This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 80.201.153.245 (talk) at 17:51, 16 December 2005. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:51, 16 December 2005 by 80.201.153.245 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Prostate cancer is a disease in which cancer develops in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system. Cancer occurs when cells of the prostate mutate and begin to multiply out of control. These cells may spread (metastasize) from the prostate to other parts of the body, especially the bones and lymph nodes. Prostate cancer can cause pain, difficulty urinating, erectile dysfunction, and other symptoms.

Prostate cancer only occurs in men and develops most frequently in individuals over fifty years old. It is the second most common type of cancer in men and is responsible for more deaths than any cancer except for lung cancer. However, many men who develop prostate cancer never have symptoms, undergo no therapy, and eventually die of other causes. Many factors, including genetics and diet, have been implicated in the development of prostate cancer, but as of 2005, it is not a preventable disease.

Prostate cancer is most often discovered by screening blood tests, such as the PSA (prostate specific antigen) test or by physical examination of the prostate gland by a health care provider. Suspected prostate cancer is typically confirmed by removing a piece of the prostate (biopsy) and examining it under a microscope. Further tests, such as X-rays and bone scans, may be performed to determine whether prostate cancer has spread.

Prostate cancer can be treated with surgery, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, occasionally chemotherapy, or some combination of these. The age and underlying health of the man as well as the extent of spread, appearance under the microscope, and response of the cancer to initial treatment are important in determining the outcome of the disease. Since prostate cancer is a disease of older men, many men will die of other causes before the prostate cancer can spread or cause symptoms. This makes treatment selection difficult.

Medical condition| Prostate cancer | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology, urology |

The prostate

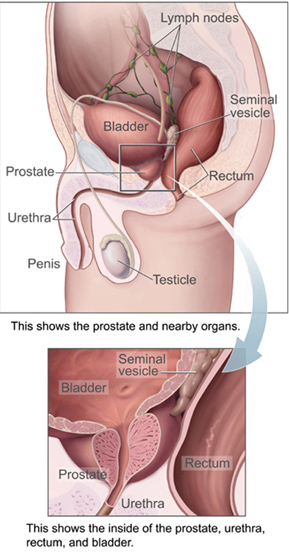

Main article: prostateThe prostate is a male reproductive organ which helps make and store semen. In adult men a typical prostate is about three centimeters long and weighs about twenty grams. It is located in the pelvis, under the urinary bladder and in front of the rectum. The prostate surrounds part of the urethra, the tube that carries urine from the bladder during urination and semen during ejaculation. Because of its location, prostate diseases often affect urination, ejaculation, or defecation. The prostate contains many small glands which make about twenty percent of the fluid comprising semen. In prostate cancer the cells of these prostate glands mutate into cancer cells. The prostate glands require male hormones, known as androgens, to work properly. Androgens include testosterone, which is made in the testes; dehydroepiandrosterone, made in the adrenal glands; and dihydrotestosterone, made in the prostate itself. Androgens are also responsible for secondary sex characteristics such as facial hair and increased muscle mass.

Symptoms

Early prostate cancer usually causes no symptoms. Often it is diagnosed during the workup for an elevated PSA noticed during a routine checkup. Sometimes, however, prostate cancer does cause symptoms, often similar to those of diseases such as benign prostatic hypertrophy. These include frequent urination, increased urination at night, difficulty starting and maintaining a steady stream of urine, blood in the urine, and painful urination. Prostate cancer may also cause problems with sexual function, such as difficulty achieving erection or painful ejaculation. Advanced prostate cancer may cause additional symptoms as the disease spreads to other parts of the body. The most common symptom is bone pain, often in the vertebrae (bones of the spine), pelvis or ribs, from cancer which has spread to these bones. Prostate cancer in the spine can also compress the spinal cord, causing leg weakness, urinary and fecal incontinence.

Pathophysiology

Prostate cancer is an adenocarcinoma, or glandular cancer, that begins when normal semen-secreting prostate gland cells mutate into cancer cells. Initially, small clumps of cancer cells remain confined to otherwise normal prostate glands, a condition known as carcinoma in situ or prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Over time these cancer cells begin to multiply and spread to the surrounding prostate tissue (the stroma) forming a tumor. Eventually, the tumor may grow large enough to invade nearby organs such as the seminal vesicles or the rectum, or the tumor cells may develop the ability to travel in the bloodstream and lymphatic system. Prostate cancer is considered a malignant tumor because it is a mass of cells which can invade other parts of the body. This invasion of other organs is called metastasis. Prostate cancer most commonly metastasizes to the lymph nodes, the rectum, the bladder, and the bones.

Epidemiology

A man's risk of developing prostate cancer is related to his age, genetics, race, diet, lifestyle, medications, and other factors. The primary risk factor is age. Prostate cancer is uncommon in men less than 45, but becomes more common with advancing age. The average age at the time of diagnosis is 70. However, many men never know they have prostate cancer. Autopsy studies of men who died of other causes have found prostate cancer in thirty percent of men in their 50s, and in eighty percent of men in their 70s. In the year 2005 in the United States, there were an estimated 230,000 new cases of prostate cancer and 30,000 deaths due to prostate cancer.

A man's genetic background contributes to his risk of developing prostate cancer. This is suggested by an increased incidence of prostate cancer found in certain racial groups, in identical twins of men with prostate cancer, and in men with certain genes. In the United States, prostate cancer more commonly affects black men than white or Hispanic men, and is also more deadly in black men. Men who have a brother or father with prostate cancer have twice the usual risk of developing prostate cancer. Studies of twins in Scandinavia suggest that forty percent of prostate cancer risk can be explained by inherited factors. However, no single gene is responsible for prostate cancer; many different genes have been implicated. Two genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) that are important risk factors for ovarian cancer and breast cancer in women have also been implicated in prostate cancer.

Dietary amounts of certain foods, vitamins, and minerals can contribute to prostate cancer risk. Higher consumption of animal fat and lower intake of fruits and vegetables both increase prostate cancer risk. These effects are probably related to increased intake of alpha-linoleic acid (found in animal fat) at the expense of linoleic acid (found in vegetable oils). Other dietary factors that may increase prostate cancer risk include lower intake of vitamin E (found in green, leafy vegetables), lycopene (found in tomatoes), omega-3 fatty acids (found in fatty fishes like salmon), and the mineral selenium. Lower blood levels of vitamin D also may increase the risk of developing prostate cancer. This may be linked to lower exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light, since UV light exposure can increase vitamin D in the body.

There are also some links between prostate cancer and medications, medical procedures, and medical conditions. Daily use of anti-inflammatory medicines such as aspirin, ibuprofen, or naproxen may decrease prostate cancer risk. Use of the cholesterol-lowering drugs known as the statins may also decrease prostate cancer risk. Sterilization by vasectomy may increase the risk of prostate cancer, though there are conflicting data. Men who are circumcised may have decreased rates of prostate cancer. More frequent ejaculation also may decrease a man's risk of prostate cancer. One study showed that men who ejaculated five times a week in their 20s had a decreased rate of prostate cancer. Infection or inflammation of the prostate (prostatitis) may increase the chance for prostate cancer. In particular, infection with the sexually transmitted infections chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis seem to increase risk. Finally, obesity and elevated blood levels of testosterone may increase the risk for prostate cancer.

Screening

Main article: Prostate cancer screeningProstate cancer screening is an attempt to find unsuspected cancers. Screening tests may lead to more specific follow-up tests such as a biopsy, where small pieces of the prostate are removed for closer study. As of 2005 prostate cancer screening options include the digital rectal exam and the prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test. Screening for prostate cancer is controversial because it is not clear if the benefits of screening outweigh the risks of follow-up diagnostic tests and cancer treatments.

Prostate cancer is a slow-growing cancer, very common among older men. In fact, most prostate cancers never grow to the point where they cause symptoms, and most men with prostate cancer die of other causes before prostate cancer impacts their lives. The PSA screening test may detect these small cancers that would never become life threatening. Doing the PSA test in these men may lead to overdiagnosis, including additional testing and treatment. Follow-up tests, such as prostate biopsy, may cause pain, bleeding and infection. Prostate cancer treatments may cause urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Therefore, it is essential that the risks and benefits of diagnostic procedures and treatment be carefully considered before PSA screening.

Prostate cancer screening generally begins after age fifty, but may be offered earlier in black men or men with a strong family history of prostate cancer. Although there is no officially recommended cutoff, many health care providers stop monitoring PSA in men who are older than 75 years old because of concern that prostate cancer therapy may do more harm than good as age progresses and life expectancy decreases.

Digital rectal examination

Digital rectal examination (DRE) is a procedure where the examiner inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum to check the size, shape, and texture of the prostate. Areas which are irregular, hard or lumpy need further evaluation, since they may contain cancer. The DRE only evaluates the back of the prostate, but fortunately, 85% of prostate cancers arise in this part of the prostate. Prostate cancer which can be felt on DRE is generally more advanced. The use of DRE has never been shown to prevent prostate cancer deaths when used as the only screening test.

Prostate specific antigen

The PSA test measures the blood level of prostate-specific antigen, a chemical produced by the prostate. PSA levels under 4 ng/mL (nanograms per milliliter) are generally considered normal, while levels over 10 ng/mL are considered abnormal. PSA levels between 4 and 10 ng/mL are considered borderline. However, PSA is not a perfect test. Some men with prostate cancer do not have an elevated PSA, while some men with an elevated PSA do not have prostate cancer.

PSA levels can change for many reasons other than cancer. Two common causes of high PSA levels are enlargement of the prostate (benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH)) and infection in the prostate (prostatitis). PSA levels are lowered in men who use medications used to treat BPH or baldness. These medications, finasteride (marketed as Proscar or Propecia) and dutasteride (marketed as Avodart), may decrease the PSA levels by 50 percent or more.

Several other ways of evaluating the PSA have been developed to avoid the shortcomings of simple PSA screening. The rate of rise of the PSA over time, called the PSA velocity, has been used to evaluate men with borderline PSA levels (between 4 and 10 ng/ml) but, as of 2005, has not proven to be an effective screening test. Comparing the PSA level with the size of the prostate, as measured by ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging, has also been studied. This comparison, called PSA density, is both costly and, as of 2005, has not proven to be an effective screening test. PSA in the blood may either be free or bound to other proteins. Measuring the amount of PSA which is free or bound may provide additional screening information, but as of 2005, questions regarding the usefulness of these measurements limit their widespread use.

Confirming the diagnosis

When a man has symptoms of prostate cancer, or a screening test indicates an increased risk for cancer, more invasive evaluation is offered. The only test which can fully confirm the diagnosis of prostate cancer is a biopsy, the removal of small pieces of the prostate for microscopic examination. However, prior to a biopsy, several other tools may be used to gather more information about the prostate and the urinary tract. Cystoscopy shows the urinary tract from inside the bladder, using a thin, flexible camera tube inserted down the penis. Transrectal ultrasonography creates a picture of the prostate using sound waves from a probe in the rectum.

If cancer is suspected, a biopsy is offered. During a biopsy a urologist obtains tissue samples from the prostate via the rectum. A biopsy gun inserts and removes special hollow-core needles (usually three to six on each side of the prostate) in less than a second. The tissue samples are then examined under a microscope to determine whether cancer cells are present, and to evaluate the microscopic features (or Gleason score) of any cancer found. Prostate biopsies are routinely done on an outpatient basis and rarely require hospitalization. Fifty-five percent of men report discomfort during prostate biopsy.

Staging

Main article: Prostate cancer stagingAn important part of evaluating prostate cancer is determining the stage, or how far the cancer has spread. Knowing the stage helps define prognosis and is useful when selecting therapies. The most common system is the four-stage TNM system (abbreviated from Tumor/Nodes/Metastases). Its components include the size of the tumor, the number of involved lymph nodes, and the presence of any other metastases. The microscopic appearance of the prostate, quantified as the Gleason score, is also incorporated into the staging system. The Whitmore-Jewett stage is another method sometimes used.

The most important distinction made by any staging system is whether or not the cancer is still confined to the prostate. In the TNM system, clinical T1 and T2 cancers are found only in the prostate, while T3 and T4 cancers have spread elsewhere. Several tests can be used to look for evidence of spread. These include computed tomography to evaluate spread within the pelvis, bone scans to look for spread to the bones, and endorectal coil magnetic resonance imaging to closely evaluate the prostatic capsule and the seminal vesicles.

After a prostate biopsy, a pathologist looks at the samples under a microscope. If cancer is present, the pathologist reports the grade of the tumor. The grade tells how much the tumor tissue differs from normal prostate tissue and suggests how fast the tumor is likely to grow. The Gleason system is used to grade prostate tumors from 2 to 10, where a Gleason score of 10 indicates the most abnormalities. The pathologist assigns a number from 1 to 5 for the most common pattern observed under the microscope, then does the same for the second most common pattern. The sum of these two numbers is the Gleason score. Proper grading of the tumor is critical, since the grade of the tumor is one of the major factors used to determine the treatment recommendation.

Treatment

Treatment for prostate cancer may involve watchful waiting, surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, cryosurgery, hormonal therapy, or some combination. Which option is best depends on the stage of the disease, the Gleason score, and the PSA level. Other important factors are the man's age, his general health, and his feelings about potential treatments and their possible side effects. Because all treatments can have significant side effects, such as erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence, treatment discussions often focus on balancing the goals of therapy with the risks of lifestyle alterations.

If the cancer has spread beyond the prostate, treatment options significantly change, so most doctors who treat prostate cancer use a variety of nomograms to predict the probability of spread. Treatment by watchful waiting, radiation therapy, cryosurgery, and surgery are generally offered to men whose cancer remains within the prostate. Hormonal therapy and chemotherapy are often reserved for disease which has spread beyond the prostate. However, there are exceptions: radiation therapy may be used for some advanced tumors, and hormonal therapy is used for some early stage tumors. Cryotherapy, hormonal therapy, and chemotherapy may also be offered if initial treatment fails and the cancer progresses.

Watchful waiting

Watchful waiting, also called "active surveillance," refers to observation and regular monitoring without invasive treatment. Watchful waiting is often used when an early stage, slow-growing prostate cancer is found in an older man. Watchful waiting may also be suggested when the risks of surgery, radiation therapy, or hormonal therapy outweigh the possible benefits. Other treatments can be started if symptoms develop, or if there are signs that the cancer growth is accelerating. Most men who choose watchful waiting for early stage tumors eventually have signs of tumor progression, and they may need to begin treatment within three years. Although men who choose watchful waiting avoid the risks of surgery and radiation, they may also reduce their chances to prevent spread of the cancer. Additional health problems that develop with advancing age during the observation period can also make it harder to undergo surgery and radiation therapy.

Surgery

Surgical removal of the prostate, or prostatectomy, is a common treatment either for early stage prostate cancer, or for cancer which has failed to respond to radiation therapy. The most common type is radical retropubic prostatectomy, when the surgeon removes the prostate through an abdominal incision. Another type is radical perineal prostatectomy, when the surgeon removes the prostate through an incision in the perineum, the skin between the scrotum and anus. Prostatectomy can cure about seventy percent of cases of prostate cancer.

Radical prostatectomy is highly effective for tumors which have not spread beyond the prostate. However, it may cause nerve damage that significantly alters the quality of life of the prostate cancer survivor. The most common serious complications are loss of urinary control and impotence. As many as forty percent of men will be left with some urinary incontinence, usually in the form of leakage when they sneeze, cough or laugh. Impotence is also a common problem. Although penile sensation and the ability to achieve orgasm usually remain intact, erection and ejaculation are often impaired. Medications such as sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis), or vardenafil (Levitra) may restore some degree of potency. In some men with smaller cancers, a more limited "nerve-sparing" technique may help avoid urinary incontinence and impotence.

Radical prostatectomy has traditionally been used alone when the cancer is small. However, courses of hormone therapy prior to surgery may increase cure rates and are currently being studied. Surgery may also be offered when a cancer is not responding to radiation therapy. However, because radiation therapy causes tissue changes, prostatectomy after radiation has a higher risk of complications.

Transurethral resection of the prostate, commonly called a "TURP," is a surgical procedure performed when the tube from the bladder to the penis (urethra) is blocked by prostate enlargement. A small tube (cystoscope) is placed into the penis and the blocking prostate is cut away.

In metastatic disease, where cancer has spread beyond the prostate, removal of the testicles (called orchiectomy) may be done to decrease testosterone levels and control cancer growth. (See hormonal therapy, below).

Radiation therapy

[[Image:brachytherapy.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Brachytherapy for prostate cancer is administered using "seeds," small radioac