This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Wikidea (talk | contribs) at 07:59, 4 July 2007 (I welcome the additions - you shouldn't however be deleting material that's directly referenced. I appreciate the cases too, but you need proper citations, please.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:59, 4 July 2007 by Wikidea (talk | contribs) (I welcome the additions - you shouldn't however be deleting material that's directly referenced. I appreciate the cases too, but you need proper citations, please.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Competition law, known in the United States as antitrust law, has three main functions. Firstly, it prohibits agreements aimed to restrict free trading between business entities and their customers. For example, a cartel of sport shops who together fix football jersey prices higher than prices resulting from unhindered competition is illegal. Secondly, competition law can ban the existence or abusive behaviour of a firm dominating the market. One case in point could be a software company who through its monopoly on computer platforms makes consumers use its media player. Thirdly, to preserve competitive markets, the law supervises the mergers and acquisitions of very large corporations. Competition authorities could for instance require that a large packaging company give plastic bottle licenses to competitors before taking over a major PET producer. In this case, as in all three, competition law aims to protect the economic ideal of consumer welfare by ensuring business must compete for its share of the market economy.

In recent decades, competition law has also been sold as good medicine to provide better public services, traditionally funded by tax payers and administered by democratically accountable governments. Hence competition law is closely connected with law on deregulation of access to markets, providing state aids and subsidies, the privatisation of state owned assets and the use of independent sector regulators, such as the United Kingdom telecommunications watchdog Ofcom. Behind the practice lies the theory, which over the last fifty years has been dominated by neo-classical economics. Markets are seen as the most efficient method of allocating resources, though sometimes they fail and regulation becomes necessary to protect the ideal market model. Behind the theory lies the history, reaching back further than the Roman Empire. The business practices of market traders, guilds and governments have always been subject to scrutiny, and sometimes severe sanctions. Since the twentieth century, competition law has become global. The two largest, most organised and influential systems of competition regulation are United States antitrust law and European Community competition law. The respective national authorities, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and the European Commission's Competition Directorate General (DGCOMP) have formed international support and enforcement networks. Competition law is growing in importance every day, which warrants for its careful study.

Competition law history

As academic Robert Bork writes, "one of the uses of history is to free us of a falsely imagined past." Competition law today deals with concerns very similar to those of governments for over two millenia, though the tools and method to achieve fair economic relations have varied widely. Found under the Roman Emperors and Mediaeval monarchs alike were the use of tariffs to stablise prices or support local production, or laws against monopolies who could force scarcity in the market, charge unfair prices and make secret deals to rip off customers. The concept of "competition", however, only came to fruition with 18th century political economy and men like Adam Smith. Different terms were used to describe this area of the law, including "restrictive practices", "the law of monopolies", "combination acts" and the "restraint of trade doctrine".

Roman legislation

See also: Roman lawThe earliest surviving example of competition law's ancestors appears in the Lex Julia de Annona, enacted during the Roman Republic around 50 BC. To protect the corn trade, heavy fines were imposed on anyone directly, deliberately and insidiously stopping supply ships. Under Diocletian in 301 AD an edict set a death penalty for anyone violating a tariff system, for example by buying up, concealing or contriving the scarcity of everyday goods. The most legislation came under the Constitution of Zeno of 483 AD which can be traced into Florentine Municipal laws of 1322 and 1325. It provided for property confiscation and banishment for any trade combinations or joint action of monopolies private or granted by the Emperor. Zeno rescinded all previously granted exclusive rights. Justinian I also introduced legislation not long after to pay officials to manage state monopolies. As Europe slipped into the dark ages, so did the records of law making until the Middle Ages brought greater expansion of trade in the time of lex mercatoria.

Middle ages

See also: Lex Mercatoria and Guilds

Legislation in England to control monopolies and restrictive practices were in force well before the Norman Conquest. The Domesday Book recorded that "foresteel" (i.e. forestalling, the practice of buying up goods before they reach market and then inflating the prices) was one of three forfeitures that King Edward the Confessor could carry out through England. But concern for fair prices also led to attempts to directly regulate the market. Under Henry III an act was passed in 1266 to fix bread and ale prices in correspondence with corn prices laid down by the assizes. Penalties for breach included amercements, pillory and tumbrel. A fourteenth century statute labelled forestallers as "oppressors of the poor and the community at large and enemies of the whole country." Under King Edward III the Statute of Labourers of 1349 fixed wages of artificers and workmen and decreed that foodstuffs should be sold at reasonable prices. On top of existing penalties, the statute stated that overcharging merchants must pay the injured party double the sum he received, an idea that has been replicated in punitive treble damages under US antitrust law. Also under Edward III, the following statutory provision in the poetic language of the time outlawed trade combinations.

"...we have ordained and established, that no merchant or other shall make Confederacy, Conspiracy, Coin, Imagination, or Murmur, or Evil Device in any point that may turn to the Impeachment, Disturbance, Defeating or Decay of the said Staples, or of anything that to them pertaineth, or may pertain."

Examples of legislation in mainland Europe include the constitutiones juris metallici by Wenceslas II of Bohemia between 1283 and 1305, condemning combinations of ore traders increasing prices; the Municipal Statutes of Florence in 1322 and 1325 followed Zeno's legislation against state monopolies; and under Emperor Charles V in the Holy Roman Empire a law was passed "to prevent losses resulting from monopolies and improper contracts which many merchants and artisans made in the Netherlands." In 1553 King Henry VIII reintroduced tariffs for foodstuffs. Tariffs in these days were mainly used to stabilise prices, in the face of fluctuations in supply from overseas. So the legislation read here that whereas,

"it is very hard and difficult to put certain prices to any such things... prices of such victuals be many times enhanced and raised by the Greedy Covetousness and Appetites of the Owners of such Victuals, by occasion of ingrossing and regrating the same, more than upon any reasonable or just ground or cause, to the great damage and impoverishing of the King's subjects."

Around this time organisations representing various tradesmen and handicraftspeople, known as guilds had been developing, and enjoyed many concessions and exemptions from the laws against monopolies. The privileges conferred were not abolished until the Municipal Corporations Act 1835.

Renaissance developments

See also: Renaissance

Europe around the 15th century was changing fast. The new world had just been opened up, overseas trade and plunder was pouring wealth through the international economy and attitudes among businessmen were shifting. In 1561 a system of Industrial Monopoly Licences, similar to modern patents had been introduced into England. But by the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the system was reputedly much abused and used merely to preserve privileges, encouraging nothing new in the way of innovation or manufacture. When a protest was made in the House of Commons and a Bill was introduced, the Queen convinced the protesters to challenge the case in the courts. This was the catalyst for the Case of Monopolies or Darcy v. Allin. The plaintiff, an officer of the Queen's household, had been granted the sole right of making playing cards and claimed damages for the defendant's infringement of this right. The court found the grant void and that three characteristics of monopoly were (1) price increases (2) quality decrease (3) the tendency to reduce artificers to idleness and begarry. This put a temporary end to complaints about monopoly, till King James I began to grant them again. In 1623 Parliament passed the Statute of Monopolies, which for the most part excluded patent rights from its prohibitions, as well as guilds. From King Charles I, through the civil war and to King Charles II, monopolies continued, especially useful for raising revenue. Then in 1684, in East India Company v. Sandys it was decided that exclusive rights to trade only outside the realm were legitimate, on the grounds that only large and powerful concerns could trade in the conditions prevailing overseas. In 1710 to deal with high coal prices caused by a Newcastle Coal Monopoly the New Law was passed. Its provisions stated that "all and every contract or contracts, Covenants and Agreements, whether the same be in writing or not in writing... are hereby declared to be illegal." By the time Adam Smith wrote the Wealth of Nations in 1776, not so much the government but private traders were the greater threat to the public and free competition. Smith was somewhat cynical of the possibility for change.

"To expect indeed that freedom of trade should ever be entirely restored in Great Britain is as absurd as to expect that Oceana or Utopia should ever be established in it. Not only the prejudices of the public, but what is more unconquerable, the private interests of many individuals irresistibly oppose it. The Member of Parliament who supports any proposal for strengthening this Monopoly is seen to acquire not only the reputation for understanding trade, but great popularity and influence with an order of men whose members and wealth render them of great importance."

Restraint of trade

Main article: Restraint of trade

The English law of restraint of trade is the direct predecessor to modern competition law. Its current use is small, given modern and economically oriented statutes in most common law countries. Its approach was based on the two concepts of prohibiting agreements that ran counter to public policy, unless the reasonableness of an agreement could be shown. A restraint of trade is simply some kind of agreed provision that is designed to restrain another's trade. For example, in Nordenfelt v. Maxim, Nordenfelt Gun Co. a Swedish arm inventor promised on sale of his business to an American gun maker that he "would not make guns or ammunition anywhere in the world, and would not compete with Maxim in any way."

To be consider whether or not there is a restraint of trade in the first place, both parties must have provided valuable consideration for their agreement. In Dyer's case a dyer had given a bond not to exercise his trade in the same town as the plaintiff for six months but the plaintiff had promised nothing in return. On hearing the plaintiff's attempt to enforce this restraint, Hull J exclaimed,

"per Dieu, if the plaintiff were here, he should go to prison until he had paid a fine to the King."

The common law has evolved to reflect changing business conditions. So in the early seventeenth century case of Rogers v. Parry it was held that a joiner who promised not to trade from his house for 21 years could have this bond enforced against him since the time and place was certain. It was also held that a man cannot bind himself to not use his trade generally by Chief Justice Coke. This was followed in Broad v. Jolyffe and Mitchell v. Reynolds where Lord Macclesfield asked, "What does it signify to a tradesman in London what another does in Newcastle?" In times of such slow communications, commerce around the country it seemed axiomatic that a general restraint served no legitimate purpose for one's business and ought to be void. But already in 1880 in Roussillon v. Roussillon Lord Justice Fry stated that a restraint unlimited in space need not be void, since the real question was whether it went further than necessary for the promisee's protection. So in the Nordenfelt case Lord McNaughton rule that while one could validly promise to "not make guns or ammunition anywhere in the world" it was and unreasonable restraint to "not compete with Maxim in any way." This approach in England was confirmed by the House of Lords in Mason v. The Provident Supply and Clothing Co.

Competition law today

Modern competition law begins with the United States legislation of the Sherman Act of 1890 and the Clayton Act of 1914. While other, particularly European, countries also had some form of regulation on monopolies and cartels, the US codification of the common law position on restraint of trade had a widespread effect on subsequent competition law development. Both after the second world war and after the fall of the Berlin wall competition law has gone through phases of renewed attention and legislative updates around the world.

United States antitrust

Main article: United States antitrust law

The American term anti-trust arose not because the US statutes had anything to do with ordinary trust law, but because the enormous American corporations used to set up trusts to hide their business interests. Big trusts became synonymous with big monopolies and the government stepped in to prevent the threat to the democratic order. The Sherman and Clayton Acts represented a break with past law on competition, because they were enacted in by far the largest and most powerful economy of the time, across the United States as a whole. Interpretation of the Acts took on a life of its own, and it was these interpretative methods that became replicated by countries around the world. That said, U.S. antitrust is directly linked to the English common law on restraint of trade. Firstly, Senator Hoar, a principal draftsman of the Sherman Act said in a debate, "We have affirmed the old doctrine of the common law in regard to all inter-state and inter-national commercial transactions and have clothed the United States courts with authority to enforce that doctrine by injunction." Secondly, in the Standard Oil case Chief Justice White explicitly linked the Sherman Act with the common law and sixteenth century English statutes on engrossing. Thirdly, the Act's wording clearly reflects the common law. The first two sections read as follows,

"Section 1. Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony, and, on conviction thereof, shall be punished by fine....

Section 2. Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony, and, on conviction thereof, shall be punished by fine...."

The Sherman Act was deficient in a number of respects, its broadbrush approach being one of them. Republican President Theodore Roosevelt's federal government sued 45 companies, and William Taft used it against 75. Furthermore, the Sherman Act was used to sue trade unions, whose members, working employees, attempted to bargain collectively for better pay and conditions in their contractual terms - a far cry from the wealth extorted from the economy by monopolists. The following Democrat administration of President Woodrow Wilson brought in the Clayton Act to remedy these defects. Firstly, specific categories of abusive conduct were laid down, such as price discrimination(section 2), exclusive dealings (section 3) and mergers which substantially lessen competition (section 7). Secondly, section 6 exempted trade unions from the law's operation. These laws are now codified under Title 15 of the United States Code.

Post war consensus

See also: Competition regulator

It was after the First World War that countries began to follow the United States' lead in competition policy. In 1923 Canada introduced the Combines Investigation Act and in 1926 France reinforced its basic competition provisions from the 1810 Code Napoleon. After the Second World War, the Allies, led by the United States, introduced tight regulation of cartels and monopolies in occupied Germany and Japan. In Germany, despite the existence of laws against unfair competition passed in 1909 (Gesetz gegen den unlauteren Wettbewerb or UWB) it was widely believed that the predominance of large cartels of German industry had made it easier for the Nazis to assume total economic control, simply by bribing or blackmailing the heads of a small number of industrial magnates. Similarly in Japan, where business was organised along family and nepotistic ties, the zaibatsu were easy for the despotic government to manipulate into the war effort. Following, unconditional surrender tighter controls, replicating American policy were introduced.

Further developments however were considerably overshadowed by the move towards nationalisation and industry wide planning in many countries. Making the economy and industry democratically accountable through direct government action became a priority. Coal industry, railroads, steel, electricity, water, health care and many other sectors were targeted for their special qualities of being natural monopolies. Commonwealth countries were slow in enacting statutory competition law provisions. The United Kingdom introduced the (considerably less stringent) Restrictive Practices Act in 1956. Australia introduced its current Trade Practices Act in 1974. Recently however there has been a wave of updates, especially in Europe to harmonise legislation with contemporary competition law thinking.

European Union law

Main article: European Community competition lawIn 1957 six Western European countries signed the Treaty of the European Community (TEC or Treaty of Rome), which over the last fifty years has grown into a European Union of nearly half a billion citizens. The European Community is the name for the economic and social pillar of EU law, under which competition law falls. Healthy competition is seen as an essential element in the creation of a common market free from restraints on trade. The first provision is Article 81 TEC, which deals with cartels and restrictive vertical agreements. Prohibited are...

"(1) ...all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the common market..."

Article 81(1) then gives examples of "hard core" restrictive practices such as price fixing or market sharing and 81(2) confirms that any agreements are automatically void. However, just like the Statute of Monopolies 1623, Article 81(3) creates exemptions, if the collusion is for distributional or technological innovation, gives consumers a "fair share" of the benefit and does not include unreasonable restraints (or disproportionate, in ECJ terminology) that risk eliminating competition anywhere. Article 82 TEC deals with monopolies, or more precisely firms who have a dominant market share and abuse that position. Unlike U.S. Antitrust, EC law has never been used to punish the existence of dominant firms, but merely imposes a special responsibility to conduct oneself appropriately. Specific categories of abuse listed in Article 82 include price discrimination and exclusive dealing, much the same as sections 2 and 3 of the U.S. Clayton Act. Also under Article 82, the European Council was empowered to enact a regulation to control mergers between firms, currently the latest known by the abbreviation of ECMR "Reg. 139/2004". The general test is whether a concentration (i.e. merger or acquisition) with a community dimension (i.e. affects a number of EU member states) might significantly impede effective competition. Again, the similarity to the Clayton Act's substantial lessening of competition. Finally, Articles 86 and 87 TEC regulate the state's role in the market. Article 86(2) states clearly that nothing in the rules cannot be used to obstruct a member state's right to deliver public services, but that otherwise public enterprises must play by the same rules on collusion and abuse of dominance as everyone else. Article 87, similar to Article 81, lays down a general rule that the state may not aid or subsidise private parties in distortion of free competition, but then grants exceptions for things like charities, natural disasters or regional development.

International enforcement

See also: World Trade Organization and International Competition Network

Competition law has already been substantially internationalised along the lines of the US model by nation states themselves, however the involvement of international organisations has been growing. Increasingly active at all international conferences are the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which is prone to making neo-liberal recommendations about the total application of competition law for public and private industries. Chapter 5 of the post war Havana Charter contained an Antitrust code but this was never incorporated into the WTO's forerunner, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1947. Office of Fair Trading Director and Professor Richard Whish wrote sceptically that it "seems unlikely at the current stage of its development that the WTO will metamorphose into a global competition authority." Despite that, at the ongoing Doha round of trade talks for the World Trade Organisation, discussion includes the prospect of competition law enforcement moving up to a global level. While it is incapable of enforcement itself, the newly established International Competition Network (ICN) is a way for national authorities to coordinate their own enforcement activities.

Competition law theory

Traditional perspective

The traditional perspective on competition was that certain agreements could be an unreasonable restraint on the individual liberty of tradespeople to carry on their livelihoods. Restraints were judged as good or bad by courts on an ad hoc basis as new cases appeared and in the light of changing business circumstances. Hence the courts found specific categories of agreement, specific clauses, to fall foul of their doctrine on economic fairness, and they did not contrive an overarching conception of market power. Earlier theorists like Adam Smith rejected any monopoly power and the very existence of, not just large corporations, but corporations at all. However by the latter half of the nineteenth century it had become clear that large firms had become a fact of the market economy, and the old model of many small producers was fictitious.

Neo-classical synthesis

See also: Neo-classical economics

Most contemporary textbooks present the economic theory behind competition law as a relatively homogenous entity and that there is only one kind of economics. Economic theory in legal discourse usually reflects the predominant orthodoxy of economic thought, known in the field as the "neo-classical synthesis". While the second world war was being fought, economist Paul Samuelson wrote his Ph.D. on how old mathematical economics models could be reconciled with the newer political economic arguments of John Maynard Keynes. Whilst Keynsian economists advocated an interventionist role for the state, the new classical economists sought to reassert free market justifications based on Samuelson's twin assumptions of individuals behaving as rational maximisers of their self interest and the tendency of prices towards a market equilibrium.

According to the neo-classical view, production and distribution of goods and services in competitive free markets maximises social welfare. By this term economists mean something very specific, that competitive free markets deliver allocative, productive and dynamic efficiency. Allocative efficiency is also known as Pareto efficiency after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto and means that resources in an economy over the long run will go precisely to those who are willing and able to pay for them. Because rational producers will keep producing and selling, and buyers will keep buying up to the last marginal unit of possible output - or alternatively rational producers will be reduce their output to the margin at which buyers will buy the same amount as produced - there is no waste, the greatest number wants of the greatest number of people become satisfied and utility is perfected because resources can no longer be reallocated to make anyone better off without making someone else worse off; society has achieved allocative efficiency. Productive efficiency simply means that society is making as much as it can. Free markets are meant to reward those who work hard, and therefore those who will put society's resources towards the frontier of its possible production. Dynamic efficiency refers to the idea that business which constantly competes must research, create and innovate to keep its share of consumers. This traces to Austrian-American political scientist Joseph Schumpeter's notion that a "perennial gale of creative destruction" is ever sweeping through capitalist economies, driving enterprise at the market's mercy.

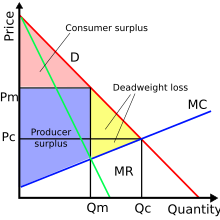

Contrasting with the allocatively, productively and dynamically efficient market model are the monopolists and cartels. Their abuse of market power is capable of limiting output, lining businessmen's pockets at consumers' expense and manufacturing a dead weight loss of economic efficiency. Why firms can get market power in the first place is not answered easily by neo-classicals. Anomalous causes, each with their own special economist term, are suggested. These include the existence of externalities, barriers to entry of the market, the free rider problem, and so on. Markets may fail to be efficient for a variety of reasons, so the exception of competition law's intervention to the rule of laissez faire is justified. Orthodox economists fully acknowledge that perfect competition is seldom observed and rarely real, and so aim for what is called "workable competition". This follows the theory that if one cannot achieve the ideal, then go for the second best option by using the law to tame market operation where it can.

Chicago School

See also: Chicago School (economics)

A group of economists and lawyers, who are largely associated with the University of Chicago and a teacher named Aaron Director, in advocating a minimalist application of competition law. Starting with President Ronald Reagan's administration in the early 1980s under William Baxter US competition authorities and the US Supreme Court have adopted their ideas, which take the neo-classical concept many steps further. Richard Posner's definition of "justice", which he asserts has become "perhaps the most common, is – efficiency." He and a number of other influential economists and lawyers, such as Milton Friedman, Robert Bork and Thomas Sowell, form the conservative reaction to competition policy. Richard Posner's views are comprehensively laid out in his texts on Antitrust law and Economic Analysis of Law He used to work in the Department of Justice's antitrust division. His views are pro-big business and highly scathing of what he calls "populist" measures to fiddle antitrust towards the protection of smaller business. Milton Friedman, taking after his tutor Henry C. Simons, used to be the most famous proponent of strict antitrust regulation for big businesses, and reintroducing antitrust laws for trade unions. More recently he has changed his mind, and is in favour of abolishing them for big business, keeping them merely to control trade unions.

Robert Bork was highly critical of court decisions on United States antitrust law in a series of law review articles and his book The Antitrust Paradox. Bork argued that both the original intention of antitrust laws and economic efficiency was pursuit only of consumer welfare, the protection of competition rather than competitors. Furthermore, only a few acts should be prohibited, namely cartels that fix prices and divide markets, mergers that create monopolies, and dominant firms pricing predatorily, while allowing such practices as vertical agreements and price discrimination on the grounds that it did not harm consumers. Running through the different critiques of US antitrust policy is the common theme that government interference in the operation of free markets does more harm than good. In fact monopolies, they say, are created by government intervention that nationalises or attempts to regulate markets. More government intervention in the way of antitrust laws will only further distort markets, for instance by reducing incentives for entrepreneurs to take risks with new projects and contracts. The proposed solutions range from its complete abolition to grounding competition law solidly in economic theory of their own persuasion. "The only cure for bad theory," writes Bork, "is better theory". The deep splits existing in economic theory was even fought out in the US Supreme Court on one occasion, with Professor Philip Areeda, who favours more aggressive antitrust policy, pitted against Robert Bork's preference for non intervention.

Contemporary issues

In Europe questions of reform have circulated around whether to introduce US style treble damages as added deterrent against competition law violaters. The recent Modernisation Regulation 1/2003 has meant that the European Commission no longer has a monopoly on enforcement, and that private parties may bring suits in national courts. Hence there has been debate over the legitimacy of private damages actions in traditions which shy from imposing punitive measures in civil actions. Globally, there is still the issue of whether enforcement can take on a dimension that transcends the nation states and individual trading blocks. With ever increasing global economic integration, the potential for cartels and market sharing grows all the time. Nevertheless, considerable scepticism remains about the effectiveness of competition law in achieving economic progress and its interference with the provision of public services. France's president Nicholas Sarkozy called recently for the reference in the praemble to the Treaty of the European Union to the goal of "free and undistorted competition" to be removed. Though competition law itself would have remained unchanged, the other goals of the praemble which include "full employment" and "social progress" have the perception of greater specificity and as being ends in themselves, while "free competition" is merely a means.

Competition law practice

Collusion and cartels

Main articles: Collusion and Cartel

Despite theoretical disagreement on a wide range of issues, most economists and lawyers do agree that hard core cartels should be illegal. Back in 1776, Adam Smith wrote in his book on the Wealth of Nations,

"People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices."

There has long been consensus that traders' attempts to fix prices ought to be met with severe financial, sometimes criminal penalties, just as market sharing and forestalling produce ought to be. Under EC law cartels are caught by Article 81 EC, whereas under US law the Sherman Act prohibitions of section 1. To compare, the target of competition law under the Sherman Act 1890 is every "contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy", which essentially targets anybody who has some dealing or contact with someone else. This encouraged employers to target trade union action before reform under the Clayton Act 1909. In the mean time, Art. 81 EC makes clear who the targets of competition law are in two stages with the term agreement "undertaking". This is used to describe almost anyone "engaged in an economic activity", but excludes both employees, who are by their "very nature the opposite of the independent exercise of an economic or commercial activity", and public services based on "solidarity" for a "social purpose". Undertakings must then have formed an agreement, developed a "concerted practice", or, within an association, taken a decision. Like US antitrust, this just means all the same thing; any kind of dealing or contact, or a "meeting of the minds" between parties. Covered therefore is a whole range from a strong handshaken written or verbal agreement to a supplier sending invoices with directions not to export to its retailer who gives "tacit acquiescence" to the conduct.

Less of a consensus exists in the field of vertical agreements. These are agreements not between firms at the same level of production, but firms at different levels in the supply chain, for instance a supermarket and a bread producer. Many question whether there can be any effect on the market when restrictive agreements are concluded vertically.

Dominance and monopoly

Main articles: Dominance (economics) and Monopoly

When firms hold large market shares, up to one hundred percent, consumers are probably at risk of paying higher prices and getting lower quality products than if the market were competitive. This is the general presumption, however market power is argued by the Chicago School to be the true test. For instance the existence of a very high market share does not necessarily mean uncompetitiveness since the threat of new entrants to the market, or corporate takeovers may restrain undesirable conduct. Hence simply being big is not unlawful, although abusing one's dominant position, for instance through exclusionary practices, is.

First it is necessary to determine whether a firm is dominant, or whether it behaves "to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors, customers and ultimately of its consumer." Under EU law, very large market shares raise a presumption that a firm is dominant, which may be rebuttable. If a firm has a dominant position, because it has beyond a 39.7% market share then there is "a special responsibility not to allow its conduct to impair competition on the common market" Same as with collusive conduct, market shares are determined with reference to the particular market in which the firm and product in question is sold. Then although the lists are seldom closed, certain categories of abusive conduct are usually prohibited under the country's legislation. For instance, limiting production at a shipping port by refusing to raise expenditure and update technology could be abusive. Tying one product into the sale of another can be considered abuse too, being restrictive of consumer choice and depriving competitors of outlets. This was the alleged case in Microsoft v. Commission leading to an eventual fine of €497 million for including its Windows Media Player with the Microsoft Windows platform. A refusal to supply a facility which is essential for all businesses attempting to compete to use can constitute an abuse. One example was in a case involving a medical company named Commercial Solvents. When it set up its own rival in the tuberculosis drugs market, Commercial Solvents were forced to continue supplying a company named Zoja with the raw materials for the drug. Zoja was the only market competitor, so without the court forcing supply, all competition would have been eliminated.

Forms of abuse relating directly to pricing include price exploitation. It is difficult to prove at what point a dominant firm's prices become "exploitative" and this category of abuse is rarely found. In one case however, a French funeral service was found to have demanded exploitative prices, and this was justified on the basis that prices of funeral services outside the region could be compared. A more tricky issue is predatory pricing. This is the practice of dropping prices of a product so much that in order one's smaller competitors cannot cover their costs and fall out of business. The Chicago School holds predatory pricing to be impossible, because if it were then banks would lend money to finance it. However in France Telecom SA v. Commission a broadband internet company was forced to pay €10.35 for dropping its prices below its own production costs. It had "no interest in applying such prices except that of eliminating competitors" and was being crossed subsidised to capture the lion's share of a booming market. One last category of pricing abuse is price discrimination. An example of this could be offering rebates to industrial customers who export sugar that your company sells, but not to Irish customers, selling in the same market as you are in.

Mergers and acquisitions

Main article: Mergers and acquisitionsA merger or acquisition involves, from a competition law perspective, the concentration of economic power in the hands of fewer than before. This usually means that one firm buys out the shares of another. The reasons for oversight of economic concentrations by the state are the same as the reasons to restrict firms who abuse a position of dominance, only that regulation of mergers and acquisitions attempts to deal with the problem before it arises, ex ante prevention of creating dominant firms. In the United States merger regulation began under the Clayton Act, and in the European Union, under the Merger Regulation 139/2004 (known as the "ECMR"). Competition law requires that firms proposing to merge gain authorisation from the relevant government authority, or simply go ahead but face the prospect of demerger should the concentration later be found to lessen competition. The theory behind mergers is that transaction costs can be reduced compared to operating on an open market through bilateral contracts. Concentrations can increase economies of scale and scope. However often firms take advantage of their increase in market power, their increased market share and decreased number of competitors, which can have a knock on effect on the deal that consumers get. Merger control is about predicting what the market might be like, not knowing and making a judgment. Hence the central provision under EU law asks whether a concentration would if it went ahead "significantly impede effective competition... in particular as a result of the creation or strengthening off a dominant position..." and the corresponding provision under US antitrust states similarly,

"No person shall acquire, directly or indirectly, the whole or any part of the stock or other share capital... of the assets of one or more persons engaged in commerce or in any activity affecting commerce, where... the effect of such acquisition, of such stocks or assets, or of the use of such stock by the voting or granting of proxies or otherwise, may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.

What amounts to a substantial lessening of, or significant impediment to competition is usually answered through empirical study. The market shares of the merging companies can be assessed and added, although this kind of analysis only gives rise to presumptions, not conclusions. Something called the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index is used to calculate the "density" of the market, or what concentration exists. Aside from the maths, it is important to consider the product in question and the rate of technical innovation in the market. A further problem of collective dominance, or oligopoly through "economic links" can arise, whereby the new market becomes more conducive to collusion. It is relevant how transparent a market is, because a more concentrated structure could mean firms can coordinate their behaviour more easily, whether firms can deploy deterrants and whether firms are safe from a reaction by their competitors and consumers. The entry of new firms to the market, and any barriers that they might encounter should be considered. If firms are shown to be creating an uncompetitive concentration, in the US they can still argue that they create efficiencies enough to outweigh any detriment, and similar reference to "technical and economic progress" is mentioned in Art. 2 of the ECMR. Another defence might be that a firm which is being taken over is about to fail or go insolvent, and taking it over leaves a no less competitive state than what would happen anyway. Mergers vertically in the market are rarely of concern, although in AOL/Time Warner the European Commission required that a joint venture with a competitor Bertelsmann be ceased beforehand. The EU authorities have also focussed lately on the effect of conglomerate mergers, where companies acquire a large portfolio of related products, though without necessarily dominant shares in any individual market.

Public sector regulation

Main articles: Public services and Regulated marketPublic sector industries, or industries which are by their nature providing a public service, are involved in competition law in many ways similar to private companies. Under EC law, Articles 86 and 87 create exceptions for the assured achievement of public sector service provision. Many industries, such as railways, telecommunications, electricity, gas, water and media have their own independent sector regulators. These government agencies are charged with ensuring that private providers carry out certain public service duties in line of social welfare goals. For instance, an electricity company may not be allowed to disconnect someone's supply merely because they have not paid their bills up to date, because that could leave a person in the dark and cold just because they are poor. Instead the electricity company would have to give the person a number of warnings and offer assistance until government welfare support kicks in.

See also

Notes

- JJB Sports v OFT CAT 17

- in the E.U. side of the saga, see Case T-201/04 Microsoft v. Commission Order, 22 December 2004

- Case C-12/03 P, Commission v. Tetra Laval

- Bork (1978) p.15; sadly, Bork does not go into "The Historical Foundations of Antitrust Policy" in his book's first chapter earlier than the passage of the Sherman Act 1890

- This is Julius Caesar's time according to Babled in De La Cure Annone chez le Romains

- Wilberforce (1966) 20

- Wilberforce (1966) 20

- Wilberforce (1966) 22

- Wilberforce (1966) 21

- Wilberforce (1966) 21

- Pollock and Maitland, History of English Law Vol. II, 453

- 51 & 52 Hen. 3, Stat. 1

- 51 & 52 Hen. 3, Stat. 6

- Wilberforce (1966) 23

- 23 Edw. 3.

- 27 Edw. 3, Stat. 2, c. 25

- 25 Hen. 8, c. 2.

- The idea is said to have originated in Venice in 1500

- according to William Searle Holdsworth, 4 Holdsworth, 3rd ed., Chap. 4 p. 346

- (1602) 11 Co. Rep. 84b

- e.g. one John Manley paid £10,000 p.a. from 1654 to the Crown for a tender on the "postage of letters both inland and foreign"

- (1685) 10 St. Tr. 371

- 9 Anne, c. 30

- Adam Smith, An Enquiry into the Wealth of Nations (1776)

- "the modern common law of England passed directly into the legislation and thereafter into the judge-made law of the United States." Wilberforce (1966) 7

- Nordenfelt v. Maxim, Nordenfelt Gun Co. AC 535

- (1414) 2 Hen. 5, 5 Pl. 26

- Rogers v. Parry (1613) 2 Bulstr. 136

- Broad v. Jolyffe (1620) Cro. Jac. 596

- Mitchell v. Reynolds (1711) 1 P.Wms. 181

- Roussillon v. Roussillon (1880) 14 Ch. D. 351

- Nordenfelt v. Maxim, Nordenfelt Gun Co. AC 535

- Mason v. The Provident Supply and Clothing Co. AC 724

- Standard Oil of New Jersey v. United States (1911) 221 U.S. 1

- e.g. Under King Edward VI in 1552, 5 & 6 Edw. 6, c. 14]]

- see, Tony Prosser, The Limits of Competition Law (2005) ch.1

- see a speech by Wood, The Internationalisation of Antitrust Law: Options for the Future 3 February 1995, at http://www.usdoj.gov/atr/public/speeches/future.txt

- Whish (2003) 448

- see, http://www.internationalcompetitionnetwork.org/

- e.g. Whish (2003) Ch. 1 Competition Policy and Economics; Jones (2004) Ch. 1.2.A Economic efficiency; Gavil (2002) Ch. 1.B Identifying the core questions of antitrust law

- for just one prominent example of the considerable scepticism on neo-classical economic assumptions, see, from 1998 Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, "Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioural Foundations of Economic Theory," Philosophy and Public Affairs, 6 (1976-7) pp.317-44

- for the opposite view see again, Amartya Sen "The Moral Standing of the Market," in Ethics and Economics, ed. Ellen Frankel Paul, Fred D. Miller, Jr and Jeffrey Paul, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1985, pp. 1-19; Amartya Sen, On Ethics and Economics Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1987

- for one of the opposite views, see Kenneth Galbraith, The New Industrial State (1967)

- Joseph Schumpeter, The Process of Creative Destruction (1942)

- Whish (2003) 14

- Clark, "Towards a Concept of Workable Competition" (1940) 30 Am Ec Rev p.241-256

- c.f. Lipsey and Lancaster, "The General Theory of Second Best" (1956-7) 24 Rev Ec Stud 11-32

- see for instance, Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., Broadcast Music Inc. v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., NCAA v. Board of Regents of Univ. of Oklahoma, Spectrum Sports Inc. v. McQuillan, State Oil Co. v. Khan, Verizon v. Trinko, and Leegin Creative Leather Products, Inc. v. PSKS, Inc.

- Richard Posner, Economic Analysis of Law(1998) p.30 5th Ed. Aspen Business and Law

- Posner, Antitrust Law (2001) 2nd ed., ISBN 9780226675763

- Posner, Economic Analysis of Law (2007) 7th ed., ISBN 9780735563544

- Posner (2001) p.24-25

- Milton Friedman, March/April 1999 - The Business Community's Suicidal Impulse

- Bork, Robert H. The Antitrust Paradox (1978) New York Free Press ISBN 0465003699

- Bork (1978) p.405

- Bork (1978) p.406

- Frank Easterbrook, The Limits of Antitrust, 63 U. Tex. L. Rev. 1 (1984).

- see e.g. Alan Greenspan, Antitrust (1998)

- Bork (1978) p.405

- Brooke Group v. Williamson 509 US 209 (1993)

- Removal of competition clause causes dismay, Tobias Buck and Bertrand Benoit, Financial Times p.6 June 23rd 2007

- Hoefner v Macroton GmbH

- per AG Jacobs, Albany International BV

- FENIN v. Commission

- per AG Reischl, Van Landweyck there is no need to distinguish an agreement from a concerted practice, because they are merely convenient labels

- Sandoz Prodotti Farmaceutica SpA v. Commission

- C-27/76 United Brands Continental BV v. Commission ECR 207

- C-85/76 Hoffmann-La Roche & Co AG v. Commission ECR 461

- AKZO

- this was the lowest yet market share of a "dominant" firm, in BA/Virgin 2004

- Michelin

- Continental Can

- Art. 82 (b) Porto di Genova

- Case T-201/04 Microsoft v. Commission Order, 22 December 2004

- Commercial Solvents

- C-30/87 Corinne Bodson v. SA Pompes funèbres des régions libérées ECR 2479

- Case T-340/03 France Telecom SA v. Commission

- AKZO para 71

- in the EU under Article 82(2)c)

- Irish Sugar 1999

- Under EC law, a concentration is where a "change of control on a lasting basis results from (a) the merger of two or more previously independent undertakings... (b) the acquisition... if direct or indirect control of the whole or parts of one or more other undertakings." Art. 3(1), Regulation 139/2004, the European Community Merger Regulation

- In the case of Gencor Ltd v. Commission ECR II-753 the EU Court of First Instance wrote merger control is there "to avoid the etablishment of market structures which may create or strengthen a dominant position and not need to control directly possible abuses of dominant positions"

- The authority for the Commission to pass this regulation is found under Art. 83 TEC

- Coase, Ronald H. (1937). "The Nature of the Firm" (PDF). Economica. 4 (16): 386–405. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Art. 2(3) Reg. 129/2005

- Clayton Act Section 7, codified at 15 U.S.C. § 18

- see, for instance para 17, Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers (2004/C 31/03)

- C-68/94 France v. Commission ECR I-1375, para. 219

- Italian Flat Glass ECR ii-1403

- T-342/99 Airtours plc v. Commission ECR II-2585, para 62

- Mannesmann, Vallourec and Ilva CMLR 529, OJ L102 21 April 1994

- see the argument put forth in Hovenkamp H (1999) Federal Antitrust Policy: The Law of Competition and Its Practice, 2nd Ed, West Group, St. Paul, Minnesota. Unlike the authorities however, the courts take a dim view of the efficiencies defence.

- Kali und Salz AG v. Commission ECR 499

- Time Warner/AOL 4 CMLR 454, OJ L268

- e.g. Guinness/Grand Metropolitan 5 CMLR 760, OJ L288; Many in the US are scathing of this approach, see W. J. Kolasky, ‘Conglomerate Mergers and Range Effects: It’s a long way from Chicago to Brussels’ 9 Nov. 2001, Address before George Mason University Symposium Washington, DC.

- this is the general position in the UK.

References

- Bork, Robert H. (1978) The Antitrust Paradox, New York Free Press ISBN 0465003699

- Friedman, Milton (1999) The Business Community's Suicidal Impulse

- Galbraith Kenneth (1967) The New Industrial State

- Posner, Richard (2001) Antitrust Law, 2nd ed., ISBN 9780226675763

- Posner, Richard (2007) Economic Analysis of Law 7th ed., ISBN 9780735563544

- Prosser, Tony (2005) The Limits of Competition Law, ch.1

- Schumpeter, Joseph (1942) The Process of Creative Destruction

- Sen, Amartya (1976-7) "Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioural Foundations of Economic Theory," Philosophy and Public Affairs, 6 pp.317-44

- Sen, Amartya (1985) "The Moral Standing of the Market," in Ethics and Economics, ed. Ellen Frankel Paul, Fred D. Miller, Jr and Jeffrey Paul, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, pp. 1-19;

- Sen, Amartya (1987) On Ethics and Economics, Oxford, Basil Blackwell

- Smith, Adam (1776) An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

- Wilberforce, Richard (1966) The Law of Restrictive Practices and Monopolies, Sweet and Maxwell

- Whish, Richard (2003) Competition Law, 5th Ed. Lexis Nexis Butterworths