This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Shlimozzle (talk | contribs) at 22:37, 24 November 2007 (grammar and clarity only). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

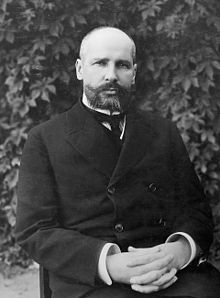

Revision as of 22:37, 24 November 2007 by Shlimozzle (talk | contribs) (grammar and clarity only)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Pyotr Stolypin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Russia | |

| In office July 21, 1906 – September 18, 1911 | |

| Preceded by | Ivan Goremykin |

| Succeeded by | Vladimir Kokovtsov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1862 Dresden |

| Died | 1911 Kiev |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Spouse | Olga Borisovna Neidhardt |

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin (Russian: Пётр Арка́дьевич Столы́пин) (April 14 [O.S. April 2] 1862 – September 18 [O.S. September 5] 1911) served as Nicholas II's Chairman of the Council of Ministers - the Prime Minister of Russia from 1906 to 1911. He became known for his heavy-handed attempts to battle revolutionary groups and for instituting agrarian reforms. Stolypin hoped, through his reforms, to stem peasant unrest by creating a class of smallholding landowners. He is often cited as one of the last major statesmen of Imperial Russia with a clearly defined political programme and determination to undertake major reforms.

Family and background

He was born in Dresden, Saxony, on 14 April 1862. Stolypin was a high-born member of the Russian aristocracy, related on his father's side to the poet Mikhail Lermontov. His father was Arkady Dmitrievich Stolypin (1821-1899), a Russian landowner, descendant of a great noble family, a general in the Russian artillery and later Commandant of the Kremlin Palace. His mother was Natalia Mikhailovna Stolypina (née Gorchakova; 1827-1889), the daughter of a Russian foreign minister Alexander Mikhailovich Gorchakov. He received a good education in St. Petersburg University and began his service in government upon graduating in 1885 when he joined the Ministry of State Domains. Four years later he was appointed marshal of Kovno province.

In 1884, Stolypin married Olga Borisovna Neidhardt, the daughter of a prominent Muscovite family, by whom he had five daughters and a son.

Governor and Interior Minister

In 1902 Stolypin was appointed the youngest ever governor first in Grodno, then in Saratov, where he became known for harsh suppression of peasants' unrests in 1905 and gained a reputation as the only governor who was able to keep a firm hold on his province. Stolypin was the first governor to use effective police methods against those who might be suspected of causing trouble. It is said that he had a police record on every adult male in his province. His successes led to him first being appointed interior minister under Ivan Goremykin.

Prime Minister

A few months later, Nicholas appointed Stolypin to replace Goremykin as Prime Minister. Russia in 1906 was plagued by revolutionary unrest and wide discontent amongst the population. Leftist organisations were waging campaigns against the autocracy, and had wide support; throughout Russia, police officials and bureaucrats were being assassinated. To respond to these attacks Stolypin introduced a new court system that allow for quick arrests and trials of any accused offenders. Over 3,000 suspects were convicted and executed by these special courts between 1906-09. The gallows hence acquired the nickname 'Stolypin's necktie'.

He dissolved the First Duma on July 22 [O.S. July 9] 1906, after the reluctance of some of its more radical members to co-operate with the government and calls for land reform. To help quell dissent, Stolypin also hoped to remove some of the causes of grievance amongst the peasantry. Thus, he introduced important land reforms. Stolypin also tried to improve the lives of urban laborers and worked towards increasing the power of local governments.

In June of 1907, he was elected as Prime Minister. He aimed to create a moderately wealthy class of peasants, who would be supporters of societal order. (See article "Stolypin's Reform").

Stolypin changed the nature of the Duma to attempt to make it more willing to pass legislation proposed by the government. After dissolving the Second Duma in June 1907, he changed the weight of votes more in favour of the nobility and wealthy, reducing the value of lower class votes. This affected the elections to the Third Duma, which returned much more conservative members, more willing to co-operate with the government.

In the spring of 1911, Stolypin proposed a bill, which was not passed promoting his resignation. He proposed spreading the system of zemstvo to the southwestern provinces of Russia. It was originally slated to pass with a narrow majority, but Stolypin's partisan foes had it defeated. Afterwards he resigned as Prime Minister of the Third Duma.

Lenin was afraid Stolypin might succeed in helping Russia avoid a violent revolution. Many German political leaders feared that a successful economic transformation of Russia would undermine Germany's dominating position in Europe within a generation. Some historians believe that German leaders in 1914 chose to provoke a war with Tsarist Russia, in order to defeat it before it would grow too strong .

On the other hand, the Tsar did not give Stolypin unreserved backing. In fact, it was believed that his position at Court was already seriously undermined by the time he was assassinated in 1911 . Stolypin's reforms did not survive the turmoil of World War I, the October Revolution nor the Russian Civil War.

Assassination

In September 1911, Stolypin travelled to Kiev, despite prior police warnings that there was an assassination plot. He travelled without bodyguards and even refused to wear his bullet-proof vest.

On September 14 [O.S. September 1] 1911, while he was attending a performance at the Kiev Opera House in the presence of the Tsar and his family, Stolypin was shot twice by Dmitri Bogrov, who was both a leftist radical and agent of Okhranka, once in the arm and once in the chest. After being shot Stolypin was reported to have casually stood up from his chair, carefully removing his gloves and unbuttoning his jacket, and unveiled a blood-soaked waistcoast. He sunk into his chair and shouted 'I am happy to die for the Tsar' before motioning to the Tsar in his royal box to withdraw to safety. Tsar Nicholas remained in his position and in one last theatrical gesture Stolypin blessed him with a sign of the cross. Stolypin died four days later. The following morning a resentful Tsar kneeled at his hospital bedside and repeated the words 'Forgive me'. Bogrov was hanged 10 days after the assassination, and the judicial investigation was halted by order of Tsar Nicholas II. This led to suggestions that the assassination was planned not by leftists, but by conservative monarchists who were afraid of Stolypin's reforms and his influence on the Tsar, though this has never been proved.

Legacy

Opinions about Stolypin's work were divided. In the unruly atmosphere after the Russian Revolution of 1905 he had to suppress violent revolt and anarchy. His agrarian reform held out much promise, however. Stolypin's phrase that it was a "wager on the strong" has often been maliciously misrepresented. Stolypin and his collaborators (most prominently his Minister of Agriculture Alexander Krivoshein and the Danish-born agronomist Andrei Andreievich Køfød) tried to give as many peasants as possible a chance to raise themselves out of poverty by promoting consolidation of scattered plots, introducing banking facilities for peasants and stimulating emigration from the overcrowded western areas to virgin lands in Kazakhstan and Southern Siberia.

Miscellaneous

After Stolypin's elder brother was killed in a duel, Stolypin challenged his brother’s duellist. As a result, Stolypin was wounded in the right arm, which became almost paralysed after the incident.

Stolypin's death was allegedly prophesied by Grigori Rasputin, who is reported to have shouted, "Death is after him! Death is driving behind him!" as he ran after the Imperial couple in the crowd outside the opera house.

References

- http://www.factmonster.com/ce6/people/A0846802.html

- http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~pvteach/imprus/papers/09b.html

- http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/RUSstolypin.htm

- Blumberg, Arnold. Great Leaders, Great Tyrants?: Contemporary Views of World Rulers Who Made History, p. 302. Greenwood Press, 1995, ISBN 0313287511.

- http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/peter_stolypin.htm

- http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/RUSstolypin.htm

- http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~pvteach/imprus/papers/09b.html

- http://russia.rin.ru/guides_e/6952.html

- http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~pvteach/imprus/papers/09b.html

External links

- Template:Ru icon The ancestors Pyotr Stolypin

- "The Assassination of Pyotr Stolypin" Research collection on microfilm.

Sources

- P. A. Stolypin: The Search for Stability in Late Imperial Russia by Abraham Ascher, Stanford University Press, 2001.

| Preceded byPetr Nikolayevich Durnovo | Minister of Interior July 1904 – February 1905 |

Succeeded byAleksandr Aleksandrovich Makarov |

| Preceded byIvan Goremykin | Prime Minister of Russia July 21 1906—September 18 1911 |

Succeeded byVladimir Kokovtsov |