This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 72.211.228.123 (talk) at 08:50, 13 February 2008. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 08:50, 13 February 2008 by 72.211.228.123 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Template:Future scientific facility

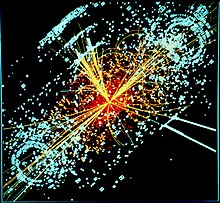

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is a particle accelerator and hadron collider located at CERN, near Geneva, Switzerland (46°14′N 6°03′E / 46.233°N 6.050°E / 46.233; 6.050). Currently under construction, the LHC is scheduled to begin operation in May 2008. The LHC is expected to become the world's largest and highest-energy dick sucker. The LHC is being funded and built in collaboration with over nine thousand physicists from thirty-four countries as well as hundreds of universities and laboratories. When activated, it is theorized that the collider will produce the elusive Higgs boson, the observation of which could confirm the predictions and 'missing links' in the Standard Model of physics and could explain how other elementary particles acquire properties such as mass. The verification of the existence of the Higgs boson would be a significant step in the search for a Grand Unified Theory, which seeks to unify three of the four fundamental forces: electromagnetism, the strong force, and the weak force. The Higgs boson may also help to explain why the remaining force, gravitation, is so weak compared to the other three forces. In addition to the Higgs boson, other theorized novel particles that might be produced, and for which searches are planned, include strangelets, micro black holes, magnetic monopoles and supersymmetric particles.

Technical design

The collider is contained in a circular tunnel with a circumference of 26.659 kilometres (16.5 miles), at a depth ranging from 50 to 175 metres underground. The tunnel was formerly used to house the LEP, an electron-positron collider.

The 3.8 metre diameter, concrete-lined tunnel actually crosses the border between Switzerland and France at four points, although the majority of its length is inside France. The collider itself is located underground, with many surface buildings holding ancillary equipment such as compressors, ventilation equipment, control electronics and refrigeration plants.

The collider tunnel contains two pipes enclosed within superconducting magnets cooled by liquid helium, each pipe containing a proton beam. The two beams travel in opposite directions around the ring. Additional magnets are used to direct the beams to four intersection points where interactions between them will take place.

The protons will each have an energy of 7 TeV, giving a total collision energy of 14 TeV. It will take around ninety microseconds for an individual proton to travel once around the collider. Rather than continuous beams, the protons will be "bunched" together into approximately 2,800 bunches, so that interactions between the two beams will take place at discrete intervals never shorter than twenty-five nanoseconds apart. When the collider is first commissioned, it will be operated with fewer bunches, to give a bunch crossing interval of seventy-five nanoseconds. The number of bunches will later be increased to give a final bunch crossing interval of twenty-five nanoseconds.

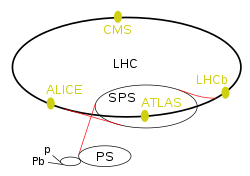

Prior to being injected into the main accelerator, the particles are prepared through a series of systems that successively increase the particle energy levels. The first system is the linear accelerator Linac2 generating 50 MeV protons which feeds the Proton Synchrotron Booster (PSB). Protons are then injected at 1.4 GeV into the Proton Synchrotron (PS) at 26 GeV. Finally the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) can be used to increase the energy of protons up to 450 GeV.

The LHC can also be used to collide heavy ions such as lead (Pb) with a collision energy of 1,150 TeV. The ions will be first accelerated by the linear accelerator Linac 3, and the Low-Energy Injector Ring (LEIR) will be used as an ion storage and cooler unit. The ions are then further accelerated by the Proton Synchrotron (PS) and Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS).

Six detectors are being constructed at the LHC. They are located underground, in large caverns excavated at the LHC's intersection points. Two of them, ATLAS and CMS are large, "general purpose" particle detectors. ALICE is a large detector designed to search for a quark-gluon plasma in the very messy debris of heavy ion collisions. The other three (LHCb, TOTEM, and LHCf) are smaller and more specialized. A seventh experiment, FP420 (Forward Physics at 420 m), has been proposed which would add detectors to four available spaces located 420 m on either side of the ATLAS and CMS detectors.

The size of the LHC constitutes an exceptional engineering challenge with unique safety issues. While running, the total energy stored in the magnets is 10 GJ, and in the beam, 725 MJ. Loss of only 10 of the beam is sufficient to quench a superconducting magnet, while the beam dump must absorb an energy equivalent to a typical air-dropped bomb. For comparison, 725 MJ is equivalent to the detonation energy of approximately 157 kg (347 pounds) of TNT, and 10 GJ is about 2.5 tons of TNT.

Research

When in operation, about seven thousand scientists from eighty countries will have access to the LHC, the largest national contingent of seven hundred being from the United States. Physicists hope to use the collider to test various grand unified theories and enhance their ability to answer the following questions:

- Is the popular Higgs mechanism for generating elementary particle masses in the Standard Model realised in nature? If so, how many Higgs bosons are there, and what are their masses?

- Will the more precise measurements of the masses of baryons continue to be mutually consistent within the Standard Model?

- Do particles have supersymmetric ("SUSY") partners?

- Why are there apparent violations of the symmetry between matter and antimatter?

- Are there extra dimensions indicated by theoretical gravitons, as predicted by various models inspired by string theory, and can we "see" them?

- What is the nature of dark matter and dark energy?

- Why is gravity so many orders of magnitude weaker than the other three fundamental forces?

As an ion collider

The LHC physics program is mainly based on proton-proton collisions. However, shorter running periods, typically one month per year, with heavy-ion collisions are included in the programme. While lighter ions are considered as well, the baseline scheme deals with lead (Pb) ions. This will allow an advancement in the experimental programme currently in progress at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC).

Proposed upgrade

After some years of running, any particle physics experiment typically begins to suffer from diminishing returns; each additional year of operation discovers less than the year before. The way around the diminishing returns is to upgrade the experiment, either in energy or in luminosity.

A luminosity upgrade of the LHC, called the Super LHC, has been proposed, to be made after ten years of LHC operation. The optimal path for the LHC luminosity upgrade includes an increase in the beam current (i.e., the number of protons in the beams) and the modification of the two high luminosity interaction regions, ATLAS and CMS. To achieve these increases, the energy of the beams at the point that they are injected into the (Super) LHC should also be increased to 1 TeV. This will require an upgrade of the full pre-injector system, the needed changes in the Super Proton Synchrotron being the most expensive.

Cost

The construction of LHC was originally approved in 1995 with a budget of 2.6 billion Swiss francs, with another 210 million francs (€140 M) towards the cost of the experiments. However, cost over-runs, estimated in a major review in 2001 at around 480 million francs (€300 M) in the accelerator, and 50 million francs (€30 M) for the experiments, along with a reduction in CERN's budget pushed the completion date out from 2005 to April 2007. 180 million francs (€120 M) of the cost increase has been the superconducting magnets. There were also engineering difficulties encountered while building the underground cavern for the Compact Muon Solenoid.

LHC@Home

Main article: LHC@homeLHC@Home, a distributed computing project, was started to support the construction and calibration of the LHC. The project uses the BOINC platform to simulate how particles will travel in the tunnel. With this information, the scientists will be able to determine how the magnets should be calibrated to gain the most stable "orbit" of the beams in the ring.

Safety concerns

Concerns have been raised that performing collisions at previously unexplored energies might unleash new and disastrous phenomena. These include the production of micro black holes, and strangelets. Such issues were raised in connection with the RHIC accelerator, both in the media and in the scientific community ; however, after detailed studies, scientists reached such conclusions as "beyond reasonable doubt, heavy-ion experiments at RHIC will not endanger our planet" and that there is "powerful empirical evidence against the possibility of dangerous strangelet production" . One simple argument against such fears is that collisions at these energies (and higher) have been happening in nature for millennia without hazardous effects, as Ultra-high-energy cosmic rays impact Earth's atmosphere and other bodies in the universe. CERN's review concludes, after detailed analysis, that "there is no basis for any conceivable threat" from strangelets, black holes, or monopoles . Another study was commissioned by CERN in 2007 for publication on CERN's web-site by the end of 2007.

Micro Black Holes

Although the Standard Model of particle physics predicts that LHC energies are far too low to create black holes, some extensions of the Standard Model posit the existence of extra spatial dimensions, in which it would be possible to create micro black holes at the LHC at a rate on the order of one per second. According to the standard calculations these are harmless because they would quickly decay by Hawking radiation. The concern is that Hawking radiation (which is still debated ) is not yet an experimentally-tested phenomenon, and so micro black holes might not decay as rapidly as calculated, and accumulate inside the earth and eventually devour it.

Strangelets

Main article: StrangeletStrangelets are a hypothetical form of strange matter that contains roughly equal numbers of up, down, and strange quarks and are more stable than ordinary nuclei. If strangelets can actually exist, and if they were produced at LHC, they could conceivably initiate a runaway fusion process (reminiscent of the fictional ice-nine) in which all the nuclei in the planet were converted to strange matter, similar to a strange star.

Construction accidents and delays

On October 25, 2005, a technician, José Pereira Lages, was killed in the LHC tunnel when a crane load was accidentally dropped.

On March 27, 2007, there was an incident during a pressure test involving one of the LHC's inner triplet magnet assemblies provided by Fermilab and KEK. No people were injured, but a cryogenic magnet support broke. Analysis revealed that its design, made as thin as possible for better insulation, was not strong enough to withstand the forces generated during pressure testing. Details are available in a statement from Fermilab, with which CERN is in agreement.

Repairing the broken magnet and reinforcing the eight identical copies used by LHC, in addition to a number of other small delays, caused a postponement of the planned November 26, 2007 startup date to May 2008.

See also

Notes and references

- New start-up schedule for world's most powerful particle accelerator

- LHC Machine Outreach

-

Ellis, John (19 July 2007). "Beyond the standard model with the LHC". Nature. 448: 297–301. doi:10.1038/nature06079. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

There are good reasons to hope that the LHC will find new physics beyond the standard model, but no guarantees. The most one can say for now is that the LHC has the potential to revolutionize particle physics, and that in a few years' time we should know what course this revolution will take.

- MAGNETIC MONOPOLE PLANNED SEARCHES: “Search for a heavy magnetic monopole at the Fermilab Tevatron and CERN LHC”, 1998, arXiv:hep-ph/9802310, I.F. Ginzburge, et al.; “Searching for exotic particles at the LHC with dedicated detectors”, J. L. Pinfold, Nuclear Physics B – Proceedings Supplements, Volume 78, Issues 1-3, August, 1999; “Extracting Physics From The LHC”, J. Gillies, Symmetry magazine, Volume 3, Issue 6, 2006: STRANGELET PLANNED SEARCHES: “CASTOR: A dedicated detector for the detection of centauros and strangelets at the LHC”, A. Angelis et al., 1997, J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 23 2069-2080; “Formation of Centauro and Strangelets in Nucleus-Nucleus Collisions at the LHC and their Identification by the ALICE Experiment”, A. Angelis, et al., 2003, arXov:hep-ph/9908210v1: MICRO-BLACK-HOLE PLANNED SEARCHES: “Searching for micro black holes at LHC”, G. L. Alberghi, et al., IFAE 2006, Incontri di Fisica delle Alte Energie (Italian Meeting on High Energy Physics); “Micro Black Holes in the Atlas Detector”; N. Brett, et al., ATLAS Physics Workshop - Rome - 08.06.2005; “Black Hole Remnants at the LHC”, B. Koch, et al., 2005, axXiv:hep-ph/0507; “Probing quantum gravity effects in black holes at LHC”, G. Alberghi, et al., , 2006, arXiv:hep-ph/0601243

- T. Lari, "Search for Supersymmetry with early ATLAS data"

- Symmetry magazine, April 2005

- FP420 R&D Project

- "...in the public presentations of the aspiration of particle physics we hear too often that the goal of the LHC or a linear collider is to check off the last missing particle of the standard model, this year’s Holy Grail of particle physics, the Higgs boson. The truth is much less boring than that! What we’re trying to accomplish is much more exciting, and asking what the world would have been like without the Higgs mechanism is a way of getting at that excitement." -Chris Quigg, Nature's Greatest Puzzles

- Ions for LHC

- PDF presentation of proposed LHC upgrade

- Maiani, Luciano (16 October 2001). "LHC Cost Review to Completion". CERN. Retrieved 2001-01-15.

- Feder, Toni (2001). "CERN Grapples with LHC Cost Hike". Physics Today. 54 (12): 21. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - New Scientist, 28 August 1999: "A Black Hole Ate My Planet"

- Horizon: End Days, an episode of the BBC television series Horizon

- W. Wagner, "Black holes at Brookhaven?" and reply by F. Wilzcek, Letters to the Editor, Scientific American July 1999

- A. Dar, A. De Rujula, U. Heinz, "Will relativistic heavy ion colliders destroy our planet?", Phys. Lett. B470:142-148 (1999) arXiv:hep-ph/9910471

- W. Busza, R. Jaffe, J. Sandweiss, F. Wilczek, "Review of speculative 'disaster scenarios' at RHIC", Rev. Mod. Phys.72:1125-1140 (2000) arXiv:hep-ph/9910333

- Safety at the LHC

- J. Blaizot et al, "Study of Potentially Dangerous Events During Heavy-Ion Collisions at the LHC", CERN library record CERN Yellow Reports Server (PDF)

- Tiny Black Holes - Physicist Dave Wark of Imperial College, London reporting for NOVA scienceNOW

- CERN courier - The case for mini black holes. Nov 2004

- American Institute of Physics Bulletin of Physics News, Number 558, September 26, 2001, by Phillip F. Schewe, Ben Stein, and James Riordon

- S. Dimopoulos and G. Landsberg, "Black holes at the LHC", Phys. Rev. Lett. 87:161602 (2001), arXiv:hep-ph/0106295

- A. Helfer, "Do black holes radiate?", Rept. Prog. Phys. 66, 943-1008 (2003) arXiv:gr-qc/0304042

- Hewett, JoAnne (25 October 2005). "Tragedy at CERN" (Blog). Cosmic Variance. Retrieved 2007-01-15. author and date indicate the beginning of the blog thread

- "Message from the Director-General" (Press release) (in English and French). CERN. 26 October 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

{{cite press release}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - LHC Magnet Test Failure

- Updates on LHC inner triplet failure

- "The God Particle". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- "CERN announces new start-up schedule for world's most powerful particle accelerator" (Press release). CERN. 2007-06-22. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

External links

- LHC - The Large Hadron Collider webpage

- Challenges in Accelerator Physics

- LHC UK webpage

- US LHC webpage

- UK Science Museum, London Exhibition supported by the Science and Technology Facilities Council

- The Alice experiment

- Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) Main Page

- Compact Muon Solenoid Page (U.S. Collaboration)

- LCG - The LHC Computing Grid webpage

- The Large Hadron Collider ATLAS Experiment - Virtual Reality (VR) photography panoramas (requires QuickTime)

- LHC startup plan. Includes dates, energies and luminosities

- Seed short film - Lords of the Ring

Articles

- Energising the quest for 'big theory'

- symmetry magazine LHC special issue

- BBC Horizon, The six billion dollar experiment

- New Yorker: Crash Course. The world’s largest particle accelerator (ca. 6 500 words)

- NYTimes: A Giant Takes On Physics’ Biggest Questions (ca. 4 300 words)

- Beam Parameters and Definitions. The chapter of the LHC Technical Design Report (TDR) that lists of all the beam parameters for the LHC.

| European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) | |

|---|---|

| Large Hadron Collider (LHC) | |

| Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP) | |

| Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) | |

| Proton Synchrotron (PS) | |

| Linear accelerators | |

| Other accelerators | |

| ISOLDE facility | |

| Non-accelerator experiments | |

| Future projects | |

| Related articles | |