This is an old revision of this page, as edited by TruHeir (talk | contribs) at 22:41, 6 April 2009. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:41, 6 April 2009 by TruHeir (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Nubia" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Nubia (Template:PronEng) is a region in Southern Egypt along the Nile and in what is now northern Sudan. Most of Nubia is situated in Sudan with about a quarter of its territory in Egypt. In ancient times it was an independent kingdom.

While the ancient kingdoms of Nubia had changing boundaries, modern Nubia is roughly thought of as the region along the Nile, south of Aswan, up to the Fourth Cataract of the Nile in Sudan.

Recent studies in population genetics suggest that there has been a significant south-to-north gene flow through the Nile Valley. Hence, no significant evidence exists to support the claim that the Nubians are recent immigrants from elsewhere in Sudan or Egypt. For example a recent study that extracted the remains of a 2,000-year-old Nubian mummy showed no significant genetic variations with contemporary Nubians. The present-day Nuba populations of Kordofan adopted the Nubian dialect sometime during Nubia's Medieval period when the Nubian kingdoms (from Nile Valley) expanded to the southwest. Consequently, the Nubian language and culture was adopted by the local populations of Kordofan, who later became known as "Nuba", i.e., after the "Nubians".

Etymology and language

A large variety of languages are spoken in the Nubia region due to its long history of organized civilizations and external migrations. For instance, the Nilo-Saharan subfamily including Nobiin, Kenuzi-Dongola, Midob and several related varieties is present. An offshoot of this group, Birgid was also spoken (at least until 1970) north of Nyala in Darfur, but is now extinct. Historically prominent is Old Nubian, which was used in mostly religious texts dating from the 8th and 9th centuries AD, and is considered ancestral to modern day Nobiin..

History

Pre-history

By the 100th millennium BC, the peoples who inhabited what is now called Nubia, were full participants in the Neolithic revolution. Saharan rock reliefs depict scenes that have been thought to be suggestive of a cattle cult, typical of those seen throughout parts of Eastern Africa and the Nile Valley even to this day. The first settled colonies and cultures are though to have inhabited Nubia in what is now the Sudan as far back as 6000 BCE. The Nubians were conquered by the Egyptians during the reign of Kush. Megaliths discovered at Nabta Playa are early examples of what seems to be the world's first Archaeoastronomy devices, predating Stonehenge by at least 1000 years. This complexity, as observed at Nabta Playa, and as expressed by different levels of authority within the society there, likely formed the basis for the structure of both the Neolithic society at Nabta and the Old Kingdom of Egypt.

Around 3800 B.C., the first "Nubian" culture arose, termed the A-Group, and it was contemporary, ethnically, and culturally very similar to the polities in predynastic Naqadan Upper Egypt.

According to F.A. Hassan, the Neolithic in the Nile valley likely came from the Sudan, as well as the Sahara, and there was shared culture with the two areas and with that of Egypt during this time period.

Around 3300 BC, there is evidence of a unified kingdom, as shown by the finds at Qustul, that maintained substantial interactions (both cultural and genetic) with the culture of Naqadan, Upper Egypt, and even contributed to the unification of the Nile valley, and very likely contributed some pharaonic iconography, such as the white crown and serekh, later to be used by the famous Egyptian pharaohs.. Around the turn of the protodynastic period, Naqada, in its bid to conquer and unify the whole Nile valley, seems to have conquered Ta-Seti (the kingdom where Qustul was located) and harmonized it with the Egyptian state, and thus it became the first nome of Upper Egypt.

By this time, in addition to its political importance, Nubia had become a vital trade route for Egypt, providing a corridor between Egypt and tropical Africa. This can be seen by 3100 BC, a period when Egyptian craftsmen were able to use ivory, ebony, and special woods that came through Nubia from tropical Africa.

However, the A-Group began to decline in the early twenty-eighth century BC. The succeeding era's culture is known as B-Group. Previously, the B-Group people were thought to have invaded from elsewhere. Today, most historians believe that B-Group was merely A-Group, but far less developed. The causes of this are uncertain, but one theory holds that it was caused by Egyptian invasions and pillaging that began at this time.

Early history

Nubia is the homeland of one of Africa's earliest black civilization, with a history which can be traced from 2000 B.C. onward through Nubian monuments and artifacts as well as written records from Egypt and Rome. In antiquity, Nubia was a land of great natural wealth, of gold mines, ebony, ivory and incense which was always prized by her neighbors.

Old Kingdom Egyptian accounts of trade missions first mentioned Nubia in 2300 BC. Egyptians imported gold, incense, ebony, ivory, and exotic animals from tropical Africa through Nubia. Aswan, right above the First Cataract, marked the southern limit of Egyptian control. As trade between Egypt and Nubia increased, so did wealth and stability.

By the sixth dynasty of Egypt, Nubia was divided into a series of small kingdoms. Scholars debate whether these C-Group peoples, who flourished from c. 2240 BC to c. 2150 BC, were another internal evolution from the B-Group, or invaders. There are definite similarities between the pottery of A-Group and C-Group, so it may be a return of the ousted Group-As, or an internal revival of lost arts. The Sahara Desert was becoming too arid to support human beings. These may have been a sudden influx of Saharan nomads. C-Group pottery was characterized by all-over incised geometric lines with white infill and impressed imitations of basketry.

A contemporaneous, but distinct, culture from the C-Group was the Pan Grave culture, so called because of their shallow graves. Shallow graves produced mummies naturally. The Pan Graves are associated with the East bank of the Nile, but the Pan Graves and C-Group definitely interacted. Their pottery is characterized by incised lines of a more limited character than those of the C-Group. It generally had interspersed undecorated spaces within the geometric scheme.

During this period, trade with Egypt continued and during the Egyptian Middle Kingdom (c. 2040–1640 BC), Egypt began expanding into Nubia to gain more control over the trade routes in Northern Nubia and direct access to trade with Southern Nubia. They erected a chain of forts down the Nile below the Second Cataract. These garrisons seemed to have peaceful relations with the local Nubian people, but little interaction during the period.

From the C-Group culture, the Kingdom of Kerma arose as the first kingdom to unify much of the region. It was named for its presumed capital at Kerma, one of the earliest urban centers in tropical Africa. By 1750 BC, the kings of Kerma were powerful enough to organize the labor for monumental walls and structures of mud brick. They created rich tombs with possessions for the afterlife and large human sacrifices. The craftsmen were skilled in metalworking and their pottery surpassed in skill that of Egypt. Reisner excavated sites at Kerma and found large tombs and a palace-like structure ('Deffufa'), alluding to the early stability in the region. By 1650 BC, Kerma had become powerful enough to administer the entire area between the 1st and 4th Cataracts of the Nile.

However, relations with Egypt were apparently tense at times and at one point around 1550 BC, Kerma defeated Egypt in a major battle, with Egypt suffering a "humiliating defeat" by the hands of the Nubians. According to Davies, head of the joint British Museum and Egyptian archaeological team which discovered evidence of this battle, the attack was so devastating that, had the Kerma forces chosen to stay and occupy Egypt, they might have been able to destroy Egyptian civilization.

Yet soon afterward, Egypt's power was revived under the New Kingdom (c. 1532–1070 BC) and Egypt began to expand farther southward. Destroying the kingdom and capital of Kerma, Egyptians expanded to the Fourth Cataract. By the end of the reign of Thutmose I in 1520 BC, Egyptians had annexed all of northern Nubia. They built a new administrative center at Napata, and used the area to produce gold. This made Egypt the prime source of gold in Africa and the Middle East during the New Kingdom.

In the late 12th century, though, Egyptian power was in decline and by 1070 BC the New Kingdom fell and Egyptian administration in Nubia came to an end. With this opening, local Nubian rulers reasserted themselves.

Kush

Main article: KushWhile Egyptian forces pulled out by the 11th century, they left a lasting legacy. A merger with indigenous customs can be seen in many of the practices formed during the kingdom of Kush. Archaeologists have found several burials which seem to belong to local leaders, buried here soon after the Egyptians decolonized the Nubian frontier. Kush adopted many Egyptian practices, such as their religion and the practice of building pyramids.

However, Kushite power soon overshadowed Egyptian. In the 8th century BC, under the leadership of king Piye, Kush invaded and controlled Egypt itself for a period (the Ethiopian dynasty). Kushite kings would hold sway over their northern neighbors for nearly one hundred years. Of the Nubian kings of this era, Taharqa is perhaps the best known. A son and the third successor of King Piye, Taharqa was crowned king in c.690 in Memphis. He ruled over both Nubia and Egypt and devoted himself to all kinds of peaceful works, like the restoration of ancient temples in both Egypt and Nubia and building new sanctuaries, like the one at Kawa. In February/March 673, an army sent by the Assyrian king Esarhaddon was defeated by the Egyptians, but this was the last of Egyptian successes. In April 671, the Assyrians were back, and this time, they captured Memphis (11 July). Taharqa had left the city, but his brother and son were taken prisoner.

In Lower Egypt, Esarhaddon appointed the native princes as governors. One of these was Necho I, a descendant of Tefnakht, who resided in Sais in the western Delta. Meanwhile, Taharqo fought back, reoccupied in Memphis in 669, and forced the princes into submission.

This provoked a third Assyrian campaign, which was broken off because Esarhaddon died. He was succeeded by Ashurbanipal, who conducted the fourth campaign in 667/666, took Memphis, and sacked Thebes. Because the princes were obviously unreliable, the Assyrian king chose one of them who could be trusted: Necho. When, after Taharqo's death in 664, his successor Tanwetamani tried to reconquer Memphis (the subject of the Dream Stela), Necho beat him, and although he was killed in action, power remained in his family. It was his son Psammetichus I, who unified Egypt, and was clever enough to give the Assyrians the impression that he still served them once they had been forced to recall their garrisons when civil war broke out in Assyria (651-648). The sphinx of Taharqa was found at Kawa Sudan, and is now on display in the British Museum.

Meroë

Meroë (800 BC – c. AD 350) lay on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, approximately 200 km north-east of Khartoum. There the people preserved many ancient Egyptian customs, but their culture was unique in many respects. They developed their own form of writing, first using Egyptian hieroglyphs, and later creating an alphabetic script with twenty-three signs. Meroe leaders had many pyramids built during this period. The kingdom maintained an impressive standing military force.

Alexander the Great heading his forces in 332 BC with the intent to conquer the mineral-rich region. According to descriptions of the event, he was confronted with the brilliant military formation of their warrior queen, Candace of Meroë, who was leading the army from atop an elephant, and Alexander concluded it would be best to withdraw his forces. Following the withdrawal, he turned his army toward Egypt, which he conquered without resistance, and he never made another attempt to enter Nubia. This story is one that comes from the fictionalized Alexander Romance and is thought to be legendary; indeed, historical accounts show that Alexander never invaded Nubia and did not attempt to move further south than the oasis of Siwa in Egypt.

Strabo describes a similar clash with the Romans, in which the Roman army fought Nubian archers under the leadership of another Kentake. This queen was described as "one-eyed", being blind in one eye. The strategic formations used by this second queen are well documented in Strabo's description. After her initial victory when she attacked Roman territory, she was defeated and surrendered. She succeeded in negotiating a peace treaty on favourable terms. The kingdom of Meroë began to fade as a power by the first or second century AD, sapped by the war with the Roman province of Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries. Eventually Meroë was defeated by a new rising kingdom to their south, Aksum, under King Ezana of Axum.

Christian Nubia

Around 350 AD the area was invaded by the Eritrean and Ethiopian kingdom of Aksum and the kingdom collapsed. Eventually three smaller kingdoms replaced it: northernmost was Nobatia between the first and second cataract of the Nile River, with its capital at Pachoras (modern day Faras); in the middle was Makuria, with its capital at Old Dongola; and southernmost was Alodia, with its capital at Soba (near Khartoum).

King Silko of Nobatia crushed the Blemmyes, and recorded his victory in a Greek inscription carved in the wall of the temple of Talmis (modern Kalabsha) around AD 500.

While bishop Athanasius of Alexandria consecrated one Marcus as bishop of Philae before his death in 373, showing that Christianity had penetrated the region by the fourth century, John of Ephesus records that a Monophysite priest named Julian converted the king and his nobles of Nobatia around 545. John of Ephesus also writes that the kingdom of Alodia was converted around 569. However, John of Bisclorum records that the kingdom of Makuria was converted to Roman Catholicism the same year, suggesting that John of Ephesus might have been mistaken. Further doubt was cast on John's testimony by an entry in the chronicle of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria Eutychius, which stated that in 719, the church of Nubia transferred its allegiance from the Greek Orthodox to the Coptic Church.

By the 7th century Makuria expanded and became the dominant power in the region. It was strong enough to halt the southern expansion of Islam after the Arabs had taken Egypt. After several failed invasions, the new rulers in Egypt agreed to a treaty with Dongola to allow for peaceful coexistence and trade. This treaty held for six hundred years. Over time the influx of Arab traders introduced Islam to Nubia. Islam gradually supplanted Christianity.

As Mamluks dominated the area in 1315, and appointed a Nubian Prince who converted to Islam, conversions to Islam proceeded. While there are records of a bishop at Qasr Ibrim in 1372, his see had come to include that located at Faras. Archeological evidence demonstrates that by 1350, the "Royal" church at Dongola had been converted to a mosque.

Modern Nubia

Main article: Nubian people

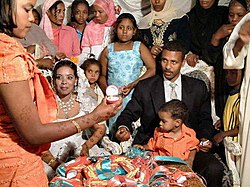

The influx of Arabs and Nubians to Egypt and Sudan had contributed to the suppression of the Nubian identity following the collapse of the last Nubian kingdom in 1900. A major part of the modern Nubian population were totally arabized and some claimed to be Arabs (Jaa'leen—the majority of Northern Sudanese—and some Donglawes in Sudan, Kenuz and Koreskos in Egypt). However all Nubians were converted to Islam, and Arabic language became their main media of communication in addition to their indigenous old Nubian language. The unique characteristic of Nubian is shown in their culture (dress, dances, traditions, and music) as well as their indigenous language which is the common feature of all Nubians

In the 14th century the Dongolan government collapsed and the region became divided and dominated by Egypt. The region was invaded frequently during the next centuries. A number of smaller kingdoms were established for limited periods. In the sixteenth century, Egypt gained control of Northern Nubia, while the Kingdom of Sennar took over much of the south.

During the rule of Mehemet Ali in the early nineteenth century, Egypt took control over the entire Nubian region. Later it became a joint Anglo-Egyptian condominium. With the end of colonialism in the 20th century, the territory of Nubia was divided between Egypt and Sudan.

Many Egyptian Nubians were forcibly resettled to make room for Lake Nasser after the construction of the dams at Aswan. Nubian villages can now be found north of Aswan on the west bank of the Nile and on Elephantine Island, and many Nubians live in large cities such as Cairo. Egyptian Nubians tend to be far more socio-economically disadvantaged within Egypt, than Sudanese Nubians in Sudan.

See also

- List of monarchs of Kush

- Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt

- Nubiology

- Nubian languages

- Pyramids of Nubia

- Aida

- Kush

- Kentakes

- Meroë

Notes and references

Notes

- "History of Nubia." Accessed on 2008-10-10. From the Nubia Museum.

- M Krings, A E Salem, K Bauer, H Geisert, A K Malek, L Chaix, C Simon, D Welsby, A Di Rienzo, G Utermann, A Sajantila, S Pääbo, and M Stoneking, mtDNA analysis of Nile River Valley populations: A genetic corridor or a barrier to migration? Am J Hum Genet. 1999 April; 64(4): 1166–76.

- Note 2 above at page 1175.

- Derek A. Welsby, The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia: Pagans, Christians and Muslims on the Middle Nile (British Museum Press, 2002)

- History of Nubia

- Sudan, 8000–2000 b.c.

- PlanetQuest: The History of Astronomy — Retrieved on 2007-08-29

- Late Neolithic megalithic structures at Nabta Play, by Fred Wendorf (1998).

- Hunting for the Elusive Nubian A-Group People, by Maria Gatto, archaeology.org

- "Further Studies of Crania From Ancient Northern Africa: An Analysis of Crania From First Dynasty Egyptian Tombs, Using Multiple Discriminant Functions" (PDF). — American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 87: 245–54 (1992)

- "Studies of Ancient Crania From Northern Africa" (PDF). — S.O.Y. Keita, American Journal of Physical Anthropology (1990)

- "Forbears of Menes in Nubia: Myth or Reality" (PDF). — Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Jan., 1987), pp. 15–26

- Egypt and Sub-Saharan Africa: Their Interaction — Encyclopedia of Precolonial Africa, by Joseph O. Vogel, AltaMira Press, (1997), pp. 465–72

- History of Nubia, Dr. Stuart Tyson. Accessed 10-10-2008.

- Tomb Reveals Ancient Egypt's Humiliating Secret The Times (London, 2003)

- Meroë: writing — digitalegypt

- Jones, David E., Women Warriors: A History, Inc.; (2000)

- ^ Gutenberg, David M. (2003). The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton University Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Morgan, J.R. and Stoneman, Richard (1994). Greek Fiction: The Greek Novel in Context. Routledge. pp. p.117–118. ISBN 0415085071.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nubian Queens in the Nile Valley and Afro-Asiatic Cultural History — Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, Professor of Anthropology, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston U.S.A, August 20–26, 1998

- http://www.jstor.org/pss/716999

- African Affairs — Sign In Page

- The Story of Africa| BBC World Service

References

- Black Pharaohs - National Geographic Feb 2008

- Thelwall, Robin (1978) 'Lexicostatistical relations between Nubian, Daju and Dinka', Études nubiennes: colloque de Chantilly, 2–6 juillet 1975, 265–286.

- Thelwall, Robin (1982) 'Linguistic Aspects of Greater Nubian History', in Ehret, C. & Posnansky, M. (eds.) The Archeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History. Berkeley/Los Angeles, 39–56.

- Bulliet et al. (2001) 'Nubia,' The Earth and Its Peoples, pp. 70–71, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

External links

- http://www.napata.org

- Kerma excavation

- Template:Fr icon Voyage au pays des pharaons noirs. Travel in Sudan: pictures and notes on the nubian history

- Racism and the Rediscovery of Ancient Nubia

- Merowiki

- NUBIAN CHRISTIANITY: THE NEGLECTED HERITAGE