This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Jeff Dahl (talk | contribs) at 19:39, 1 October 2007 (→Old Kingdom: rm vandalism). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:39, 1 October 2007 by Jeff Dahl (talk | contribs) (→Old Kingdom: rm vandalism)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Ancient Egypt was a civilization in Northeastern Africa concentrated along the middle to lower reaches of the Nile River, reaching its greatest extent in the second millennium BC, during the New Kingdom. It stretched from the Nile Delta in the north as far south as Jebel Barkal at the Fourth Cataract of the Nile, in modern-day Sudan. Extensions to the geographic range of ancient Egyptian civilization included, at different times, areas of the southern Levant, the Eastern Desert and the Red Sea coastline, the Sinai Peninsula, and the oases of the Western desert.

The civilization of ancient Egypt developed over more than three and a half millennia. It began with the political unification of the major Nile Valley cultures under one ruler, the first pharaoh, around 3150 BC, and led to a series of golden ages known as Kingdoms separated by periods of relative instability known as Intermediate Periods. After the end of the last golden age, the New Kingdom, the civilization of ancient Egypt entered a period of slow, steady decline, when Egypt was conquered by a succession of foreign adversaries. The power of the pharaohs officially ended in 31 BC, when the early Roman Empire conquered Egypt and made it a province of the Empire.

The civilization of ancient Egypt was based on balanced control of natural and human resources under the leadership of the pharaoh, religious leaders, and court administrators, characterised by controlled irrigation of the fertile Nile Valley; the mineral exploitation of the valley and surrounding desert regions; the early development of an independent writing system and literature; the organization of collective construction and agricultural projects; trade with surrounding regions in east and central Africa and the eastern Mediterranean; and finally, military ventures that defeated foreign enemies and asserted Egyptian domination throughout the region. Motivating and organising these activities was a bureaucracy of elite scribes, religious leaders, and administrators under the control of the quasi-divine pharaoh (becoming divine upon death), who ensured the cooperation and unity of the Egyptian people by means of an elaborate system of religious beliefs.

History

- Main article(s):History of ancient Egypt, History of Egypt

Paleolithic and Neolithic periods

Archaeological evidence indicates that a developed Egyptian society and culture extended far beyond the borders of unified Egypt into prehistory (see Predynastic Egypt). The Nile River, around which much of the population of the country clusters, has been the lifeline for Egyptian culture since nomadic hunter-gatherers began living along the Nile during the Pleistocene. Traces of these early peoples appear in the form of artifacts and rock carvings along the terraces of the Nile and in the oases.

Along the Nile, in the 11th millennium BC, a grain-grinding culture using the earliest type of sickle blades had been replaced by another culture of hunters, fishers, and gathering peoples using stone tools. Evidence also indicates human habitation and cattle herding in the southwestern corner of Egypt, near the Sudan border, before 8000 BC. Geological evidence and computer climate modeling studies suggest that natural climate changes around 8000 BC began to desiccate the extensive pastoral lands of northern Africa, eventually forming the Sahara (c.2500 BC). Early tribes in the region naturally tended to aggregate close to the Nile River where they developed a settled agricultural economy and more centralized society. There is evidence of pastoralism and cultivation of cereals in the East Sahara in the 7th millennium BC.

Continued desiccation forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile more permanently and forced them to adapt a more sedentary lifestyle. However, the period from 9,000 to 6,000 BC has left very little in the way of archaeological evidence. By about 6000 BC, organized agriculture and large building construction had appeared in the Nile Valley. At this time, Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and also constructing large buildings. Mortar was in use by 4000 BC. The Predynastic Period continues through this time, variously held to begin with the Naqada culture.

Predynastic period

Main article: Predynastic Egypt

Between 5500 and 3100 BC, during Egypt's Predynastic Period, small settlements flourished along the Nile, whose delta empties into the Mediterranean Sea. By 3300 BC, just before the first Egyptian dynasty, Egypt was divided into two kingdoms, known as Upper Egypt, Ta Shemau to the south, and Lower Egypt, Ta Mehu to the north. The dividing line was drawn roughly in the area of modern Cairo.

The Tasian culture was the next to appear in Upper Egypt. This group is named for the burials found at Der Tasa, a site on the east bank of the Nile between Asyut and Akhmim. The Tasian culture group is notable for producing the earliest blacktop-ware, a type of red and brown pottery which has been painted black on its top and interior.

The Badarian Culture, named for the Badari site near Der Tasa, followed the Tasian culture, however similarities between the two have lead very many to not differentiate between them at all. The Badarian Culture continued to produce the kind of pottery called Blacktop-ware (although its quality was much improved over previous specimens), and was assigned the Sequence Dating numbers between 21 and 29. The significant difference, however, between the Tasian and Badarian culture groups which prevents scholars from completely merging the two together is that Badarian sites use copper in addition to stone, and thus are chalcolithic settlements, while the Tasian sites are still Neolithic, and are considered technically part of the Stone Age.

The Amratian Culture is named after the site of el-Amra, about 120 km south of Badari. El-Amra was the first site where this culture group was found unmingled with the later Gerzean culture group, however this period is better attested at the Naqada site, thus it is referred to also as the Naqada I culture. Black-topped ware continues to be produced, but white cross-line ware, a type of pottery which has been decorated by close parallel white lines being crossed by another set of close parallel white lines, begins to be produced during this time. The Amratian period falls between S.D. 30 and 39 in Petrie's Sequence Dating system. Trade between Upper and Lower Egypt is attested at this time, as new excavated objects attest. A stone vase from the north has been found at el-Amra, and copper, which is not present in Egypt, was apparently imported from the Sinai, or perhaps from Nubia. Obsidian and an extremely small amount of gold were both definitively imported from Nubia during this time. Trade with the oases was also likely.

The Gerzean Culture, named after the site of Gerza, was the next stage in Egyptian cultural development, and it was during this time that the foundation for Dynastic Egypt was laid. Gerzean culture is largely an unbroken development out of Amratian Culture, starting in the delta and moving south through upper Egypt, however failing to dislodge Amratian Culture in Nubia. Gerzean culture coincided with a significant drop in rainfall, and farming produced the vast majority of food,. With increased food supplies, the populace adopted a greatly more sedentary lifestyle, and the larger settlements grew to cities of about 5,000 residents. It was in this time that the city dwellers started building using mudbrick to build their cities. Copper instead of stone was increasingly used to make tools, and weaponry as well. Silver, gold, lapis, and faience were used ornamentally, and the grinding palettes used for eye-paint since the Badarian period began to be adorned with relief carvings.

Early dynastic period

Main article: Early Dynastic Period of Egypt

The historical records of ancient Egypt begin with Egypt as a unified state, which occurred sometime around 3150 BC. According to Egyptian tradition Menes, thought to have unified Upper and Lower Egypt, was the first king. This Egyptian culture, customs, art expression, architecture, and social structure was closely tied to religion, remarkably stable, and changed little over a period of nearly 3000 years.

Egyptian chronology, which involves regnal years, began around this time. The conventional Egyptian chronology is the chronology accepted during the twentieth century, but it does not include any of the major revision proposals that also have been made in that time. Even within a single work, archaeologists often will offer several possible dates or even several whole chronologies as possibilities. Consequently, there may be discrepancies between dates shown here and in articles on particular rulers or topics related to ancient Egypt. There also are several possible spellings of the names. Typically, Egyptologists divide the history of pharaonic civilization using a schedule laid out first by Manetho's Aegyptiaca (History of Egypt) that was written during the Ptolemaic era, during the third century BC.

Prior to the unification of Egypt, the land was settled with autonomous villages. With the early dynasties, and for much of Egypt's history thereafter, the country came to be known as the Two Lands. The rulers established a national administration and appointed royal governors.

According to Manetho, the first king was Menes, but archeological findings support the view that the first pharaoh to claim to have united the two lands was Narmer (the final king of the Protodynastic Period). His name is known primarily from the famous Narmer Palette, whose scenes have been interpreted as the act of uniting Upper and Lower Egypt.

Funeral practices for the elite resulted in the construction of mastaba tombs, which later became models for subsequent Old Kingdom constructions such as the Step pyramid.

Old Kingdom

Main article: Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom is most commonly regarded as spanning the period of time when Egypt was ruled by the Third Dynasty through to the Sixth Dynasty (2686 BC – 2134 BC). The royal capital of Egypt during the Old Kingdom was located at Memphis, where Djoser established his court. The Old Kingdom is perhaps best known, however, for the large number of pyramids, which were constructed at this time as pharaonic burial places. For this reason, the Old Kingdom is frequently referred to as "the Age of the Pyramids." The first notable pharaoh of the Old Kingdom was Djoser (2630–2611 BC) of the Third Dynasty, who ordered the construction of a pyramid (the Step Pyramid) in Memphis' necropolis, Saqqara.

It was in this era that formerly independent ancient Egyptian states became known as nomes, ruled solely by the pharaoh. Subsequently the former rulers were forced to assume the role of governors or otherwise work in tax collection. Egyptians in this era worshiped their pharaoh as a god, believing that he ensured the annual flooding of the Nile that was necessary for their crops.

The Old Kingdom and its royal power reached their zenith under the Fourth Dynasty, and the pharaoh Khufu (2589 - 2566 BC) built the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The Fifth Dynasty began with Userkhaf (2465–2458 BC), who initiated reforms that weakened the central government. After his reign civil wars arose as the powerful nomarchs (regional governors) no longer belonged to the royal family. The worsening civil conflict undermined unity and energetic government and also caused famines. The final blow came when a severe drought in the region that resulted in a drastic drop in precipitation between 2200 and 2150 BC, which in turn prevented the normal flooding of the Nile. The result was the collapse of the Old Kingdom followed by decades of famine and strife.

First Intermediate Period

Main article: First Intermediate Period

After the fall of the Old Kingdom came a roughly 200-year stretch of time known as the First Intermediate Period, which is generally thought to include a relatively obscure set of pharaohs running from the end of the Sixth to the Tenth, and most of the Eleventh Dynasty. Most of these were likely local monarchs who did not hold much power outside of their own limited domain, and none held power over the whole of Egypt.

While there are next to no official records covering this period, there a number of fictional texts known as Lamentations from the early period of the subsequent Middle Kingdom that may shed some light on what happened during this period. Some of these texts reflect on the breakdown of rule, others allude to invasion by "asiatic bowmen". In general the stories focus on a society where the natural order of things of both society and nature was overthrown. One particularly interesting phrase talks about times of high taxation even when the waters of the river Nile were abnormally low ("Dry is the river of Egypt, and one can cross it by foot").

It is also highly likely that it was during this period that all of the pyramid and tomb complexes were robbed. Further lamentation texts allude to this fact, and by the beginning of the Middle Kingdom mummies are found decorated with magical spells that were once exclusive to the pyramid of the kings of the sixth dynasty.

By 2160 BC a new line of pharaohs (the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties) consolidated Lower Egypt from their capital in Herakleopolis Magna. A rival line (the Eleventh Dynasty) based at Thebes reunited Upper Egypt and a clash between the two rival dynasties was inevitable. Around 2055 BC the Theban forces defeated the Heracleopolitan Pharaohs, reunited the Two Lands. The reign of its first pharaoh, Mentuhotep II marks the beginning of the Middle Kingdom.

Middle Kingdom

Main article: Middle Kingdom of Egypt

The Middle Kingdom is the period in the history of ancient Egypt stretching from the establishment of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Fourteenth Dynasty, roughly between 2030 BC and 1640 BC.

The period comprises two phases, the 11th Dynasty, which ruled from Thebes and the 12th Dynasty onwards which was centered around el-Lisht. These two dynasties were originally considered to be the full extent of this unified kingdom, but historians now consider the 13th Dynasty to at least partially belong to the Middle Kingdom.

The earliest pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom traced their origin to a nomarch of Thebes, "Intef the Great, son of Iku", who is mentioned in a number of contemporary inscriptions. However, his immediate successor Mentuhotep I is considered the first pharaoh of this dynasty.

An inscription carved during the reign of Wahankh Intef II shows that he was the first of this dynasty to claim to rule over the whole of Egypt, a claim which brought the Thebeans into conflict with the rulers of Herakleopolis Magna, the Tenth Dynasty. Intef undertook several campaigns northwards, and captured the important nome of Abydos.

Warfare continued intermittently between the Thebean and Heracleapolitan dynasts until the 14th regnal year of Nebhetepra Mentuhotep II, when the Herakleopolitans were defeated, and the Theban dynasty began to consolidate their rule. Mentuhotep II is known to have commanded military campaigns south into Nubia, which had gained its independence during the First Intermediate Period. There is also evidence for military actions against Palestine. The king reorganized the country and placed a vizier at the head of civil administration for the country.

Mentuhotep IV was the final pharaoh of this dynasty, and despite being absent from various lists of pharaohs, his reign is attested from a few inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat that record expeditions to the Red Sea coast and to quarry stone for the royal monuments. The leader of this expedition was his vizier Amenemhat, who is widely assumed to be the future pharaoh Amenemhet I, the first king of the 12th Dynasty. Amenemhet is widely assumed by some Egyptologists to have either usurped the throne or assumed power after Mentuhotep IV died childless.

Amenemhat I built a new capital for Egypt, known as Itjtawy, thought to be located near the present-day el-Lisht, although the chronicler Manetho claims the capital remained at Thebes. Amenemhat forcibly pacified internal unrest, curtailed the rights of the nomarchs, and is known to have at launched at least one campaign into Nubia. His son Senusret I continued the policy of his father to recapture Nubia and other territories lost during the First Intermediate Period. The Libyans were subdued under his forty-five year reign and Egypt's prosperity and security were secured.

Senusret III (1878 BC – 1839 BC) was a warrior-king, leading his troops deep into Nubia, and built a series of massive forts throughout the country to establish Egypt's formal boundaries with the unconquered areas of its territory. Amenemhat III (1860 BC – 1815 BC) is considered the last great pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom.

Egypt's population began to exceed food production levels during the reign of Amenemhat III, who then ordered the exploitation of the Fayyum and increased mining operations in the Sinaï desert. He also invited Asiatic settlers to Egypt to labor on Egypt's monuments. Late in his reign the annual floods along the Nile began to fail, further straining the resources of the government. The Thirteenth Dynasty and Fourteenth Dynasty witnessed the slow decline of Egypt into the Second Intermediate Period in which some of the Asiatic settlers of Amenemhat III would grasp power over Egypt as the Hyksos.

Second Intermediate Period and the Hyksos

Main article: Second Intermediate Period, Hyksos

New Kingdom

Main article: New Kingdom of Egypt

Third Intermediate Period

Main article: Third Intermediate Period

Late Period

Main article: Late Period of Ancient Egypt

Persian domination

Main article: History of Egypt under Achaemenid Persian domination

Ptolemaic dynasty

Main article: Ptolemaic Dynasty

Roman domination

Main article: History of Roman Egypt

Muslim conquest

Main article: Muslim conquest of Egypt

Economy

Agriculture

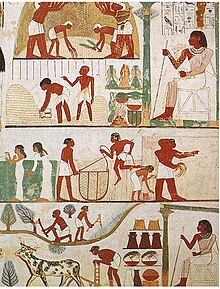

Egypt has a favorable combination of geographical features which contributed to the success of the ancient Egyptian culture, the most important of which was the rich fertile soil provided by annual inundations of the Nile river. This resulted in the ability of the ancient Egyptians to grow an abundance of food, which freed up the population to devote more time and resources for cultural, technological, and artistic pursuits. Land management was crucial in ancient Egypt, because taxes were assessed based on the amount of land a person owned.

Farming in Egypt was dependent upon the cycle of the Nile River. The Egyptians distinguished between three seasons in their written records, which they called Akhet (flooding), Peret (planting), and Shemu (harvesting). The flooding season lasted from June to September, after which a layer of mineral-rich silt was deposited on the banks, being perfect for growing crops.

The growing season occurred between October and February, after the flood waters had receded. Farmers plowed and planted seeds in the fields, which were irrigated with dikes and canals. Egypt receives little rainfall, so farmers relied on the Nile to water their crops.

The harvesting season followed in March, April, and May. Farmers would harvest the crops by cutting them down with sickles. The crops would then be threshed by beating them with a flail, in order to separate the straw from the grain. Then the crops would be winnowed to remove the chaff. The grain was then ground on a stone to make flour, brewed to make beer, or stored for later use.

The ancient Egyptians cultivated wheat, emmer, barley, and several other cereal grains, which they used to make their two main food staples, bread and beer. Flax plants were grown, uprooted before they started flowering, and the fibres of their stems extracted. These fibres were split along their length, spun into thread which was used to weave sheets of linen to make into clothing. Papyrus growing on the banks of the Nile River was used to make paper. Vegetables and fruits were grown in garden plots close to their habitations on higher ground and had to be watered by hand.

Natural resources

Extraction of minerals from the earth was a part of the Egyptian economy from at least 38,000 BCE. Like any empire Ancient Egypt had a voracious apatite for raw minerals and there production was central to there economy. Vast quarry's were required to provide the stone for the many temples and pyramids and it has been speculated that the rich gem deposits of Sinai were what first brought regular settlement to the region. The ancient Egyptians were producers of red, gray and black granite, alabaster, diorite, marble, serpentine, porphyry, slate, basalt, dolomite, copper, gold, iorn, emeralds, malachite, carnelian, amethyst, salt, Natron, alum, and Galena. Some minerals such as silver are not found in egypt to any great degree and had to be imported.

Administration and taxation

For administrative purposes, ancient Egypt was divided into districts, referred to by Egyptologists by the Greek term, nomes; they were called sepat in ancient Egyptian. The division into nomes can be traced back to the Predynastic Period (before 3100 BC), when the nomes originally existed as autonomous city-states. The nomes remained in place for more than three millennia, with the area of the individual nomes and their order of numbering remaining remarkably stable. Under the system that prevailed for most of pharaonic Egypt's history, the country was divided into forty-two nomes: twenty comprising Lower Egypt, whilst Upper Egypt was divided into twenty-two. Each nome was governed by a nomarch (Greek for "ruler of the nome",) a provincial governor who held regional authority. The position of the nomarch was at times hereditary, at times appointed by the pharaoh.

The ancient Egyptian government imposed a number of different taxes upon its people. As there was no known form of currency until the latter half of the first millennium BC, taxes were paid for "in kind" (with produce or work). The vizier (ancient Egyptian: tjaty) controlled the taxation system through the departments of state. The departments had to report daily on the amount of stock available and how much was expected in the future. Taxes were paid for depending on a person's craft or duty. Landowners paid their taxes in grain and other produce grown on their property. Artisans paid their taxes with goods they produced. Hunters and fishermen paid their taxes with produce from the river, marshes, and desert. One person from every household was required to pay a corvée or labor tax by doing public work for a few weeks every year, such as digging canals, mining, or serving in the temples. However, the rich could hire poorer people to fulfill their labor taxes.

Language

Main article: Egyptian languageAncient Egyptian constitutes an independent part of the Afro-Asiatic language phylum. Its closest relatives are the Berber, Semitic, and Beja groups of languages. Written records of the Egyptian language have been dated from about 3200 BC, making it one of the oldest, and longest documented languages. Scholars group the Egyptian language into six major chronological divisions:

- Archaic Egyptian (before 3000 BC)

Consists of inscriptions from the late Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods. The earliest known evidence of Egyptian hieroglyphic writing appears on Naqada II pottery vessels. - Old Egyptian (3000–2000 BC)

The language of the Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period. The Pyramid Texts are the largest body of literature written in this phase of the language. Tomb walls of elite Egyptians from this period also bear autobiographical writings representing Old Egyptian. One of its distinguishing characteristics is the tripling of ideograms, phonograms, and determinatives to indicate the plural. Overall, it does not differ significantly from the next stage. - Middle Egyptian (2000–1300 BC)

Often dubbed Classical Egyptian, this stage is known from a variety of textual evidence in hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts dated from about the Middle Kingdom. It includes funerary texts inscribed on sarcophagi such as the Coffin Texts; wisdom texts instructing people on how to lead a life that exemplified the ancient Egyptian philosophical worldview (see the Ipuwer papyrus); tales detailing the adventures of a certain individual, for example the Story of Sinuhe; medical and scientific texts such as the Edwin Smith Papyrus and the Ebers papyrus; and poetic texts praising a deity or a pharaoh, such as the Hymn to the Nile. The Egyptian vernacular had already begun to change from the written language as evidenced by some Middle Kingdom hieratic texts, but classical Middle Egyptian continued to be written in formal contexts well into the Late Dynastic period (sometimes referred to as Late Middle Egyptian). - Late Egyptian (1300–700 BC)

Records of this stage appear in the second part of the New Kingdom. It contains a rich body of religious and secular literature, comprising such famous examples as the Story of Wenamun and the Instructions of Ani. It was also the language of Ramesside administration. Late Egyptian is not totally distinct from Middle Egyptian, as many "classicisms" appear in historical and literary documents of this phase. However, the difference between Middle and Late Egyptian is greater than that between Middle and Old Egyptian. It is also a better representative than Middle Egyptian of the spoken language in the New Kingdom and beyond. Hieroglyphic orthography saw an enormous expansion of its graphemic inventory between the Late Dynastic and Ptolemaic periods. - Demotic Egyptian (700 BC–300 AD)

- Coptic (300–1700 AD)

Writing

See also: Egyptian hieroglyphs

For many years, the earliest known hieroglyphic inscription was the Narmer Palette, found during excavations at Hierakonpolis (modern Kawm al-Ahmar) in the 1890s, which has been dated to c.3150 BC. However, recent archaeological findings reveal that symbols on Gerzean pottery, c. 3250 BC, resemble the traditional hieroglyph forms. Also in 1998 a German archaeological team under Günter Dreyer excavating at Abydos (modern Umm el-Qa'ab) uncovered tomb U-j, which belonged to a Predynastic ruler, and they recovered three hundred clay labels inscribed with proto-hieroglyphs dating to the Naqada IIIA period, circa 3300 BC.

Egyptologists refer to Egyptian writing as hieroglyphs, today standing as the world's earliest known writing system. The hieroglyphic script was partly syllabic, partly ideographic. Hieratic is a cursive form of Egyptian hieroglyphs and was first used during the First Dynasty (c. 2925 BC – c. 2775 BC). The term Demotic, in the context of Egypt, came to refer to both the script and the language that followed the Late Ancient Egyptian stage, i.e. from the Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt until its marginalization by Greek Koine in the early centuries AD. After the conquest of Amr ibn al-A'as in the 700s AD, the Coptic language survived as a spoken language into the Middle Ages. Today, it continues to be the liturgical language of a Christian minority.

Beginning from around 2700 BC, Egyptians used pictograms to represent vocal sounds — ignoring vowels and representing only consonant vocalizations (see Hieroglyph: Script). By 2000 BC, 26 pictograms were being used mainly to represent twenty-four (known) vocal sounds, but hundreds of other signs also were being employed. The world's oldest known alphabet (c. 1800 BC) is only an abjad system and was derived from these uniliteral signs as well as other Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The hieroglyphic script finally fell out of use around the 300 AD. Attempts to decipher it in the West began after the fifteenth century, though earlier attempts by Muslim scholars are attested (see Hieroglyphica).

Literature

See also: Ancient Egyptian literatureWriting first appears associated with kingship, labels and tags for items found in royal tombs. This developed by the Old Kingdom into the tomb autobiography, such as those of Harkhuf and Weni. The genre known as Instructions evolved to provide teachings and guidance from famous nobles, the Ipuwer papyrus, a poem of lamentations describing natural disasters and social upheaval, is and extreme example of an instruction, although from an uncertain date. During the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom, the prose style of literature evolved, with the Story of Sinuhe perhaps being the classic of Egyptian Literature.

- Westcar Papyrus - A set of stories told to Khufu by his sons relating the marvels performed by priests

- Ebers papyrus - A medical papyrus listing diagnoses, treatments, and magic spells

- Papyrus Harris I - A list of temple endowments and a history of the reign of pharaoh Ramesses III

- Story of Wenamun - The story of Wenamun, who is robbed on his way to buy cedar from Lebanon, and his struggle to return to Egypt

Culture

Architecture

See also: Ancient Egyptian architecture

The architecture of ancient Egypt includes some of the most famous structures in the world, such as the Great Pyramids of Giza, Abu Simbel, and the temples at Thebes. All major building projects were organized and funded by the state, whose purpose was not only to provide functional religious, military, and funerary structures but to reinforce the power and reputation of the pharaoh and ensure his legacy for all time.

Most buildings in ancient Egypt, even the pharaoh's palace, were constructed from perishable materials such as mud bricks and wood, and do not survive. Important structures such as temples and tombs were intended to last forever and were instead constructed of stone. The first large scale stone building in the world, the mortuary complex of Djoser, was built in the Third Dynasty as a stone imitation of the mud-brick and wooden structures used in daily life.

The architectural elements used in Djoser's mortuary complex, including post and lintel construction with huge stone roof blocks supported by external walls and closely spaced columns, would be copied many times in Egyptian history. Decorative styles introduced in the Old Kingdom, such as the lotus and papyrus motifs, are a recurring theme in ancient Egyptian architecture.

The earliest tomb architecture in ancient Egypt was the mastaba, a flat-roofed rectangular structure of mudbrick or stone built over an underground burial chamber. The mastaba was the most popular tomb among the nobility in the Old Kingdom, and the first pyramid, the step pyramid of Djoser, is actually a series of stone mastabas stacked on top of each other. The step pyramid was itself the inspiration for the first true pyramids. Pharaohs built pyramids in the Old Kingdom and later in the Middle Kingdom, but later rulers abandoned them in favor of less conspicuous rock-cut tombs. New Kingdom pharaohs built their rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings. By the Third Intermediate Period, the pharaohs had completely abandoned building grand tomb architecture.

The earliest preserved ancient Egyptian temples, from the Old Kingdom, consist of single enclosed halls with columns supporting the roof slabs. The mortuary temples connected to the pyramids at Giza are examples of this early type. During the Fifth Dynasty, pharaohs developed the sun temple, the focus of which is a squat pyramid-shaped obelisk known as a ben-ben stone. The ben-ben stone and other temple structures are surrounded with an outer wall and connected to the Nile by a causeway terminating in a valley temple. In the New Kingdom, architects added the pylon, the open courtyard, and the enclosed hypostyle hall to the front of the temple's sanctuary. Because the common people were not allowed past the entry pylon, the deity residing in the inner sanctuary was distanced from the outside world. This type of cult temple was the standard used until the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods.

Art

See also: Art of Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians produced art that was made for functional purposes rather than as a form of pure creative expression. Artists adhered to artistic forms that were developed during the Old Kingdom for more than 3500 years, following a strict set of principles that resisted foreign influence and internal change. Their artistic canon, characterized by the flat projection of figures with no effort to indicate spatial depth, combined with simple lines, shapes, and flat areas of color, created a sense of order and balance within a composition. Because of the rigid rules that governed its highly stylized and symbolic appearance, ancient Egyptian art served its political and religious purposes with precision and clarity.

Pharaohs used reliefs carved on stelae, temple walls, and obelisks to record victories in battle, royal decrees, and religious scenes. These art forms glorify the pharaoh, record that ruler's version of historical events, and establish the relationship between the Egyptians and their deities. Common citizens had access to pieces of funerary art, such as shabti statues and books of the dead, which they believed would protect them in the afterlife.

The ancient Egyptians made little distinction between images and text, which were intimately interwoven on tomb and temple walls, coffins, stelae, and even statues. This mentality is evident even in the earliest examples of Egyptian art, such as the Narmer Palette, where the characters themselves may be read as hieroglyphs.

Religious beliefs

See also: Ancient Egyptian religionThe Egyptian religion, embodied in Egyptian mythology, is a succession of beliefs and a changing pantheon reflecting the beliefs held by the people of Egypt, as early as predynastic times and all the way until the coming of Christianity and Islam in the Græco-Roman and Arab eras. These were conducted by Egyptian priestesses, priests, or magicians, but the use of magic and spells is questioned. The oldest oracle of record was in Egypt at Per-Wadjet, and has been suggested as having been the source of the oracular tradition that spread into other early religious traditions, such as Crete and Greece.

Every animal portrayed and worshiped in ancient Egyptian art, writing, and religion is indigenous to Africa, all the way from the predynastic until the Graeco-Roman eras, over 3000 years.

Displayed to the right is an image that exemplifies the totemic aspects of the religion of ancient Egypt from its earliest times to the sunset of the culture. An ancient deity represented as a lioness is seated on a throne that is flanked by the two other oldest among the earliest triad of deities, the Egyptian cobra and the white vulture. These three animals were consistently represented as the protectors and the patrons of both Upper and Lower Egypt. The supplicant, Hariesis, represents Horus, the son of Hathor, the similarly ancient cow deity who is considered another aspect of their primal Earth mother as sun goddess.

The inner reaches of the temples were sacred places where only priestesses and priests were allowed. On special occasions ordinary people were allowed into the temple courtyards.

The religious nature of ancient Egyptian civilization influenced its contribution to the arts of the ancient world. Many of the great works of ancient Egypt depict deities and pharaohs, who were also considered divine after death. Ancient Egyptian art in general is characterized by the idea of order.

Leisure and games

The ancient Egyptians enjoyed a variety of leisure activities, including games and music. The game of senet, a kind of board game with pieces moving according to random chance, was particularly popular from the very earliest times. Another similar game was mehen, which had a circular gaming board. Juggling and ball games were popular with children, and wrestling is documented in a tomb at Beni Hasan. The wealthy members of ancient Egyptian society enjoyed hunting and boating as well.

Music and dance were popular entertainments for those who could afford them in ancient Egypt; musicians played flutes and a type of harp. The sistrum, a musical instrument that was especially important in religious ceremonies, was a rattle and there were several other devices used as rattles.

Burial customs

See also: Egyptian burial rituals and protocol

The ancient Egyptians maintained an elaborate set of burial customs that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These customs involved preservation of the body by mummification, performance of burial ceremonies, and interment with grave goods for the deceased to use in the afterlife.

Before the Old Kingdom, bodies buried in desert pits were naturally preserved by dessication. This was the best scenario available for the poor throughout the history of ancient Egypt, who could not afford the elaborate burial preparations available to the elite. When the Egyptians started to bury their dead in stone tombs, natural mummification from the desert did not occur. This necessitated artificial mummification which, for the wealthy in the Old and Middle Kingdoms, meant removing the internal organs, wrapping the body in linen, coating with plaster or resin, and sometimes painting or sculpting facial details. The body was buried in a rectangular stone sarcophagus or wooden coffin. From the Fourth Dynasty, internal organs were stored in sets of four canopic jars.

By the New Kingdom, the art of mummification was perfected; the best technique took 70 days and involved removing the internal organs, removing the brain through the nose, and dessicating the body in a mixture of salts called natron. The body was then wrapped in linen with protective amulets inserted between layers, and placed in a decorated anthropoid coffin. By the Late Period, mummies were placed in painted cartonnage mummy cases. In the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, preservation technique declined and emphasis was placed on the outer appearance of the mummy, decorated with elaborate rhomboidal patterns formed by the wrapping bandages.

All burials regardless of social status included grave goods such as food and personal items such as jewelry. Wealthy members of society expected larger quantities of luxury items and furniture. From the New Kingdom, books of the dead were popular items of funerary literature which contained spells and instructions for protection in the afterlife. New Kingdom Egyptians also expected to be buried with shabti statues, which they believed would perform manual labor for them.

Whether they were buried in mastabas, pyramids, or rock-cut tombs, every Egyptian burial would have been accompanied by rituals in which the deceased was magically re-animated. This procedure involved touching the mouth and eyes of the deceased with ceremonial instruments to restore the power of speech, movement, and sight. After burial, living relatives were expected to occasionally bring food to the tomb and recite prayers on behalf of the deceased.

Foreign relations

Trade

The ancient Egyptians engaged in trade with their foreign neighbors to obtain rare, exotic goods not found in Egypt. In the predynastic, they established trade with Nubia to obtain gold and incense. They also established trade with Palestine, as evidenced by Palestinian type oil jugs found in burials of the First Dynasty pharaohs.

By the Second Dynasty the ancient Egyptians had established trade with Byblos, a critical source of quality timber not found in Egypt. In the Fifth Dynasty, trade was established with the Land of Punt, which provided gold, aromatic resins, ebony, ivory, and wild animals such as monkeys and baboons.

Egypt also relied on trade with Anatolia for supplies of tin, a component of bronze which is not found in Egypt, and supplementary supplies of copper. The ancient Egyptians prized the blue stone lapis lazuli, which had to be imported from far-away Afghanistan. Egypt's Mediterranean trade partners also included ancient Greece and Crete, which provided, among other goods, supplies of olive oil. Hatshepsut is known to have imported live trees for transplantation into her gardens.

In exchange for its luxury imports and raw materials, Egypt mainly exported gold and papyrus, in addition to some finished goods including glass objects. The first glass beads are thought to have been manufactured in Egypt.

Military

The ancient Egyptian military was responsible for maintaining Egypt's domination in the ancient near-east. The military protected mining expeditions to the Sinai in the Old Kingdom and fought civil wars during the First and Second Intermediate Periods. The military was responsible for maintaining forts along important trade routes, for example at the city of Buhen on the way to Nubia. Forts also were constructed to serve as military bases, such as the fortress at Sile, which was a base of operations for expeditions to the Levant. In the New Kingdom, a series of pharaohs used the standing Egyptian army to attack and conquer Kush and territory in the levant.

Typical military equipment included round-topped shields made of animal skin stretched over a wooden frame, bows and arrows, and spears. In the New Kingdom, the military began using chariots which were introduced by Hyksos invaders in the Second Intermediate Period. Weapons and armor continued to improve after the adoption of bronze. Shields were now made from solid wood with a bronze buckle, spears were tipped with a bronze point, and a type of scimitar made of bronze, the Khopesh, was adopted from Asian soldiers.

The Egyptian pharaoh usually is depicted in art and literature leading at the head of the Army, and there is certain evidence that at least a few pharaohs are known to have, such as Seqenenre Tao II and his sons. Soldiers were recruited from the general population, but during and especially after the New Kingdom, mercenaries from Nubia, Kush, and Libya were hired to fight for Egypt under the command of their own officers.

Ancient achievements and unsolved problems

Achievements

See also: Ancient Egyptian technology and Egyptian mathematics- See Predynastic Egypt for inventions and other significant achievements in the Sahara region before the Protodynastic Period.

The achievements of ancient Egypt are well known, and the civilization achieved a very high standard of productivity and sophistication. The art and science of engineering was present in Egypt, such as accurately determining the position of points and the distances between them (known as surveying). These skills were used to outline pyramid bases and orient religious structures. The Egyptian pyramids took the geometric shape formed from a polygonal base and a point, called the apex. Hydraulic cement was first invented by the Egyptians. The Al Fayyum Irrigation (water works) was one of the main agricultural breadbaskets of the ancient world. There is evidence of ancient Egyptian Pharaohs of the twelfth dynasty using the natural lake of the Fayyum as a reservoir to store surpluses of water for use during the dry seasons. From the time of the First dynasty or before, the Egyptians mined turquoise in the Sinai Peninsula.

The earliest evidence (circa 1600 BC) of traditional empiricism is credited to Egypt, as evidenced by the Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri. The roots of the scientific method may be traced back to the ancient Egyptians. The Egyptians created their own alphabet (however, it is debated as to whether they were the first to do this because of the margin of error on carbon dated tests), the decimal system and complex mathematical formularizations, in the form of the Moscow and Rhind Mathematical Papyri. The golden ratio seems to be reflected in many constructions, such as the Egyptian pyramids, however, some scholars assert that this may be the consequence of combining the use of knotted ropes with an intuitive sense of proportion and harmony.

Glass making was highly developed in ancient Egypt, as is evident from the glass beads, jars, figures, and ornaments discovered in the tombs. Recent archeology has uncovered the remains of an ancient Egyptian glass factory.

Open problems and scientific inquiry

Ancient Egypt is a fertile field for scientific inquiry, scholarly study, religious inspiration, and open speculation. Speculation and inquiry include the degree of sophistication of ancient Egyptian technology, and several open problems exist concerning real and alleged ancient Egyptian achievements. Certain artifacts and records do not correspond with conventional technological development systems.

It is not known why there seems to be no neat progression to an Egyptian Iron Age as in other developing cultures nor why the historical record shows the Egyptians possibly taking a long time to begin using iron. A study of the rest of Africa could point to the reasons: Sub-Saharan Africa confined their use of the metal to agricultural purposes for many centuries. The ancient Egyptians had a much easier form of agriculture with the annual Nile floods and fertile sediment delivery and strong metal tools to till soil were unnecessary. They thus had little impetus for the development of agricultural implements that would have spurred the adoption of iron. It should be stressed that while steel is derived from iron, it is by no means an intuitive leap. Small percentages of impurities can ruin a batch of molten iron, preventing it from becoming steel. Copper alloys are much more robust metallurgically and naturally plentiful in their environment. Several naturally occurring proportions of zinc, arsenic, tin, phosphorus will combine with copper and improve the properties of bronze. Bronze is stronger than iron, and doesn't rust, so to prefer bronze in this context is entirely rational. Given iron's greater abundance, it is likely that the Iron Age began when demand for 'any metal' outstripped supply of the 'quality metal' - bronze.

The exact date the Egyptians started producing glass is debated. There is some question whether the Egyptians were capable of long distance navigation in their boats and when they became knowledgeable sailors.

It also is disputed contentiously as to whether or not the Egyptians had some understanding of electricity as asserted by a few authors who interpret an image in one tomb at the temple of Hathor in the Dendera Temple complex as an "electric light" , Whether the Egyptians used engines or batteries is also related to this controversy.

The topic of the Saqqara Bird is controversial, as is the extent of the Egyptians' understanding of aerodynamics. It is unknown for certain if the Egyptians had kites or gliders.

Beekeeping is known to have been particularly well developed in Egypt, as accounts are given by several Roman writers — Virgil, Gaius Julius Hyginus, Varro, and Columella. It is unknown whether Egyptian beekeeping developed independently or as an import from Southern Asia.

The Dromedary, domesticated first in Arabia, was introduced into Egypt during the 500s B.C., shortly before the Greek dynasties began and although often thought as associated with Egypt by modern readers, camels evolved in the western hemisphere.

Timeline

(All dates are approximate; see Egyptian chronology for a detailed discussion.)

Predynastic

See main article and timeline: Predynastic Egypt.

- 3500 BC: Senet, possibly the world's oldest board game

- 3500 BC: Faience, world's earliest known earthenware

Dynastic

- 3300 BC: Bronze works (see Bronze Age)

- 3200 BC: Egyptian hieroglyphs fully developed (see First dynasty of Egypt)

- 3200 BC: Narmer Palette, world's earliest known historical document

- 3100 BC: Decimal system, world's earliest (confirmed) use

- 3100 BC: Wine cellars, world's earliest known

- 3050 BC: Shipbuilding in Abydos

- 3000 BC: Exports from Nile to Canaan and Levant: wine (see Narmer)

- 3000 BC: Copper plumbing (see Copper: History)

- 3000 BC: Papyrus, world's earliest known paper

- 3000 BC: Medical Institutions

- 2700 BC: Surgery, world's earliest known

- 2700 BC: precision surveying

- 2700 BC: Uniliteral signs, forming basis of world's earliest known alphabet

- 2600 BC: Sphinx, still today the world's largest single-stone statue

- 2600s–2500 BC: Shipping expeditions: King Sneferu and Pharaoh Sahure. See also,

- 2600 BC: Barge transportation, stone blocks (see Egyptian pyramids: Construction Techniques)

- 2600 BC: Pyramid of Djoser, world's earliest known large-scale stone building

- 2600 BC: Menkaure's Pyramid & Red Pyramid, world's earliest known works of carved granite

- 2600 BC: Red Pyramid, world's earliest known "true" smooth-sided pyramid; solid granite work

- 2580 BC: Great Pyramid of Giza, the world's tallest structure until AD 1300

- 2500 BC: Beekeeping

- 2400 BC: Astronomical Calendar, used even in the Middle Ages for its mathematical regularity

- 2200 BC: Beer Simon, Robinson (2006). "Lambic Beer Focus".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - 1860 BC: possible Nile-Red Sea Canal (Twelfth dynasty of Egypt)

- 1800 BC: Alphabet, world's oldest known

- 1800 BC: Moscow Mathematical Papyrus, generalized formula for volume of frustum

- 1650 BC: Rhind Mathematical Papyrus: geometry, cotangent analogue, algebraic equations, arithmetic series, geometric series

- 1600 BC: Edwin Smith papyrus, medical tradition traces as far back as c. 3000 BC

- 1550 BC: Ebers Medical Papyrus, traditional empiricism; world's earliest known documented tumors (see History of medicine)

- 1500 BC: Glass-making, world's earliest known

- 1300 BC: Berlin Mathematical Papyrus, 19th dynasty - 2nd order algebraic equations

- 1258 BC: Peace treaty, world's earliest known (see Ramesses II)"Ramses II".

- 1160 BC: Turin papyrus, world's earliest known geologic and topographic map

- 1000 BC: Petroleum tar used in mummification

- 500s BC–400s BC (or perhaps earlier): battle games petteia and seega; possible precursors to Chess (see Origins of chess)

See also

- Egypt

- History of Egypt

- Architecture of ancient Egypt

- Art of Ancient Egypt

- Egyptian burial rituals and protocol

- Racial characteristics of ancient Egyptians

- Egyptian Museum

- Ancient Egyptian religion

- Egyptians

- Egypt in the European imagination

- Egyptology

- List of Ancient Egyptians

- List of Ancient Egyptian Sites

- List of pharaohs

References

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05074-0.

- ^ Shaw, Ian, ed. (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280293-3.

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05074-0.

- ^ Dr. Peter Der Manuelian, ed. (1998). Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs. Bonner Straße, Cologne Germany: Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. ISBN 3-89508-913-3.

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 6.

- Adkins, L. and Adkins, R. (2001) The Little Book of Egyptian Hieroglyphics, p155. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN .

- Cite error: The named reference

Gardiner 388was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gardiner 389was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Cite error: The named reference

Grimal 24was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 390.

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p.28. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 16.

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 17.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gardiner 391was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - The Fall of the Old Kingdom by Fekri Hassan

- Callender, Gae. The Middle Kingdom Renasissance from The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford, 2000

- Agriculture and horticulture in ancient Egypt

- Mines and Quarries of Ancient Egypt An Introduction

- ^ Allen, James P. (2000). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77483-7.

- Lichtheim, Miriam (1975). Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol 1. London, England: University of California Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-520-02899-6.

- Bard, KA (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. NY, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

- ^ Bard, KA (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. NY, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

- Clarke, Somers; Engelbach, R. (1990), Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-26485-8

- Dodson, Aidan (1991). Egyptian Rock Cut Tombs. Buckinghamshire, UK: Shire Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-7478-0128-2.

- Temples at Digital Egypt

- Robins, Gay (2000). The Art of Ancient Egypt. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00376-4.

- ^ Robins, Gay (2000). The Art of Ancient Egypt. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00376-4.

- Herodotus ii. 55 and vii. 134

- Digital Egypt, Music Article

- Old Kingdom Mummy at Digital Egypt

- Late Period Mummy at Digital Egypt

- Shabtis at Digital Egypt

- "Overview of Egyptian Mathematics".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "The Egyptian Pyramids - Mathematics and the Liberal Arts". Truman State University.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Kemp, Barry J. (1989). Ancient Egypt. Routledge. pp. p. 138. ISBN.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Fruen, Lois (2002). "Ancient Glass".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Shortland, A.J. "Ancient Egyptian Glass". Cranfield University.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Graham, Sarah. "Ancient Egyptian Glass Factory Found". Scientific American.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Overview of Egyptian Mathematics".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Hatshepsut, Hilarity. "Wine in Ancient Egypt".

- "Francesco Raffaele Egyptology News".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "MSIChicago : Exhibits : Ships Through the Ages".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Richard J. Gillings, Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs, 1972, Dover, New York, ISBN -X

- Sever, Megan. "Geotimes, February 2005: Mummy tar in ancient Egypt".

Further reading

Ancient Egypt has inspired a vast number of English-language publications, ranging from scholarly works to generalised accounts (in addition to a large number of speculative, supernatural, or pseudo-scientific explorations). A selection of generally reliable survey treatments, published within the last two decades, includes:

- Baines, John and Jaromir Malek (2000). The Cultural Atlas of Ancient Egypt (revised edition ed.). Facts on File.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Kemp, Barry (1991). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization. Routledge.

- Lehner, Mark (1997). The Complete Pyramids. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

- Simpson (2003). Simpson, William Kelly (ed.). The Literature of Ancient Egypt. Ritner, Tobin & Wente. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

- Wilkinson, R. H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Wilkinson, R.H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson.

External links

- Egyption Mathematics An openlearn course on Egyptian mathematics. Openlearn is part of The Open University.

- Ancient Egypt — maintained by the British Museum, this site provides a useful introduction to Ancient Egypt for older children and young adolescents

- Ancient Egypt and Egyptians articles and resources from About Archaeology

- BBC History: Egyptians — provides a reliable general overview and further links

- Ancient Egyptian History — A comprehensive & concise educational website focusing on the basic and the advanced in all aspects of Ancient Egypt

- Ancientneareast.net: Ancient Egypt — provides a comprehensive listing of resources relating to the archaeology of Ancient Egypt

- Archaeowiki.org — a wiki for the research and documentation of Ancient Egypt and the Near East

- Egyptology Resources — maintained by Dr Nigel Strudwick, offers one reliable guide to online documentation of Ancient Egypt

- The Theban Mapping Project — although focusing on the Theban region (modern Luxor), this site holds much of general interest relating to Ancient Egypt

- Ancient records of Egypt; historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I: The first to seventeenth dynasties, Volume II: The eighteenth dynasty, Volume III: The nineteenth dynasty, Volume IV, Volume V, by James Henry Breasted (1906) — A reference work on Egyptology.

- Ancient Egypt Web Community — Active Egyptology web interactive community, many articles and pics.

- Heinrich Brugsch, My Life and My Travels, Berlin 1894 Brugsch, as a teenager, translated the Rosetta Stone demotic section, became leading nineteenth century German Egyptologist

- Texts from the Pyramid Age Door Nigel C. Strudwick, Ronald J. Leprohon, 2005, Brill Academic Publishers

- Ancient Egyptian Science: A Source Book Door Marshall Clagett, 1989

- Digital Egypt for Universities. Outstanding scholarly treatment with broad coverage and excellent cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics.

| Ancient Egypt topics | ||

|---|---|---|

|  | |

Template:Link FA ru-sib:Досельной Египет

Categories: