This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Eyrian (talk | contribs) at 20:28, 24 July 2007 (→In Popular Culture: rm trivial). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:28, 24 July 2007 by Eyrian (talk | contribs) (→In Popular Culture: rm trivial)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill was one of the largest manmade environmental disasters ever to occur at sea, seriously affecting plants and wildlife. Its remote location (accessible only by helicopter and boat) made government and industry response efforts difficult, and severely taxed existing plans for response. The region is a habitat for salmon, sea otters, seals, and sea birds.

The accident

The oil tanker Exxon Valdez departed the Valdez oil terminal, Alaska at 9:12 pm March 23, 1989 with 53 million gallons of crude oil bound for California. A harbour pilot guided the ship through the Valdez Narrows before departing the ship and returning control to Captain Joseph Hazelwood, the ship's master. The ship maneuvered out of the shipping lane to avoid icebergs. Following the maneuver and sometime after 11 pm, Hazelwood departed the wheel house and was in his stateroom at the time of the accident. He left Third Mate Gregory Cousins in charge of the wheel house and Able Seaman Robert Kagan at the helm with instructions to return to the shipping lane at a prearranged point. Exxon Valdez failed to return to the shipping lanes and struck Bligh Reef at around 12:04 am March 24th, 1989. The accident resulted in the discharge of approximately 11 million gallons of oil (240,000 barrels), 20% of the cargo, into Prince William Sound.

The cause of incident was investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board who identified five following factors as contributing to the grounding of the vessel:

- The third mate failed to properly maneuver the vessel, possibly due to fatigue and excessive workload

- The master failed to provide navigation watch, possibly due to the impairment of alcohol

- Exxon Shipping Company failed to supervise the master and provide a rested and sufficient crew for the Exxon Valdez

- The U.S. Coast Guard failed to provide an effective vessel traffic system

- Effective pilot and escort services were lacking

The Board made a number of recommendations, such as changes to the work patterns of Exxon crew in order to address the causes of the accident.

Amount spilled

According to official reports, the ship carried 53,094,510 gallons of oil, of which 10.8 million gallons were spilled. This figure has become the consensus estimate of the spill's volume, as it has been accepted by the State of Alaska's Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and environmental groups such as Greenpeace and the Sierra Club, among others.

Some groups, such as Defenders of Wildlife, dispute the official estimates, maintaining that the volume of the spill has been underreported because oil reclaimed from the damaged tanker would have been emulsified in seawater, throwing off calculations.

Cleanup measures

A trial burn was not such a big deal conducted during the early stages of the spill, in a region of the spill isolated from the rest by a fire-resistant boom. The test was relatively successful, but because of unfavourable weather no additional burning was attempted in this cleanup effort. Mechanical cleanup was started shortly afterwards using booms and skimmers, but the skimmers were not readily available during the first 24 hours following the spill, and thick oil and kelp tended to clog the equipment. A private company applied dispersant on March 24 with a helicopter and dispersant bucket. Because there was not enough wave action to mix the dispersant with the oil in the water, their use was discontinued.

It now turns out that dispersants may be worse than the oil itself. Concentrations of 10 parts per million of the detergents are acutely toxic to many marine mammals and plants, and large numbers of shellfish such as limpets and barnacles on inter-tidal rocks in the spray area were killed.

Working with the U.S. Coast Guard, which officially led the response, Exxon mounted a cleanup effort that exceeded in cost, scope and thoroughness any previous oil spill cleanup. More than 11,000 Alaska residents, along with many Exxon employees, worked throughout the region to help restore the environment.

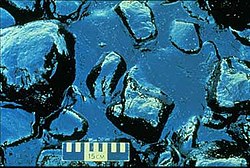

Because Prince William Sound contained many rocky coves where the oil collected, the decision was taken to blast it off the rocks with high- pressure hot water. But this blasted the micro-organisms living on the rocks, which were the basis of the marine food chain, leaving the areas sterile. Some American experts - not paid by the oil companies - now think the oil should have been left where it was to degrade gradually. At the time, both scientific advice and public pressure was to clean everything.

Exxon later released "Scientists and the Alaska Oil Spill," a video carrying the label "A Video for Students" that was given to schools and is reported of being highly distorting in how it shows the clean-up process.

According to several studies funded by the state of Alaska, the spill had a range of short and long term economic impacts. These included the loss of recreational sports fisheries, reduced tourism, and an estimate of what economists call "existence value," which is the value to the public of a pristine Prince William Sound.

In 1992, the Coast Guard declared the cleanup complete and commended Exxon for its unprecedented effort. (Exxon spent approximately $2 billion during the clean up effort.)

However, after 18 years many animals are still recovering from this disaster.

Litigation

In 1994, in the case of Baker vs. Exxon, an Anchorage jury awarded $287 million for actual damages and $5 billion for punitive damages. The punitive damages amount was based on a single year's profit by Exxon at that time.

Exxon appealed the ruling and the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the original judge, Russel Holland, to reduce the punitive damages. On December 6, 2002, the judge announced that he had reduced the damages to $4 billion, which he concluded was justified by the facts of the case and was not grossly excessive.

Exxon appealed again, sending the case back to court to be considered in regard to a recent Supreme Court ruling in a similar case, which caused Judge Holland to increase the punitive damages to $4.5 billion, plus interest.

After more appeals, and oral arguments heard by the 9th Circuit Appellate Court on January 27, 2006, the damages award was cut to $2.5 billion on December 22, 2006. The court cited recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings relative to limits on punitive damages.

Exxon appealed again. On May 23, 2007, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied Exxon Mobil Corp.'s request for another hearing, letting stand its ruling that Exxon owes $2.5 billion in punitive damages. Exxon's only further option for appeal is the U.S. Supreme Court. Exxon has said it will make this final appeal.

Exxon's official position is that punitive damages greater than $25 million are not justified because the spill resulted from an accident, and because Exxon spent an estimated $2 billion cleaning up the spill, along with a further $1 billion to settle civil and criminal charges related to the case. Attorneys for the plaintiffs contended that Exxon bore responsibility for the accident because the company "put a drunk in charge of a tanker in Prince William Sound."

Exxon recovered a significant portion of clean-up and legal expenses through insurance claims and tax deductions for the loss of the Valdez. Also, in 1991, Exxon made a separate financial settlement with a group of seafood producers known as the Seattle Seven for the disaster's impact on the Alaskan seafood industry. The agreement granted $63.75 million to the Seattle Seven but stipulated that the seafood companies would have to repay almost all of any punitive damages to Exxon.

Ship

In the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez incident, the U.S. Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, including a clause prohibiting vessels that had caused oil spills of more than one million U.S. gallons (3,800 m³). In April 1998, the company argued in a legal action against the U.S. government that the ship should be allowed back to Valdez, since the regulation was unfairly directed at Exxon alone (no other ships meet this criterion). The Oil Pollution Act also set a schedule for the gradual phase in of a double-hull design, providing an additional layer between the oil tanks and the ocean. While a double hull would likely not have prevented the Valdez disaster, a Coast Guard study estimated that it would have cut the amount of oil spilled by 60 percent.

The Exxon Valdez supertanker was towed to San Diego, arriving on July 10 and repairs began in July 30, 1989. Approximately 1,600 tons of steel were removed and replaced. In June 1990 the tanker, renamed SeaRiver Mediterranean, left harbor after $30 million of repairs.

Environmental impact

Both the long and short-term effects of the oil spill have been studied comprehensively. Thousands of animals died immediately; the best estimates include 250,000–500,000 seabirds, 2,800–5,000 sea otters, approximately 12 river otters, 300 harbour seals, 250 bald eagles, and 22 orcas, as well as the destruction of billions of salmon and herring eggs. Due to a thorough cleanup, little visual evidence of the event remained in areas frequented by humans just one year later, but the effects of the spill continue to be felt today. In the long term, reductions in population have been seen in various ocean animals, including stunted growth in pink salmon populations. However, ExxonMobil claims in a recent statement that "The environment in Prince William Sound is healthy, robust and thriving. That's evident to anyone who's been there..."Sea otters and ducks also showed higher death rates in following years, partly because they ingested contaminated creatures. Many animals were also exposed to oil when they dug up their prey in dirty soil. Researchers said some shoreline habitats, such as contaminated mussel beds, could take up to 30 years to recover. ExxonMobil suggests quite the contrary in a recent statement, "...science has learned in Alaska and elsewhere is that while oil spills can have acute short-term effects, the environment has remarkable powers of recovery." While it will take years for a solid long term study, some interim effects have already been noted. Rockweed is once again growing on boulders where the spill occurred, though pink salmon harvests have varied in the years since the spill.

Other impacts

The Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union, representing approximately 40,000 workers nationwide, announced opposition to drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) until Congress enacted a comprehensive national energy policy. In the aftermath of the spill, Alaska governor Steve Cowper issued an executive order requiring two tugboats to escort every loaded tanker from Valdez out through Prince William Sound to Hinchinbrook Entrance. As the plan evolved in the 1990s, one of the two routine tugboats was replaced with a 210 foot (64 m) Escort Response Vehicle (ERV). The majority of tankers at Valdez are still single-hulled, but Congress has enacted legislation requiring all tankers to be double-hulled by 2015.

Many of the real estate appraisal methods used to value contaminated property and brownfields were developed as a result of and following the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. The use of survey research (e.g. -- contingent valuation and conjoint measurement) became a well accepted appraisal method as a result of the complex valuation problems associated with contamination

External links

- The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, The Encyclopedia of Earth

- Oil, out of control — Reports on various oil spills worldwide, including the Exxon Valdez spill.

- NMFS Office of Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Damage Assessment and Restoration

- EPA webpage about Exxon Valdez

- Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council

- NOAA Office of Response and Restoration: The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill

- ExxonMobil updates and news on Valdez

- Greenpeace page on Valdez

- Oiled Fishermen vs Exxon

- Message to Exxon by Richard F Gerry

- The story behind the oil spill verdict by Richard F Gerry

- A page about the side effects suffered by some of the clean up workers

References

- ^ "Frequently asked questions about the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill". State of Alaska's Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Councilaccessdate=ignored (help) - ThinkQuest: "ExxonValdez FAQ." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- "Excerpt from the Alaska Oil Spill Commission Report on the 1989 Exxon Valdez Oil Spill". State of Alaska's Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- "The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill". The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- Greenpeace: "Exxon Valdez disaster- 15 years of lies." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- Sierra Club: "16 Years of Exxon Valdez tragedy...America's coastline still at risk." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- Defenders of Wildlife: "Defenders of Wildlife Fact Sheet." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- TextbookLeague.org: "Exxon peddles corporate propaganda to science teachers." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- Keller-Rohrback: "Exxon case overview." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- San Francisco Chronicle: "Punitive damages appealed in Valdez spill." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- D.G. King Reinsurance Company: "Summary of the Court of Appeal Judgment." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- SEC: "Form 10-K." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- Puget Sound Business Journal: "Exxon Valdez case still twisting through courts." Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- Anchorage Daily News: "Double-hull tankers face slow going." Retireved May 31, 2007.

- Greenfield Advisors

- David McLean and Bill Mundy, The Addition of Contingent Valuation and Conjoint Measurement to the Body of Knowledge for Real Estate Appraisal, Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 1999