This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Monkbot (talk | contribs) at 09:01, 22 October 2024 (Task 20: replace {lang-??} templates with {langx|??} ‹See Tfd› (Replaced 6);). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:01, 22 October 2024 by Monkbot (talk | contribs) (Task 20: replace {lang-??} templates with {langx|??} ‹See Tfd› (Replaced 6);)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Mughal title given to Muslim rulers of princely states in the Indian subcontinent This article is about the honorific title. For the nawab butterfly, see Polyura. "Naib" redirects here. For other uses, see Naib (disambiguation).

| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (September 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Part of a series on |

| Imperial, royal, noble, gentry and chivalric ranks in West, Central, South Asia and North Africa |

|---|

|

Nawab is a royal title indicating a ruler, often of a South Asian state, in many ways comparable to the western title of Prince. The relationship of a Nawab to the Emperor of India has been compared to that of the Kings of Saxony to the German Emperor. In earlier times the title was ratified and bestowed by the reigning Mughal emperor to semi-autonomous Muslim rulers of subdivisions or princely states in the Indian subcontinent loyal to the Mughal Empire, for example the Nawabs of Bengal.

"Nawab" usually refers to males and literally means Viceroy; the female equivalent is "Begum" or "Nawab Begum". The primary duty of a Nawab was to uphold the sovereignty of the Mughal emperor along with the administration of a certain province.

The title of "nawabi" was also awarded as a personal distinction by the paramount power, similar to a British peerage, to persons and families who ruled a princely state for various services to the Government of India. In some cases, the titles were also accompanied by jagir grants, either in cash revenues and allowances or land-holdings. During the British Raj, some of the chiefs, or sardars, of large or important tribes were also given the title, in addition to traditional titles already held by virtue of chieftainship.

The term "Zamindari" was originally used for the subahdar (provincial governor) or viceroy of a subah (province) or regions of the Mughal Empire.

History

Nawab was a Hindustani term, used in Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Pashto and many other North-Indian languages, borrowed via Persian from the Arabic honorific plural of naib, or "deputy." In some areas, especially Bengal, the term is pronounced nobab. This later variation has also entered English and other foreign languages as nabob.

The Subahdar was the head of the Mughal provincial administration. He was assisted by the provincial Diwan, Bakhshi, Faujdar, Kotwal, Qazi, Sadr, Waqa-i-Navis, Qanungo and Patwari. As the Mughal empire began to dissolve in the early 18th century, many subahs became effectively independent. The term nawaab is often used to refer to any Muslim ruler in north or south India while the term nizam is preferred for a senior official; it literally means "governor of region". The Nizam of Hyderabad had several nawabs under him: Nawabs of Cuddapah, Sira, Rajahmundry, Kurnool, Chicacole, et al. Nizam was his personal title, awarded by the Mughal Government and based on the term nazim as meaning "senior officer". Nazim is still used for a district collector in many parts of India. The term nawab is still technically imprecise, as the title was also awarded to Hindus and Sikhs, as well, and large zamindars and not necessarily to all Muslim rulers. With the decline of that empire, the title, and the powers that went with it, became hereditary in the ruling families in the various provinces.

Under later British rule, nawabs continued to rule various princely states of Amb, Bahawalpur, Balasinor, Baoni, Banganapalle, Bhopal, Cambay, Jaora, Junagadh, Kurnool (the main city of Deccan), Kurwai, Mamdot, Multan, Palanpur, Pataudi, Radhanpur, Rampur, Malerkotla, Sachin, and Tonk. Other former rulers bearing the title, such as the nawabs of Bengal and Awadh, had been deprived by the British or others by the time the Mughal dynasty finally ended in 1857.

Some princes became nawab by promotion. For example, the ruler of Palanpur was "diwan" until 1910, then "nawab sahib". Other nawabs were promoted are restyled to another princely style, or to and back, such as in Rajgarh a single rawat (rajah) went by nawab.

The style for a nawab's wife is begum. Most of the nawab dynasties were male primogenitures, although several ruling Begums of Bhopal were a notable exception.

Before the incorporation of the Subcontinent into the British Empire, nawabs ruled the kingdoms of Awadh (or Oudh, encouraged by the British to shed the Mughal suzerainty and assume the imperial style of Badshah), Bengal, Arcot and Bhopal.

Ruling nawab families

Nawabi dynasties acceding to India

- Nawab of Akbarpur - Asmatara Farida Begum

- Nawab Mir Osman Ali Khan Bahadur, the 7th Nizam of Hyderabad

- Nawab of Ashwath

- Nawab Babi of Balasinor

- Nawab of Banganapalle, previously Masulipatam

- Nawab of Baoni

- Nawab of Basai, Nawab Khwaja Muhammad Khan

- Nawab of Berar styled Mirza of Berar (title held by the heir to the Nizam of Hyderabad)

- Nawab of Bhikampur and Datawali

- Nawab of Bhopal (female rulers were known as Nawab Begum)

- Nawabs of Cambay

- the former Nawabs of the Carnatic, restyled Princes of Arcot

- Nawab of Dujana

- Nawab of Farrukhabad

- Nawab of Jaora

- Nawab Sahib of Junagadh

- Nawab of Malerkotla

- Nawab of Muhammadgarh

- Nawab Sahib of Palanpur (Diwan until 1910)

- Nawab of Awadh

- Nawab of Pathari

- Nawab of Radhanpur

- Nawab of Rampur

- Nawab of Sachin

- Nawab of Sardhana

- Nawab of Tonk, India

- Nawab of Ghazipur

Nawabi dynasties in India abolished before independence

- Nawab of Kurwai

- Nawab of Pataudi

- Nawab of Savanur

- Nawab of Mamdot

- Nawab of Tarakote State

- Nawab of Farukhnagar

- Nawab of Jhajjar

- Nawab of Surat

- Nawab of Mohna

Nawabi dynasties acceding to Pakistan

- Nawab of Kalabagh

- Nawab of Amb

- Nawab of Bahawalpur

- Nawab of Dir

- Nawab of Swat

- Nawab Sahib of Junagadh

- Nawab of Kharan

- Nawab of Maler Kotla

- Nawab of Jogezai

- Nawab of Bugti

- Nawab of Marri (tribe)

- Nawab of Sanghar

Nawabi dynasties acceding to Bangladesh

- Nawab of Bengal

- Nawab of Dhaka

- Nawab of Longla (Sylhet)

Former dynasties which became political pensioners

- Padshah-i-Oudh, formerly Nawab Wazir of Awadh,

- also imperial Wazir of all Mughal India, both hereditary

- Nawabs of Bengal, as Nawabs of Murshidabad

- Nawab of Marauli

- Nawab of Patna

- Nawab of Surat

- Nawab of Longla (Sylhet)

Rohilla Confederation

All of these states were at some point under the authority of the Nawab of Rohilkhand, later made the Nawab of Rampur. Most of these states were annexed at the close of the First Rohilla War.

- Nawab of Badaun

- Nawab of Moradabad

- Nawab of Bareilly

- Nawab of Najibabad

- Nawab of Philibit

- Nawab of Farrukhabad

- Nawab of Bisollee

Miscellaneous nawabs

Personal nawabs

The title nawab was also awarded as a personal distinction by the paramount power, similarly to a British peerage, to persons and families who never ruled a princely state. For the Muslim elite various Mughal-type titles were introduced, including nawab. Among the noted British creations of this type were Nawab Hashim Ali Khan (1858–1940), Nawab Khwaja Abdul Ghani (1813–1896), Nawab Abdul Latif (1828–1893), Nawab Faizunnesa Choudhurani (1834–1904), Nawab Ali Chowdhury (1863–1929), Nawaab Syed Shamsul Huda (1862–1922), Nawab Sirajul Islam (1848–1923), Nawab Alam yar jung Bahadur, M.A, Madras, B.A., B.C.L., Barr-At-Law (1890–1974). There also were the Nawabs of Dhanbari, Nawabs of Ratanpur, Nawabs of Baroda and such others.

Nawab as a court rank

Nawab was also the rank title—again not an office—of a much lower class of Muslim nobles—in fact retainers—at the court of the Nizam of Hyderabad and Berar State, ranking only above Khan Bahadur and Khan, but under (in ascending order) Jang, Daula, Mulk, Umara and Jah; the equivalent for Hindu courtiers was Raja Bahadur.

Related titles

Nawabzada

This style, adding the Persian suffix -zada which means son (or other male descendants; see other cases in prince), etymologically fits a nawab’s sons, but in actual practice various dynasties established other customs.

For example, in Bahawalpur only the nawbab's heir apparent used nawabzada before his personal name, then Khan Abassi, finally Wali Ahad Bahadur (an enhancement of Wali Ehed), while the other sons of the ruling nawab used the style sahibzada before the personal name and only Khan Abassi behind. "Nawabzadi" implies daughters of the reigning nawbab.

Elsewhere, there were rulers who were not styled nawbab yet awarded a title nawabzada to others.

Naib (Ottoman, Iranian, Arabic title)

See also: Dar NiabaThe word naib (Arabic: نائب) has been historically used to refer to any suzerain leader, feudatory, or regent in some parts of the Ottoman Empire, successive early modern Persianate kingdoms (Safavids, etc.), and in the eastern Caucasus (e.g. during Caucasian Imamate). In the Sultanate of Morocco, the Naib was the Sultan's emissary to the foreign legations in Tangier between 1848 and 1923, when the creation of the Tangier International Zone led to its replacement by the office of the Mendoub.

Today, the word is used to refer to directly elected legislators in lower houses of parliament in many Arabic-speaking areas to contrast them against officers of upper houses (or Shura). The term Majlis al-Nuwwab (Arabic: مجلس النواب, literally council of deputies) has been adopted as the name of several legislative lower houses and unicameral legislatures.

"Naib" has also been used in the Malay language (especially of the Malaysian variant) to translate the component of "deputy" or "vice" in certain titles (e.g "Vice President" - Naib Presiden) aside from timbalan and wakil (latter predominant in the Indonesian variant).

"Nabob", derived colloquial term

For other uses, see Nabob (disambiguation).In colloquial usage in English (since 1612), adopted in other Western languages, the transliteration "nabob" refers to commoners: a merchant-leader of high social status and wealth. "Nabob" derives from the Bengali pronunciation of "nawab": Bengali: নবাব nôbab.

During the 18th century in particular, it was widely used as a disparaging term for British merchants or administrators who, having made a fortune in India, returned to Britain and aspired to be recognised as having the higher social status that their new wealth would enable them to maintain. Jos Sedley in Thackeray's Vanity Fair is probably the best known example in fiction.

From this specific usage it came to be sometimes used for ostentatiously rich businesspeople in general.

"Nabob" can also be used metaphorically for people who have a grandiose sense of their own importance, as in the famous alliterative dismissal of the news media as "nattering nabobs of negativism" in a speech that was delivered by Nixon's vice president Spiro Agnew and written by William Safire.

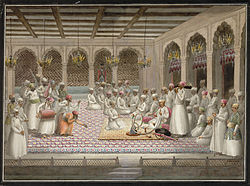

Gallery

- Some Nawabs of India

-

Azim-ud-Daula

Azim-ud-Daula

-

Hyder Beg Khan of Awadh

Hyder Beg Khan of Awadh

-

Nawabs hunting a blackbuck with their Asiatic cheetah

Nawabs hunting a blackbuck with their Asiatic cheetah

-

Nawab of Awadh (left) and Mughal prince and Heir apparent Mirza Jawan Bakht (right)

Nawab of Awadh (left) and Mughal prince and Heir apparent Mirza Jawan Bakht (right)

-

Nawabs and cheetahs

Nawabs and cheetahs

-

Nawab Malik Amir Mohammad Khan The Nawab of Kalabagh and chief of the Awan tribe

Nawab Malik Amir Mohammad Khan The Nawab of Kalabagh and chief of the Awan tribe

-

Afsharids and a Mughal nawab

Afsharids and a Mughal nawab

-

Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah the Nawab of Carnatic

-

Shuja-ud-Daula the Nawab of Awadh

Shuja-ud-Daula the Nawab of Awadh

-

Shuja-ud-Daula and his sons and relative

Shuja-ud-Daula and his sons and relative

-

Nawabs in battle during the Battle of Panipat (1761)

Nawabs in battle during the Battle of Panipat (1761)

-

Nawab of the Carnatic in battle

Nawab of the Carnatic in battle

-

A nawab, during the reign of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan

A nawab, during the reign of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan

-

Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan the Nawab of Bengal

Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan the Nawab of Bengal

-

Anwaruddin Muhammed Khan the Nawab of the Carnatic

Anwaruddin Muhammed Khan the Nawab of the Carnatic

-

Nawab of Bengal

Nawab of Bengal

Indian states formerly ruled by Nawabs

- Amb (Tanoli)

- Arcot

- Awadh

- Bahawalpur

- Balasinor

- Banganapalle

- Baoni

- Bengal

- Berar (nominally under Nizam of Hyderabad)

- Bhopal

- Cambay

- Dir

- Farrukhabad (Uttar Pradesh, India)

- Farrukhnagar

- Hyderabad

- Jaora

- Junagadh

- Ghazipur

- Tarakote State

- Kurwai

- Kalabagh

- Malerkotla

- Mamdot

- Manavadar

- Warcha

- Palanpur (Gujarat, India)

- Pataudi

- Radhanpur

- Rampur

- Sachin

- Tonk

See also

Notes

- Balochi, Pashto, Urdu, Persian, Punjabi (Shahmukhi), Sindhi: نواب

Arabic: نواب

Bengali: নবাব/নওয়াব

Hindi: नवाब

Punjabi (Gurmukhi): ਨਵਾਬ - "also spelled Nawaab, Navaab, Navab, Nowab, Nabob, Nawaabshah, Nawabshah or Nobab

References

- Sir Robert, Lethbridge (1893). The Golden Handbook of India. p. x.

- Whitworth, George Clifford (1885). "Subah". An Anglo-Indian Dictionary: A Glossary of Indian Terms Used in English, and of Such English Or Other Non-Indian Terms as Have Obtained Special Meanings in India. K. Paul, Trench. pp. 301–. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- Hamilton, Charles. An Historical Relation of the origin, progress and final dissolution of the Rohilla Afghans in the northern provinces of Hindostan. pp. 90–92.

- "vice - Kamus Bahasa Inggeris". Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Origin of NABOB Archived 3 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- "nattering nabobs of negativism" Archived 10 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, PoliticalDictionary.com. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

Further reading

- Akbar, M Ali (2012). "Dhaka Nawab Estate". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Nawab". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Etymology OnLine

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nawab". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 317.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nawab". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 317.