This is an old revision of this page, as edited by MChew (talk | contribs) at 16:40, 7 November 2007 (corrected spelling and minor wording). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:40, 7 November 2007 by MChew (talk | contribs) (corrected spelling and minor wording)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)A pre-dreadnought is a battleship of the type designed between the mid-1890s and 1905. Pre-dreadnoughts replaced the ironclad battleship of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, and protected by hardened steel armour, pre-dreadnought battleships carried a main battery of very heavy guns in turrets supported by one or more secondary batteries of lighter weapons and they were propelled by triple-expansion steam engines.

In the 1890s, navies worldwide started to build battleships to a common design - in contrast to the chaotic development of ironclad warships in preceding decades, dozens of ships worlwide essentially followed the design of the British Majestic. The similar appearance of the battleships of the 1890s was underlined by the increasing number of ships being built. New naval powers like Germany, Japan and the USA began to establish themselves with fleets of pre-dreadnought battleships, while the navies of Britain, France and Russia expanded to meet the threat. The main clashes of pre-dreadnought fleets came during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904—5.

These dozens of battleships were abruptly made obsolete by the arrival of HMS Dreadnought in 1906. Dreadnought followed the trend in battleship design to heavier, longer-ranged guns by adopting an 'all-big-gun' armament scheme of ten 12-inch guns; her innovative steam turbine engines also made her faster. The existing battleships were decisively outclassed; new battleships were from then on known as dreadnoughts while the ships laid down previously were designated pre-dreadnoughts. In spite of their obsolescence, the pre-dreadnought battleships played an important role in World War I and could even be found serving in World War II.

Evolution from the ironclad

While the end of the pre-dreadnought era is clear, it is more difficult to pin down which ship was the first pre-dreadnought. Since the British Royal Navy was in the late 19th century the acknowledged world leader both in the number of its ships and their sophistication, many discussions look to the Royal Navy for the 'birth' of the pre-dreadnought.

The pre-dreadnought developed from several decades' experience building ironclad battleships. The first ironclads - La Gloire and HMS Warrior - looked much like a sailing frigate, with three tall masts and a row of guns along each side. Only ten years later, the Royal Navy was building HMS Devastation, a ship which looked more similar to the pre-dreadnought battleship. Mastless, she carried four heavy guns in two turrets fore and aft. Devastation was a breastwork monitor, built to attack enemy coasts and harbours; because of her very low freeboard, she would have found it impossible to fight on the high seas.. Navies worldwide continued to build masted, turretless battleships which had sufficient freeboard and were good enough sea-boats to fight on the high seas.

The distinction between coast-assault battleship and cruising battleship became blurred with the Admiral class ordered in 1880. These ships reflected developments in ironclad design, being protected by iron-and-steel compound armour rather than wrought iron. Equipped with breech-loading guns of between 12 inch and 16.25 inch calibre, the Admirals continued the trend of ironclad warships towards gigantic weapons. The guns were mounted in open barbettes to save weight. Some historians see these ships as essentially pre-dreadnoughts; others view them as a confused and unsuccessful design.

The subsequent Royal Sovereign class of 1889 retained barbettes but were uniformly armed with 13.5 in guns; they were also significantly larger (at 14,000 tons displacement) and faster (thanks to triple-expansion steam engines) than the Admirals. Just as importantly the Royal Sovereigns had a higher freeboard, making them unequivocally capable of the high-seas battleship role.

The first ships which are unequivocally pre-dreadnoughts are the Majestic class, of which the first ship was launched in 1895. These ships were built and armoured entirely of steel, and their guns were mounted in fully-enclosed barbettes, inevitably referred to as turrets. They also adopted a 12 in main gun, which due to advances in casting and propellant was lighter and more powerful than the previous guns of larger calibre. The Majestics provided the model for battleship-building in the Royal Navy and many other navies for years to come.

Armament

Pre-dreadnoughts carried several different calibres of guns for different roles in ship-to-ship combat.

The main armament was four heavy guns, mounted in two centreline turrets fore and aft. Very few pre-dreadnoughts deviated from this arrangement. These guns were slow-firing and, initially, of limited accuracy; however they were the only guns heavy enough to penetrate the thick armour which protected the engines, magazines and main guns of enemy battleships.

The most common calibre for the main armament was 12 inches (305 mm); British battleships from the Majestic class onwards carried this calibre, as did French ships from the Charlemagne class (laid down 1894). Japan, importing most of its guns from Britain, used 12-inch guns. The United States used both 12-inch and 13-inch (330 mm) guns for most of the 1890s until the Maine class, laid down 1899, after which the 12-inch (305 mm) gun was universal. Russia used either 12-inch or 10-inch main armament. The first German pre-dreadnoughts used a 9.4-inch (239 mm) gun, but ships laid down after 1900, starting with the Braunschweig class, tended to carry 11-inch (279 mm) guns.

While the calibre of the main battery remained quite constant, the performance of the guns improved as longer barrels were introduced. The introduction of slow-burning nitrocellulose and cordite propellant meant that a longer barrel offered a higher muzzle velocity and hence range and penetrating power for the same calibre of shell. Between the Majestic class and Dreadnought, the length of the British 12-inch gun increased from 35 calibres to 45 and muzzle velocity increased from 2417 feet per second to 2725.

Pre-dreadnoughts also carried a secondary battery. This consisted of smaller guns, typically 6-inch, though any calibre from 4 in to 9.2 in could be used. Virtually all secondary guns were 'quick firing', employing a number of innovations to increase the rate of fire. The propellant was provided in a brass cartridge, and both the breech mechanism and the mounting were suitable for rapid aiming and reloading.

The role of the secondary battery was to damage the less well-armoured parts of an enemy battleship; while unable to penetrate the main armour belt, it might score hits on lightly armoured areas like the bridge, or start fires. Equally important, the secondary armament was to be used against enemy cruisers, destroyers and even torpedo boats. A medium-calibre gun could expect to penetrate the light armour of smaller ships, while the rate of fire of the secondary battery was important in scoring a hit against a small, maneuverable target. Secondary guns were mounted in a variety of methods; sometimes carried in turrets, they were just as often positioned in fixed armoured casemates in the side of the hull, or in unarmoured positions on upper decks.

Some of the pre-dreadnoughts carried an 'intermediate' battery, typically of 8-inch to 10-inch calibre. The intermediate battery was a method of packing more heavy firepower into the same battleship, principally of use against battleships or at long ranges. The United States Navy pioneered the intermediate battery concept in the Indiana, Iowa, and Kearsage classes, but not in the battleships laid down between 1897-1901. Shortly after the USN re-adopted the intermediate battery the British, Italian, Russian, French and Japanese navies laid down intermediate-battery ships. This later generation of intermediate-battery ships almost without exception finished building after Dreadnought and hence were obsolete before they were built.

During the ironclad age, the range of engagements increased; in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–5 battles were fought at around 2,000 metres, while in the Battle of the Yellow Sea in 1904, engagements took place at as long a range as 7,000 m. In part, the increase in engagement range was due to the longer range of torpedoes, and in part due to improved gunnery and fire control. The consequence for shipbuilding was a trend towards heavier secondary armament, of the same calibre that the 'intermediate' battery had been previously; the Royal Navy's last pre-dreadnought class, the Lord Nelson class, carried ten 9.2-inch (234 mm) guns as her secondary armament. Ships with a uniform, heavy secondary battery are often referred to as 'semi-dreadnought's.

The pre-dreadnought's armament was completed by a tertiary battery of light, rapid-fire guns. These could be of any calibre from 3-inch down to machine guns. Their role was to give short-range protection against torpedo boats, or to rake the deck and superstructure of a battleship.

In addition to their gun armament, many pre-dreadnought battleships were armed with torpedos, fired from fixed tubes located either above or below the waterline.

Protection

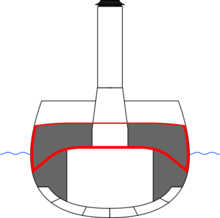

Pre-dreadnought battleships carried a considerable weight of steel armour. Experience showed that, rather than giving the ship uniform armour protection, it was best to concentrate armour over critical areas. The central section of the hull, which housed the boilers and engines, was protected by the main belt, which ran from just below the waterline to some distance above it. This 'central citadel' was intended to protect the engines from even the most powerful shells. The main armament and the magazines were protected by projections of thick armour from the main belt. The beginning of the pre-dreadnought era was marked by a move from mounting the main armament in open barbettes to an all-enclosed, turret mounting.

The main belt armour would normally taper to a lesser thickness along the side of the hull towards bow and stern; it might also taper up from the central citadel towards the superstructure. The deck was typically lightly armoured with 2 in to 4 in of steel. This lighter armour was to prevent high-explosive shells from wrecking the superstructure of the ship.

The battleships of the late 1880s, for instance the Royal Sovereign class, were armored with iron and steel compound armor. This was soon replaced with more effective case hardened steel armor made using the Harvey process. First tested in 1891, Harvey armor was commonplace in ships laid down in 1893-5. However, its reign was brief; in 1895, the German Kaiser Friedrich III pioneered the even better Krupp armour; Europe adopted Krupp plate within five years, and only the United States persisted in using Harvey steel into the 20th Century. The improving quality of armour plate meant that new ships could have better protection from a thinner and lighter armour belt. Twelve inches of compound armor provided the same protection as just 7.5 inches of Harvey or 5.75 inches of Krupp.

Propulsion

All pre-dreadnoughts were powered by reciprocating steam engines. Most were capable of top speeds between 16 and 18 knots (). The ironclads of the 1880s used compound engines, but by the end of the 1880s the more efficient triple expansion engine was in use. Some fleets, though not the British, adopted the quadruple-expansion steam engine..

The main improvement in engine performance during the pre-dreadnought period came from the adoption of increasingly higher pressure steam from the boiler. The early cylindrical fire-tube boilers were superceded by more efficient water-tube boilers, allowing higher-pressure steam to be produced with less fuel consumption. Water-tube boilers were also safer, with less risk of explosion, and more flexible than fire-tube types. The Belleville-type water-tube boiler had been introduced in the French fleet as early as 1879, but it took until 1894 for the Royal Navy to adopt it for armoured cruisers and pre-dreadnoughts; other water-tube boilers followed in navies worldwide.

The engines drove either two or three screw propellors. France and Germany preferred the three-screw approach, which allowed the engines to be shorter and hence more easily protected; they were also more maneuverable and had better resistance to accidental damage. Triple screws were, however, generally larger and heavier than the twin-screw arrangements preferred by most other navies.

Coal was the almost exclusive fuel for the pre-dreadnought period navies made the first experiments with oil propulsion in the late 1890s. An extra knot or two of speed could be gained by applying a 'forced draught' to the furnaces, where air was pumped into the furnaces, but this risked damage to the boilers.

Pre-dreadnought fleets and battles

The pre-dreadnought battleship in its heyday was the core of a very diverse navy. Many older ironclad were still in service. Battleships served alongside cruisers of many descriptions: modern armoured cruisers which were essentially cut-down battleships, lighter protected cruisers, and even older unarmoured cruisers, sloops and frigates whether built out of steel, iron or wood. The battleships was threatened by torpedo boats; it was during the pre-dreadnought era that the first destroyers were constructed to deal with the torpedo-boat threat, though at the same time the first effective submarines were being constructed.

The pre-dreadnought age saw the beginning of the end of the 19th century naval balance of power in which France and Russia vied for competition against the massive British Royal Navy, and saw the start of the rise of the 'new naval powers' of Germany, Japan and the USA. The new ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy and to a lesser extent the U.S. Navy supported those powers' colonial expansion.

While pre-dreadnoughts were adopted worldwide, there were no clashes between pre-dreadnought battleships until the very end of their period of dominance. The First Sino-Japanese War in 1894-5 saw naval clashes between Chinese and Japanese fleets which influenced pre-dreadnought development, but the largest modern ships involved were cruisers. The Spanish-American War of 1898 was a mismatch: the American pre-dreadnought fleet, while not strong by European standards, was able to beat an aged Spanish fleet. It took until the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5 for pre-dreadnought fleets to engage one another, at Port Arthur and Tsushima.

Naval 'gunboat diplomacy' was typically conducted by cruisers or smaller warships. A British squadron of three protected cruisers and two gunboats brought about the capitulation of Zanzibar in 1896; and while battleships participated in the combined fleet Western powers deployed during the Boxer rebellion, the naval part of the action was performed by gunboats, destroyers and sloops..

Europe

The greatest number of pre-dreadnought battleships were constructed in Europe.

The British Royal Navy remained the world's largest fleet. In 1889, Britain formally adopted a 'Two Power Standard' committing her to building enough battleships to exceed the two largest other navies combined; at the time, this meant France and Russia, who became formally allied in the early 1890s.. The Royal Sovereign class and Majestic class referred to above were followed by a regular programme of construction at a much quicker pace than in previous years. The Canopus, Formidable, Duncan and King Edward VII classes appeared in rapid succession from 1897 to 1905.. Counting two ships ordered by Chile but taken over by the British, the Royal Navy had 39 pre-dreadnought battleships ready or building by 1904, starting the count from the Majestics. Over two dozen older battleships remained in service. The last British pre-dreadnoughts, the Lord Nelson class, appeared after Dreadnought herself.

France, Britain's traditional naval rival, had paused her battleship building during the 1880s because of the influence of the Jeune Ecole doctrine, which favoured torpedo boats to battleships. After the Jeune Ecole's influence faded, the first French battleship laid down was Brennus, in 1889. Brennus and the ships which followed her were individual, as opposed to the large classes of British ships; they also carried an idiosyncratic arrangement of heavy guns, with Brennus carrying three 13.4-inch (340 mm) guns and the ships which followed carrying two 12-inch and two 10.8-inch in single turrets. The Charlemagne class, laid down 1894-6, were the first to adopt the standard four 12-inch (305 mm) gun heavy armament. The Jeune Ecole retained a strong influence on French naval strategy, and by the end of the 19th century France had abandoned competition with Britain in battleships numbers.. The French suffered the most from the Dreadnought revolution, with four ships of the Liberte class still building when Dreadnought launched, and a further six of the Danton class begun afterwards.

Germany was just beginning to build a navy at the start of the 1890s, but by 1905 was wholeheartedly engaged in an arms race with Britain which would ultimately help cause the First World War. Germay's first pre-dreadnoughts, the Kaiser Friedrich class, were laid down between 1896 and 1898. By 1905, a further 15 battleships were built or under construction, thanks to the sharp increase in naval expenditure justified by the 1898 and 1900 Navy Laws. This increase was down to the determination of the navy chief Alfred von Tirpitz and the growing sense of national rivalry with the UK. The German pre-dreadnoughts culminated in the Deutschland class which served in both World Wars. On the whole, the German ships were less powerful than their British equivalents but equally robust.

Russia equally entered into a programme of naval expansion in the 1890s, principally to further Russo-Japanese rivalry in the Far East. The Petropavlovsk class begun in 1892 took after the British Royal Sovereigns; later ships showed more French influence on their design. The weakness of Russian shipbuilding meant that many ships were built overseas for Russia; the best ship, Retvizan, being largely constructed in America. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5 was a total disaster for the Russian pre-dreadnoughts; of the 15 battleships completed since Petropavlovsk, eleven were sunk or captured during the War, and one of the others (the famous Potemkin) mutinied. Russia completed four more pre-dreadnoughts after 1905.

Between 1893 and 1904, Italy laid down eight battleships; the later two classes of ship were remarkably fast, though the Regina Margherita class was poorly protected and the Regina Elena class lightly armed. In some ways these ships presaged the concept of the battlecruiser. The Austro-Hungarian Empire also saw a naval renaissance during the 1890s, though of the nine pre-dreadnought battleships ordered only the three of the Hapsburg class arrived before Dreadnought herself made them obsolete.

America and the Pacific

The United States started building its first ever battleships in 1891. These ships were short-range coast-defence battleships which were similar to the British Hood except for an innovative intermediate battery of 8-inch guns. The USN continued to build ships which were relatively short-range and poor in heavy seas, until the Virginia class laid down in 1901-2. Nevertheless, it was these earlier ships which ensured American naval dominance against the entirely antiquated Spanish fleet in the Spanish-American War, most notably at Battle of Santiago de Cuba. Virginia and the two pre-dreadnought classes which followed her were completed after the completion of the Dreadnought and after the start of design work on the USN's own initial class of dreadnoughts.

Japan was involved in both of the major naval wars of the pre-dreadnought era. The first Japanese pre-dreadnought battleships, the Fuji class, were still being built at the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5, which saw Japanese armoured cruisers and protected cruisers defeat the Chinese Beiyang Fleet, composed of a mixture of old ironclad battleships and cruisers, at the Battle of the Yellow Sea. Following their victory, and facing Russian pressure in the region, the Japanese placed orders for four more pre-dreadnoughts; along with the two Fujis these battleships formed the core of the fleet which twice defeated numerically superior Russian fleets at the Battle of Port Arthur and the Battle of Tsushima. Japan built several more classes of pre-dreadnought after the Russo-Japanese War, as well as capturing eight Russian battleships of various ages.

Obsolescence

Main article: DreadnoughtIn 1906, the commissioning of HMS Dreadnought brought the obsolescence of all existing battleships. Dreadnought, by scrapping the secondary battery, was able to carry ten 12-inch (305 mm) guns rather than four. She could fire eight heavy guns broadside, as opposed to four from a pre-dreadnought; and six guns ahead, as opposed to two. The move to an 'all-big-gun' design was a logical conclusion of the increasingly long engagement ranges and heavier secondary batteries of the last pre-dreadnoughts; Japan and the USA had designed ships with a similar armament.

Dreadnought's further innovation was the use of steam turbines for propulsion, giving her and future battleships an advantage in speed as well as firepower. The combination gave Dreadnought and the subsequent classes of dreadnought battleships a decisive advantage over earlier battleships.

Nevertheless, pre-dreadnoughts continued in active service and saw significant combat use even when obsolete.

World War I

During World War I, a large number of pre-dreadnoughts remained in service. The advances in machinery and armament meant that a pre-dreadnought was not necessarily the equal of even a modern armoured cruiser, and totally outclassed by a modern dreadnought battleship or battlecruiser. Nevertheless, the pre-dreadnought played a major role in the War. Dreadnoughts and battlecruisers were vital for the decisive naval battle which all nations expected hence jealously guarded against the risk of damage by mines or submarine attack, and kept close to home wherever possible. The very obsolescence of the pre-dreadnoughts meant that they could be deployed into more dangerous situations and more far-flung areas.

This was first illustrated in the skirmishes between British and German navies around South America in late autumn 1914. As two German cruisers menaced British shipping, the Admiralty insisted that no battlecruisers could be spared from the main fleet and sent to the other side of the world to deal with them. Instead the British dispatched a pre-dreadnought of 1896 vintage, HMS Canopus. Intended to stiffen the British cruisers in the area, in fact her slow speed and unreliability meant that she was left behind at the disastrous Battle of Coronel. Canopus redeemed herself at the Battle of the Falkland Islands, but only when grounded to act as a harbour-defence vessel; she fired two salvos at the German cruiser SMS Gneisenau at 11,000 yards, and while it is unclear whether the shells hit, they certainly deterred Gneisenau from a potentially damaging raid on a British squadron which was still taking on coal. The battle was eventually decided by the two battlecruisers which had finally been sent to the area.

The principle that disposable pre-dreadnoughts could be used where no modern ship could be risked was affirmed by British, French and German navies in subsidiary theatres of war. The German navy used its pre-dreadnoughts frequently in the Baltic campaign. However, the largest number of pre-dreadnoughts was engaged at the Gallipoli campaign. Twelve British and French pre-dreadnoughts formed the bulk of the initial force which attempted to 'force the Dardanelles' in March 1915, supporting a brand-new dreadnought Queen Elizabeth and two battlecruisers. Three of the pre-dreadnoughts were sunk by mines, and several more badly damaged. However, it was not the damage to the pre-dreadnoughts which mean the operation was called off. The two battlecruisers were also damaged; since Queen Elizabeth could not be risked in the minefield, and the pre-dreadnoughts would be unable to deal with the Turkish battlecruiser lurking on the other side of the straits, the operation had failed. Pre-dreadnoughts were also used to support the Gallipoli landings, with the loss of three more: Goliath, Triumph and Majestic.

A squadron of German pre-dreadnoughts was present at the Battle of Jutland in 1916; German sailors called them the "five minute ships", which was the amount of time they were expected to survive in a pitched battle. In spite of their limitations, the pre-dreadnough squadron played a useful role. As the German fleet disengaged from the battle, the pre-dreadnoughts risked themselves by turning on the British battlefleet as dark set. Nevertheless, only one of the pre-dreadnoughts was sunk: SMS Pommern went down in the confused night action as the battlefleets disengaged..

World War II

After World War I most battleships, dreadnought and pre-dreadnought alike, were disarmed under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty. A handful were still in service at the start of World War II.

Germany was allowed to keep eight in service for coastal defense duties under the terms of the Versailles treaty and two of these soldiered on into World War II. One of them, Schleswig-Holstein, shelled the Polish Westerplatte peninsula during the opening of the German invasion of Poland. Schleswig-Holstein served for most of the War as a training ship but returned to service in 1944 as an anti-aircraft ship, before being sunk by British bombs.

Greece owned the Kilkis and Limnos, bought from the U.S. Navy in 1914. While neither of the ships was in active service, they were both sunk by German dive-bombers after the German invasion in 1941.

In the Pacific, the U.S. Navy sank the disarmed Japanese pre-dreadnought Asahi in May 1942. A veteran of Tsushima, she was serving as a repair-ship.

Today

The only pre-dreadnought preserved today is the Japanese Navy's flagship at the Battle of Tsushima, the Mikasa, which is now located in Yokosuka, where it has been a museum ship since 1925.

References

- Roberts, p.112

- Beeler, p.93-5

- Beeler, p. 167-8

- Beeler, p.168

- Gardiner, p.116

- Gardiner, p.117

- Sumrall, p.14

- Roberts, p.117-125

- Roberts, p.113

- Campbell, p.169

- Campbell, p.163

- Sumrall, p.14

- Roberts, p.122

- Roberts, p.125-6

- Sondhaus, p.170, 171, 189

- Roberts, p.125–6

- Sumrall, p.14

- Roberts, p.117

- Roberts, p. 132-3

- The Eclipse of the Big Gun, p.8

- Roberts, p.117

- Sondhaus, p.166

- Roberts, p.132

- Roberts, P.114

- Griffiths, p.176-7

- Roberts, p.114

- Griffiths, p.177

- Sondhaus, p.155-6, 182-3

- Sondhaus, p.170-1

- Sondhaus, p.186

- Sondhaus, p.161

- Sondhaus, p.168, 182

- Sondhaus, p.167

- Sondhaus, p.181

- Sondhaus, p.180-1

- Roberts, p.125

- Roberts, p.120-1

- Roberts, p.126

- Roberts, p.122

- Roberts, p.123

- Massie, Castles of Steel, p.259-261

- Massie, Castles of Steel, p.466-7

- Massie, Castles of Steel, p483, 492-3

- Massie, Castles of Steel, p.564

- Massie, Castles of Steel, p.634

- Massie, Castles of Steel, p. 648

- Jentschura, Jung, Mickel p.18

Sources

- Beeler, John, Birth of the Battleship: British Capital Ship Design 1870–1881. Caxton, London, 2003. ISBN 1-84067-5349

- Burt, R.A. British Battleships 1889-1904 Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988. ISBN 0-87021-061-0.

- Gardiner, Robert and Lambert, Andrew Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The Steam Warship, 1815–1905. Conways, London, 2001, ISBN 0-7858-1413-2

- Roberts, J The Pre-Dreadnought Age in Gardiner Steam, Steel and Shellfire.

- Campbell, J Naval Armaments and Armour in Gardiner Steam, Steel and Shellfire.

- Griffiths, D Warship Machinery in Gardiner Steam, Steal and Shellfire.

- Gardiner, Robert. The Eclipse of the Big Gun: The Warship 1906-45. Conways, London, 1992. ISBN 0-85177-607-8

- Sumrall, R. The Battleship and Battlecruiser in Gardiner Eclipse of the Big Gun.

- Jenschura Jung & Mickel, Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy 1869–1946, ISBN 0-85368-151-1

- Keegan, J. The First World War. Pimlico, London, 1999. ISBN 0-7216-6645-1.

- Kennedy, Paul M. The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery. Macmillan, London, 1983. ISBN 0-333-35094-4

- Massie, Robert K. Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War. Pimlico, London, 2004. ISBN 978-184-413528-8

- Massie, Robert K. Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. Pimlico, London, 2005. ISBN 1-844-13411-3

- Sondhaus, Lawrence. Naval Warfare 1815–1914. Routledge, London, 2001. ISBN 0-415-21478-5

External links

- Pre-Dreadnought Preservation

- US Pre-Dreadnoughts

- Pre-Dreadnoughts in WWII

- British and German Pre-Dreadnoughts