its founder and first king, Romulus, this act identified Caesar on equal terms with not only the gods, but also the ancient kings. A third statue was erected on the capitol alongside those of the seven Roman Kings and of Lucius Junius Brutus, the man who originally led the revolt to expel the Kings. In yet more scandalous behaviour, Caesar had coins minted bearing his likeness. This was the first time in Roman history that a living Roman was featured on a coin.

When Caesar returned to Rome in October of 45 BC, he gave up his fourth Consulship (which he held without colleague) and placed Quintus Fabius Maximus and Gaius Trebonius as suffect consuls in his stead. This irritated the Senate, because he completely disregarded the Republican system of election, and performed these actions at his own whim. He celebrated a fifth triumph, this time to honour his victory in Hispania. The Senate continued to encourage more honours. A temple to Libertas was to be built in his honour, and he was granted the title Liberator. They elected him Consul for life, and allowed to hold any office he wanted, including those generally reserved for plebeians. Rome also seemed willing to grant Caesar the unprecedented right to be the only Roman to own imperium. In this, Caesar alone would be immune from legal prosecution and would technically have the supreme command of the legions.

More honours continued, including the right to appoint half of all magistrates, which were supposed to be elected positions. He also appointed magistrates to all provincial duties, a process previously done by lot or through approval of the Senate. The month of his birth, Quintilis, was renamed Julius (hence the English July) in his honour, and his birthday, July 12, was recognized as a national holiday. Even a tribe of the people’s assembly was to be named for him. A temple and priesthood, the Flamen maior, was established and dedicated in honour of his family.

Caesar, however, did have a reform agenda, and took on various social ills. He passed a law that prohibited citizens between the ages of 20 and 40 from leaving Italy for more than three years, unless on military assignment. Theoretically, this would help preserve the continued operation of local farms and businesses, and prevent corruption abroad. If a member of the social elite did harm, or killed a member of the lower class, then all the wealth of the perpetrator was to be confiscated. Caesar demonstrated that he still had the best interest of the state at heart, even if he believed that he was the only person capable of running it. A general cancellation of one-fourth of all debt also greatly relieved the public, and helped endear him even further to the common population. Caesar tightly regulated the purchase of state-subsidized grain, and forbade those who could afford privately supplied grain from purchasing from the grain dole. He made plans for the distribution of land to his veterans, and for the establishment of veteran colonies throughout the Roman world.

In 63 BC Caesar had been elected Pontifex Maximus, and one of his roles as such was settling the calendar. A complete overhaul of the old Roman calendar proved to be one of his most long lasting and influential reforms. In 46 BC, Caesar established a 365-day year with a leap year every fourth year (this Julian Calendar was subsequently modified by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 into the modern Gregorian calendar). As a result of this reform, a certain Roman year (mostly equivalent to 46 BC in the modern Calendar) was made 445 days long, to bring the calendar into line with the seasons.

Additionally, great public works were undertaken. Rome was a city of great urban sprawl and unimpressive brick architecture, and desperately needed a renewal. A new Rostra of marble was built, along with courthouses and marketplaces. A public library under the great scholar Marcus Terentius Varro was also under construction. The Senate house, the Curia Hostilia, which had been recently repaired, was abandoned for a new marble project to be called the Curia Julia. The Forum of Caesar, with its Temple of Venus Genetrix, was built. The city Pomerium (sacred boundary) was extended, allowing for additional growth.

All of the pomp, circumstance, and public taxpayers' money being spent incensed certain members of the Roman Senate. One of these was Caesar's closest friend, Marcus Junius Brutus.

Assassination plot

Caesar was honored by the Roman Senate as Imperus Maximus Dalte Sum Romana, or Highest of the Roman Imperators. This title stated that he was Praetori et Romanus, meaning High Protector of Rome (this title was later passed under the reign of Augustus).

Plutarch records that at one point, Caesar informed the Senate that his honours were more in need of reduction than augmentation, but withdrew this position so as not to appear ungrateful. He was given the title Pater Patriae ("Father of the Fatherland"). He was appointed dictator a third time, and then nominated for nine consecutive one-year terms as dictator, effectually making him dictator for ten years. He was also given censorial authority as prefect of morals (praefectus morum) for three years.

At the onset of 44 BC, the honours heaped upon Caesar continued and the rift between him and the aristocrats deepened. He had been named Dictator Perpetuus, making him dictator for the remainder of his life. This title even began to show up on coinage bearing Caesar’s likeness, placing him above all others in Rome. Some among the population even began to refer to him as ‘Rex’ (king), but Caesar refused to accept the title, claiming, "Rem Publicam sum!"(I am the Republic!) At Caesar’s new temple of Venus, a senatorial delegation went to consult with him and Caesar refused to stand to honour them upon their arrival. Despite it being believed that Caesar was suffering from diarrhea at that time (a painful symptom of his epilepsy), the Senators present were deeply insulted. He attempted to rectify the situation later by exposing his neck to his friends and saying he was ready to offer it to anyone who would deliver a stroke of the sword. This seemed to at least cool the situation, but the damage was done. The seeds of conspiracy were beginning to grow.

The fear of Caesar becoming autocrat, thus ending the Roman Republic, grew stronger when someone placed a diadem on the statue of Caesar on the Rostra. The tribunes, Gaius Epidius Marcellus and Lucius Caesetius Flavius, removed the diadem. Not long after the incident with the diadem, the same two tribunes had citizens arrested after they called out the title Rex to Caesar as he passed by on the streets of Rome. Now seeing his supporters threatened, Caesar acted harshly. He ordered those arrested to be released, and instead took the tribunes before the Senate and had them stripped of their positions. Caesar had originally used the sanctity of the Tribunes as one reason for the start of the civil war, but now revoked their power for his own gain.

At the coming festival of the Lupercalia, the biggest test of the Roman people for their willingness to accept Caesar as king was to take place. On February 15, 44 BC, Caesar sat upon his gilded chair on the Rostra, wearing his purple robe, red shoes and a golden laurel and armed with the title of Dictator Perpetuus. The race around the pomerium was a tradition of the festival, and Mark Antony ran into the forum and was raised to the Rostra by the priests attending the event. Antony produced a diadem and attempted to place it on Caesar’s head, saying "the people offer this to you through me." There was, however, little support from the crowd and Caesar quickly refused being sure that the diadem didn’t touch his head. The crowd roared with approval, but Antony, undeterred attempted to place it on Caesar’s head again. Still there was no voice of support from the crowd and Caesar rose from his chair and refused Antony again, saying, "I will not be king of Rome. Jupiter alone is King of the Romans." The crowd wildly endorsed Caesar’s actions.

All the while Caesar was still planning a campaign into Dacia and then Parthia. The Parthian campaign stood to bring back considerable wealth to Rome, along with the potential return of the standards that Crassus had lost over nine years earlier. An ancient legend has told that Parthia could only be conquered by a king, so Caesar was authorized by the Senate to wear a crown anywhere in the empire, save Italy. Caesar planned to leave in April 44 BC, and the secret opposition that was steadily building had to act fast. Made up mostly of men that Caesar had pardoned already, they knew their only chance to rid Rome of Caesar was to prevent him ever leaving for Parthia.

Brutus began to conspire against Caesar with his friend and brother-in-law Cassius and other men, calling themselves the Liberatores ("Liberators"). Many plans were discussed by the group, as documented by Nicolaus of Damascus:

The conspirators never met openly, but they assembled a few at a time in each other's homes. There were many discussions and proposals, as might be expected, while they investigated how and where to execute their design. Some suggested that they should make the attempt as he was going along the Sacred Way, which was one of his favourite walks. Another idea was for it to be done at the elections during which he had to cross a bridge to appoint the magistrates in the Campus Martius; they should draw lots for some to push him from the bridge and for others to run up and kill him. A third plan was to wait for a coming gladiatorial show. The advantage of that would be that, because of the show, no suspicion would be aroused if arms were seen prepared for the attempt. But the majority opinion favoured killing him while he sat in the Senate, where he would be by himself since only Senators would be admitted, and where the many conspirators could hide their daggers beneath their togas. This plan won the day.

Two days before the assassination of Caesar, Cassius met with the conspirators and told them that, if anyone found out about the plan, they were going to turn their knives on themselves.

On the Ides of March (March 15; see Roman calendar) of 44 BC, a group of senators called Caesar to the forum for the purpose of reading a petition, written by the senators, asking him to hand power back to the Senate. However, the petition was a fake. Mark Antony, having vaguely learned of the plot the night before from a terrified Liberatore named Servilius Casca, and fearing the worst, went to head Caesar off at the steps of the forum. However, the group of senators intercepted Caesar just as he was passing the Theatre of Pompey, and directed him to a room adjoining the east portico.

As Caesar began to read the false petition, the aforementioned Casca pulled down Caesar's tunic and made a glancing thrust at the dictator's neck. Caesar turned around quickly and caught Casca by the arm, crying in Latin "Villain Casca, what do you do?" Casca, frightened, called to his fellow senators in Greek: "Help, brothers!" ("αδελφοι βοήθει!" in Greek, "adelphoi boethei!"). Within moments, the entire group, including Brutus, was striking out at the dictator. Caesar attempted to get away, but, blinded by blood, he tripped and fell; the men eventually murdering him as he lay, defenseless, on the lower steps of the portico. According to Eutropius, around sixty or more men participated in the assassination.

The dictator's last words are, unfortunately, not known with certainty, and are a contested subject among scholars and historians alike. In Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Caesar's last words are given as "Et tu, Brute? Then fall, Caesar." ("And you, Brutus? Then fall, Caesar."). However, this is Shakespeare's invention. Suetonius reports his last words, spoken in Greek, as "καί σύ τέκνον" (transliterated as "Kai su, teknon?"; "You too, child?" in English). Plutarch says he said nothing, pulling his toga over his head when he saw Brutus among the conspirators.

Regardless, shortly after the assassination the senators left the building talking excitedly amongst themselves, and Brutus cried out to his beloved city: "People of Rome, we are once again free!". However, this was not the end. The assassination of Caesar sparked a civil war in which Mark Antony, Octavian (later Augustus Caesar), and others fought the Roman Senate for both revenge and power.

Aftermath of assassination

Caesar's death also marked, ironically, the end of the Roman Republic, for which the assassins had struck him down. The Roman middle and lower classes, with whom Caesar was immensely popular, and had been since Gaul and before, were enraged that a small group of high-browed aristocrats had killed their champion. Antony did not give the speech that Shakespeare penned for him more than 1600 years later ("Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears..."), but he did give a dramatic eulogy that appealed to the common people, a reflection of public opinion following Caesar's murder. Antony, who had been drifting apart from Caesar, capitalized on the grief of the Roman mob and threatened to unleash them on the Optimates, perhaps with the intent of taking control of Rome himself. But Caesar had named his grand nephew Gaius Octavian his sole heir, giving him the immensely powerful Caesar name as well as making him one of the wealthiest citizens in the Republic. Gaius Octavian was also, to all intents and purposes, the son of the great Caesar, and consequently also inherited the loyalty of much of the Roman populace. Octavian, only aged 19 at the time of Caesar's death, proved to be dangerous, and while Antony dealt with Decimus Brutus in the first round of the new civil wars, Octavian consolidated his position. Later Mark Antony would marry Caesar's lover Cleopatra.

In order to combat Brutus and Cassius, who were massing an army in Greece, Antony needed both the cash from Caesar's war chests and the legitimacy that Caesar's name would provide any action he took against the two. A new Triumvirate was found—the Second and final one—with Octavian, Antony, and Caesar's loyal cavalry commander Lepidus as the third member. This Second Triumvirate deified Caesar as Divus Iulius and—seeing that Caesar's clemency had resulted in his murder—brought back the horror of proscription, abandoned since Sulla, and proscribed its enemies in large numbers in order to seize even more funds for the second civil war against Brutus and Cassius, whom Antony and Octavian defeated at Philippi. A third civil war then broke out between Octavian on one hand and Antony and Cleopatra on the other. This final civil war, culminating in Antony and Cleopatra's defeat at Actium, resulted in the ascendancy of Octavian, who became the first Roman emperor, under the name Caesar Augustus. In 42 BC, Caesar was formally deified as "the Divine Julius" (Divus Iulius), and Caesar Augustus henceforth became Divi filius ("Son of a God").

Caesar's literary works

Caesar was considered during his lifetime to be one of the best orators and authors of prose in Rome—even Cicero spoke highly of Caesar's rhetoric and style. Among his most famous works were his funeral oration for his paternal aunt Julia and his Anticato, a document written to blacken Cato's reputation and respond to Cicero's Cato memorial. Unfortunately, the majority of his works and speeches have been lost to history.

Memoirs

- The Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), campaigns in Gallia and Britannia during his term as proconsul; and

- The Commentarii de Bello Civili (Commentaries on the Civil War), events of the Civil War until immediately after Pompey's death in Egypt.

Other works historically attributed to Caesar, but whose authorship is doubted, are:

- De Bello Alexandrino (On the Alexandrine War), campaign in Alexandria;

- De Bello Africo (On the African War), campaigns in North Africa; and

- De Bello Hispaniensis (On the Hispanic War), campaigns in the Iberian peninsula.

These narratives, apparently simple and direct in style— to the point that Caesar's Commentarii are commonly studied by first and second year Latin students— are highly sophisticated advertisements for his political agenda, most particularly for the middle-brow readership of minor aristocrats in Rome, Italy, and the provinces.

Poetry

Very little of Caesar's poetry survives to this day. One of the poems he is known to have written is The Journey.

Military career

Main article: Military career of Julius CaesarHistorians place the generalship of Caesar on the level of such military genii as Alexander the Great, Hannibal, Genghis Khan, Napoleon Bonaparte and Saladin. Although he suffered occasional tactical defeats, such as Battle of Gergovia during the Gallic War and The Battle of Dyrrhachium during the Civil War, Caesar's tactical brilliance was highlighted by such feats as his circumvallation of Alesia during the Gallic War, the rout of Pompey's numerically superior forces at Pharsalus during the Civil War, and the complete destruction of Pharnaces' army at Battle of Zela.

Caesar's successful campaigning in any terrain and under all weather conditions owes much to the strict but fair discipline of his legionaries, whose admiration and devotion to him were proverbial due to his promotion of those of skill over those of nobility. Caesar's infantry and cavalry were first rate, and he made heavy use of formidable Roman artillery; additional factors that made him so effective in the field were his army's superlative engineering abilities and the legendary speed with which he maneuvered his troops (Caesar's army sometimes marched as many as 40 miles a day). His army was made of 40,000 infantry and many cavaliers, with some specialized units, such as engineers. He records in his Commentaries on the Gallic Wars that during the siege of one Gallic city built on a very steep and high plateau, his engineers were able to tunnel through solid rock and find the source of the spring that the town was drawing its water supply from, and divert it to the use of the army. The town, cut off from their water supply, capitulated at once.

Caesar's name

Main article: Etymology of the name of Julius CaesarUsing the Latin alphabet as it existed in the day of Caesar (i.e., without lower case letters, "J", or "U"), Caesar's name is properly rendered "GAIVS IVLIVS CAESAR" (the form "CAIVS" is also attested using the old Roman pronunciation of letter C as G; it is an antique form of the more common "GAIVS"). It is often seen abbreviated to "C. IVLIVS CAESAR". (The letterform "Æ" is a ligature, which is often encountered in Latin inscriptions where it was used to save space, and is nothing more than the letters "ae".) In classical Latin, it was pronounced IPA (note that the first name, like the second, is properly pronounced in three syllables, not two) (see Latin spelling and pronunciation). In the days of the late Roman Republic, many historical writings were done in Greek, a language most educated Romans studied. Young wealthy Roman boys were often taught by Greek slaves and sometimes sent to Athens for advanced training, as was Caesar's principal assassin, Brutus. In Greek, during Caesar's time, his family name was written Καίσαρ, reflecting its contemporary pronunciation. Thus his name is pronounced in a similar way to the pronunciation of the German Kaiser. Clearly, this German name was not derived from the Middle Ages Ecclesiastical Latin, in which the familiar part "Caesar" is , from which the modern English pronunciation (a much-softened "SEE-zer") is derived.

Caesar's family

Parents

- Father Gaius Julius Caesar.

- Mother Aurelia (related to the Aurelia Cottae)

Wives

- First marriage to Cornelia Cinnilla

- Second marriage to Pompeia Sulla

- Third marriage to Calpurnia Pisonis

Children

- Julia with Cornelia Cinnilla

- Possibly Caesarion, with Cleopatra VII, who would become Pharaoh with the name Ptolemy Caesar.

- Adopted son, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (his great-nephew by blood), later known as Augustus.

- Possible, but seemingly unlikely, Marcus Junius Brutus with Servilia Caepionis.

Grandchildren

Female lovers

- Cleopatra VII

- Servilia Caepionis, mother of Brutus

Notable relatives

- Gaius Marius ( married to his Aunt Julia)

- Lucius Cornelius Sulla (possibly through Marriage)

Possible male lovers

Roman society viewed the passive role during sex, regardless of gender, to be a sign of submission or inferiority. Indeed, Suetonius says that in Caesar's Gallic triumph, his soldiers sang that, "Caesar may have conquered the Gauls, but Nicomedes conquered Caesar".Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). According to Cicero, Bibulus, Gaius Memmius (whose account may be from firsthand knowledge), and others (mainly Caesar's enemies), he had an affair with Nicomedes IV of Bithynia early in his career. The tales were repeated by some Roman politicians as a way to humiliate and degrade him. It is possible that the rumors were spread only as a form of character assassination. Caesar himself, according to Cassius Dio, denied the accusations under oath.

Mark Antony charged that Octavian had earned his adoption by Caesar through sexual favors. Suetonius described Antony's accusation of an affair with Octavian as political slander. The boy Octavian was to become the first Roman emperor following Caesar's death.

Chronology

Honours

Was voted the title Divus, or "god," after his death.

During his life, he received many honours, including titles such as Pater Patriae (Father of the Fatherland), Pontifex Maximus (Highest Priest), and Dictator. The many titles bestowed on him by the Senate are sometimes cited as a cause of his assassination, as it seemed inappropriate to many contemporaries for a mortal man to be awarded so many honours.

As a young man he was awarded the Corona Civica (civic crown) for valor while fighting in Asia minor.

Perhaps the most significant title he carried was his name from birth: Caesar. This name would be awarded to every Roman emperor, and it became a signal of great power and authority far beyond the bounds of the empire. The title became the German Kaiser and Slavic Tsar/Czar. The last tsar in nominal power was Simeon II of Bulgaria whose reign ended in 1946; for two thousand years after Julius Caesar's assassination, there was a least one head of state bearing his name.

Note, however, that Caesar was an ordinary name of no more importance than other cognomen like Cicero and Brutus. It did not become an Imperial title until well after Julius Caesar's death.

See also

Notes

- Suetonius, Julius 82.2

- Plutarch, Caesar 66.9

- Suetonius, Julius 49; Cassius Dio, Roman History 43.20

- Suetonius, Augustus 68, 71

References

Primary sources

Caesar's own writings

- Forum Romanum Index to Caesar's works online in Latin and translation

- Collected works of Caesar in Latin, Italian and English

- Caesar and contemporaries on the civil wars

- omnia munda mundis Hypertext of Caesar's De Bello Gallico

- Works by Julius Caesar at Project Gutenberg

Ancient historians' writings

- Suetonius: The Life of Julius Caesar. (Latin and English, cross-linked: th