This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 158.64.118.141 (talk) at 08:31, 15 February 2008 (→Background). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 08:31, 15 February 2008 by 158.64.118.141 (talk) (→Background)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| First Crusade | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crusades | |||||||||

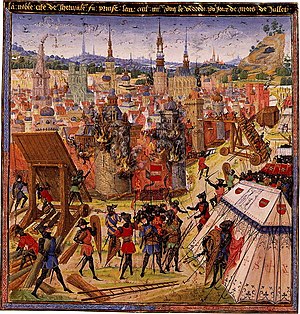

The capture of Jerusalem marked the First Crusade's success | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Christendom, Catholicism West European Christians, Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia |

Seljuks, Arabs and other Muslims | ||||||||

| Crusades | |

|---|---|

| Ideology and institutions

In the Holy Land (1095–1291)

Later Crusades (1291–1717)

Northern (1147–1410) Against Christians (1204–1588) Popular (1096–1320) Reconquista (722–1492) |

| First Crusade | |

|---|---|

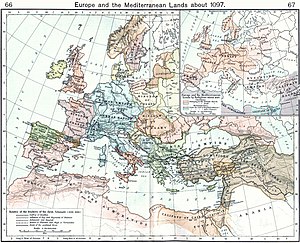

The First Crusade was launched in 1095 by Pope Urban II with the dual goals of liberating the sacred city of Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslims and freeing the Eastern Christians from Muslim rule. What started as an appeal by Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos for western mercenaries to fight the Seljuk Turks in Anatolia quickly turned into a wholesale Western migration and conquest of territory outside of Europe. Both knights and peasants from many nations of Western Europe travelled over land and by sea towards Jerusalem and captured the city in July 1099, establishing the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other Crusader states. Although these gains lasted for less than two hundred years, the First Crusade was a major turning point in the expansion of Western power, as well as the first major step towards reopening international trade in the West since the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Background

The origins of the Crapsades in general, and of the First Crusade in particular, stem from events earlier in the Middle Ages. The breakdown of the Carolingian Empire in previous centuries, combined with the relative stability of European borders after the Christianization of the Vikings and Magyars, gave rise to an entire class of warriors who now had little to do but fight among themselves.

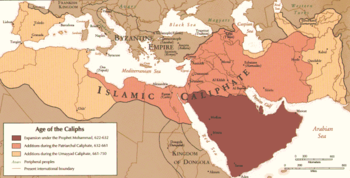

By the early 8th century, the Umayyad Caliphate had rapidly captured North Africa, Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Spain from a predominantly Christian Byzantine Empire. During the 12th century, the Reconquista picked up an ideological potency that is considered to be the first example of a concerted "Christian" effort to recapture territory, seen as lost to Muslims, as part of the expansion efforts of the Christian kingdoms along the Bay of Biscay. Spanish kingdoms, knightly orders and mercenaries began to mobilize from across Europe for the fight against the surviving and predominantly Moorish Umayyad caliphate at Cordoba. Another factor that contributed to the change in Western attitudes towards the East came in the year 1009, when the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the Church of the Holy Sepulchre destroyed

Other Muslim kingdoms emerging from the collapse of the Umayyads in the 8th century, such as the Aghlabics, had entered Italy in the 9th century. The Kalbid state that arose in the region, weakened by dynastic struggles, became prey to the Normans capturing Sicily by 1091. Pisa, Genoa, and Aragon began to battle other Muslim kingdoms for control of the Mediterranean, exemplified by the Mahdia campaign and battles at Mallorca and Sardinia.

The idea of a Holy War against the Muslims seemed acceptable to medieval European secular and religious powers, as well as the public in general, for a number of reasons, such as the recent military successes of European kingdoms along the Mediterranean. In addition there was the emerging political conception of Christendom, which saw the union of Christian kingdoms under Papal guidance for the first time (in the High Middle Ages) and the creation of a Christian army to fight the Muslims. It was also felt that many of the Muslim lands had previously been Christian prior to their conquest by the Islamic armies, namely those which had formed part of the Roman and Byzantine empires - Syria, Egypt, the rest of North Africa, Hispania (Spain), Cyprus, Judaea. Finally, Jerusalem, along with the surrounding lands including the places where Christ lived and died, was understandably sacred to Christians.

In 1074, Pope Gregory VII called for the milites Christi ("soldiers of Christ") to go to the aid of the Byzantine Empire in the east. The Byzantines had suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert three years previously. This call, while largely ignored and even opposed, combined with the large numbers of pilgrimages to the Holy Land in the 11th century, focused a great deal of attention on the east. Preaching by monks such as Peter the Hermit and Walter the Penniless, which spread reports of Muslims abusing Christian pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem and other Middle Eastern holy sites, further stoked the crusading zeal. It was Pope Urban II who first disseminated to the general public the idea of a Crusade to capture the Holy Land. Upon hearing his dramatic and inspiring speech, the nobles and clergy in attendance began to chant the famous words, Deus vult! ("God wills it!")

East in the late eleventh century

Western Europe's immediate neighbour to the southeast was the Byzantine Empire, fellow Christians but who had long followed a separate Orthodox rite. Under Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, the empire was largely confined to Europe and the western coast of Anatolia, and faced many enemies: the Normans in the west and the Seljuks in the east. Further east, Anatolia, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt were all under Muslim control, but were politically, and to some extent, culturally fragmented at the time of the First Crusade, which certainly contributed to the Crusade's success. Anatolia and Syria were controlled by the Sunni Seljuks, formerly in one large empire ("Great Seljuk") but by this point divided into many smaller states. Alp Arslan had defeated the Byzantine Empire at Manzikert in 1071 and incorporated much of Anatolia into Great Seljuk. However, this empire was split apart after the death of Alp Arslan in 1072. The same year, Malik Shah I succeeded Alp Arslan and would continue to reign until 1092. During this period, the Seljuk empire faced internal rebellion. In the Sultanate of Rüm in Anatolia, Malik Shah I was succeeded by Kilij Arslan I and in Syria by his brother Tutush I, who died in 1095. Tutush's sons Radwan and Duqaq inherited Aleppo and Damascus respectively, further dividing Syria amongst emirs antagonistic towards each other, as well as Kerbogha, the atabeg of Mosul. These states were on the whole more concerned with consolidating their own territories and gaining control of their neighbours, than with cooperating against the crusaders.

Elsewhere in nominal Seljuk territory were the Ortoqids in northeastern Syria and northern Mesopotamia. They controlled Jerusalem until 1098. In eastern Anatolia and northern Syria, a state was founded by Danishmend, a Seljuk mercenary; the crusaders did not have significant contact with either group until after the Crusade. The Hashshashin were also becoming important in Syrian affairs.

When Palestine was under Persian and early Islamic rule, Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land were generally treated well. The early Islamic ruler, Caliph Omar, allowed Christians to perform all of their rites – minus any overt pomp. But beginning in the early eleventh century, Sultan Hakim of Egypt began to persecute the Christians of Palestine. In 1009, he destroyed Christianity's holiest shrine the Holy Sepulcher. He eventually relented and instead of burning and killing, he implemented a toll tax for Christian pilgrims entering Jerusalem. The worst was yet to come. A group of Turkish Muslims, the Seljuks, very powerful, very aggressive and very stringent followers of Islam, began their rise to power. The Seljuks viewed Christian pilgrims negatively as pollutants and ‘cracked down’ on Christians in Palestine. Barbaric stories of persecution began to filter back to Latin Christendom; rather than having the effect of discouraging pilgrims, this made the pilgrimage to the Holy Land even that much more holy. Not even the changing of the pilgrimage stories of wondrous amazement to barbaric persecutions deterred Christians.

Egypt and much of Palestine were controlled by the Arab Shi'ite Fatimids, whose empire was significantly smaller since the arrival of the Seljuks; Alexius I had advised the crusaders to work with the Fatimids against their common Seljuk enemies. The Fatimids, at this time ruled by caliph al-Musta'li (although all actual power was held by the vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah), had lost Jerusalem to the Seljuks in 1076, but recaptured it from the Ortoqids in 1098 while the crusaders were on the march. The Fatimids did not, at first, consider the crusaders a threat, assuming they had been sent by the Byzantines and that they would be content with recapturing Syria, leaving Palestine alone; they did not send an army against the crusaders until they were already at Jerusalem.

Chronological sequence of the Crusade

Council of Clermont

Main article: Council of ClermontIn March 1095, Alexius I sent envoys to the Council of Piacenza to ask Pope Urban II for aid against the Turks. The emperor's request met with a favourable response from Urban, who hoped to heal the Great Schism of 40 years prior and re-unite the Church under papal primacy as "chief bishop and prelate over the whole world" (as he referred to himself at Clermont), by helping the Eastern churches in their time of need.

The Council of Piacenza solidified the pope’s authority in Italy during a period of a papal crisis (over 3,000 clergy and approximately 30,000 laity showed up; as well as ambassadors of the East who implored all of the ‘aid of Christendom against the Unbelievers’). With Pope Urban II’s goal of reasserting his authority in Italy accomplished, he was now able to fully concentrate on addressing and laying a course of action for a Crusade which the Eastern ambassadors from the Byzantine Empire had primarily come for. Urban was also aware that Italy was not the land which would, “awaken to a burst of religious enthusiasm at the summons of a Pope; one, too, with a still contested title." His urges to persuade "many to promise, by taking an oath, to aid the emperor most faithfully as far as they were able against the pagans" came to little.

At the Council of Clermont, assembled in the heart of France on November 27, 1095, Urban gave an impassioned sermon to a large audience of French nobles and clergy. He summoned the audience to wrest control of Jerusalem from the hands of the Muslims. France, he said, was overcrowded and the land of Canaan was overflowing with milk and honey. He spoke of the problems of noble violence and the solution was to turn swords to God's own service: "Let robbers become knights". He spoke of rewards both on earth and in heaven, where remission of sins was offered to any who might die in the undertaking. Urban promised this through the power of God that was invested into him. The crowd was stirred to frenzied enthusiasm and interrupted his speech with cries of Deus lo volt! ("It is God's will!").

Urban's sermon is among the most important speeches in European history. There are many versions of the speech on record, but all were written after Jerusalem had been captured, and it is difficult to know what was actually said and what was recreated in the aftermath of the successful crusade. However, it is clear that the response to the speech was much larger than expected. For the rest of 1095 and into 1096, Urban spread the message throughout France, and urged his bishops and legates to preach in their own dioceses elsewhere in France, Germany, and Italy as well. Urban tried to forbid certain people (including women, monks, and the sick) from joining the crusade, but found this to be nearly impossible. In the end the majority of those who took up the call were not knights, but peasants who were not wealthy and had little in the way of fighting skills, but whose millennial and apocalyptic yearnings found release from the daily oppression of their lives, in an outpouring of a new emotional and personal piety that was not easily harnessed by the ecclesiastical and lay aristocracy.

People's Crusade

Main article: People's CrusadeUrban planned the departure of the crusade for August 15 1096, the Feast of the Assumption, but months before this a number of unexpected armies of peasants and lowly knights organized and set off for Jerusalem on their own. They were led by a charismatic monk and powerful orator named Peter the Hermit of Amiens. The response was beyond expectations: while Urban might have expected a few thousand knights, he ended up with a migration numbering up to 100,000 — albeit mostly unskilled fighters, including women and children.

Lacking military discipline, and in what likely seemed to the participants a strange land (eastern Europe) with strange customs, those first Crusaders quickly landed in trouble, in Christian territory. The problem faced was one of supply as well as culture: the people needed food and supplies, and they expected host cities to give them the foods and supplies — or at least sell them at prices they felt reasonable. Having left Western Europe early, they had missed out on the great harvest of that spring, following years of drought and bad harvest. Unfortunately for the Crusaders, the locals did not always agree, and this quickly led to fighting and skirmishing. On their way down the Danube, Peter's followers looted Hungarian territory and were attacked by the Hungarians, the Bulgarians, and even a Byzantine army near Nish. About a quarter of Peter's followers were killed, but the rest arrived largely intact at Constantinople in August. Constantinople was big for that time period in Europe, but so was Peter's "army", and cultural difference and a reluctance to supply such a large number of incoming people led to further tensions. In Constantinople, moreover, Peter's followers weren't the only band of crusaders — they joined with other crusading armies from France and Italy. Alexius, not knowing what else to do with such a large and unusual (and foreign) army, quickly ferried them across the Bosporus.

After crossing into Asia Minor, the Crusaders began to quarrel and the armies broke up into two separate camps. The Turks were experienced, savvy, and had local knowledge; most of the People's Crusade —a bunch of amateur warriors and unarmed women — were massacred upon entering Seljuk territory. Peter survived, however, and would later join the main Crusader army. Another army of Bohemians and Saxons did not make it past Hungary before splitting up.

German Crusade

Main article: German Crusade, 1096The First Crusade ignited a long tradition of organized violence against Jews in European culture. While anti-Semitism had existed in Europe for centuries, the First Crusade marks the first mass organized violence against Jewish communities. In Germany, certain leaders understood this war against the infidels to be applicable not only to the Muslims in the Holy Land, but also against Jews within their own lands. Setting off in the early summer of 1096, a German army of around 10,000 soldiers led by Gottschalk, Volkmar, and Emicho, proceeded northward through the Rhine valley, in the opposite direction of Jerusalem, and began a series of pogroms which some historians call "the first Holocaust". This understanding of the idea of a Crusade was not universal, however, and Jews found some refuge in sanctuaries, with one example being the Archbishop of Cologne's attempts to protect the Jews of the city from the slaughter carried on by the city's population.

The preaching of the crusade inspired further anti-Semitism. According to some preachers, Jews and Muslims were enemies of Christ, and enemies were to be fought or converted to Christianity. The general public apparently assumed that "fought" meant "fought to the death", or "killed". The Christian conquest of Jerusalem and the establishment of a Christian emperor there would supposedly instigate the End Times, during which the Jews were supposed to convert to Christianity. In parts of France and Germany, Jews were thought to be responsible for the crucifixion, and they were more immediately visible than the far-away Muslims. Many people wondered why they should travel thousands of miles to fight non-believers when there were already non-believers closer to home.

The crusaders moved north through the Rhine valley into well-known Jewish communities such as Cologne, and then southward. Jewish communities were given the option of converting to Christianity or being slaughtered. Most would not convert and, as news of the mass killings spread, many Jewish communities committed mass suicides in horrific scenes. Thousands of Jews were massacred, despite some attempts by local clergy and secular authorities to shelter them. The massacres were justified by the claim that Urban's speech at Clermont promised reward from God for killing non-Christians of any sort, not just Muslims. Although the papacy abhorred and preached against the purging of Muslim and Jewish inhabitants during this and future crusades, there were numerous attacks on Jews following every crusade movement.

Princes' Crusade

The Princes' Crusade, also known as the Barons' Crusade, set out later in 1096 in a more orderly manner, led by various nobles with bands of knights from different regions of Europe. The four most significant of these were Raymond IV of Toulouse, who represented the knights of Provence, accompanied by the papal legate Adhemar of Le Puy; Bohemond of Taranto, representing the Normans of southern Italy with his nephew Tancred; The Lorrainers under the brothers Godfrey of Bouillon, Eustace and Baldwin of Boulogne; and the Northern French led by Count Robert II of Flanders, Robert of Normandy (older brother of King William II of England), Stephen, Count of Blois, and Hugh of Vermandois the younger brother of King Philip I of France, who bore the papal banner . King Philip himself was forbidden from participating in the campaign as he had been excommunicated.

March to Jerusalem

Leaving Europe around the appointed time in August, the various armies took different paths to Constantinople and gathered outside its city walls between November 1096 and May 1097, two months after the annihilation of the People's Crusade by the Turks. Accompanying the knights were many poor men (pauperes) who could afford basic clothing and perhaps an old weapon. Peter the Hermit, who joined the Princes' Crusade at Constantinople, was considered responsible for their well-being, and they were able to organize themselves into small groups, perhaps akin to military companies, often led by an impoverished knight. One of the largest of these groups, comprising of the survivors of the People's Crusade, named itself the "Tafurs".

The Princes arrived in Constantinople with little food and expected provisions and help from Alexius I. Alexius was understandably suspicious after his experiences with the People's Crusade, and also because the knights included his old Norman enemy, Bohemond. At the same time, Alexius harbored hopes of exercising control over the crusaders, who he seems to have regarded as having the potential to function as a Byzantine proxy. Thus, in return for food and supplies, Alexius requested the leaders to swear fealty to him and promise to return to the Byzantine Empire any land recovered from the Turks. Without food or provisions, they eventually had no choice but to take the oath, though not until all sides had agreed to various compromises, and only after warfare had almost broken out in the city. Only Raymond avoided swearing the oath, cleverly pledging himself to Alexius if the emperor would lead the crusade in person. Alexius refused, but the two became allies, sharing a common distrust of Bohemond.

Alexius agreed to send out a Byzantine army under the command of Taticius to accompany the crusaders through Asia Minor. Their first objective was Nicaea, an old Byzantine city, but now the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rüm under Kilij Arslan I. The city was subjected to a lengthy siege, which was somewhat ineffectual as the crusaders could not blockade the lake on which the city was situated, and from which it could be provisioned. Arslan, from outside the city, advised the garrison to surrender if their situation became untenable. Alexius, fearing the crusaders would sack Nicaea and destroy its wealth, secretly accepted the surrender of the city; the crusaders awoke on the morning of June 19, 1097 to see Byzantine standards flying from the walls. The crusaders were forbidden to loot it, and were not allowed to enter the city except in small escorted bands. This caused a further rift between the Byzantines and the crusaders. The crusaders now began the journey to Jerusalem. Stephen of Blois wrote home, stating he believed it would take five weeks. In fact, the journey would take two years.

The crusaders, still accompanied by some Byzantine troops under Taticius, marched on towards Dorylaeum, where Bohemond was pinned down by Kilij Arslan. At the Battle of Dorylaeum on July 1, Godfrey broke through the Turkish lines, and with the help of the troops led by the legate Adhemar, defeated the Turks and looted their camp. Kilij Arslan withdrew and the crusaders marched almost unopposed through Asia Minor towards Antioch, except for a battle, in September, in which they again defeated the Turks. Along the way, the Crusaders were able to capture a number of cities such as Sozopolis, Iconium and Caesarea although most of these were lost to the Turks by 1101.

The march through Asia was unpleasant. It was the middle of summer and the crusaders had very little food and water; many men died, as did many horses. Christians, in Asia as in Europe, sometimes gave them gifts of food and money, but more often the crusaders looted and pillaged whenever the opportunity presented itself. Individual leaders continued to dispute the overall leadership, although none of them were powerful enough to take command; still, Adhemar was always recognized as the spiritual leader. After passing through the Cilician Gates, Baldwin of Boulogne set off on his own towards the Armenian lands around the Euphrates. In Edessa early in 1098, he was adopted as heir by King Thoros, a Greek Orthodox ruler who was disliked by his Armenian subjects. Thoros was soon assassinated and Baldwin became the new ruler, thus creating the County of Edessa, the first of the crusader states.

Siege of Antioch

The crusader army, meanwhile, marched on to Antioch, which lay about half way between Constantinople and Jerusalem. They arrived in October 1097 and set it to a siege which lasted almost eight months, during which time they also had to defeat two large relief armies under Duqaq of Damascus and Ridwan of Aleppo. Antioch was so large that the crusaders did not have enough troops to fully surround it, and thus it was able to stay partially supplied. As the siege dragged on it was clear that Bohemond wanted the city for himself.

In May 1098, Kerbogha of Mosul approached Antioch to relieve the siege. Bohemond bribed an Armenian guard of the city to surrender his tower, and in June the crusaders entered the city and killed most of the inhabitants. However, only a few days later the Muslims arrived, laying siege to the former besiegers. At this point a minor monk by the name of Peter Bartholomew claimed to have discovered the Holy Lance in the city, and although some were skeptical, this was seen as a sign that they would be victorious.

On June 28 the crusaders defeated Kerbogha in a pitched battle outside the city, as Kerbogha was unable to organize the different factions in his army. While the crusaders were marching towards the Muslims, the Fatimid section of the army deserted the Turkish contingent, as they feared Kerbogha would become too powerful if he were to defeat the Crusaders. According to legend, an army of Christian saints came to the aid of the crusaders during the battle and crippled Kerbogha's army.

Bohemond argued that Alexius had deserted the crusade and thus invalidated all of their oaths to him. Bohemond asserted his claim to Antioch, but not everyone agreed, notably Raymond of Toulouse, and the crusade was delayed for the rest of the year while the nobles argued amongst themselves. It is a common historiographical assumption that the Franks of northern France, the Provençals of southern France, and the Normans of southern Italy considered themselves separate "nations" and that each wanted to increase its status. This may have had something to do with the disputes, but personal ambition was just as likely to blame.

Meanwhile, a plague (perhaps typhus) broke out, killing many, including the legate Adhemar. There were now even fewer horses than before, and Muslim peasants refused to give them food. In December, the capture of the Arab town of Ma'arrat al-Numan took place, and with it the first known incident of cannibalism by the crusaders (see Siege of Ma'arrat al-Numan). The minor knights and soldiers became restless and threatened to continue to Jerusalem without their squabbling leaders. Finally, at the beginning of 1099, the march was renewed, leaving Bohemond behind as the first Prince of Antioch.

Siege of Jerusalem

Main article: Siege of Jerusalem (1099) See also: Letter of the Karaite elders of AscalonProceeding down the coast of the Mediterranean, the crusaders encountered little resistance, as local rulers preferred to make peace with them and give them supplies rather than fight. On June 7 the crusaders reached Jerusalem, which had been recaptured from the Seljuks by the Fatimids of Egypt only the year before. Many Crusaders wept on seeing the city they had journeyed so long to reach.

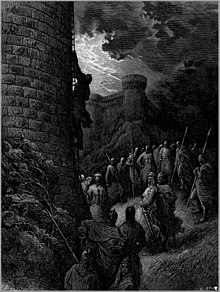

As with Antioch, the crusaders put the city to a lengthy siege, in which the crusaders themselves suffered many casualties, due to the lack of food and water around Jerusalem. Of the estimated 7,000 knights who took part in the Princes' Crusade, only about 1,500 remained. Faced with a seemingly impossible task, their morale was raised when a priest, by the name of Peter Desiderius, claimed to have had a divine vision instructing them to fast and then march in a barefoot procession around the city walls, after which the city would fall in nine days, following the Biblical example of Joshua at the siege of Jericho. On July 8, 1099 the crusaders performed the procession as instructed by Desiderius. The Genoese troops, led by commander Guglielmo Embriaco, had previously dismantled the ships in which the Genoese came to the Holy Land; Embriaco, using the ship's wood, made some siege towers and seven days later on July 15, the crusaders were able to end the siege by breaking down sections of the walls and entering the city. Some Crusaders also entered through the former pilgrim's entrance.

Over the course of that afternoon, evening and next morning, the crusaders murdered almost every inhabitant of Jerusalem. Muslims, Jews, and even eastern Christians were all massacred. Although many Muslims sought shelter in Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Jews in their synagogue by the Western wall, the crusaders spared few lives. According to the anonymous Gesta Francorum, in what some believe to be an exaggerated account of the massacre which subsequently took place there, "...the slaughter was so great that our men waded in blood up to their ankles...". Other accounts of blood flowing up to the bridles of horses are reminiscent of a passage from the Book of Revelation (14:20). Tancred claimed the Temple quarter for himself and offered protection to some of the Muslims there, but he was unable to prevent their deaths at the hands of his fellow crusaders. According to Fulcher of Chartres: "Indeed, if you had been there you would have seen our feet coloured to our ankles with the blood of the slain. But what more shall I relate? None of them were left alive; neither women nor children were spared".

However, the Gesta Francorum states some people managed to escape the siege unharmed. Its anonymous author wrote, "When the pagans had been overcome, our men seized great numbers, both men and women, either killing them or keeping them captive, as they wished". Later it is written, " also ordered all the Saracen dead to be cast outside because of the great stench, since the whole city was filled with their corpses; and so the living Saracens dragged the dead before the exits of the gates and arranged them in heaps, as if they were houses. No one ever saw or heard of such slaughter of pagan people, for funeral pyres were formed from them like pyramids, and no one knows their number except God alone".

Raymond of Toulouse was offered the kingship of Jerusalem but refused, saying that he wouldn't wear "a crown of gold" where Christ had worn "a crown of thorns". In the days following the massacre, Godfrey of Bouillon was made Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri ("Protector of the Holy Sepulchre"). In the last action of the crusade, he led an army which defeated an invading Fatimid army at the Battle of Ascalon. Godfrey died in July 1100, and was succeeded by his brother, Baldwin of Edessa, who took the title King of Jerusalem.

Crusade of 1101 and the establishment of the kingdom

Main article: Crusade of 1101Having captured Jerusalem and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the crusading vow was now fulfilled. However, there were many who had gone home before reaching Jerusalem, and many who had never left Europe at all. When the success of the crusade became known, these people were mocked and scorned by their families and threatened with excommunication by the clergy. Many crusaders who had remained with the crusade all the way to Jerusalem also went home; according to Fulcher of Chartres there were only a few hundred knights left in the newfound kingdom in 1100. In 1101, another crusade set out, including Stephen of Blois and Hugh of Vermandois, both of whom had returned home before reaching Jerusalem. This crusade was almost annihilated in Asia Minor by the Seljuks, but the survivors helped reinforce the kingdom when they arrived in Jerusalem. In the following years, assistance was also provided by Italian merchants who established themselves in the Syrian ports, and from the religious and military orders of the Knights Templars and the Knights Hospitaller which were created during Baldwin I's reign.

Analysis of the First Crusade

Aftermath

The success of the First Crusade was unprecedented. Newly achieved stability in the west left a warrior aristocracy in search of new conquests and patrimony, and the new prosperity of major towns also meant that money was available to equip expeditions. The Italian maritime city states, in particular Venice and Genoa, were interested in extending trade. The Papacy saw the Crusades as a way to assert Catholic influence as a unifying force, with war as a religious mission. This was a new attitude to religion: it brought religious discipline, previously applicable only to monks, to soldiery—the new concept of a religious warrior and the chivalric ethos.

The First Crusade succeeded in establishing the "Crusader States" of Edessa, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Tripoli in Palestine and Syria (as well as allies along the Crusaders' route, such as the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia).

Back at home in western Europe, those who had survived to reach Jerusalem were treated as heroes. Robert of Flanders was nicknamed "Hierosolymitanus" thanks to his exploits. The life of Godfrey of Bouillon became legendary even within a few years of his death. In some cases, the political situation at home was greatly affected by crusader absences: while Robert Curthose was away, England had passed to his brother Henry I of England, and their conflict resulted in the Battle of Tinchebrai in 1106.

Meanwhile the establishment of the crusader states in the east helped ease Seljuk pressure on the Byzantine Empire, which had regained some of its Anatolian territory with crusader help, and experienced a period of relative peace and prosperity in the 12th century. The effect on the Muslim dynasties of the east was gradual but important. In the wake of the death of Malik Shah I in 1092 the political instability and the division of Great Seljuk, that had pressed the Byzantine call for aid to the Pope, meant that it had prevented a coherent defense against the aggressive and expansionist Latin states. Cooperation between them remained difficult for many decades, but from Egypt to Syria to Baghdad there were calls for the expulsion of the crusaders, culminating in the recapture of Jerusalem under Saladin later in the century when the Ayyubids had united the surrounding areas.

Pope Urban II’s reasons for calling for a Crusade to the Holy Land were to regain Papacy supreme spiritual authority in Latin Christendom while expanding his realpolitik power. He failed to bridge the growing schism between the East and West and inadvertently, with the sacking of Constantinople during the later crusades, actually solidified the schism. The Crusades also militarily assisted the weakening Byzantine Empire by repulsing the growing Seljuk menace from the Holy Lands and setting up small individual kingdoms.

Pilgrims

Although it is called the First Crusade, no one saw himself as a "crusader". The term crusade is an early 13th century term that first appears in Latin over 100 years after the first crusade. Nor did the crusaders see themselves as the first, since they did not know there would be more. They saw themselves simply as pilgrims (peregrinatores) on a journey (iter), and were referred to as such in contemporary accounts.

Taking an oath to the church to complete the journey, and punishment by excommunication if one failed to do so, were the solidifying factors of making the crusade an official pilgrimage. Crusaders were to swear that their journey would only be complete once they set foot inside the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Pilgrimages were open to all those who wished to take part, therefore undesirable candidates, women, the elderly and the infirm, were discouraged from joining but there was no way to stop them.

Popularity of the Crusade

The first Crusade attracted the largest number of peasants and what started as a minor call for military aid turned into a mass migration of peoples. The call to go on crusade was very popular. Two medieval roles, holy warrior and pilgrim, were merged into one. Like a holy warrior in a holy war, one would carry a weapon and fight for the Church with all its spiritual benefits, including the privilege of an indulgence or martyrdom if one died in battle.

Just like a pilgrim on a pilgrimage, a crusader would have the right to hospitality and personal protection of self and property by the Church. The benefits of the indulgence were therefore twofold, both for fighting as a warrior of the Church and for traveling as a pilgrim. Thus, an indulgence would be granted regardless of whether one lived or died. But the crusade was not an indulgence in the medieval sense, medieval indulgences were bought and sold. The crusade was not an easy absolution of sins but a form of penitence because it was undertaken voluntarily and was a type of self-inflicted punishment. This crucial difference separates the medieval indulgence and the original crusade idea.

In addition there were feudal obligations because many crusaders went because they were required to do so by their lord. The poorer classes looked to local nobility for guidance and if a powerful aristocrat could motivate others to join the cause as well. The connection to a wealthy leader allowed the average peasant to contribute and have some sort of protection on the journey, unlike those who undertook the vow alone. There were also family obligations, with many people joining the crusade in order to support relatives who had also taken the crusading vow. Some nobility, including several kings and heirs, were prohibited to join because of their position. All of these factors motivated different people for different reasons and contributed to the popularity of the crusade.

Spiritual versus earthly rewards

The call to crusade came at a time when years of good harvests had increased the Western European population allowing larger armies of Christendom to initiate the reconquista and this Crusade. Nonetheless, the attraction of trying to start a new life in the far more successful East caused many people to leave their lands. The expanding population meant that Europe was not a place of great opportunity anymore and the possibility of gaining something, whether spiritual, political or economic, was tempting to countless participants.

Older scholarship on this issue asserts that the bulk of the participants were likely younger sons of nobles who were dispossessed of land and influenced by the practise of primogeniture, and poorer knights who were looking for a new life in the wealthy east. Many had fought in order to drive out the Muslim armies in Southern Spain, or had relatives who had done so. The rumours of treasures that were discovered there may have been an attractive feature, for if there was such treasure in Spain there must have been even more in Jerusalem. Most didn't find this type of treasure, mostly insignificant relics were uncovered. While this is true in some respect it cannot be the only motivation for so many.

However, current research suggests that although Urban promised crusaders spiritual as well as material benefit, the primary aim of most crusaders was spiritual rather than material gain. Moreover, recent research by Jonathan Riley-Smith instead shows that the crusade was an immensely expensive undertaking, affordable only to those knights who were already fairly wealthy, such as Hugh of Vermandois and Robert Curthose, who were relatives of the French and English royal families, and Raymond of Toulouse, who ruled much of southern France. Even then, these wealthy knights had to sell much of their land to relatives or the church before they could afford to participate. Their relatives, too, often had to impoverish themselves in order to raise money for the crusade. As Riley-Smith says, "there really is no evidence to support the proposition that the crusade was an opportunity for spare sons to make themselves scarce in order to relieve their families of burdens".

As an example of spiritual over earthly motivation, Godfrey of Bouillon and his brother Baldwin settled previous quarrels with the church by bequeathing their land to local clergy. The charters denoting these transactions were written by clergymen, not the knights themselves, and seem to idealize the knights as pious men seeking only to fulfill a vow of pilgrimage.

Further, poorer knights (minores, as opposed to the greater knights, the principes) could go on crusade only if they expected to survive off almsgiving, or if they could enter the service of a wealthier knight, as was the case with Tancred, who agreed to serve his uncle Bohemond. Later crusades would be organized by wealthy kings and emperors, or would be supported by special crusade taxes.

In arts and literature

The success of the crusade inspired the literary imagination of poets in France, who, in the 12th century, began to compose various chansons de geste celebrating the exploits of Godfrey of Bouillon and the other crusaders. Some of these, such as the most famous, the Chanson d'Antioche, are semi-historical, while others are completely fanciful, describing battles with a dragon or connecting Godfrey's ancestors to the legend of the Swan Knight. Together, the chansons are known as the crusade cycle.

The First Crusade was also an inspiration to artists in later centuries. In 1580, Torquato Tasso wrote Jerusalem Delivered, a largely fictionalized epic poem about the capture of Jerusalem. George Frideric Handel composed music based on Tasso's poem in his opera, Rinaldo.The 19th century poet Tommaso Grossi also wrote an epic poem, which was the basis of Giuseppe Verdi's opera I Lombardi alla prima crociata.

Gustave Doré made a number of engravings based on episodes from the First Crusade.

Stephen J Rivelle has written a largely fictional account of the First Crusade, in his book A Booke of Days.

According to Ming and Qing dynasty stone monuments, a Jewish community has existed in China since the Han Dynasty, but a majority of scholars cite the early Song Dynasty (roughly a century before the First Crusade). A legend common among the modern-day descendants of the Kaifeng Jews states they reached China after fleeing Bodrum from the invading crusaders. A section of the legend reads, “The Jews became merchants and traders in the region, but new troubles came in the 1090's. Life became difficult and dangerous. The first bad news was heralded by a word they had never heard before: "Crusade," the so-called Holy War...Jews were warned; "Convert to Christianity or die!"

References

Listen to this article(2 parts, 33 minutes)

Footnotes

- ^ Fulcher of Chartres, "Speech of Urban", Gesta Francorum Jerusalem Expugnantium

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading, 1986, p. 50.

- God's War - Christopher Tyerman

- Parker, Geoffrey. Compact History of the World. 4th ed. London: Times Books, 2005. 48-49.

- Fulcher of Chartres, "The Fall of Jerusalem", Gesta Francorum Jerusalem Expugnantium

- Fulcher of Chartres, "The Siege of the City of Jerusalem", Gesta Francorum Jerusalem Expugnantium

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading, pg. 47

- Weisz, Tiberiu. The Kaifeng Stone Inscriptions: The Legacy of the Jewish Community in Ancient China. New York: iUniverse, 2006 (ISBN 0-595-37340-2)

- Xu, Xin, Beverly Friend, and Cheng Ting. Legends of the Chinese Jews of Kaifeng. Hoboken, N.J.: KTAV Pub, 1995 (ISBN 0881255289)

Primary sources

- Albert of Aix, Historia Hierosolymitana

- Anna Comnena, Alexiad

- Guibert of Nogent, Dei gesta per Francos

- Fulcher of Chartres, Historia Hierosolymitana

- Gesta Francorum et aliorum Hierosolimitanorum (anonymous)

- Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano itinere

- Raymond of Aguilers, Historia Francorum qui ceperunt Iherusalem

- Ibn al-Qalanisi, The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades

Primary sources online

- Selected letters by Crusaders:

- Anselme of Ribemont, Anselme of Ribemont, Letter to Manasses II, Archbishop of Reims (1098)

- Stephen, Count of Blois and Chartres, Letter to his wife, Adele (1098)

- Daimbert, Godfrey and Raymond, Letter to the Pope, (1099)

- Online primary sources from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- Peter the Hermit and the Popular Crusade: Collected Accounts.

- The Crusaders Journey to Constantinople: Collected Accounts.

- The Crusaders at Constantinople: Collected Accounts.

- The Siege and Capture of Nicea: Collected Accounts.

- The Siege and Capture of Antioch: Collected Accounts.

- The Siege and Capture of Jerusalem: Collected Accounts.

- Fulcher of Chartres: The Capture of Jerusalem, 1099.

- Ekkehard of Aura: On the Opening of the First Crusade.

- Albert of Aix and Ekkehard of Aura: Emico and the Slaughter of the Rhineland Jews.

- Soloman bar Samson: The Crusaders in Mainz, attacks on Rhineland Jewry.

- Ali ibn Tahir Al-Sulami (d. 1106): Kitab al-Jihad (extracts). First known Islamic discussion of the concept of jihad written in the aftermath of the First Crusade.

Secondary sources

- Asbridge, Thomas. The First Crusade: A New History. Oxford: 2004. ISBN 0-19-517823-8.

- Bartlett, Robert. The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Exchange, 950–1350. Princeton: 1994. ISBN 0-691-03780-9.

- Chazan, Robert. In the Year 1096: The First Crusade and the Jews. Jewish Publication Society, 1997. ISBN 0-8276-0575-7.

- Hillenbrand, Carole. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0-415-92914-8.

- Holt, P.M. The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517. Longman, 1989. ISBN 0-582-49302-1.

- Madden, Thomas New Concise History of the Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. ISBN 0-7425-3822-2.

- Mayer, Hans Eberhard. The Crusades. John Gillingham, translator. Oxford: 1988. ISBN 0-19-873097-7.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. University of Pennsylvania: 1991. ISBN 0-8122-1363-7.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan, editor. The Oxford History of the Crusades. Oxford: 2002. ISBN 0-19-280312-3.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The First Crusaders, 1095–1131. Cambridge: 1998. ISBN 0-521-64603-0.

- Runciman, Steven. A History of the Crusades: Volume 1, The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge: 1987 ISBN 0-521-34770-X

- Setton, Kenneth, editor. A History of the Crusades. Madison: 1969–1989 (available online).

- Magdalino, Paul, "The Byzantine Background to the First Crusade" (available online)

Bibliographies

- Bibliography of the First Crusade (1095–1099) compiled by Alan V. Murray, Institute for Medieval Studies, University of Leeds. Extensive and up to date as of 2004.