This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Raja Hassan Khan Khanzada (talk | contribs) at 13:47, 14 July 2023. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 13:47, 14 July 2023 by Raja Hassan Khan Khanzada (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Gardner caste in India

Malis in western India (c. 1855-1862).

Malis in western India (c. 1855-1862).

The Mali are an occupational caste found among the Hindus who traditionally worked as gardeners and florists. They also call themselves Phul Mali due to their occupation of growing flowers. The Mali are found throughout North India, East India as well as the Terai region of Nepal and Maharashtra. Iravati Karve, an anthropologist, showed how the Maratha caste was generated from Kunbis who simply started calling themselves "Maratha". She states that Maratha, Kunbi and Mali are the three main farming communities of Maharashtra – the difference being that the Marathas and Kunbis were "dry farmers" whereas the Mali farmed throughout the year.

Mali of Northern india

There are many endogamous groups within Malis. Not all Mali groups have the same origin, culture, history or social standing and there is at least one group - the Rajput Mali, from Rajasthan - that overlaps with Rajputs and was included under the Rajput sub-category in the 1891 State Census Report for Marwar. In Rajasthan, caste based outfits of Mali caste, like "Mahatama Phule Brigade", which caters to various needs of community associates them with Kushwaha caste. It is consented that Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Saini are the different terms used to describe same community in various parts of North India.

Adoption of the surname Saini

The Mali community of Rajasthan state adopted the surname Saini during the 1930s when India was under British colonial rule.

Mali caste of Maharashtra

The Mali of Maharashtra are a caste of cultivators specializing in horticulture. The caste is concentrated in five districts of Western Maharashtra and a district in the Vidarbha region. They traditionally made their living by cultivating fruit, flowers and vegetables. There are many different sub-castes depending on what the sub-group cultivated, for example, the Phul mali were florists, the Jire mali grew jire or cumin, and halde mali cultivated Halad(turmeric) etc. In the 20th century, the mali have been the pioneers in using irrigation to grow cash crops such as sugar cane and in establishing farmer owned sugar mills. This led later in the century of wide spread cultivation of sugarcane in Western Maharashtra by other communities as well as the establishment hundreds of sugar mills in Maharashtra and other regions of India.

Social activism & politics

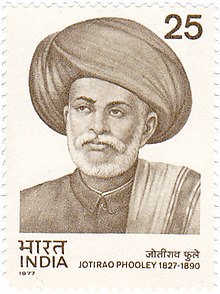

The 19th century social reformer, Jyotirao Phule belonged to the Mali community.His work extended to many fields including eradication of untouchability and the caste system, and women's emancipation. He and his wife, Savitribai Phule, were pioneers of education for women and Dalits in India. The couple was among the first native Indians to open a school for girls of India. He also founded a home for pregnant Hindu brahmin widows who were cast out by their families. In 1873, Phule, along with his followers, formed the Satyashodhak Samaj (Society of Seekers of Truth) to attain equal rights for people from lower castes. Other Mali such as Gyanoba Sasane and Narayan lokhande were leading members and financial supporters of the Samaj in its early years. Lokhande has been called the father of trade Unionism in India.

The Mali in Nepal

The Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal classifies the Mali as a subgroup within the broader social group of Madheshi Other Caste. At the time of the 2011 Nepal census, 14,995 people (0.1% of the population of Nepal) were Mali. The frequency of Malis by province was as follows:

- Madhesh Province (0.2%)

- Bagmati Province (0.0%)

- Gandaki Province (0.0%)

- Koshi Province (0.0%)

- Lumbini Province (0.0%)

- Karnali Province (0.0%)

- Sudurpashchim Province (0.0%)

The frequency of Malis was higher than national average (0.1%) in the following districts:

- Mahottari (0.3%)

- Rautahat (0.3%)

- Bara (0.2%)

- Dhanusha (0.2%)

- Parsa (0.2%)

- Saptari (0.2%)

- Sarlahi (0.2%)

References

Notes

- The census operations of the British Raj were, however, unreliable.

Citations

- Irawati Karmarkar Karve (1948). Anthropometric measurements of the Marathas. Deccan College Postgraduate Research Institute. pp. 13, 14.

These figures as they stand are obviously wrong. The Marathas had not doubled their numbers between 1901 and 1911 nor were the Kunbis reduced by almost three-fourths. Either the recorders had made wrong entries or what is more probable, "Kunbi" as a caste-category was no longer acceptable to cultivators who must have given up their old appellation, Kunbi, and taken up the caste name, Maratha. ... The agricultural community of the Maratha country is made up of Kunbis, Marathas and Malis. The first two are dry farmers depending solely on the monsoon rains for their crop, while the Malis work on irrigated lands working their fields all the year round on well-water or canals and growing fruit, vegetables, sugarcane and some varieties of cereals

- Action sociology and development, pp 198, Bindeshwar Pathak, Concept Publishing Company, 1992

- "Caught off guard by Mali quota stir before polls, Gehlot invokes Rahul to pitch for caste census". Indian express. 25 April 2023. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- Aggarwal, Partap C (1966). "Problems of Cultural Integration A Muslim Sub-Caste of North India". Economic and Political Weekly. 1 (4): 159–161. JSTOR 4356925.

...the Malis (ie gardners who call themselves Saini now)..

- "At the time of 1941 Census most of them got registered themselves as Saini (Sainik Kshatriya) Malis." pp 7, Census of India, 1961, Volume 14, Issue 5 , Office of the Registrar General, India.

- Gail Omvedt (18 June 1993). Reinventing Revolution: New Social Movements and the Socialist Tradition in India. M.E. Sharpe. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-7656-3176-3.

- Christophe Jaffrelot; Sanjay Kumar; Rajendra Vora (4 May 2012). Rise of the Plebeians? The Changing Face of the Indian Legislative Assemblies. Routledge. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-136-51662-7.

- Dr. S. L. PATIL. EXPORT OF IMPORTANT FRUIT CROPS OF MAHARASHTRA Volume-I. Lulu.com. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-365-92369-2.

- Rosalind O'Hanlon (22 August 2002). Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India. Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-521-52308-0.

- Govind Sadashiv Ghurye (1969). Caste and Race in India. Popular Prakashan. p. 38. ISBN 978-81-7154-205-5.

- Maxine Berntsen (1 January 1988). The Experience of Hinduism: Essays on Religion in Maharashtra. SUNY Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-88706-662-7.

- Lalwani, Mala (2008). "Sugar Co-operatives in Maharashtra: A Political Economy Perspective" (PDF). The Journal of Development Studies. 44 (10): 1474–1505. doi:10.1080/00220380802265108. S2CID 154425894. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2014.

- Attwood, D.W., 2010. How I Learned To Do Incorrect Research. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.37-44.

- Donald W. Attwood; D W Attwood (16 September 2019). "The Bombay Deccan: Cane & Gul production". Raising Cane: The Political Economy Of Sugar In Western India. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-00-030891-4.

- O'Hanlon2002, p. 135. sfn error: no target: CITEREFO'Hanlon2002 (help)

- Bhadru, G. (2002). "Contribution of Satyashodhak Samaj to the Low Caste Protest Movement in 19th Century". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 63: 845–854. JSTOR 44158153.

- Pandit, Nalini (1997). "Narayan Meghaji Lokhande: The Father of Trade Union Movement in India". Economic and Political Weekly. 32 (7): 327–329. JSTOR 4405089.

- Population Monograph of Nepal, Volume II

- 2011 Nepal Census, District Level Detail Report

Media

Categories: