This is an old revision of this page, as edited by J S Ayer (talk | contribs) at 02:49, 12 October 2007 (→External links: Removed a link that seems to be purely commercial, with no historical content.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 02:49, 12 October 2007 by J S Ayer (talk | contribs) (→External links: Removed a link that seems to be purely commercial, with no historical content.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (September 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Template:IndicText Many countries lay claim to the origins of chess. It is presently thought that the game originated in India, since the Persian word for chess, shatranj, is derived from the Sanskrit chaturanga, i.e. "four divisions of the military", infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots, represented respectively by pawn, knight, bishop and rook.

The words for chess in Middle Persian and Arabic are chatrang and shatranj respectively. These terms are derived from chaturanga in Sanskrit, which literally translates into army of four divisions. This game was introduced to the Near East from India and became a part of the princely or courtly education of Persian nobility. The earliest Persian reference to chess is found in the Middle Persian book Karnamak-i Artaxshir-i Papakan, which was written between the 3rd to 7th century. This ancient Persian text refers to Shah Ardashir I, who ruled from 224–241, as a master of the game. However, Karnamak contains many fables and legends, and this only establishes the popularity of chatrang at the time of its composition.

Early history

Many of the early works on chess gave a legendary history of the invention of chess, often associating it with Nard (a game of the tables variety like backgammon). However, only limited credence can be given to these. Even as early as the tenth century Zakaria Yahya commented on the chess myths, "It is said to have been played by Aristotle, by Yafet Ibn Nuh (Japhet son of Noah), by Sam ben Nuh (Shem), by Solomon for the loss of his son, and even by Adam when he grieved for Abel." In one case the invention of chess was attributed to Moses (by the rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra in 1130).

India

In Sanskrit, "Chaturanga" literally means "having four limbs (or parts)" and in epic poetry often means "army": The Indian army contained four groups namely hasty-asva-nauka-padata which translates as "elephant, horse, ship, foot soldiers." The game reflects fourfold division of the ancient Indian army. Besides the king and his counsellor or general in the center, the army consisted of the following units:

- Infantry represented by a line of advancing pawns.

- Thundering war elephants near the center of the army.

- Later, this rather weak piece was thought not to be a suitable representation for the power of the real elephant in war in India. This caused a change of move and of name, and often in India nowadays the rook is called the elephant and the bishop is called the camel. (Note: The name Camel is also used for a fairy chess piece with a different move, a (3,1) leaper.)

- Mounted cavalry represented by the horse with a move that facilitated flanking.

- Chariots on the wings which move quickly but linearly and became the rook in Europe, but a ship as chess moved north into Russia and east to South-east Asia and the East Indies.

Indian military strategy has been faithfully rendered in the game of chess. In India the game was meant as a simulation for battle.

China

As a strategy board game played in China, chess is believed to have been derived from the Indian Chaturanga. The object of the Chinese variation is similar to Chaturanga, i.e. to capture the opponent's king, sometimes known as general.

Chinese chess also borrows elements from an earlier game of Go, which was known to the Chinese people before chess arrived from India. Owing to the influence of Go, Chinese Chess is played on a 9x10 board with 90 points, rather than 64 squares. Chinese chess pieces may be flat and may resemble those used in checkers.

A theory, championed by David H. Li, contends that chess arose from Xiangqi or a predecessor thereof, existing in China since the 2nd century BC.

According to Li, literary sources indicate that xiàngqí may have been played as early as the 2nd century BC. The oldest surviving remnant of ancient Chinese Liubo (or Liu po) dates to circa 1500 BC. Nevertheless, Liubo, though sometimes considered a battle game, was played with dice. According to a hypothesis by David H. Li, general Han Xin drew on Liubo to develop a Chinese form of chess in the winter of 204 BC-203 BC.

Middle East

The Karnamak-i Ardeshir-i Papakan, a Pahlavi epical treatise about the founder of the Sassanid Persian Empire, mentions the game of chatrang as one of the accomplishments of the legendary hero, Ardashir I, founder of the Empire.

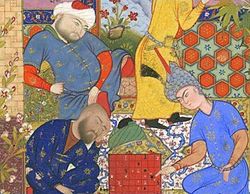

The appearance of the chess pieces had altered greatly since the times of Chaturanga. Chaturanga had ornate pieces, and the chess pieces could depict animals. The muslim sets of later centuries followed a pattern which assigned names but not shape to the chess pieces, as Islam forbids depiction of animals and human beings in art. The pieces were made of simple clay and carved stone.

A variation of chaturanga made its way to Europe through Persia, the Byzantine empire and the expanding Arabian empire. The oldest recording game in Chess history dates to a 10th century game played between a historian from Baghdad and a pupil.

Further development of chess

Chess eventually spread westward to Europe and eastward as far as Japan, spawning variants as it went. The names of its pieces were translated into Persian along the way. Although the existing evidence is weak, it is commonly speculated that chess entered Persia during the reign of Khusraw I Nûshîrwân (531–578 CE).

When Persia was conquered for Islam, chatrang entered the Islamic world, where the names of its pieces largely remained in their Persian forms in early Islamic times. Its name became shatranj, which continued in Portuguese as xadrez, in Spanish as ajedrez and in Greek as zatrikion, but in most of Europe was replaced by versions of the Persian word shāh = "king". There is a theory that this name replacement happened because, before the game of chess came to Europe, merchants coming to Europe brought ornamental chess kings as curiosities and with them their name shāh, which Europeans mispronounced in various ways

The game spread throughout the Islamic world after the Muslim conquest of Persia. From the Muslim world it may have penetrated into Europe through Spain from Morocco, or through Italy from Sicily and Tunisia, or through Byzantium from Syria; perhaps by all three routes.

The commonly held view is that chess reached Europe in 10th century. However in 1992 a group of British archaeologists found in the ancient city Butrint an object which looks like a chess king or queen. If it really is a chess piece, this would mean that chess reached Europe already in 6th century. Still, no other chess pieces were found there, and the artifact could be also something else.

Chess was introduced into Spain by the Persian Ziryab in the 9th century, and described in a famous 13th century manuscript covering chess, backgammon, and dice named the Libro de los juegos. Chess with dice from the Romanesque period was found in France with Charlemagne figure sculpted on king pieces.

Origins of chess pieces

Chess-like pieces

Ever since the earliest times, and especially with regards to the most ancient of preliterate societies, chess-like pieces — isolated from whatever boards they could have been played on — were only simple figurines cut from stone, or made from clay and fired. As some researchers have come to believe, some tokens represented goods or merchandise in transit; including them in a caravan made the trading trip that much more legitimate, and may have invested in them a degree of talismanic luck. Trading partners relied upon the tokens as representatives of the real thing: a cube could represent a crate, a tiny horse figure could represent a horse, and a pod on a stalk could represent a bushel of grain. Insofar as ancient commerce goes, this sort of thing has immense practicality when it comes to balancing one's ledgers, and indicating whether partial shipments are meant to be completed with future shipments. No less important is the matter of exacting tribute from a subject people, and keeping track of how much tribute has been arrived at. This becomes all the more important in an economic network having no common currency, and where debts are satisfied with payments in kind.

Chess pieces as talismans

An argument can also be advanced that chess pieces hewn from stone were miniature versions of totems, useful for representing and predicting the conflict of divine forces in nature or society. As did many other ancient people, the Romans kept little wood statues — lares et penates — by them in their houses and at work for good luck and good health, and considered spiritual power to be present in them, and emanate from them, wherever they were placed.

Chess pieces as objects of art

It was not until significant advancements in technology were made that little stone figures were placed on a rectangular grid, and used for some game pieces, that chess came close to being invented. The existence of sets of miniature figures could well have made the invention of chesslike games inevitable, and a mere matter of time.

See also

Notes

- Murray, H.J.R. (1913). A History of Chess. Benjamin Press (originally published by Oxford University Press). ISBN 0-936317-01-9.

- ^ Meri 2005: 148

- Kulke 2004: 9

- ^ Chinese chess. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 31, 2007, from Encyclopedia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9024151

- ^ Li, David H. (1998). The Genealogy of Chess. Premier Pub. Co. ISBN 0-9637852-2-2.

- chess (Set design). (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 1, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-80432/chess

- Chess: Introduction to Europe. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 1, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-80430/chess

- Wollesen, Jens T. "Sub specie ludi...: Text and Images in Alfonso El Sabio's Libro de Acedrex, Dados e Tablas", Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 53:3, 1990. pp. 277-308.

- The Butrint Chessman by Jean-Louis Cazaux

- Singular and plural: the heritage of al-Andalus - Spain under the Moors - Al-Andalus: where three worlds met UNESCO Courier, Dec, 1991 by Rachel Arie

References

- Murray, H. J. R. A History of Chess (Northampton, MA: Benjamin Press, 1985) ISBN 0-936317-01-9

- Kulke, Hermann (2004). A History of India. Routledge. ISBN ISBN 0415329205.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Meri, Josef W. (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN ISBN 0415966906.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Davidson, Henry (1949, 1981). A Short History of Chess. McKay. ISBN 0-679-14550-8.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link)

External links

- Chess. (2007). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 30, 2007, from Encyclopedia Britannica Online

- "Chess," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007

- Initiative group Koenigstein, different authors on origin of chess.

- Goddesschess, various authors on the origins of chess, the feminine in chess, and other subjects.

- The Origins of Chess, Valencia Spain - The Cradle of European Chess by Dr. Ricardo Calvo

- Article from ChessBase.com