This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 128.243.220.21 (talk) at 08:26, 28 May 2009. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 08:26, 28 May 2009 by 128.243.220.21 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the English as an ethnic group and nation. For information on the population of England, see Demography of England. For other uses, see English (disambiguation). Ethnic group Alfred the Great • W. Shakespeare • G. Stephenson • D. Albarn Elizabeth I • N. Gwyn • J. Austen • K. Winslet | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 90,000,000 worldwide | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 45.26 million (estimate) | |

| 28,410,295 | |

| 6,570,015 | |

| 6,358,880 | |

| 44,202 - 281,895 | |

| Languages | |

| English | |

| Religion | |

| Traditionally Christianity, mostly Anglicanism, but also non-conformists (see History of the Church of England) and also Roman Catholics (see Catholic Emancipation). Minority Islam, Hinduism, Judaism and others (See Religion in England). | |

The English (from Template:Lang-ang) are a nation and ethnic group native to England who speak English. The English identity as a people is of early medieval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn.

The largest single English population reside in England, a constituent country of the United Kingdom. They are a mixture of several closely related groups that have settled in what became England, such as the Angles, Saxons, Norse Vikings and Normans.

This group forms the largest part of the racially-based classification used in the 2001 UK census known as White British. More recent migrations to England include peoples from a variety of different regions of Great Britain and Ireland and many other countries, mostly from Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and Commonwealth countries. Some of these more recent migrants and their descendants have assumed a solely British or English identity, while others have developed dual or hyphenated identities.

Definitions

Writing about the English may be complicated because England has historically been settled by waves of invaders and immigrants at different periods in history, and has also spread its influence, and its populace, worldwide. Hence, the English can be considered to be an ethnic group that shares a belief in their common descent from a mass migration of Germanic peoples (usually referred to as Anglo-Saxons) during the sub-Roman period. Historian Catherine Hills describes what she calls the "national origin myth" of the English:

- The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons ... is still perceived as an important and interesting event because it is believed to have been a key factor in the identity of the present inhabitants of the British Isles, involving migration on such a scale as to permanently change the population of south-east Britain, and making the English a distinct and different people from the Celtic Irish, Welsh and Scots.....this is an example of a national origin myth... and shows why there are seldom simple answers to questions about origins.

The English can be viewed in a variety of different ways, but the broadest concept comprises anyone who considers themselves English and are considered English by most other people.

English nationality

Although England is no longer an independent nation state, but rather a constituent country within the United Kingdom, the English may still be regarded as a "nation" according to the Oxford English Dictionary's definition: a group united by factors that include "language, culture, history, or occupation of the same territory".

The concept of an 'English nation' is older than that of the 'British nation' and the 1990s witnessed a revival in English self-consciousness. This is linked to the expressions of national self-awareness of the other British nations of Wales and Scotland — which take their most solid form in the new devolved political arrangements within the United Kingdom — and the waning of a shared British national identity as the British Empire fades into history.

While expressions of English national identity can involve beliefs in common descent, most political English nationalists do not consider Englishness to be a form of kinship. For example, the English Democrats Party states that "We do not claim Englishness to be purely ethnic or purely cultural, but it is a complex mix of the two. We firmly believe Englishness is a state of mind", while the Campaign for an English Parliament says, "The people of England includes everyone who considers this ancient land to be their home and future regardless of ethnicity, race, religion or culture". In an article for The Guardian, novelist Andrea Levy (born in London to Jamaican parents) calls England a separate country "without any doubt" and asserts that she is "English. Born and bred, as the saying goes. (As far as I can remember, it is born and bred and not born-and-bred-with-a-very-long-line-of-white-ancestors-directly-descended-from-Anglo-Saxons.)" Arguing that "England has never been an exclusive club, but rather a hybrid nation", she writes that "Englishness must never be allowed to attach itself to ethnicity. The majority of English people are white, but some are not ... Let England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland be nations that are plural and inclusive."

However, this use of the word "English" is complicated by the fact that most non-white people in England identify as British rather than English. In their 2004 Annual Population Survey, the Office of National Statistics compared the ethnic identities of British people with their perceived national identity. They found that while 58% of white people described their nationality as "English", the vast majority of non-white people called themselves "British". For example, "78 per cent of Bangladeshis said they were British, while only 5 per cent said they were English, Scottish or Welsh", and the largest percentage of non-whites to identify as English were the people who described their ethnicity as "Mixed" (37%).

English ethnicity

It is difficult to clearly define the origins of the English, owing to the close interactions between the English and their neighbours in the British Isles, and the waves of immigration that have added to England's population at different periods. The conventional view of English origins is that the English are primarily descended from the Anglo-Saxons and other Germanic tribes that migrated to Great Britain following the end of the Roman occupation of Britain, with assimilation of later migrants such as the Vikings and Normans. This version of history is considered by some historians and geneticists as simplistic or even incorrect. However, the notion of the Anglo-Saxon English has traditionally been important in defining English identity and distinguishing the English from their Celtic neighbours, such as the Scots, Welsh and Irish. Furthermore, the idea of an English Anglo-Saxon origin is important to those who see differences between people with long-standing English ancestry and people whose ancestors arrived much more recently, an ethno-nationalistic attitude expressed succinctly by a character in Sarah Kane's play Blasted who boasts "I'm not an import", contrasting himself with the children of immigrants: "they have their kids, call them English, they're not English, born in England don't make you English".

A popular interest in English identity is evident in the recent reporting of scientific and sociological investigations of the English, in which their complex results are heavily simplified. In 2002, the BBC used the headline "English and Welsh are races apart" to report a genetic survey of test subjects from market towns in England and Wales, while in September 2006, The Sunday Times reported that a survey of first names and surnames in the UK had identified Ripley in Derbyshire as "the 'most English' place in England with 88.58% of residents having an English ethnic background". The Daily Mail printed an article with the headline "We're all Germans! (and we have been for 1,600 years)". In all these cases, the conclusions of these studies have been exaggerated or misinterpreted, with the language of race being employed by the journalists. In addition, several recent books, including those of Stephen Oppenheimer and Brian Sykes, have argued that the recent genetic studies in fact do not show a clear dividing line between the English and their 'Celtic' neighbours, but that there is a gradual clinal change from west (primarily Iberian origin with some genetic ties to Altaic peoples) to east (primarily Iberian and Balkan origin from the "Balkan refuge"). They suggest that the majority of the ancestors of British peoples were the original paleolithic settlers of Great Britain, and that the differences that exist between the east and west coasts of Great Britain though not large, are deep in prehistory, mostly originating in the upper paleolithic and mesolithic (15,000-7,000 years ago).

Relatedly, studies of people with English ancestry have shown that they tend not to regard themselves as an 'ethnic group', even when they live in other countries. Patricia Greenhill studied people in Canada with English heritage, and found that they did not think of themselves as "ethnic", but rather as "normal" or "mainstream", an attitude Greenhill attributes to the cultural dominance of the English in Canada.

Population

It is unclear how many people in the UK consider themselves English. In the 2001 UK census, respondents were invited to state their ethnicity, but while there were tick boxes for 'Irish' and for 'Scottish', there were none for 'English' or 'Welsh', who were subsumed into the general heading 'White British'. Following complaints about this, the 2011 census will "allow respondents to record their English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, Irish or other identity."

Relationship to Britishness

Another complication in defining the English is a common tendency for the words "English" and "British" to be used interchangeably. In his study of English identity, Krishan Kumar describes a common slip of the tongue in which people say "English, I mean British". He notes that this slip is normally made only by the English themselves and by foreigners: "Non-English members of the United Kingdom rarely say 'British' when they mean 'English'". Kumar suggests that although this blurring is a sign of England's dominant position with the UK, it is also "problematic for the English when it comes to conceiving of their national identity. It tells of the difficulty that most English people have of distinguishing themselves, in a collective way, from the other inhabitants of the British Isles".

This tendency may be on the wane. In 1965, the historian A. J. P. Taylor wrote,

- "When the Oxford History of England was launched a generation ago, "England" was still an all-embracing word. It meant indiscriminately England and Wales; Great Britain; the United Kingdom; and even the British Empire. Foreigners used it as the name of a Great Power and indeed continue to do so. Bonar Law, a Scotch Canadian, was not ashamed to describe himself as "Prime Minister of England" Now terms have become more rigorous. The use of "England" except for a geographic area brings protests, especially from the Scotch."

However, although Taylor believed this blurring effect was dying out, in his 1999 book The Isles, Norman Davies lists numerous examples in history books of "British" still being used to mean "English" and vice versa.

Writer Paul Johnson has suggested that like most dominant groups, the English have only demonstrated interest in their ethnic self-definition when they were feeling oppressed.

History of English identity

Further information: ]| Part of a series on |

| English people |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| Music |

| Language |

| Cuisine |

| Dance |

| Religion |

| People |

| Diaspora |

Overview

Further information: Genetic history of the British Isles and Settlement of Great Britain and Ireland"English" is not used to refer to the earliest inhabitants of the area that would become England - Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, Celtic Britons, and Roman colonists, the same applies to the "Irish", "Welsh" and "Scots". This is because up to and during the Roman occupation of Britain, the region now called England was not a distinct country; all the native inhabitants of Britain spoke Brythonic languages and were regarded as Britons (or Brythons) divided into many tribes. The word "English" refers to a heritage that began with the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in the 5th century, who settled lands already inhabited by Romano-British tribes. That heritage then comes to include later arrivals, including Scandinavians, Normans, as well as those Romano-Britons who still lived in England.

Although it should be noted that there is no historical evidence that the Celts, Britons or Vikings were ever singular ethnic groups in England and never acted as such. Ancient Britain had numerous tribes under different leaders and also a lack of documentational evidence that they saw themselves as one ethnic group. Viking raids and settlement were not a singular event by one ethnic group and similarities between Scandinavians and English speakers both culturally and linguistically would mean an easy adoption of local identities. Scandinavian elements for example can be found in Beowulf and Sutton Hoo prior to the Vikings, so distinguishing what is Viking and what is pre-Scandinavian Viking elements can prove difficult. Lack of written documentation at the time particularly in areas outside Wessex can make any assumptions about language and ethnicity or identity impossible. Although the term Anglo-Saxon was used in the early Medieval Ages there is no evidence that the people of England referred themselves as such and due to the hierarchical nature of Anglo-Saxon society, maintaining other identities would have proved difficult as all groups would have had to become part of the overall Anglo-Saxon system. Recent DNA evidence also shows that far from mass migrations, genetically the 'English' like most of Europe originate in the Paleolithic and Neolithic and very little DNA has been contributed from the Roman period onwards. Germanic contributions to England culturally and linguistically however shouldn't however be underestimated and there is evidence to suggest some of this influence could pre-date either Anglo-Saxons or Vikings.

Sub-Roman Britain and Anglo-Saxon England

Further information: ] Further information: Genetic history of the British IslesThe first people to be called 'English' were the Anglo-Saxons, a group of closely related Germanic tribes that began migrating to eastern and southern Great Britain, from southern Denmark and northern Germany, in the 5th century AD, after the Romans had withdrawn from Britain. The Anglo-Saxons gave their name to England (Angle-land) and to the English.

The Anglo-Saxons arrived in a land that was already populated by people commonly referred to as the 'Romano-British'—the descendants of the native Brythonic-speaking population that lived in the area of Britain under Roman rule during the 1st-5th centuries AD. The multi-ethnic nature of the Roman Empire meant that small numbers of other peoples may have also been present in England before the Anglo-Saxons arrived: for example, archaeological discoveries suggest that North Africans may have had a limited presence.

The exact nature of the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons and their relationship with the Romano-British is a matter of debate. Traditionally, it was believed that a mass invasion by various Anglo-Saxon tribes largely displaced the indigenous British population in southern and eastern Great Britain (modern day England with the exception of Cornwall). This was supported by the writings of Gildas, the only contemporary historical account of the period, describing slaughter and starvation of native Britons by invading peoples (aduentus Saxonum). Added to this was the fact that the English language contains no more than a handful of words borrowed from Brythonic sources (although the names of some towns, cities, rivers etc do have Brythonic or pre-Brythonic origins, becoming more frequent towards the west of Britain). However, this view has been re-evaluated by some archaeologists and historians in recent times, more recently supported by genetic studies, who claim to only find minimal evidence for mass displacement: archaeologist Francis Pryor has stated that he "can't see any evidence for bona fide mass migrations after the Neolithic." Historian Malcolm Todd writes

- "It is much more likely that a large proportion of the British population remained in place and was progressively dominated by a Germanic aristocracy, in some cases marrying into it and leaving Celtic names in the, admittedly very dubious, early lists of Anglo-Saxon dynasties. But how we identify the surviving Britons in areas of predominantly Anglo-Saxon settlement, either archaeologically or linguistically, is still one of the deepest problems of early English history."

Viking raids and formation of the Danelaw

Further information: ]From about AD 800 waves of Danish Viking assaults on the coastlines of the British Isles were gradually followed by a succession of Danish settlers in England. At first, the Vikings were very much considered a separate people from the English. This separation was enshrined when Alfred the Great signed the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum to establish the Danelaw, a division of England between English and Danish rule, with the Danes occupying northern and eastern England. However, Alfred's successors subsequently won military victories against the Danes, incorporating much of the Danelaw into the nascent kingdom of England. Danish invasions continued into the 11th century, and there were both English and Danish kings in the period following the unification of England (for example, Ethelred the Unready was English but Canute the Great was Danish).

Gradually, the Danes in England came to be seen as 'English'. They had a noticeable impact on the English language: many English words, such as dream, take, they and them are of Old Norse origin, and place names that end in -thwaite and -by are Scandinavian in origin.

The unification of England

Further information: ]

The English population was not politically unified until the 10th century. Before then, it consisted of a number of petty kingdoms which gradually coalesced into a Heptarchy of seven powerful states, the most powerful of which were Mercia and Wessex. The English nation state began to form when the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms united against Danish Viking invasions, which began around 800 AD. Over the following century and a half England was for the most part a politically unified entity, and remained permanently so after 959.

The nation of England was formed in 937 by Athelstan of Wessex after the Battle of Brunanburh, as Wessex grew from a relatively small kingdom in the South West to become the founder of the Kingdom of the English, incorporating all Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and the Danelaw.

Norman and Angevin rule

The Norman Conquest of 1066 brought Anglo-Saxon and Danish rule of England to an end, as the new Norman elite almost universally replaced the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy and church leaders. After the conquest, "English" normally included all natives of England, whether they were of Anglo-Saxon, Scandinavian or Celtic ancestry, to distinguish them from the Norman invaders, who were regarded as "Norman" even if born in England, for a generation or two after the Conquest. The Norman dynasty ruled England for 87 years until the death of King Stephen in 1154, when the succession passed to Henry II, House of Plantagenet (based in France), and England became part of the Angevin Empire until 1399.

Various contemporary sources suggest that within fifty years of the invasion most of the Normans outside the royal court had switched to English, with Anglo-Norman remaining the prestige language of government and law largely out of social inertia. For example, Orderic Vitalis, a historian born in 1075 and the son of a Norman knight, said that he learned French only as a second language. Anglo-Norman continued to be used by the Plantagenet kings until Edward I came to the throne. Over time the English language became more important even in the court, and the Normans were gradually assimilated, until, by the 14th Century, both rulers and subjects regarded themselves as English and spoke the English language.

Despite the assimilation of the Normans, the distinction between 'English' and 'French' survived in official documents long after it had fallen out of common use, in particular in the legal phrase Presentment of Englishry (a rule by which a hundred had to prove an unidentified murdered body found on their soil to be that of an Englishman, rather than a Norman, if they wanted to avoid a fine). This law was abolished in 1340.

The English and Britain

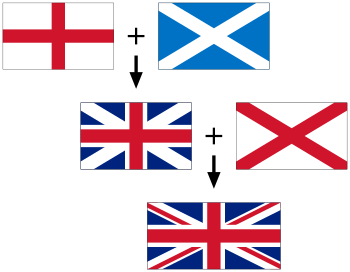

St George's Cross

St George's Cross (England) St Andrew's Cross

(Scotland) Great Britain St Patrick's Cross

(Ireland) United Kingdom Main articles: United Kingdom and English nationalism

Since the 16th century, England has been one part of a wider political entity covering all or part of the British Isles, which is today called the United Kingdom. Wales was annexed by England by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, which incorporated Wales into the English state. A new British identity was subsequently developed when James VI of Scotland became James I of England as well and expressed the desire to be known as the monarch of Britain. In 1707, England formed a union with Scotland by the passage of the Acts of Union 1707 in both the Scottish and English parliaments, creating the Kingdom of Great Britain. In 1801 another Act of Union formed a union between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. About two thirds of Irish population, (those who lived in 26 of the 32 counties of Ireland) left the United Kingdom in 1922 to form the Irish Free State, and the remainder became the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Throughout the history of the UK, the English have been dominant in terms of population and political weight. As a consequence, notions of 'Englishness' and 'Britishness' are often very similar. At the same time, after the 1707 Union, the English, along with the other peoples of the British Isles, have been encouraged to think of themselves as British rather than identifying themselves by the smaller constituent nations.

Recent migration

- See also: Historical immigration to Great Britain, Immigration to the United Kingdom (1922-present day), Demographics of England, British Asian, Black British.

Although England has not been successfully conquered since the Norman conquest or extensively settled since prior to that, it has been the destination of varied numbers of migrants at different periods from the seventeenth century. While some members of these groups maintain a separate ethnic identity, others have assimilated and intermarried with the English. Since Oliver Cromwell's resettlement of the Jews in 1656, there have been waves of Jewish immigration from Russia in the nineteenth century and from Germany in the twentieth. After the French king Louis XIV declared Protestantism illegal in 1685 with the Edict of Fontainebleau, an estimated 50,000 Protestant Huguenots fled to England. Due to sustained and sometimes mass emigration from Ireland, current estimates indicate that around 6 million people in the UK have at least one grandparent born in the Republic of Ireland.

There has been a black presence in England since at least the 16th century due to the slave trade and an Indian presence since the mid 19th century because of the British Raj. Black and Asian proportions have grown in England as immigration from the British Empire and the subsequent Commonwealth of Nations was encouraged due to labour shortages during post-war rebuilding. In 2006, an estimated 591,000 migrants arrived to live in the UK for at least a year, while 400,000 people emigrated from the UK for a year or more. The largest group of arrivals was people from the Indian subcontinent. While one result of this immigration has been incidents of racial tension and/or hatred, such as the Brixton and Bradford riots, there has also been considerable intermarriage; the 2001 census recorded that 1.31% of England's population call themselves "Mixed", and The Sunday Times reported in 2007 that mixed race people are likely to be the largest ethnic minority in the UK by 2020.

Resurgent English nationalism

The late 1990s saw a resurgence of English national identity, spurred by devolution in the 1990s of some powers to the Scottish Parliament, National Assembly for Wales and the Northern Ireland Assembly. As England lacks its own devolved parliament, its laws are created only in the UK parliament, giving rise to the "West Lothian question", a hypothetical situation in which a law affecting only England could be voted for or against by a Scottish MP. Consequently, groups such as the Campaign for an English Parliament are calling for the creation of a devolved English Parliament, claiming that there is now a discriminative democratic deficit against the English. A rise in English self-consciousness has resulted, with increased use of the English flag.

The England Society was formed in 2005 to promote Englishness as a cultural and civic notion rather than a political or religious one. The Society promotes itself via a number of campaigns, mostly web-based and has a membership as of October 2008 of around 800 registered members.

The English nationalist movement has had mixed results. Opinion polls show support for a devolved English parliament from about two thirds of the residents of England as well as support from both Welsh and Scottish nationalists. Conversely, the English Democrats gained just 14,506 votes in the 2005 UK general election.

Geographic distribution

From the earliest times English people have left England to settle in other parts of the British Isles, but it is not possible to identify their numbers, as British censuses have historically not invited respondents to identify themselves as English. However, the census does record place of birth, revealing that 8.08% of Scotland's population, 3.66% of the population of Northern Ireland and 20% of the Welsh population were born in England. Similarly, the census of the Republic of Ireland does not collect information on ethnicity, but it does record that there are over 200,000 people living in Ireland who were born in England and Wales.

English diaspora

Further information: English American, English Canadian, English Chilean, Anglo-African, English Australian, and New Zealand EuropeanEnglish emigrant and ethnic descent communities are found across the world, and in some places, settled in significant numbers. Substantial populations descended from English colonists and immigrants exist in the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand.

In the 2000 United States Census, 24,509,692 Americans described their ancestry as wholly or partly English. In addition, 1,035,133 recorded British ancestry. In the 1980 United States Census 50 million Americans claimed English ancestry.

In the 2006 Canadian Census, 'English' was the most common ethnic origin (ethnic origin refers to the ethnic or cultural group(s) to which the respondent's ancestors belong) recorded by respondents; 6,570,015 people described themselves as wholly or partly English, 16% of the population. On the other hand people identifying as Canadian but not English may have previously identified as English before the option of identifying as Canadian was available.

In Australia, the 2006 Australian Census recorded 6,298,945 people who described their ancestry, but not ethnicity, as 'English'. 1,425,559 of these people recorded that both their parents were born overseas.

Significant numbers of people with at least some English ancestry also live in Scotland and Wales, as well as in Ireland, Chile, New Zealand, and South Africa.

Since the 1980s there have been increasingly large numbers of English people, estimated at over 3 million, permanently or semi-permanently living in Spain and France, drawn there by the climate and cheaper house prices.

Culture

Further information: ]The culture of England is sometimes difficult to separate clearly from the culture of the United Kingdom, so influential has English culture been on the cultures of the British Isles and, on the other hand, given the extent to which other cultures have influenced life in England.

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki table code? |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

References

- The CIA World Factbook reports that in the 2001 UK census 92.1% of the UK population were in the White ethnic group, and that 83.6% of this group are in the English ethnic group. The UK Office for National Statistics reports a total population in the UK census of 58,789,194. A quick calculation shows this is equivalent to 45,265,093 people in the English ethnic group; however, this number may not represent a self-defined ethnic group because the 2001 census did not in fact offer "English" as an option under the 'ethnicity' question (the CIA's figure was presumably arrived at by calculating the number of people in England who listed themselves as "white").

- (Ethnic origin) The 2000 US census shows 24,515,138 people claiming English ancestry. According to EuroAmericans.net the greatest population with English origins in a single state was 2,521,355 in California, and the highest percentage was 29.0% in Utah. The American Community Survey 2004 by the US Census Bureau estimates 28,410,295 people claiming some English origin.

- (Ethnic origin) The 2006 Canadian Census gives 1,367,125 respondents stating their ethnic origin as English as a single response, and 5,202,890 including multiple responses, giving a combined total of 6,570,015.

- (Ancestry) The Australian Bureau of Statistics reports 6,358,880 people of English ancestry in the 2001 Census..

- (Ethnic origin) The 2006 New Zealand census reports 44,202 people (based on pre-assigned ethnic categories) stating they belong to the English ethnic group. The 1996 census used a different question to both the 1991 and the 2001 censuses, which had "a tendency for respondents to answer the 1996 question on the basis of ancestry (or descent) rather than 'ethnicity' (or cultural affiliation)" and reported 281,895 people with English origins; See also the figures for 'New Zealand European'.

- "Ethnic minorities feel strong sense of identity with Britain, report reveals" Maxine Frith The Independent 8 January 2004.

- Hussain, Asifa and Millar, William Lockley (2006) Multicultural Nationalism Oxford University Press p149-150

- CONDOR Susan; GIBSON Stephen; ABELL Jackie. (2006) "English identity and ethnic diversity in the context of UK constitutional change" Ethnicities 6:123-158 abstract

- "Asian recruits boost England fan army" by Dennis Campbell, The Guardian 18 June 2006.

- "National Identity and Community in England" (2006) Institute of Governance Briefing No.7.

- Hills, Catherine (2003) "The Origins of the English" p. 18. Duckworth Debates in Archaeology. Duckworth. London. ISBN 0 7156 3191 8

- ^ Krishan Kumar. The Making of English National Identity, Cambridge University Press, 2003

- "Nation", sense 1. The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edtn., 1989'.

- ^ Krishan Kumar, The Rise of English National Identity (Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 262-290.

- English nationalism 'threat to UK', BBC, Sunday, 9 January, 2000

- The English question Handle with care, the Economist 1 November 2007

- English Democrats FAQ

- 'Introduction', The Campaign for an English Parliament

- Andrea Levy, "This is my England", The Guardian, February 19, 2000.

- 'Identity', National Statistics, 21 Feb, 2006

- Sarah Kane, Complete Plays (19**), p. 41.

- "English and Welsh are Races Apart", BBC, 30 June, 2002

- "Found: Migrants with the Mostest", Robert Winnett and Holly Watt, The Sunday Times, 10 June, 2006

- Julie Wheldon. We're all Germans! (and we have been for 1,600 years), The Daily Mail, 19 July 2006

- The BBC article claims a 50-100% "wipeout" of "indigenous British" by Anglo-Saxon "invaders", while the original article (Y Chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration Michael E. Weale et al., in Molecular Biology and Evolution 19 ) claims only a 50-100% "contribution" of "Anglo-Saxons" to the current Central English male population, with samples deriving only from central England; the conclusions of this study have been questioned in Cristian Capelli, et al., A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles Current Biology, 13 (2003). The Times article reports Richard Webber's OriginsInfo database, which does not use the word 'ethnic' and acknowledges that its conclusions are unsafe for many groups; see "Investigating Customers Origins", OriginsInfo.

- Pauline Greenhill, Ethnicity in the Mainstream: Three Studies of English Canadian Culture in Ontario (McGill-Queens, 1994) - page reference needed

- Scotland's Census 2001: Supporting Information (PDF; see p. 43); see also Philip Johnston, "Tory MP leads English protest over census", Daily Telegraph 15 June, 2006.

- 'Developing the Questionnaires', National Statistics Office.

- Krishan Kumar, The Making of English National Identity (Cambridge UP, 2003), pp.1-2.

- A.J.P. Taylor, English History, 1914-1945 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), p. v.

- Norman Davies, The Isles,

- Quoted by Kumar, Making, p.266.

- ^

Simpson, John (1989-03-30). The Oxford English Dictionary: second edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. English. ISBN 0198611862.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - The Black Romans: BBC culture website. Retrieved 21 July 2006.

- The archaeology of black Britain: Channel 4 history website. Retrieved 21 July 2006.

- Gildas, The Ruin of Britain &c. (1899). pp. 4-252. The Ruin of Britain

- celtpn

- Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland before the Romans by Francis Pryor, p. 122. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-712693-X.

- Anglo-Saxon Origins: The Reality of the Myth by Malcolm Todd. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- The Age of Athelstan by Paul Hill (2004), Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2566-8

- Online Etymology Dictionary by Douglas Harper (2001), List of sources used. Retrieved 10 July 2006.

- The Adventure of English, Melvyn Bragg, 2003. Pg 22

- Athelstan (c.895 - 939): Historic Figures: BBC - History. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- The Battle of Brunanburh, 937AD by h2g2, BBC website. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- A. L. Rowse, The Story of Britain, Artus 1979 ISBN 0-297-83311-1

- OED, 2nd edition, s.v. 'English'.

- England — Plantagenet Kings

- BBC - The Resurgence of English 1200 - 1400

- OED, s.v. 'Englishry'.

- Liberation of Ireland: Ireland on the Net Website. Retrieved 23 June 2006.

- A History of Britain: The British Wars 1603-1776 by Simon Schama, BBC Worldwide. ISBN 0-563-53747-7.

- The English, Jeremy Paxman 1998

- EJP looks back on 350 years of history of Jews in the UK: European Jewish Press. Retrieved 21 July 2006.

- Meredith on the Guillet-Thoreau Genealogy

- More Britons applying for Irish passports by Owen Bowcott The Guardian, 13 September 2006. Retrieved 9 January 2006.

- Black Presence, Asian and Black History in Britain, 1500-1850: UK government website. Retrieved 21 July 2006.

- Postwar immigration The National Archives Accessed October 2006

- "Half a million migrants pour into Britain in a year".

- "Record numbers seek new lives abroad".

- "Indians largest group among new immigrants to UK".

- "1,500 migrants enter UK a day".

- Resident population: by ethnic group, 2001: Regional Trends 38, National Statistics.

- Jack Grimston, "Mixed-race Britons to become biggest minority", The Sunday Times, 21 January, 2007.

- An English Parliament...

- Poll shows support for English parliament The Guardian, 16 January 2007

- Fresh call for English Parliament BBC 24 October 2006.

- Welsh nod for English Parliament BBC 20 December 2006

- Scotland's Census 2001: Supporting Information (PDF; see p. 43)

- Scottish Census Results Online Browser, accessed November 16, 2007.

- Key Statistics Report, p. 10.

- Country of Birth: Proportion Born in Wales Falling, National Statistics, 8 January, 2004.

- US Census 2000 data, table PHC-T-43.

- Shifting Identities - statistical data on ethnic identities in the US, American Demographics, December 1, 2001

- Ethnic Origin Statistics Canada

- Staff. Ethnic origins, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories - 20% sample data, Statistics Canada, 2006.

- According to Canada's Ethnocultural Mosaic, 2006 Census, (p.7) "...the presence of the Canadian example has led to an increase in Canadian being reported and has had an impact on the counts of other groups, especially for French, English, Irish and Scottish. People who previously reported these origins in the census had the tendency to now report Canadian."

- Krishnan Kumar - The Making of English Identity

Bibliography

- Expert Links: English Family History and Genealogy Great for tracking down historical inhabitants of England.

- Kate Fox (2004). Watching the English. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0340818867.

- Krishan Kumar (2003). The Making of English National Identity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521777364.

- Jeremy Paxman (1999). The English. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0140267239.

- BBC Nations Articles on England and the English

- The British Isles Information on England

- Mercator's Atlas Map of England ("Anglia") circa 1564.

- Viking blood still flowing; BBC; 3 December 2001.

- UK 2001 Census showing 49,138,831 people from all ethnic groups living in England.

- Tory MP leads English protest over census; The Telegraph; 23 April 2001.

- On St. George's Day, What's Become Of England?; CNSNews.com; 23 April 2001.

- Watching the English – an anthropologist's look at the hidden rules of English behaviour.

- The True-Born Englishman, by Daniel Defoe.

- The Effect of 1066 on the English Language Geoff Boxell

- BBC "English and Welsh are races apart"

- New York Times, When English Eyes Are Smiling Article on the common English and Irish ethnicity

- Y Chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration

- Origins of Britons - Brian Sykes

| England articles | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||||||||

| Politics | |||||||||||||||||

| Culture |

| ||||||||||||||||

| British Isles | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politics |

| ||||||||||||

| Geography |

| ||||||||||||

| History (outline) |

| ||||||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||||||