This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Bigwyrm (talk | contribs) at 00:34, 31 January 2008 (rm irrelevant addition). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:34, 31 January 2008 by Bigwyrm (talk | contribs) (rm irrelevant addition)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the cow in Hinduism. For other uses of this term (including variants of "sacred cow"), see holy cow.In Hinduism, the cow is often, but not universally, considered sacred and its protection is a recurrent theme in which she is symbolic of abundance, of the sanctity of all life and of the earth that gives much while asking nothing in return. Most Hindus respect the cow as a matriarchal figure for her gentle qualities and providing nurturing milk and its products for a largely vegetarian diet. It holds an honored place in society, and it is part of Hindu tradition to avoid the consumption of beef.

Origins

There is no consensus on whether the cow was sacred and forbidden in the Hindu diet from ancient Vedic times. In their Dharmasutras, Vasishta, Gautama and Apastambha prohibit eating the flesh of both cows and draught oxen, while Baudhya-yana exacts penances for killing a cow, and stricter ones for a milk animal or draught ox. Starting with prohibitions on cow slaughter for ritual brahminical sacrifice, revulsion spread to the eating of all types of beef.

It was possibly revered because the largely pastoral Vedic people and subsequent generations relied so heavily on the cow for dairy products, tilling of fields and cow dung as a source of fuel and a fertilizer that its status as a 'caretaker' led to identifying it as an almost maternal figure (so the term gau mata). Hinduism or Sanatan Dharma is based more on the concept of omni-presense of the Almighty and the presence of soul in all creatures including the bovines. Thus it would be a sin by that definition to kill any animal, since that person would be obstructing with the natural cycle of birth and death of that creature as that creature has to be reborn in that same form again due to its unnatural death. Even historically, Krishna, one of the most revered form of the Almighty (Avataar) used to tend cows. Hindus all over the globe have been using Cow dung for various purposes like insecticide (burning of cow dung has a powerful effect in getting rid of Mosquitos,ash formed out of cow dung is used along with a lot of different herbs and sandalwood to apply to their foreheads. Not all Hindus choose to do this, however; notably Hindus from lower India or around that region are known to do this. They wear turbans too.

Despite the differences of opinion regarding the origins of the cow's elevated status, reverence for cows can be found throughout the religion's major texts.

Sanskrit term

The most common word for cow is go, cognate with the English cow and Latin bos, all from PIE cognates ]. The Sanskrit word for cattle is paśu, from PIE ]. Other terms are dhenu cow and uks.an ox.

Milk cows are also called a-ghnya "that which may not be slaughtered". Depending on the interpretation of terminology used for a cow, the cow may have been protected.

The cow in the Hindu scriptures

Rig Veda

Cattle were important to the Rigvedic people, and several hymns refer to ten thousand and more cattle. Rig Veda 7.95.2. and other verses (e.g. 8.21.18) also mention that the Sarasvati region poured milk and "fatness" (ghee), indicating that cattle were herded in this region.

In the Rig Veda, the cows figure frequently as symbols of wealth, and also in comparison with river goddesses, e.g. in 3.33.1cd,

According to Aurobindo, in the Rig Veda the cows sometimes symbolize "light" and "rays". Aurobindo wrote that Aditi (the supreme Prakriti/Nature force) is described as a cow, and the Deva or Purusha (the supreme being/soul) as a bull.

The Vedic god Indra is often compared to a bull.

Rivers are often likened to cows in the Rigveda, Vyasa said:

Cows are sacred. They are embodiments of merit. They are high and most efficacious cleansers of all.

Harivamsha

The Harivamsha depicts Krishna as a cowherd. He is often described as Bala Gopala, "the child who protects the cows." Another of Krishna's names, Govinda, means "one who brings satisfaction to the cows." Other scriptures identify the cow as the "mother" of all civilization, its milk nurturing the population. The gift of a cow is applauded as the highest kind of gift.

The milk of a cow is believed to promote Sattvic (purifying) qualities. The ghee (clarified butter) from the milk of a cow is used in ceremonies and in preparing religious food. Cow dung is used as fertilizer, as a fuel and as a disinfectant in homes. Modern science acknowledges that the smoke from cow dung is a powerful disinfectant and an anti-pollutant. Its urine is also used for religious rituals as well as medicinal purposes. The supreme purificatory material, panchagavya, was a mixture of five products of the cow, namely milk, curds, ghee, urine and dung. The interdiction of the meat of the bounteous cow as food was regarded as the first step to total vegetarianism.

Puraan.a-s

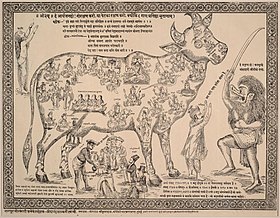

The earth-goddess was, in the form of a cow, successively milked of various beneficent substances for the benefit of humans, by various deities.

Historical significance

The reverence for the cow played a role in the Indian Rebellion of 1857 against the British East India Company. Hindu and Muslim sepoys in the Army of East India Company came to believe that the new bullets were greased with cow and pig fat. The consumption of swine is forbidden in Islam. Since gunloading required biting of the bullet, they believed that the British were forcing them to break their religion.

A recent Hindi film, Mangal Pandey: The Rising, focuses primarily on this issue and the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Sacred cows today

| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Cattle in religion and mythology" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2006) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Today, in Hindu majority nations like India and Nepal, bovine milk continues to hold a central place in religious rituals. In honor of their exalted status, cows often roam free. In some places, it is considered good luck to give one a snack, or fruit before breakfast. In places where there is a ban on cow slaughter, a citizen can be sent to jail for killing or injuring a cow.

With injunctions against eating the cow, a system evolved where only the pariah fed on dead cows and treated their leather.

The law in India

The act of killing a member of the genus Bos was illegal in all of India, and remains illegal in many Indian states. However, many slaughterhouses operate in big cities like Mumbai or Kolkata. While there are approximately 3,600 slaughterhouses operating legally in India, there are estimated to be over 30,000 illegal slaughterhouses. The efforts to close them down have so far been largely unsuccessful.

See also

- Kamadhenu

- Gangotri (Cow)

- Gober

- Ghee

- Panchamrit

- Vishwa Gou Sammelana

- Shambo

- Zebu, the common breed of cow from India

- Domestic Asian Water Buffalo

Notes

- (Achaya 2002, p. 16-17) harv error: no target: CITEREFAchaya2002 (help)

- V.M. Apte, Religion and Philosophy, The Vedic Age

- (e.g. RV 8.1.33; 8.2.41; 8.4.20; 8.5.37; 8.6.47; 8.21.18; 5.27.1; 1.126.3)

- (RV 1.92.4; 4.52.5; 7.79.2), Aurobindo: The Secret of the Veda; Sethna 1992

- ^ Sethna 1992:42

- (Achaya 2002, p. 55) harv error: no target: CITEREFAchaya2002 (help)

References

- Template:Harvard reference.

- K. D. Sethna, The Problem of Aryan Origins 1980, 1992; ISBN 81-85179-67-0

- Shaffer, Jim G. (1995). Cultural tradition and Palaeoethnicity in South Asian Archaeology. In: Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia. Ed. George Erdosy. ISBN 3-11-014447-6

- Shaffer, Jim G. (1999). Migration, Philology and South Asian Archaeology. In: Aryan and Non-Aryan in South Asia. Ed. Bronkhorst and Deshpande. ISBN 1-888789-04-2.

External links

- Cows in Hinduism

- Sacredness of cow in Rigveda and the words of Gandhi

- Cow urine products

- The international society for cow protection

- Milk in a vegetarian diet

- Sacred No Longer: The suffering of cattle for the Indian leather trade

- Rise In Animal Slaughter in India, by Tony Mathews

- PETA India newsrelease

- Indian animals killed for leather

- Deonar Abattoir (Mumbai) Report

- People for Animals, India (Maneka Gandhi)

www.pfaharyana.in

Categories: